Francesco Rosi Was a Master of Left-Wing Political Cinema

Italy’s Francesco Rosi produced an unforgettable series of political movies. They feature mob bosses and oil tycoons, corrupt politicians and conspiring spooks, showing how Italian elites used every dirty trick available to exclude the Left from power.

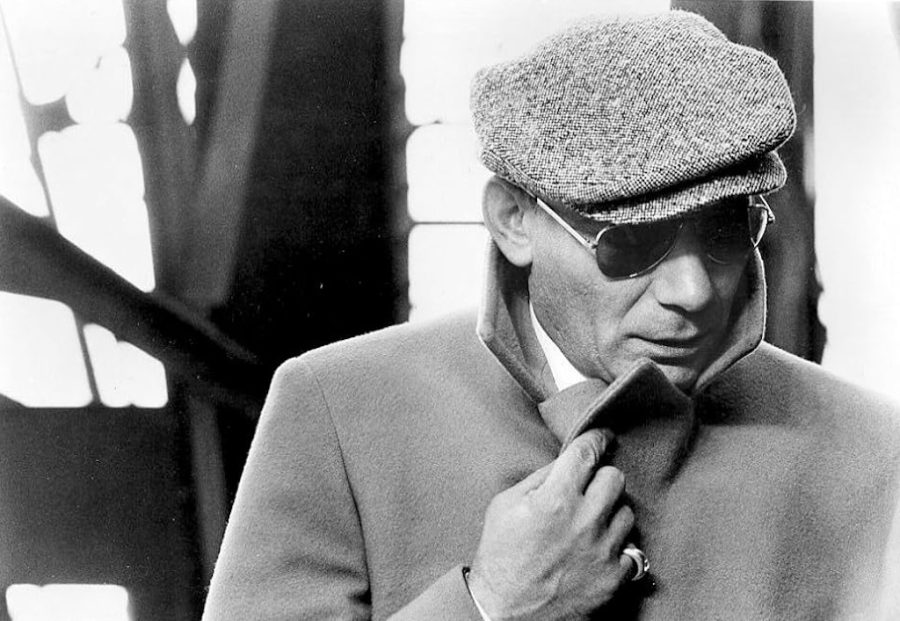

The Italian director Francesco Rosi shot some of the most important political movies ever made. Rosi was interested in a social structure that produces crime because it is itself criminal — and in exposing the legal injustices of the capitalist system. (Charles-André Habib / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

The Italian director Francesco Rosi shot some of the most important political movies of the 1960s and ’70s. Reinterpreting the darkest moments of recent history, he refuted the liberal narratives according to which Italy suffered from the opacity of its economic and political system, compared to the transparency and efficiency of international capitalism.

As a young intellectual, Rosi was interested in a social structure that produces crime because it is itself criminal, not in desperate people who break the rules and thrive, thanks to the fragility of an Italian state that has always struggled to assert itself against the interference of the Catholic Church and the survival of ancient semifeudal powers.

In other words, Rosi sought to draw attention to the legal injustices of the system, in line with the traditional analyses of the Marxist left, mainly represented by the Socialist and Communist Parties. As a (communist) character in one of Rosi’s films puts it: “They always follow the rules. But it’s the rules that don’t work.”

Digging Around the Tree

Born in Naples in 1922, the same year Benito Mussolini marched on Rome, as a young man Rosi had clear ideas. More than by his law studies (which he did not complete), Rosi was shaped by the encounters of his adolescence, when he attended the Liceo Umberto I, the high school of the Neapolitan upper middle class. He became friends with a group of precocious anti-fascists, including the future communist leader Giorgio Napolitano and the journalist Antonio Ghirelli, who also belonged to the Italian Communist Party (PCI). In the last phase of his life, Napolitano held the office of president of the Italian Republic from 2006 to 2015.

Unlike his two friends, Rosi never joined any party, although he was generally considered closer to the Socialists (PSI) than the PCI. From 1962, the PSI ruled the country as a junior coalition partner of the center-right Christian Democrats, but without abandoning its Marxist reference points, including the hammer and sickle as the party’s symbol. As the PSI secretary Pietro Nenni said in March 1961 to justify the future agreement with the Christian Democrats:

Proceeding with the method that peasant wisdom has enshrined in one of the many proverbs of our countryside, when you want to cut down a tree, it is not always useful to use a rope. If you pull too hard, the rope can break. So, it is better to dig around the tree to make it fall. The tree to be felled is, for now, that of conservative and reactionary interests.

It was from this political culture — empirical (and often polemical towards Soviet socialism) but by no means moderate — that Rosi’s cinema drew its lifeblood in his best years, from 1962 to 1976.

Rosi’s filmography consists of sixteen feature films in four decades of activity. What really counts, however, are five films made over a period of fifteen years. Those films defined the unmistakable style that earned him fame and recognition worldwide, with assistance from a trusted team of collaborators: Piero Piccioni for the music, Gianni Di Venanzo and Pasqualino De Santis for the photography, Andrea Crisanti for the set design, and writers Raffaele La Capria and Tonino Guerra for the screenplays.

As often happens in such cases, sometimes Rosi himself fought hard to avoid being reduced to a predefined formula and surprised audiences and critics with projects far removed from his brand as a politically committed director. C’era una volta (“More Than a Miracle,” 1967), which was very loosely based on seventeenth-century Neapolitan fairy tales, clearly falls into this category, as does a film adaptation of Georges Bizet’s opera, Carmen (1984).

Rosi’s five key films reveal such a coherent idea of cinema that, despite the obvious differences between them, they can be considered pieces of a single large mosaic. Winner of the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, Salvatore Giuliano (1962) reconstructs the life and mysterious death of the Sicilian bandit who after World War II was on the payroll of the mafia and the island’s separatists, committed to violently repressing the rural trade union movement, and for some time the undisputed ruler of a small portion of Sicily.

Le mani sulla città (“Hands Over the City,” 1963), awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, denounces the system of political corruption in a Naples held captive by property developers. Il caso Mattei (“The Mattei Affair,” 1972) is an investigation into the president-founder of the public Italian petrochemical group ENI who was killed for opposing the global oligopoly of the so-called Seven Sisters in the oil trade (it won the Cannes Film Festival’s Palme d’Or). The pioneering soundtrack is not only a masterpiece of electronic music but is now considered, with its hypnotic tape loops, a key precursor to techno.

Lucky Luciano (1973) recounts the life of the Italian American mobster who conceived and organized the transatlantic drug trade between New York, Naples, and Sicily. Like Giuliano, he was protected by high-level political figures, in particular the Republican governor of New York and two-time US presidential candidate Thomas Dewey, who granted him a pardon. Finally, Cadaveri eccellenti (“Illustrious Corpses,” 1976), based on a novel by Leonardo Sciascia, is a metaphysical thriller about the essence of power whose plot revolves around the mysterious murder of several judges.

Parallel Investigations

The formula that critics generally used to characterize the first four of these films — cine-inchieste, or “investigative cinema” — works at best as a starting point, because it only captures their most superficial aspects. However, it is easy to understand how this label came to be applied, if one considers the proximity of the films to the events they narrated: about ten years after the deaths of Salvatore Giuliano, Enrico Mattei, and Lucky Luciano, but just a year after the fall of the far-right administration of Naples depicted in Hands Over the City.

Moreover, at the time when Rosi was working, judges had not yet shed light on the many mysteries surrounding the lives and deaths of these figures (in some cases, they never would). For those who saw the films upon release, the impression could only have been that Rosi aspired to replace the magistrates, who in those years were often reluctant to deal with the most politically sensitive cases.

Against this backdrop of judicial acquiescence, Rosi used cinema to present the results (partial and in any case unsatisfactory) of his parallel investigations, but also and perhaps above all to ensure that the biggest scandals of Italy’s postwar republic would not be forgotten. For this purpose, he underscored the inconsistencies in the versions of these stories repeated by traditional media. As a corrupt politician says in Hands Over the City:“We shape public opinion.” Enrico Mattei echoes him nine years later: “People never know anything about what’s behind the facts.”

Similar phrases, referring to the control that big capital exercises over the collective conscience, reappear here and there in his other films of the period. The obsessive presence of newspapers and journalists, television studios, transmitting antennas, screens of all sizes, and numerous press conferences (a real “must” in Rosi’s cinema) serve to remind viewers that news never comes to life on its own: it is constructed and, by definition, partisan.

Rosi was skeptical about the absolute transparency of images. For this reason, in a game of mirrors, he chose to multiply the faces of his main characters in newspapers, on magazine covers, on election posters, on television screens (from The Mattei Affair onward), and even on video surveillance tapes (in Illustrious Corpses).

The same distrust of any naive naturalism is also repeated at the acoustic level. Salvatore Giuliano, for example, never speaks in the film, but his words reach the audience through the testimonies of his men who are questioned at the trial, and through the (probably false) memoirs attributed to him.

In other cases, Rosi makes the process of constructing facts even in the so-called free world explicit by having the characters listen to a previous interview (in The Mattei Affair) or reread a statement recorded in the first part of the same interrogation (in Lucky Luciano), in a procedure probably reminiscent of Samuel Beckett’s 1958 play Krapp’s Last Tape. In an information system corrupted by the interests of the most powerful, where the word “truth” should only be written in quotation marks, Rosi’s cinema becomes a sort of counterpower, indispensable to the proper functioning of democracy itself.

Welles and Rosi

Orson Welles is an artist not usually mentioned in connection with Rosi, but they share a number of similarities, visual, thematic, and narrative. Consider the main elements of Citizen Kane: a great character at the center of the scene, the omnipresence of the media, the flashback investigation, the narrative circularity, the dizzying chronological leaps, the sense of destiny and the inevitability of defeat, the inability of the journalists to solve the enigma, the oppressive atmosphere. It all points to Welles serving as a model for Rosi, whether conscious or unconscious.

However, where Rosi breaks from Citizen Kane is in the ending. Welles was not at all satisfied with the famous “Rosebud” idea, but he accepted that the audience had paid for their tickets and were entitled to an answer. “It was the only way we could find to get off, as they used to say in vaudeville,” he commented in a famous interview with Peter Bogdanovich.

Perhaps we could say that Rosi follows the model of Citizen Kane, including its disappointing conclusion (for the journalists), without giving viewers the compensation of the tracking shot that closes the film with a revealing inscription. For Rosi, the investigation must fail because, if it did not, the film would lie, betraying the political function that he assigns to his cinema.

If it were enough to fight the bad apples one by one, it would be fair to shoot traditional detective stories. In Rosi’s films, judicial failure is never a true failure, because the very notion of guilt has changed. Punishing those responsible for a crime is right. But there are crimes for which individual convictions cannot be achieved unless we turn a blind eye to the system that produced them and become complicit in it.

Waiting for the Right Moment

Films of this kind obviously require a special work method, which Rosi refined over the years. It involved copious reading, meticulous consultation of judicial investigation records, and interviews with as many direct witnesses as possible (often redoing the work of the police, which was not always reliable).

Rosi assembled collections of photographs and newspaper clippings and conducted a great deal of field research among ordinary people, spending long periods — before, during, and after filming — in the places where the events had taken place, to let the spaces and the architecture “speak.” The truth without quotation marks can be found in every detail, and Rosi often recounted how the key to a scene was unintentionally suggested to him by an unforeseen exchange with an extra.

Once moviemaking is conceived in this way, the moment of shooting becomes little more than the apex of a documentation process that could last for years and at any moment risked getting bogged down for a variety of reasons (political obstacles, lack of funds, logistical issues, etc.). In fact, Rosi’s projects often failed to materialize. This was the case, for example, with a film about Che Guevara that worked on for almost a year (with Fidel Castro’s approval) after Guevara’s assassination in Bolivia.

In other cases, fortunately, things went better for Rosi, even if, sometimes, this meant waiting patiently for the right moment. For example, the first seeds of the film about Salvatore Giuliano were sown during a visit to Sicily years earlier, when everyone in Palermo was talking about the armed exploits of the secessionists and Rosi immediately sensed the subject’s potential. However, the opportunity to make the movie would only come much later, after he had made a name for himself.

Reflecting on Power

Salvatore Giuliano, the film that brought Rosi international acclaim, has little in common with a standard mafia movie, even though it is considered a forerunner of the genre and Martin Scorsese has repeatedly cited it as one of the films that most inspired him. Salvatore Giuliano is, to all intents and purposes, a film about recent Italian history, which finds its political and emotional center of gravity in the Portella della Ginestra massacre of May 1, 1947.

On that day, Giuliano’s men fired on a peaceful peasant demonstration, killing eleven and injuring many, with the aim of intimidating the socialist movement ahead of the elections scheduled for the following year. Giuliano’s closest collaborator, Gaspare Pisciotta, who would die of poisoning in prison, named the Christian Democrat politician Bernardo Mattarella, father of the current president of the Italian Republic, as one of the masterminds behind the massacre.

Salvatore Giuliano would establish some of the cornerstones of Rosi’s political cinema for the years to come. First of all, in order to reveal hierarchies and power relations, Rosi needs great characters, capable of situating themselves smack in the center of the web and of capturing the audience’s attention. In short, ensemble acting must be accompanied by the continuous presence of an exceptional soloist, who must in turn be played by a talented actor.

Rosi is interested above all in the context, as he never ceased to declare (for example: “I did not want to make a biography of Lucky Luciano. Under the pretext of Luciano’s character, I dealt with the mafia, trying especially to keep reflecting on power, as I had begun doing with Salvatore Giuliano”). At the same time, however, in order to bring to life a world populated by dozens of supporting characters, a strong gravitational center is indispensable.

In Rosi’s films, this almost inevitably ends up being larger-than-life heroes whose magnetism enables them to dominate everything around them. Ordinary individuals (and characters) would never be able to animate such a large crowd on their own, but Rosi’s super-characters can, and the director has to valorize them as much as possible.

Pieces of the Puzzle

The case of Salvatore Giuliano is quite unusual because the bandit is constantly on the scene but remains a sort of missing piece of the puzzle. Rosi almost always frames him from a distance (so much so that he is only recognizable by his white raincoat), never lets him speak, and only shows him at length when he is dead, as a corpse, in order to remind viewers that his story — including his murder — remains shrouded in mystery.

From Hands Over the City onward, however, Rosi turns to first-class showmen: the extraordinary Rod Steiger in the role of property developer Eduardo Nottola, Gian Maria Volonté for Enrico Mattei and Lucky Luciano, and the enigmatic Lino Ventura in Illustrious Corpses. All these actors are capable of carrying the film on their own, thanks to their charisma, even if Hands Over the City and Lucky Luciano are more traditional in staging a conflict between good and evil and in giving space to those who oppose the criminal system.

This is perhaps why Lucky Luciano is the least convincing of Rosi’s investigative films, although Rosi’s choice to shoot a sort of anti-Godfather is to be admired. In contrast with Francis Ford Coppola’s depiction of Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian mafia is deliberately stripped of all ethnic stereotypes and represented as a cold and ruthless business, without colorful rituals and false codes of honor.

Significantly, Salvatore Giuliano’s invisibility contrasts with the omnipresence of Rosi’s other protagonists in a wide variety of media, from the election posters of Nottola in Hands Over the City to the multiplication of Enrico Mattei’s image across dozens of black and white videos, as if men with such hypertrophic egos could not help but occupy all the space around them, and in all possible formats.

From a purely visual standpoint, in addition to filming them from below to make their figures more imposing, in Rosi’s cinema, the gigantism of the characters translates into their ambition to climb higher and higher — not just metaphorically. As a Marxist who was attentive to power relations, Rosi always sought to convey the visible and invisible hierarchies of our society through memorable images. For this reason, he soon identified the helicopter (filmed from below) as the true icon of his time: the triumphal chariot through which capitalism’s victors dominate space and descend from the sky to impose their will on ordinary mortals.

While Salvatore Giuliano limits himself to taking refuge in the mountains, where the Italian army cannot reach him and from where he keeps those below him in check, in the case of the builder Nottola, with his modern ten- or fifteen-story buildings, the urge to defy gravity is particularly evident. The same can be said for Mattei’s pharaonic constructions (the colossal oil wells) and his obsession with flight.

Only in the case of Lucky Luciano does this relationship remain more nuanced and ambiguous. New York, the city he loves and that made him what he is, looks like a forest of skyscrapers seen from the harbor. His return to Italy in 1946, when he was pardoned on condition that he leave the United States, is represented by Rosi through a cross-cut montage in which an imposing Statue of Liberty is transformed into an equally imposing cross in a small southern town. From the modern power of capital to the atavistic power of religion.

Necessary Villains

Another fundamental trait of Rosi’s filmography is his predilection for negative characters. Occasionally there are positive figures who try to set things right, but even in these cases the director’s empathy is reserved for the villain. Rosi obviously roots for his defeat, yet it is to him that the movie grants the few existing moments of true psychological introspection.

There is certainly a special relationship between the will to power, boundless ego, and an aversion to any form of rule, including laws. Today, a filmmaker like Rosi would without doubt have an eye for what is happening in Silicon Valley. However, the chief reason for his interest in the criminals is probably political.

Whether they are gangsters or real estate developers, villains are better than good guys for showing how the system works. Compared to those who follow the rules, they have no regard for legal formalities: they live in a world of power relations that are perfectly transparent in their brutality, and this makes them perfect for exposing the hypocrisies of capitalist society.

Gangsters, for example, know that they perform a “necessary” task, providing a range of services that are prohibited by law but nevertheless sought by large sections of the population. According to the logic of the free-market economy, that need (drugs, alcohol, prostitution, gambling) must be satisfied.

This is the argument that leads Lucky Luciano to say: “People wanted to drink. And someone had to bring them something to drink. Otherwise, others would have done it, like the government did . . . We performed a social function.” But the same applies to deputies, senators, and governors: “They used us to cover their muck. The politicians never had any trouble in maneuvering with racketeers and mafiosi.”

Rosi is primarily interested in outlaws for what they allow us to see. The arguments criminals use to absolve themselves are clearly ridiculous, but their analyses of the structural injustice of the system surpass those of any political scientist in Chicago or Harvard in terms of lucidity. Men like Lucky Luciano learned from the streets, but the streets taught them well. They do not let themselves be fooled. From this point of view at least, their skepticism toward rules has a lot to teach ordinary citizens.

This is the lesson of Bertolt Brecht, the true hero of leftist Italian intellectuals in those years. Lucky Luciano is a gifted orator in his irresistible Italian American dialect, but the taciturn Salvatore Giuliano and Edoardo Nottola are no less the heirs of Macheath, the crook in theThreepenny Opera who declares from the gallows, in a now-famous passage: “What is a picklock to a bank share? What is the burgling of a bank to the founding of a bank? What is the murder of a man to the employment of a man?”

A Political Tragedy

Compared to Rosi’s other investigative films, The Mattei Affair is somewhat of an exception in terms of character development. A partisan commander during the Resistance, champion of state-owned enterprises, enemy of the international oil monopoly, fervent supporter of anti-colonial movements around the world, and a figure in constant conflict with the pro-business politicians of his own party (the Christian Democrats), Mattei had all the characteristics to appeal to Rosi.

However, there is also another Mattei, whom Rosi does not hesitate to show us: the leader of an economic empire unprecedented in Italian history, the cynical manipulator of public opinion through ENI-owned newspapers, the secret financier of politicians and parties (ready to make deals even with the neofascists, if necessary). His was a concentration of power that led many to see him as a potential threat to Italian democracy. Or, as a Time magazine journalist summed it up, simply “the most powerful Italian since Julius Caesar.”

Mattei’s exceptionality is perfectly portrayed by Gian Maria Volonté: a dictator-seducer who, in one of the film’s most impressive scenes, practically kidnaps a liberal economic journalist (played by the communist playwright and theatre director Luigi Squarzina) who has attacked him, forcing him to visit the many ENI facilities scattered around the world, from El Borma in Tunisia to Abadan in Iran. On their journey, words and images reinforce each other in a powerful anti-colonialist message that is still relevant today (as Mattei remarks at one point, the time has come to “consider the Third World a world of men, not of inferior beings”).

Mattei’s superhuman stature emerges mainly from the prodigious control he exercises over the natural elements that docilely bend to his will: the earth (pierced by his drills), the water (thanks to the oil wells in the sea), the air (through constant travel by plane and helicopter), and then fire (the flames of the wells at night, which allude to the explosion of the aircraft in which Mattei was killed).

Mattei does not embody the traditional hero of so many films with a message: he is not a “good guy,” and, indeed, as a journalist says in the movie the day after his death: “Had he succeeded, he would have screwed up democracy in Italy.” However, viewers easily realize that, for all of Mattei’s dark sides, Rosi not only considers his death a true political tragedy but also ends up identifying with him — something that obviously does not happen with Salvatore Giuliano, Edoardo Nottola, or Lucky Luciano.

As a champion of Italy’s state-owned industry against the international trusts, Mattei ideally represents a sort of “double” of the Cinecittà director who struggles against the Hollywood majors in the name of an alternative idea of cinema. Their battles take place in different fields, but they are at least partly the same. Rosi uses their objective closeness to shed light on aspects of Mattei’s project in a way that would not have been possible from a more detached position.

The film thus presents the president of ENI as a missed opportunity, the symbol of a brief interlude in which it seemed that small powers such as Italy and the Third World countries fighting the old colonial players could finally make their voices heard. At the same time, one gets the impression that Rosi would not have been able to portray Mattei so well if he had not also brought out his gangster-like ruthlessness.

Catacombs of Power

Compared to Rosi’s previous films, Illustrious Corpses marks a change, immediately noted by critics. First of all, the film is based on a novel and, at least on the surface, follows the structure of a traditional detective story, with a principled police officer investigating a series of crimes, played by a specialist in this role, the French-Italian actor Lino Ventura. What remains of Sciascia’s (weak) book is the basic plot: a story of political assassinations targeting judges in a country on the road to military coup, where everyone is equally responsible, including the communist opposition, secretly affiliated with the power it claims to want to overthrow.

Rosi, however, makes a significant change to the story. In the book, the policeman and the secretary of the Communist Party are found murdered, and the reader is led to suspect that the former, before committing suicide, killed the latter after realizing that he too was involved in the plot. In the film, on the other hand, we see them both succumb to the shots of an invisible sniper (not too differently from the massacre of Portella della Ginestra).

From the very first scene, set in the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo, among dozens of embalmed bodies according to an ancient practice that was discontinued only in the nineteenth century for health reasons, Illustrious Corpses surprises viewers with Andrea Crisanti’s oppressive, anti-naturalistic sets. They evoke a world in which the aspirations of Salvatore Giuliano, Eduardo Nottola, Lucky Luciano, and Enrico Mattei have been realized but have also revealed their most frightening side.

The action takes place in disproportionate settings (somewhat like in German expressionist cinema), magnified by telephoto lenses combined with a wide angle. Whether it is the barracks that have devastated the suburbs of Agrigento, the half-empty corridors and staircases of the Archaeological Museum of Naples, or the headquarters of the PCI, it is clearly an unlivable world, where no one feels at ease. A true waking nightmare: exactly what Sciascia’s book, with its eighteenth-century lightness, does not even come close to being.

When the film was released, many saw Illustrious Corpses as an even more profound break with Rosi’s cinema than the deliberately light-hearted More Than a Miracle. Fifty years later, it makes a different impression: not so much a turning point in Rosi’s filmography, but, rather, the one movie that better than any other allows viewers to appreciate certain aspects that were present in his cinema from the start.

Rosi was consistently rather cold towards modernism. In an interview with the French Marxist critic Michel Ciment, he made the following remark: “Since I don’t give a damn about modernism, but I believe in the things of modernity, I make my own films, and, if these films happen to have modern content in a modern form, so much the better.”

However, it is difficult to deny the proximity of Rosi’s films to the most complex and self-aware fiction of the 1960s. Traditional police investigations are reassuring, because the crime is followed by the hunt for the culprit and — after a long pursuit — his identification and punishment. But in Rosi’s cinema, nothing of the sort happens. The more the investigation evolves, the more the mystery becomes dense and impenetrable.

One of the characteristics of postwar Italian cinema is the debt owed by all its protagonists to neorealism and, at the same time, even in the leading filmmakers, the presence of elements that do not correspond to it. It is as if it were only through friction with different ingredients that this tradition reaches its fullest potential, avoiding the mere photographic recording of life or social pedagogy.

In Roberto Rossellini, religion and a sense of the miraculous played this role. In Luchino Visconti, it was opera and melodrama. In Vittorio De Sica, the great Neapolitan theatrical tradition. In Federico Fellini, the circus and the dreamlike dimension (often linked to memory). In Pier Paolo Pasolini, a passion for bodies. In Michelangelo Antonioni, modern painting (from Giorgio Morandi to Mark Rothko).

In Rosi’s case, the most obvious candidate for this essential contrasting role would be militant politics. Illustrious Corpses, however, invites viewers to note that even Rosi’s previous films, apparently so closely linked to the neorealist creed (a creed from which the very idea of investigative cinema derives), were marked by the same poetics of excess and abnormality that finally found full expression here thanks to the encounter with Sciascia.

The Unofficial Version

Rosi became increasingly pessimistic over time. While Hands Over the City gave ample space to the communist city councillor who at the end of the movie announces that “things are changing,” an almost opposite moral concludes Lucky Luciano, where the fight against crime has turned into a sterile competition between political factions. From this point of view, Illustrious Corpses would be the final stage of a growing disillusionment with the possibility of change.

Yet even in this case, it should be remembered that the same feeling of inevitability runs through all of Rosi’s films from the start of his career: the tragic conviction that individuals always lose out to the system. It is the romantic-existentialist side of his Marxism. The circular constructions of most of his major films and the fact that two of them — Salvatore Giuliano and The Mattei Affair — start from the death of the protagonist, just like a film noir, further reinforces the sense of inevitability.

In this regard, too, there is a clear evolution over time, as if Rosi had only gradually become fully aware of the potential of the mechanism he had fabricated. In none of his films is the invitation to break the fourth wall as evident as in The Mattei Affair, where at a certain point the investigation recounted intersects with that conducted by the director himself while he was preparing the movie.

In researching the death of the ENI president, Rosi turned to Mauro de Mauro, a highly talented investigative journalist with expertise in Sicilian organized crime but with a controversial past, to help him reconstruct Mattei’s last days in Sicily. While following a lead, on September 16, 1970, De Mauro was kidnapped by unknown persons, and nothing more was heard of him. Decades later, the judiciary established that it was most likely the Mafia that had killed him to stop him from revealing what he had discovered about Mattei’s death — at the time, the official version was that it had been a simple plane crash.

De Mauro’s disappearance gave Rosi the opportunity to include his story and the making of the film in the movie itself. He played himself in a couple of scenes, in a continuous exchange between reality and cinema, mere suppositions and suspicions too disturbing to be proven. A way of reminding viewers that no one is safe, and that the world of the silver nitrate is extraordinarily close to our own.

However, it is Illustrious Corpses that takes this reasoning to its extreme conclusion. In the finale, to prevent the military from exploiting popular outrage over the killing of the PCI secretary to launch their coup, the communists decide to endorse the official story that investigator Rogas shot him in a fit of madness: even if they know that this is a reversal of the maxim attributed to Antonio Gramsci that “truth is revolutionary.”

The scene is preceded by a series of images designed specifically to instill terror in viewers, in an Italy where left-wing political militants (socialists, communists, young activists) had grown accustomed to sleeping away from home several nights a week for fear of a military takeover. Here, archival footage of recent demonstrations is deliberately intercut with (fictional) footage of soldiers waiting patiently in their armored vehicles.

In a climate of fear about the very survival of Italian democracy, the end of the film is set in the exact present or close future, implicitly asking the audience to take sides with regard to the current crisis and accusing the PCI of excessive caution. In short, the conclusion rests in the hands of the viewers, who, as citizens, will have the final say.

Committed Art

Rosi’s slow artistic decline, which began immediately after Illustrious Corpses, has much to teach us about his masterpieces, too. Between 1978 and 1997, he managed to shoot six more films, all adaptations.

Regarding these films, it is easy to speak of a sudden exhaustion of Rosi’s creative vein (the adaptation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold was particularly unsuccessful, suffering from, among other things, the removal of the novel’s political theme). Or one could, just as legitimately, attribute his difficulties as a director to the more general crisis in Italian cinema production after the American studios abandoned Cinecittà.

Another interpretation is also possible. Precisely because his cinema was built around an empty center, from the outset, Rosi looked at the political and social forces that were called upon to fill that void, ideally passing the baton to the audience. From the late 1970s, however, this mechanism broke down.

In 1979’s Cristo si è fermato a Eboli (“Christ Stopped At Eboli”), set in the 1930s, we witness a sudden retreat into the past, which in subsequent films will be repeated in a variety of ways, as if Rosi could only evoke a time that was definitively lost. In one form or another, in Rosi’s final works, regret for yesterday and elegy for the past ultimately prevail over everything else.

Even more than his capacity to observe the present, what the late Rosi lost was his ability to look ahead, as he had always done before. Of course, one cannot help but wonder how much this retreat was influenced by the new political climate and the loss of interlocutors in the hedonistic and vulgar Italy of the 1980s. Certainly, with the driving force of the long 1968 movement exhausted, fewer and fewer Italians were able to imagine an alternative future.

In this context, Rosi seems to have suffered the special curse that weighs on all cinema that has its roots in neorealism, when the high passion of creation subsides, the torment of the new diminishes, and the calm of timeless repetition prevails. Just as Roberto Rossellini’s films fall into didacticism and historical pedagogy as soon as reality ceases to vibrate with the secret strings of miracle, so Rosi’s cinema lapses into inert calligraphy just when, all around him, faith in the secular miracle that is the collective hope in revolution, dissolves into thin air.

Fortunately, Rosi’s masterpieces are still here. And, almost half a century after Illustrious Corpses, they remind us what great committed art can do when it is truly art.