Zohran’s Millionaire Tax Will Raise Revenue

Worries about an exodus of millionaires from New York City are not supported by economics.

New York City Democratic Socialists of America hold a rally in Union Square marking the start of a campaign to tax the rich and win universal childcare, November 16, 2025. (Selcuk Acar / Anadolu via Getty Images)

Ever since Zohran Mamdani began his ascent to mayoral office, journalists and commentators have been debating the effects of his proposed millionaire tax increase. Skeptics worry that the tax will cause large numbers of millionaires to leave New York. Governor Kathy Hochul weighed in back in June, telling one New York news station: “I don’t want to lose any more people to Palm Beach.”

Wealthy out-migration is a concern that demands real engagement. There are three specific concerns that skeptics may have in mind. First, the tax increase might cause so many people to leave that it would paradoxically cause total tax revenue to fall. Second, even if the tax hike does raise revenue, out-migration might mean that it raises substantially less than the Mamdani administration anticipates. And third, out-migration might have other adverse effects on the economy: if millionaires are the ones who “create jobs,” perhaps their departure will have adverse effects on those who remain.

Academic economists have studied all three claims. Unfortunately, the public debate so far has engaged only minimally with existing research. What evidence do we actually have about how millionaires respond to taxes? And what does this evidence mean for Mamdani’s proposal?

The evidence I’ll present below gives some approximate but useful answers that can ground the discussion. If skeptics are truly only worried about the first two concerns, then the academic literature is essentially unanimous: out-migration almost certainly won’t be large enough to fully offset the revenue gains from higher taxes. Under a best guess, out-migration would modestly lower the administration’s revenue forecast: from about $4 billion in increased tax revenue to about $3.95 billion, with a standard estimate of out-migration.

And finally, believing that the tax increase is too high because of the benefits millionaires provide to others requires adopting somewhat fringe views on how strong the trickle-down effect is.

Budgets and Taxes

It’s helpful to start by being clear about how income taxes work. Tax brackets set marginal rates. For a person with $1 million, the income they earn below the first bracket cutoff is taxed at the lowest rate; then the income they earn between the first and second bracket is taxed at the next lowest rate; and so on. When Mamdani proposes increasing the marginal tax rate on millionaires, this means that only the income they earn above $1 million will be subject to this higher rate.

This clarifies a first point: when considering a tax-motivated move between two states, it’s the total (or average) tax that someone pays that matters. For someone with income only slightly above $1 million, the increase in the top marginal rate doesn’t affect their total tax bill that much, because only the income above $1 million is affected.

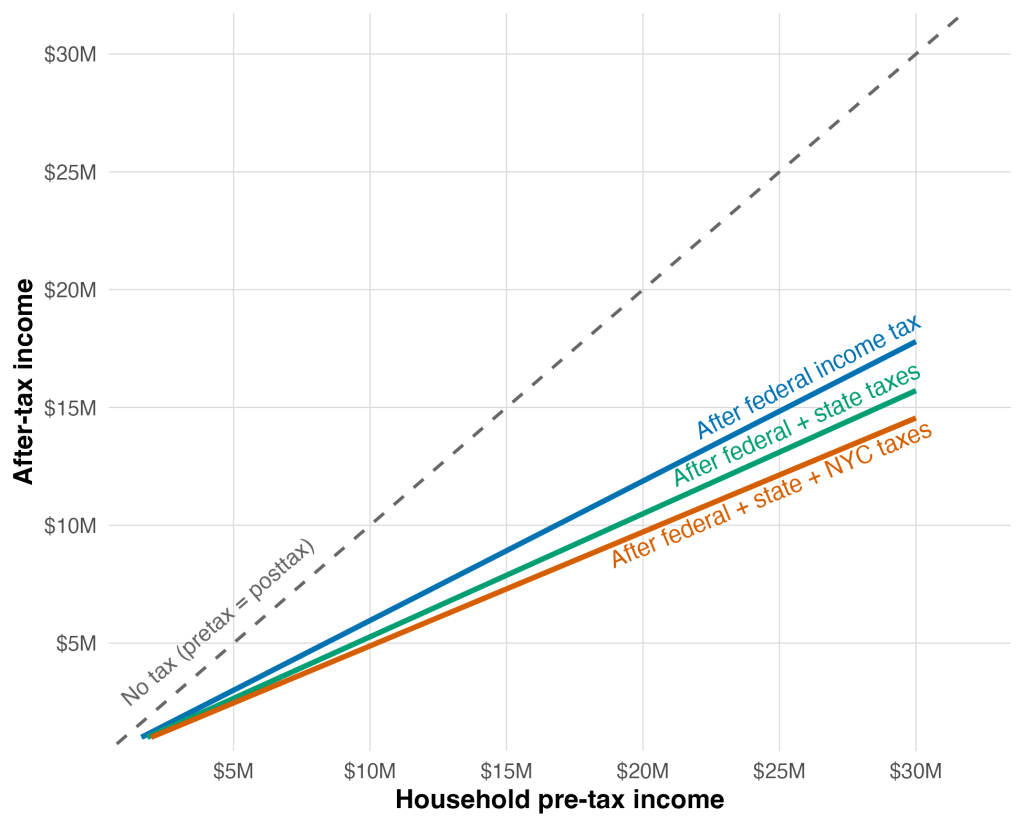

A straightforward way to think about this is to look at a millionaire’s pretax vs. posttax income after applying the full tax schedule. Figure 1, below, does this under the current system, including all deductions, for millionaire married couples with two kids.

Figure 1. Millionaire budgets under the current system

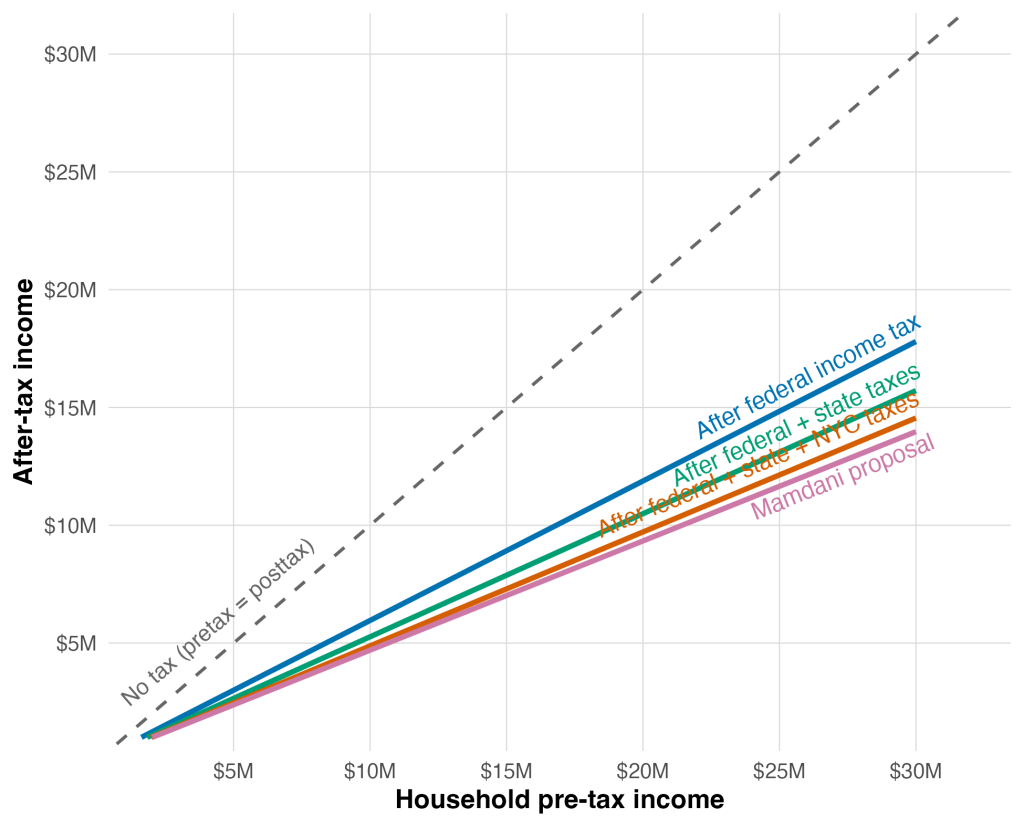

After paying federal, state, and city taxes, a household with $10 million pretax income ends up with about $4.9 million. Mamdani’s proposal would add 2% to the marginal NYC income tax rate for incomes above $1 million, raising it from about 3.9% to 5.9%. This would leave that household with a posttax income of $4.7 million.

After paying federal, state, and city taxes, a household with $10 million pretax income ends up with about $4.9 million. Mamdani’s proposal would add 2% to the marginal NYC income tax rate for incomes above $1 million, raising it from about 3.9% to 5.9%. This would leave that household with a posttax income of $4.7 million.

Overall, Mamdani’s proposal has a relatively small effect on millionaire’s budgets, especially for those with incomes not that far above $1 million, as seen in figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Millionaire budgets under Mamdani’s proposal

For further context, Figure 3 also compares this to the tax system in 1977, the first year for which comprehensive federal and state tax data are available in the tax simulator I use. Top marginal taxes used to be far higher than they are today. In this longer historical context, Mamdani’s proposal appears as a fairly small step toward higher tax rates.

For further context, Figure 3 also compares this to the tax system in 1977, the first year for which comprehensive federal and state tax data are available in the tax simulator I use. Top marginal taxes used to be far higher than they are today. In this longer historical context, Mamdani’s proposal appears as a fairly small step toward higher tax rates.

Figure 3. Millionaire budgets under 1977 tax system

Nonetheless, skeptics’ concerns remain relevant. Some millionaires may indeed be induced to move out of New York City. How many people might this be? What would be the effect on tax revenues? And what would be the effect on others’ jobs and wages? These are not new questions for economists. Looking at existing research can help ground the debate.

Nonetheless, skeptics’ concerns remain relevant. Some millionaires may indeed be induced to move out of New York City. How many people might this be? What would be the effect on tax revenues? And what would be the effect on others’ jobs and wages? These are not new questions for economists. Looking at existing research can help ground the debate.

Tax Elasticities

To measure the extent of tax-induced migration, we can ask a simple question: For a 1% increase in the top marginal tax rate, what percent of millionaires will move out of NYC? The answer to a question like this is called an elasticity, because it’s a measure of how elastic an outcome is. Think of a rubber band — if millionaire migration is more elastic, it means it moves more when we change taxes.

Answering this question isn’t easy, but most academic papers estimate that this elasticity is somewhere between 0 and 1 — and almost certainly no larger than 2. For US state taxes, estimates are usually in the lower end of this range.

The two most relevant papers study wealthy out-migration following top tax increases in other states. In New Jersey, for instance, the marginal tax rate on incomes above $500,000 was increased by two percentage points in 2004 — a change comparable to Mamdani’s proposal ($500,000 in 2004 is about $850,000 today). This kept the top marginal rate in New Jersey below that in NYC at the time, but placed it above the tax rate in New York State and Pennsylvania suburbs.

Comparing households with incomes above vs. below the top marginal rate, a 2011 paper found that the elasticity of out-migration appeared to be no larger than 0.1. That is, for each percent increase in the tax rate, around 0.1% of wealthy New Jersey residents left the state. In 2016 the authors extended the analysis to data covering tax increases in all 50 states — and again found an average elasticity of about 0.1.

Another recent paper studies California, where the top marginal rate was increased by 3 percentage points in 2012. There the authors estimate a migration elasticity of around 0.3 in the years following the tax increase.

And finally, the Fiscal Policy Institute released two reports based on the 2021 tax increase in New York State, in which they find no detectable migration response. Indeed, it’s possible that NYC might have a smaller elasticity than those found in studies of other places. The aggregate elasticity for all of New Jersey or all of California includes people who move from a suburb in one of these states to somewhere in another state. But New York City is unique, and millionaires who have chosen to live there probably didn’t do so because it’s cheap. It seems plausible that they may be even less likely to move out than millionaires in other places. In any case, these existing estimates can serve as useful, and probably conservative, benchmarks.

Most other academic evidence is about migration in Europe, or else focuses on specific populations (patent holders or athletes) whose movements can be tracked without confidential tax data. Nevertheless, it’s worth keeping some of these estimates in mind. The table below summarizes the existing evidence across a range of academic papers.

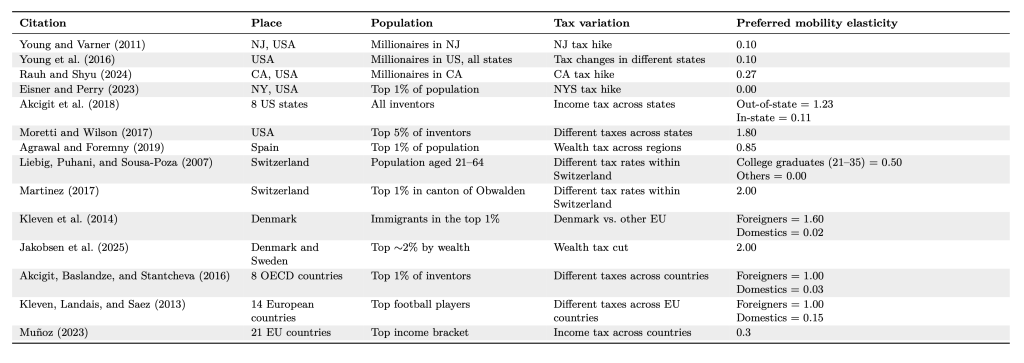

Table 1. Migration-mobility elasticity estimates

In summary, estimates of migration elasticities across US states tend to be below 0.3, which is similar to elasticities for domestic residents in EU countries. The elasticities for foreigners in the EU, as well as for special populations (patent holders and athletes) seem to be between 1 and 2. No study finds an elasticity larger than 2.

Migration and Tax Revenue

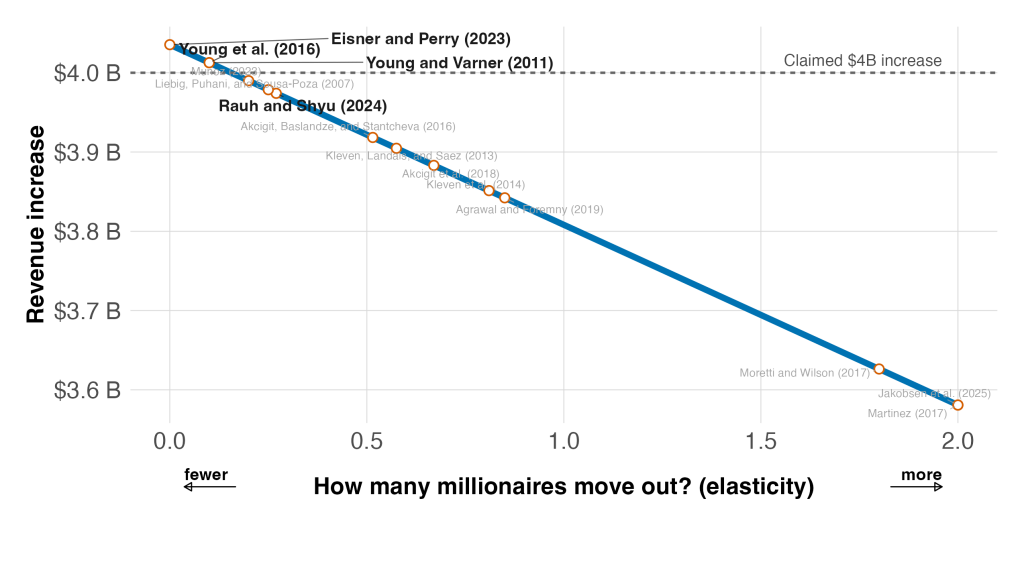

Armed with these estimates, we can begin to approximate the effects of out-migration on tax revenue. For example, using 2021 city-level tax returns, raising the top income tax rate by 2 percentage points mechanically generates approximately $4.03 billion in additional revenue (this is close to the campaign’s reported forecast). If we account for a decrease in the population of millionaires using an elasticity between 0.1 and 0.3, then this falls to somewhere between $4.01 and $3.97 billion. Figure 4 shows this calculation for the full range of elasticity estimates in the academic literature. Under most of the estimates, the decrease is modest; under no estimate is the decrease large enough to fully offset the revenue gain.

Figure 4. Revenue forecasts under different elasticities The academic literature is clear: out-migration can hurt revenue, but current levels of taxation are not high enough for migration to fully counteract the increase in revenue from higher taxes. From a purely revenue perspective, the Mamdani proposal appears rather safe.

The academic literature is clear: out-migration can hurt revenue, but current levels of taxation are not high enough for migration to fully counteract the increase in revenue from higher taxes. From a purely revenue perspective, the Mamdani proposal appears rather safe.

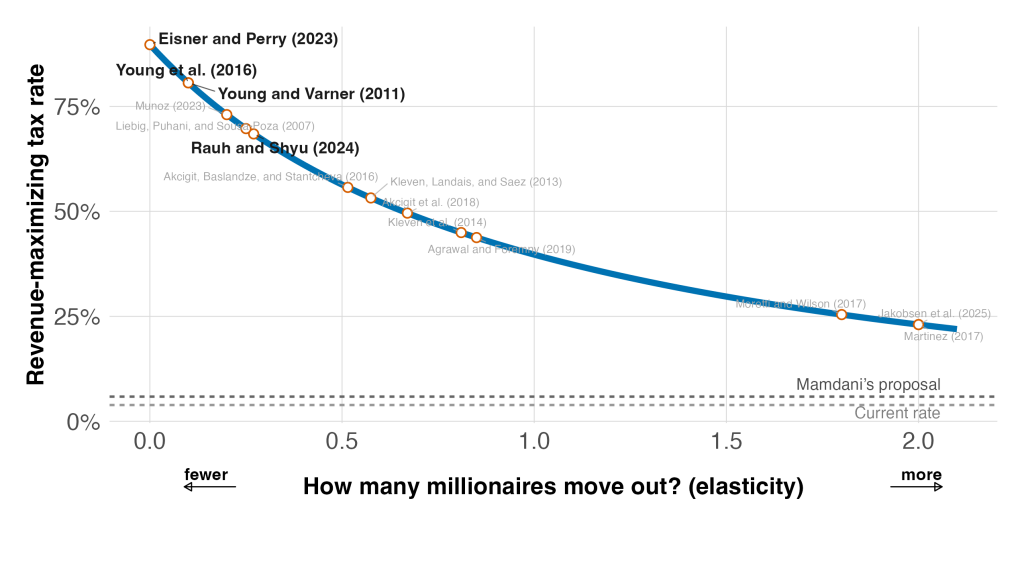

We can ask a further question: Just how much higher could NYC raise its top tax rate before migration would lead to a fall in total revenue? Tax economists have a simple formula they can use to calculate this rate — assuming that, unrealistically of course, millionaire migration is the only thing that would change. Figure 5, below, shows NYC’s revenue-maximizing rate under this assumption, again at different elasticity estimates.

Figure 5. Revenue-maximizing tax rate The key point is that the optimal tax rate depends on our assumptions about how responsive millionaires are to changes in the top marginal tax rate. So if we believe they are not very responsive at all, then the limit is quite high (see top left of figure 5), and if we think they are more responsive, then this would indicate a more cautious approach (see lower right of figure 5). The simple formula claims that, based on observed patterns of out-migration, NYC could raise top marginal income taxes up to 25%, and perhaps as high as 75%, before having to worry about losing revenue. Clearly this doesn’t mean we should do so tomorrow. But it should clarify that lost revenue due to migration is not enough on its own to warrant criticism of Mamdani’s tax proposal. If skeptics are worried about an increase to 5.9%, they must believe that something bad will happen beyond just lost revenue due to migration.

The key point is that the optimal tax rate depends on our assumptions about how responsive millionaires are to changes in the top marginal tax rate. So if we believe they are not very responsive at all, then the limit is quite high (see top left of figure 5), and if we think they are more responsive, then this would indicate a more cautious approach (see lower right of figure 5). The simple formula claims that, based on observed patterns of out-migration, NYC could raise top marginal income taxes up to 25%, and perhaps as high as 75%, before having to worry about losing revenue. Clearly this doesn’t mean we should do so tomorrow. But it should clarify that lost revenue due to migration is not enough on its own to warrant criticism of Mamdani’s tax proposal. If skeptics are worried about an increase to 5.9%, they must believe that something bad will happen beyond just lost revenue due to migration.

Trickle-Down Redux

To justify concern about a 5.9% top marginal income tax rate, skeptics must believe that something else will happen to New York’s economy, beyond lost tax revenue from out-migration. Implicitly or explicitly, they most likely are thinking of some version of trickle-down economics: if millionaires are the ones who create jobs, their departure might hurt New York’s economy.

As before, this concern can be conceptually quantified as an elasticity. The question this time is, for a 1% loss in total millionaire income, what percentage of other workers’ earnings are lost? The answer to this captures the effects of cut wages or job losses as millionaires move out of the city.

Estimating this elasticity is even more difficult. But a couple of recent papers have made some progress. Two papers study a 2013 increase in the top marginal federal income tax rate. One finds that wages in places with more high-income taxpayers fell by at most 0.08% for each 1 point increase in top tax rates.

Another more detailed study looks at wages at the specific firms owned by people subject to the higher tax rate. It finds that wages fell 0.125% for each percent of lower top-bracket income. At the same time, there was no loss of employment at these firms, and the fall in wages occurred only for the highest-paid 30% of workers.

These papers ask how business owners might reduce employee wages in response to paying higher taxes. But since they’re about federal taxes, they don’t speak to the concern that business owners, and their businesses, might leave New York. One paper does address this: it studies wealthy out-migration and its effect on wages and employment in Sweden and Denmark following a wealth tax. It finds an elasticity of bottom earnings to top wealth of about 0.08.

In sum, the estimates above suggest that the trickle-down elasticity may be around 0.1, and probably lies somewhere between 0 and 0.2. It’s also possible that millionaires might have negative effects on others’ wages. For example, if lower taxes encourage business owners to rent-seek and extract more surplus over their workers, this elasticity could in fact be negative. In one paper, Thomas Piketty and coauthors find evidence that CEOs do indeed rent-seek more when faced with lower tax rates.

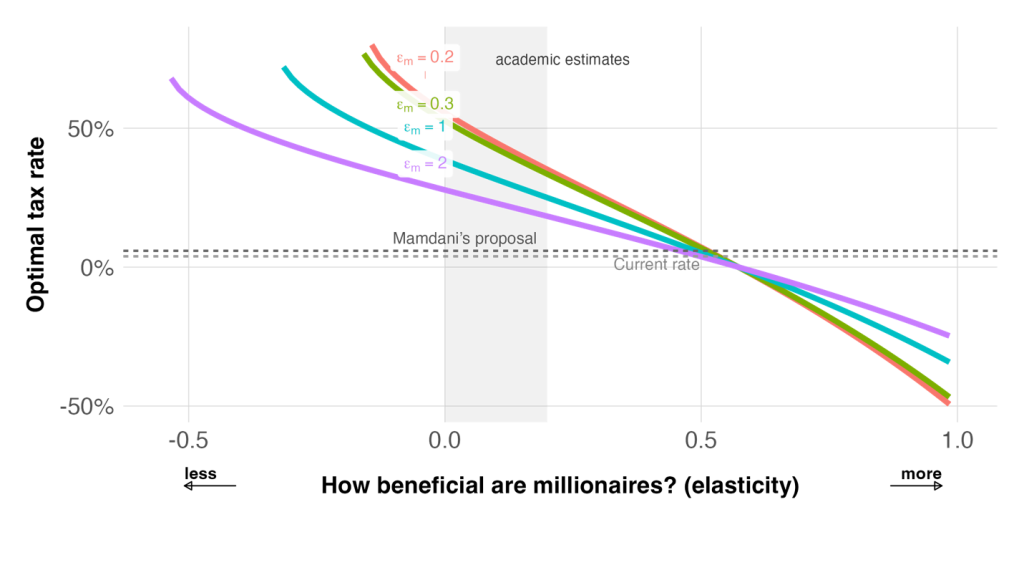

Ultimately, we don’t know exactly how beneficial or harmful millionaires are to the rest of the economy. But we can quantify how beneficial a skeptic must think millionaires are in order to justify concerns about Mamdani’s tax plan. One recent paper extends the simple formula above to account for the fact that millionaires might benefit (or hurt) others’ wages. (It adds this on top of the effects of out-migration and also accounts for the additional concern that higher taxes may induce millionaires to work less hard at their own jobs.) Using this formula, the figure below plots the optimal tax rate across different trickle-down elasticities.

Figure 6. Optimal tax across trickle-down elasticities

If one believes that the trickle-down elasticity is below zero (to the left), they think high millionaire incomes hurt others; as a result, the optimal tax rate is higher. If the elasticity is above zero (further to the right), then millionaire incomes help others. At a certain point, millionaires are so beneficial that it becomes optimal to subsidize them with negative tax rates.

If one believes that the trickle-down elasticity is below zero (to the left), they think high millionaire incomes hurt others; as a result, the optimal tax rate is higher. If the elasticity is above zero (further to the right), then millionaire incomes help others. At a certain point, millionaires are so beneficial that it becomes optimal to subsidize them with negative tax rates.

Each colored line shows the optimal tax rates under different migration elasticities. The red line is when millionaires migrate less (a migration elasticity of 0.2, like the estimates for NJ and CA); the purple line is when they migrate more (an elasticity of 2, like the estimates for migration responses to the Danish and Swedish wealth taxes).

In the graph, when the optimal tax is above Mamdani’s proposal, it means that his proposal is safe and will benefit people relative to the current one; when the optimal tax rate is below it, then the proposal is detrimental.

So in this simplified but useful framework, for Mamdani’s proposal to be too high, the trickle-down elasticity would have to be around 0.5. That is, for every percent of millionaire incomes lost, nonmillionaire wages must fall by half a percent. This is true for all four lines — regardless of how mobile we think NYC millionaires are.

A trickle-down elasticity of 0.5 is four times higher than the largest existing academic estimate. There’s certainly lots of uncertainty in these estimates, and we don’t know how large actual trickle-down elasticities are. But it does seem for now like skeptics are implicitly adopting a somewhat fringe view on just how strong the trickle-down effect must be.

Existing academic research doesn’t provide any sure answers. But it can help ground the debate. Under existing evidence, out-migration alone almost certainly isn’t enough to render Mamdani’s tax increase self-defeating. And for the proposal to be harmful, millionaires must be substantially more beneficial than current evidence suggests.

In sum, existing evidence makes Mamdani’s proposed increase look like a modest and conservative step in the right direction. We should be clear that opponents of the increase are the ones with fringe views.