Franco’s Hometown Struggles With an Inglorious Past

Fifty years after Francisco Franco’s death, Spain is still reckoning with the legacy of dictatorship. Few places are more iconic of its struggle over identity than Franco’s hometown of Ferrol.

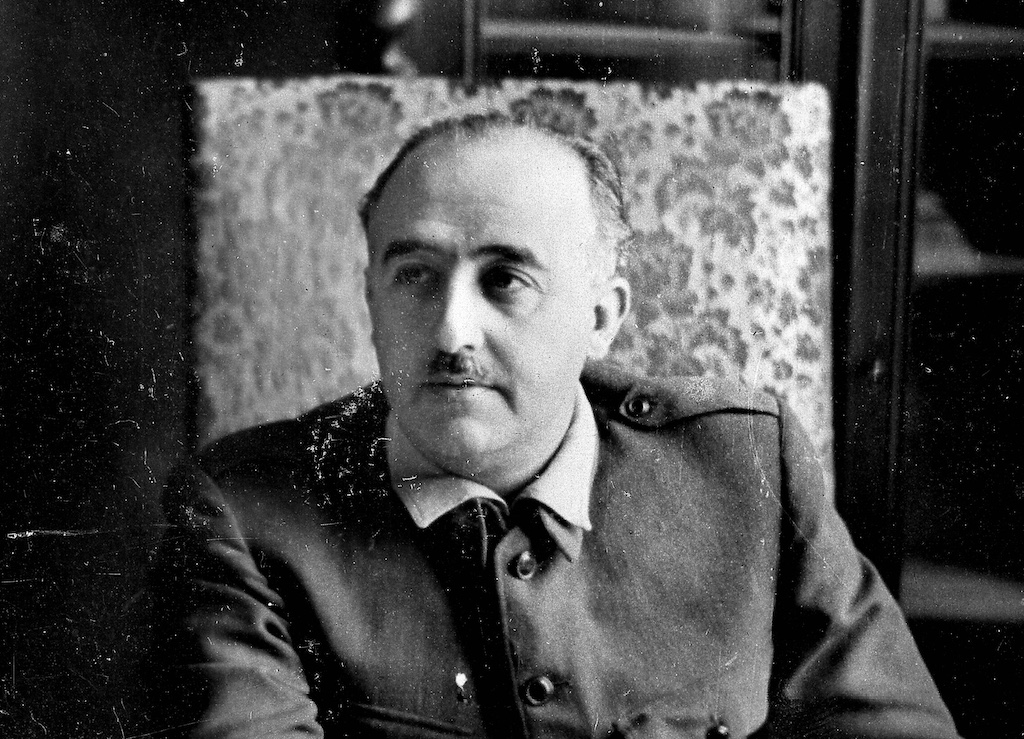

Removing the traces of Francisco Franco from his birthplace of Ferrol could help dispel ingrained prejudices against it. (Roger Viollet / Getty Images)

Fifty years ago, General Francisco Franco died in his bed at El Pardo Palace, outside Madrid, after more than a third of a century ruling Spain with an iron fist. Much has been made of his burial near El Escorial — a symbolic seat of imperial power in Spain’s so-called Golden Age of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries — in the Valley of the Fallen, a mausoleum commissioned by the dictator and built by forced prison labor. But Franco’s birthplace of Ferrol is less iconic, despite its influence on his life from cradle to grave.

The second of five children, Francisco Franco Bahamonde was born on December 4, 1892. Spanish children retaining the surnames of both parents made clear that he was the product of the union between two important naval families. As biographer Giles Tremlett notes: “Such things mattered in Ferrol, which lay at the end of a fourteen-kilometer sea loch of the kind that punctuate the Atlantic seaboard of Galicia, in Spain’s rain-lashed north-west corner.”

With a population of 25,000, most of Ferrol’s inhabitants were reliant on fishing, shipbuilding, or the navy to makes end meet. Francisco’s father, Nicolás, saw active service in the Philippines. In 1898, Spain relinquished the final vestiges of its non-African empire with the loss of Cuba and the Philippines to the United States. The defeat, which prompted a national reckoning with what had gone so wrong since the Golden Age, was highly visible in Ferrol: maimed and injured veterans from the Spanish-American War disembarked, while the local economy and employment took a severe blow when vessels were decommissioned.

Francisco was barely a teenager when he left Ferrol to join the military academy in Toledo. But he was already unequivocal about two basic convictions: trusting politicians inevitably led to betrayal and disaster, and he was destined to pursue a military career in order to reverse Spain’s decline and resuscitate the nation’s former imperial glory. An obsession with duty, routine, and Catholicism was reinforced by his father’s womanizing, which led the paterfamilias to desert his wife and children for a so-called “woman of ill repute” in Madrid.

Following his victory in the Spanish Civil War, General Franco invested time and resources into scripting the semi-autobiographical film Raza (1942, directed by José Luis Sáenz de Heredia) in which an idealized version of his own childhood and family is depicted as a microcosm of Spain. The inclusion of a left-wing brother who betrays the patria and his relatives reflects the divisions within his own family and Ferrol (where the founder of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Pablo Iglesias Posse, was also born, a few decades earlier, in 1850) as well as the tendentious depiction of the civil war as a tragic fratricidal struggle. In reality, the cause of the war was much simpler: an illegal military coup waged against a democratically elected government.

A politically ambitious social climber, General Franco ran his heavily centralist regime from Madrid. Living in a former royal palace, El Pardo, he, his wife, Carmen Polo, and daughter, Carmencita, adopted the trappings of a parvenu royal family. But he never forgot about Ferrol, which was rebaptized “El Ferrol del Caudillo” (the Chieftain’s Ferrol) in his honor. While Easter processions in the city could be traced back to the seventeenth century, the tradition was aggressively promoted in the early years of Francoism, with Ferrol becoming the closest Galician equivalent to Seville and introducing hooded confraternities for the first time.

Over the course of his thirty-six-year dictatorship, 22.5 percent of Franco’s ministers were sons of Madrid — with more coming from Ferrol than Barcelona despite it only having a fraction of its population. This was the consequence of both geographical and military chauvinism. Franco’s family home — comfortable but hardly ostentatious, located near the center but lacking the city’s standout modernist style (more characteristic of Catalonia than Galicia) — bore celebratory plaques and a state-run parador hotel was also opened in the city by the general himself in 1960.

In one of the most impoverished regions of Spain, the Caudillo’s patronage alongside a large military and industrial base ensured that Ferrol was often flush with cash. Members of the Ferrol casino launched a popular subscription to raise funds for a giant equestrian sculpture of Franco, which was inaugurated in the central Plaza de España in 1967, to express their gratitude for services rendered by the dictator in favor of their city and country.

A military hub, Ferrol’s population was augmented by a sizable passing population of male Spaniards stationed there for military service. Even those Spanish citizens who had never ventured onto Galician soil became familiar with images of Ferrol from state-produced newsreels.

Bad Reputation

In the immediate aftermath of Franco’s death, Ferrol became a battleground and a site of pilgrimage for the far right. In this city of contrasts, a strong tradition of fighting for workers’ rights and dignity was also resurrected, with plaques commemorating Franco’s birthplace and his equestrian statue frequently daubed in red graffiti. A combination of losing its chief patron and a rapid process of Thatcher-like deindustrialization — paradoxically carried out by Felipe González’s PSOE government, as Spain sought to become less protectionist in preparation for joining the European Union in 1986 — brought troubled times for Franco’s hometown.

References to Ferrol as “Spain’s Detroit” were hyperbole. Yet it clearly lacked a viable economic model. Because of negative perceptions of the city and Galicia’s infamously bad transportation infrastructure — Ferrol has no working train station and was for a long time only served by secondary roads — its beaches and breathtaking views of the Atlantic rarely enticed local day-trippers or tourists.

Bars and local commerce largely survived off the back of hefty early-retirement packages offered to some locals, but Ferrol was far from the major port it had been during the dictatorship. In population terms, Ferrol is the smallest of Galicia’s seven cities, and it is by far the least visited. Many Galicians have never visited a city that still wrestles with a bad reputation.

Outsiders and the mainstream media still referring to the city with the Francoist monicker of “El Ferrol” was indicative of its fame as a bastion of the reactionary right, and yet the city council during the 1980s and 1990s was often controlled by left-wing parties. In 2002, five years before the passing of the national Law of Historical Memory (banning, among other things, the public commemoration of the dictatorship), the statue dedicated to Franco in Ferrol was removed under the watch of a left-wing Galician nationalist mayor.

Spain was particularly badly hit by the global financial crisis in 2007, with multiple businesses closing in Ferrol and the number of unoccupied properties increasing. A short way up the hill from the harbor and Franco’s birthplace is the working-class district of El Canido. Artist Eduardo Hermida, born and raised in the area, was sufficiently proud of his barrio that he named his daughter, Estrella, after one of its streets. Sensing growing disillusionment over local decline, he launched an initiative in 2008 inviting local artists to paint murals inspired by Diego Velázquez.

The first public subsidy came from local councilmember Yolanda Díaz (a left-winger who currently serves as one of Spain’s deputy prime ministers). The venture grew in stature to the extent that the local brewery, Estrella Galicia, began to provide sponsorship for an annual September festival showcasing the local street art. In 2017, a space was reserved in case Banksy, the world’s most important street artist, wanted to participate. When an image of two members of the Guardia Civil (the rural Spanish police force, originating in the nineteenth century but forever associated with the Franco regime) kissing each other appeared, speculation grew that Banksy had accepted the invitation — until the English artist officially denied authorship or having ever visited Ferrol on his official webpage.

The value of properties in El Canido has risen since the arrival of the street-art initiative, with a new generation of artists and young professionals moving in. Remote working and the rise of other cultural activities, such as a rock festival, have as much to do with this as the street art, but Hermida has undoubtedly returned civic pride to the area and changed some preconceptions about Ferrol in the process.

Franco never wasted an opportunity to pay homage to Spain’s Golden Age, but I can’t envisage him being a fan of Madrid-based artist Sfhir’s mural, drawing inspiration from Diego Velázquez’s portrait (held since 1971 in the Metropolitan Museum in New York) of his slave and fellow painter Juan de Pareja. The street art project in El Canido is not overtly political, but the associated festival clearly attracts a hipper and more progressive crowd than Ferrol’s Easter processions.

Attendees hang out in bars with a different vibe than those in the better-heeled warren of streets around Franco’s birthplace, whose largely middle-aged clientele, unlike the aging drinkers in and around El Pardo, tend not to openly praise the dictator (at least to outsiders such as myself); but they also see no need to remove the celebratory plaques. Franco, for them, forms an important part of local and national history.

Still In Storage

When, as sometimes happens, the Caudillo’s house is vandalized, the Francisco Franco National Foundation (which, remarkably, given the Law of Historical Memory, continues to operate and even has an online giftshop) takes responsibility for cleaning up the mess. The mere existence of said foundation — which has even received public money under democratic rule to fund its activities and was at the forefront of ultimately unsuccessful legal challenges to prevent Franco’s body from being exhumed from the Valley of the Fallen and moved to El Pardo Palace — is an immoral anachronism, with its days numbered.

For any historians passing through Madrid, I would nevertheless recommend visiting its national seat whilst they can. The foundation’s archive — rarely consulted by progressive Spanish historians who, understandably, do not want to pass through its doors — is remarkable. There is correspondence relating to everything from Franco’s quest to find a film director worthy of bringing his autobiographical script onto the screen to confidential reports about Argentina’s General Juan Domingo Perón getting local schoolgirls in Buenos Aires to dress up in his dead wife’s clothes for his sexual pleasure.

Spain, and Ferrol in particular, are thankfully completely different places from when Franco was alive. A parochial brutality forged in his hometown was instrumental to Franco later becoming a world-class tyrant. In 2017, Díaz suggested that Ferrol’s eight-ton Franco statue, which is still held in storage, ought to be melted and reconverted into a homage to the victims of the dictatorship. Such a decision would probably make both ethical and economic sense.

If the emptiness of the restaurants in the parador hotel, intimating the lack of day-trippers outside peak season, is anything to go by, further removing the traces of Franco from the city would perhaps help dispel ingrained prejudices against it. Ferrol remains an idiosyncratic place, but even after the end of its regime-era fame, it reflects many of the contradictions of post-Franco, democratic Spain.