Heated Rivalry and Modest Fantasies for Monstrous Times

An obscure 19th-century Russian novel about love and class and a 21st-century gay hockey romance might seem worlds apart. But both Heated Rivalry and Molotov offer the same thing: small parables of tenderness and bravery in overwhelming times.

At their most modest, happy-ending romance stories like Heated Rivalry soothe troubled minds amid social turmoil. At their most radical, they expand who gets to imagine themselves living well in an unjust society. (Accent Aigu Entertainment / Bell Media)

The appeal of the Canadian gay hockey romance show Heated Rivalry isn’t hard to understand. Its young stars are beautiful and appealing, and their romance is sexy and sweet. But perhaps most appealing of all, in this era of performative cruelty, it is a television show in which the central characters’ fears — that if they reveal their true feelings they will be romantically rejected, and that if their homosexual love affair is discovered they will be disowned and ruined — are ultimately unfounded. We wait the entire show for the other shoe to drop, and this anxiety lends the romance a special charge, but ultimately nothing bad happens at all.

The world of Heated Rivalry is just a little bit better than the one that exists, but entirely imaginable from where we currently stand. The way to get there appears easy. A few people just have to be decent to each other, to carve out space to live well within the structures and institutions that exist. It’s nothing revolutionary, but the show has been devoured with an urgency that suggests this image of an ever-so-slightly better reality was sorely needed.

Romance is a genre built on fantasy, of course. But there’s something poignant and telling about Heated Rivalry’s breakout popularity cresting against the backdrop of US imperial aggression, domestic authoritarianism, and disturbing revelations about private abuses of power among the political and financial elite. Perhaps this vision of kind and handsome boys in love is helping viewers cope with a degraded present — inviting them into an alternative world where the biggest problems can be overcome through personal bravery and interpersonal tenderness.

If so, it wouldn’t be the first popular romance to fulfill this social role. One hundred and fifty years ago, in the Russian Empire, an obscure novel served much the same purpose for its readers. Small fantasies of decency and love, it turns out, often serve a political function. At their most modest, they can soothe our troubled minds with surmountable challenges and happy endings. At their most radical, they can expand the boundaries of who gets to imagine themselves living well in a society ruthlessly determined to hoard the spoils of the good life for a privileged few.

The Story of Molotov

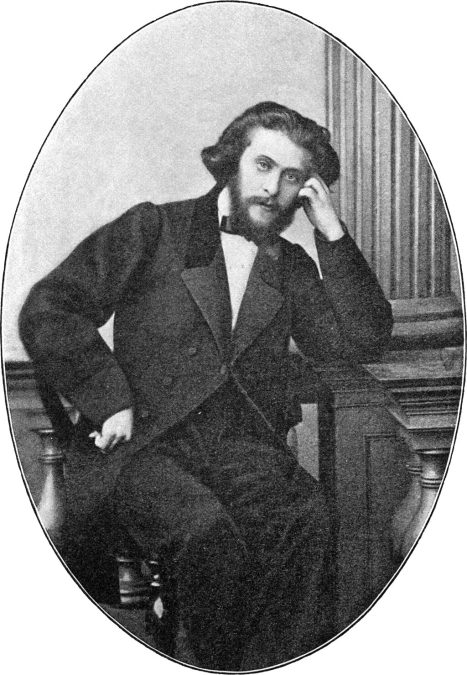

Strange as it may sound, the Russian writer Nikolai Pomialovsky wrote a very similar kind of romantic work in 1861 called Molotov. While it concerned the limitations of class rather than sexual orientation, it was perhaps the Heated Rivalry of his day, offering readers a clean, comprehensible, novel vignette of romantic tension and ultimate triumph at a time of social repression and profound change.

Pomialovsky’s name is probably not familiar if you are not a scholar of nineteenth-century Russian literature, and Molotov has never been translated. If it had, anglophone readers might have a slightly different idea about nineteenth-century Russian fiction. Molotov is a mostly happy, mostly undramatic story. Nothing bad happens. No alienated young man commits murder just to prove to himself he is powerful, as in Crime and Punishment. No married woman commits suicide because she cannot be both mother to her son and public partner to her extramarital lover, as in Anna Karenina. Instead, a young woman and a young man realize that they love each other and, despite initial objections from the young woman’s family, they marry and appear poised to live happily ever after.

This is not the kind of ending that nineteenth-century Russian literature is best known for. But, like the blissful and nearly conflict-free final “cottage episode” of Heated Rivalry, it offers a compensatory fantasy for a society in which basic aspects of a simple, good life are inaccessible for many. A novel can’t give anyone real material access to the good life. But Molotov gave its contemporary non-noble readers a chance to envision themselves living it — something they would never have encountered in literature before.

Molotov was written by the poor son of a clergy family and about lower-class people at a time when both authors and novelistic protagonists from outside the nobility were rare. In 1861, the most celebrated Russian writer was the nobleman Ivan Turgenev. His novels Rudin, A Gentry Nest, and On the Eve established a tradition of melancholy realist prose fiction, in which aristocratic characters love passionately, and — contra the Jane Austen–style marriage plot of the British tradition — never end up happily together. (Turgenev’s most famous novel, Fathers and Sons, was published shortly after Molotov.)

In Pomialovsky’s Molotov, the young protagonist Nadia Dorogova, the daughter of a mid-level civil servant, experiences an emotional awakening by reading Turgenev. She’s convinced, however, that the experiences she has read about are only for aristocrats. She imagines she will only ever experience love mediated by literature in stories about landowners because all of the protagonists in her books, unlike her, live “without worrying about their daily bread.”

The conflict is the same as in Heated Rivalry, where Shane, a romantic at heart but a closeted gay man, is convinced that ordinary romance is beyond his reach. He thus resigns himself to secret sexual trysts with his professional hockey rival, Ilya, struggling to suppress his romantic feelings since coupledom appears out of the question.

Shane’s defeatism is eventually eroded, as Ilya loves him in return. Likewise, Nadia’s relationship with the novel’s other protagonist, Egor Molotov, a mid-level civil servant himself, disproves her cynical theory about romance only being for higher-class people.

Nadia confesses to Egor that she has read Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust, which she found through Turgenev’s novella of the same name. While the novels consume her with romantic emotion, they also feel ridiculously far from her experience. She confesses to Egor, “You must agree it’s funny” that “the daughter of a civil servant” would read Faust.

But Egor mounts a forceful response. The passionate emotional experiences found in Goethe’s and Turgenev’s writings are for everyone because “absolutely everyone” loves. “The poetry of life — love — is not so easy to notice,” he declares. It sometimes “needs to be excavated from the depths of everyday life,” but “it exists for everyone.” Egor wins the argument because Nadia and Egor realize that they are in love.

Molotov’s Modest Radicalism

That Pomialovsky would write a character so convinced that the kind of love one reads about in novels could not be for her gives a sense of how stratified Russian Imperial society was in the 1860s, and how small were the worlds of readers and writers. Pomialovsky expanded both, and Egor and Nadia are themselves representative of the breakdown of the old estate system for organizing and administering Imperial society.

Estate, or “soslovie,” was a heritable administrative category by way of which the state conferred rights, privileges, and obligations. The estates included the nobility, the peasantry, merchants, and the clergy. In 1861, this system was on its way out. Molotov was published the same year Tsar Alexander II signed the abolition of serfdom into law. Although emancipation left peasants without land and thus still dependent on their landlords, it also broke down the most significant distinction between estates. The law no longer separated subjects into those who could own people (nobles) and those who could be owned by other people (peasants).

Neither of Molotov’s two protagonists belong to any recognizable estate category. Egor is orphaned as a child and raised by a professor. He is a “homo novus,” or “new man,” because he has no predesignated place in society. Molotov is the second of two novellas by Pomialovsky featuring Egor Molotov, and in the first, Bourgeois Happiness, we learn how he loses his inborn naivety and is forced to recognize his class status. He is living with a noble family and working as a tutor when he overhears them describing his “plebeian” manners. Humiliated, he leaves and joins the world of St Petersburg bureaucrats.

Nadia’s family story, on the other hand, is one of generational upward mobility. Her great-grandparents “sewed lousy boots” and “baked lousy pies” to get by, but eventually birthed an “entire breed of civil servants.” Nadia’s family has achieved modest comfort, if not wealth or power. By the time Nadia and Egor become engaged, Egor, too, is comfortable. He has been frugal and carefully acquisitive. He has a home full of books and bourgeois objects, decent savings, and free time that he spends at the opera. He no longer has to ask himself “every day, every hour, the unavoidable, torturous questions so draining for the mind: ‘Bread, money, warmth, rest!’” — and neither will his future wife, Nadia.

On first encounter, this narrative of modest upward mobility and heterosexual marriage would appear to be about as radical as a TV show that ends with its gay protagonists planning to found a charity so they can spend more time together. Yet in 1861, characters like Molotov and Nadia from the broad, new, and growing “middle” of society had never been given such a dignified literary existence before.

This was personal for Pomialovsky. His friend Nikolai Blagoveshchensky, writing about Pomialovsky after his death, described how he woke up to the fact that “beyond the confines of the seminary there was another life and other feelings, unknown to the seminarian” after reading Turgenev. Having chosen not to pursue a life in the clergy, Pomialovsky, like Nadia and Molotov, fell outside of estate categories. He chose to make his way by writing, which he thought of as a kind of useful labor akin to teaching or baking bread. He had ambitions (never fulfilled) to form a “society of writer-workers” who would carry out this labor collectively. He wrote essays on education reform and taught workers to read on Sundays.

Molotov was an education project as well, a kind of bridge to Turgenev for other young men and women who might, like Nadia, think such literature isn’t for them. The better world it promises is one in which the “plebeians” partake as enthusiastically in such pleasures as anyone else.

Small Dignities in Dark Times

There were other, perhaps grander approaches to political literature at the time. Pomialovsky wrote for a journal called The Contemporary, which was the primary organ for radical political thought in the Russian Empire in the early 1860s. One of its editors and a champion of Pomialovsky’s work was Nikolai Chernyshevsky, whose revolutionary utopian romance novel What Is to Be Done? was written from prison.

In that novel, the protagonist Vera Pavlovna Rozalskaya also finds happiness, security, and a modicum of freedom through the love of a decent man. But Vera eventually realizes that her love for her husband is platonic, not passionate. He realizes it too and fakes suicide so that she can marry his best friend. As Vera’s desires are allowed to flourish in increasingly mutually satisfying romantic relationships, she eventually realizes that her own happiness is entangled with the happiness of others and that there is no individual freedom without collective freedom. In other words, she achieves class consciousness.

Molotov had the modest aim of making it possible for lower-class readers to imagine a nice life within society as it existed at the time.

Pomialovsky’s novel stops at the first step toward Vera’s revelation, with two decent people in love. It was a comparatively small fantasy — but even so, it was far from the author’s own experience. He was a hopeless alcoholic, and he died in poverty at age twenty-eight from a gangrene infection in his leg.

What Heated Rivalry gives us in this moment, in terms of a useful fantasy, is similarly small. It takes place in a world in which one might reasonably expect more or less progressive parents and friends to be accepting and supportive of the protagonists’ sexuality, and this ends up being the case, despite the characters’ fears. It also takes place within professional male sports, and out gay players are to this day vanishingly rare. Scott Hunter’s spectacular coming out by way of inviting Kip the smoothie guy to come down and make out with him on the ice is hard to imagine unfolding in real life.

But Heated Rivalry has not, primarily, been taken to be a story about gay liberation anyway. As has been much discussed, heterosexual women are its most devoted fans. Its fantasy is less about advancing a vision of a society more accepting of diverse sexualities than it is about offering an array of sensitive and loving men to populate beleaguered women’s imaginaries. Amid the rise of the “manosphere” and the public airing of unapologetic misogyny from the highest echelons of power, it turns out that this is something women are desperate for.

There is only so much that art — literature, film, television — can do, which was part of the point of Molotov. Even Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s revolutionary novel couldn’t chart the path to the better future it called for. What Is to Be Done? ends with a gap in time and a mysterious, brief final chapter that takes place after an undepicted and undepictable revolution. Still, the novel was a sensation for the way it encouraged its readers to imagine a radically remade society.

Molotov had the more modest aim of making it possible for lower-class readers to imagine that a nice life within society as it existed at the time was within reach. Even if that wasn’t true, Pomialovsky seemed to believe that the idea of it would feel good, and that was something in itself. Like Heated Rivalry, it was a kind of emotional medicine for an unbearable time.