Tabitha Arnold: Art Should Not Be an Investment Vehicle for Rich People

Tabitha Arnold is a socialist textile artist whose work focuses on working-class organizing. In an interview, she discusses her work, how art is warped by wealthy patrons’ dictates, and why artists shouldn’t confuse their art with political organizing.

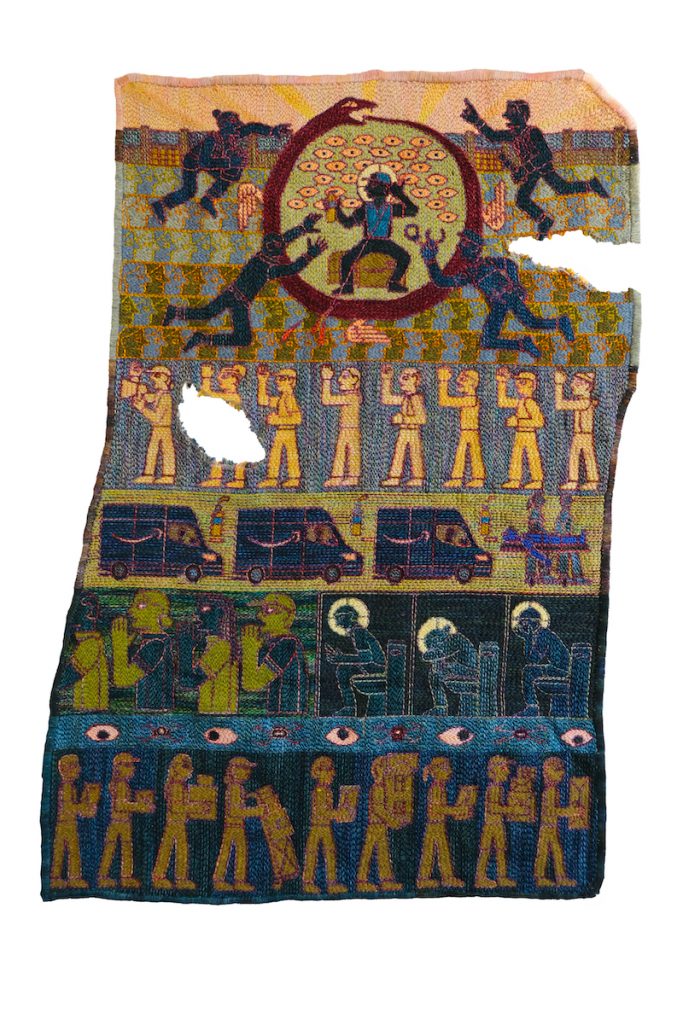

A section of Picket (2021) by Tabitha Arnold. (Courtesy of artist)

- Interview by

- Rachel Himes

Textile artist Tabitha Arnold is crafting an imagery of class struggle for our time. Arnold’s labor-intensive weavings and rugs draw on the aesthetics of propaganda and social realism to present visions of working-class victory and defeat, and show the hard realities of shop-floor organizing, making collective power their primary subject.

In this interview with Rachel Himes, Arnold speaks about her experiences as a working artist and organizer, how she relates to the art world as a socialist, and the roles art and artists can play in the socialist movement.

You’re an artist, an organizer, and, like most of us in the United States today, a worker. Can you speak to how these identities overlap and emerge in your textile and illustration work?

While I feel fortunate to work full-time as an artist right now, in the near future I expect to return to food service or teaching, forms of employment that I have balanced with artmaking in the past. Actually, my time in food service first led me to engage with labor in my art. Making art helped me process and channel the anger and frustration I felt as a café worker in order to achieve the emotional discipline I needed to be an effective workplace organizer. But beyond this personal practice, I came to feel that my work served a practical purpose as propaganda.

Most of your work is produced through, as you name it, the “labor-intensive” process of weaving. For me, resonances emerge between the materiality of your work, the role played by women and immigrant textile workers in labor organizing in the United States and beyond, and, of course, Marx’s twenty yards of linen. What informs your choice of material and process?

I was trained as a painter and hold a BFA in that field, but came to find it extremely siloed and competitive. Maintaining a practice as a painter often depends upon affiliation with elite institutions, but textile work is different.

I first became interested in the medium out of nostalgia for the time I spent watching women in my own family work with textiles. As I became more involved in the community, I came to love how social the craft was. While other art spaces depend on barriers to entry, the fiber artists I encountered wanted to share their knowledge. Technique was passed on rather than hoarded. The practice felt more in line with my own vision for an ideal society in which art is created and circulates through social and collective spaces rather than depending upon individual production and acquisition.

I am also drawn to the role textiles have played in the preservation of the perspectives of working-class and women makers. I’m thinking of the arpilleras created by Chilean women living under Augusto Pinochet. Through these embroidered and quilted textiles, they documented and responded to the regime’s brutality. Textiles are a medium that can convey radical stories without institutional sanction.

There’s something familiar, approachable, and perhaps comforting about textiles. It’s a medium that encourages tactility. How do you want audiences to engage with your work? And in what settings?

People touch my work frequently without invitation, and I had to come to terms with that. I find it productive to compare Western traditions of preservation with Eastern perspectives on craft. A Persian rug can cost more than a house, but it’s still meant to be touched. The art world’s understanding of touch as dangerous and disrespectful also, I think, relates to how art objects function as investments and so need to be preserved to retain their value.

I am trying to give more consideration to how my work can be something that people who are alive now can interact with. I want my art to be for the living, for my immediate community, and not something for a wealthy individual to park money in.

Do you think of your artmaking practice as labor? If so, what does that mean to you?

Yes. In many ways, I think of my art as labor. As a freelancer, I need to exchange my work for money to live. Creating without compensation is not an option for me. And the kind of work that I do requires a lot of time and effort. But it’s also strange for me to think about monetizing my work.

Today, textiles can be considered a form of fine art or artisanal craft, but our ideas about what a rug “should” cost are also shaped by the forces of mass production, which transformed textiles into a devalued and cheap commodity produced through the exploitation of labor. I think a lot about my own position as a producer of textiles in relation to the workers, past and present, who make fabrics and garments in sweatshops and factories.

The theme of repetitive and strenuous labor is strongly evoked in your recent textile Time Off Task. You show rows of workers, some crouched in toilet stalls, others with fists raised in protest. Trucks with the familiar swoop of the Amazon logo appear next to bottles of urine. The rug itself is stretched and warped, with ragged holes. What was on your mind as you worked on this piece? What felt significant to represent about the struggle at Amazon?

When I think of Amazon, visceral images come to mind. I remember reading a whistleblowing article in Philadelphia’s Morning Call which described workers passing out in warehouses without air-conditioning and being wheeled out on stretchers as work continued around them. My younger sibling, who worked in a warehouse for a couple of years, shared similar stories with me.

But I didn’t want to only show the violence of these conditions. I wanted to document the struggle of the Amazon Labor Union from a workers’ perspective. I think this desire arises from my own time as a café worker and organizer. My bosses would try to tell me about my own experiences in the workplace and it made me feel crazy. I kept that feeling in mind as I made this piece. And to me it recalls the power of the one-on-one organizing conversation. When workers connect over their shared experience, the result is transformative.

A few of your woven rugs are populated with angelic figures. For Marxist viewers, these might bring to mind Walter Benjamin’s angel of history, which he saw visualized in Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus, who perceives with wide eyes the catastrophic wreckage of history piled before him. Who are these angels, and what do they herald?

Growing up in the Bible Belt, I became very familiar with Christian ideas about angels. The most well-known story is probably the Annunciation, when Gabriel appears to the Virgin Mary, but that’s not how angels function in my work. Instead of announcing the arrival of a savior, they refer to the Book of Revelation and its fantasy of justice, of revenge, and the final unleashing of God’s wrath upon the world.

For me, angels represent the righteous power of workers, suggesting a force that will meet and destroy the capitalist ruling class and put an end to the wrongs they inflict upon us. Those who have suffered won’t go unremembered. The wrongs they have experienced will be met with justice. Angels are symbols of power, of this unstoppable force. To me, that’s the Revelation idea. If there’s a hell, then it is for billionaires.

Your textiles marry the imagery of social realism with the visual language of religious art. It seems that both traditions place great emphasis on the communication of certain values and principles to broad audiences. How do these traditions interface in your work?

I am drawn to the communicative power of both social realist and religious art to visualize a fantasy or an ideal. I think I also use religious symbols to reflect on my own upbringing. I grew up in a fundamentalist Christian community that promoted a denial of the self that I came to realize I was still carrying as a nonreligious adult. I had learned to deny my own feelings and my own physical being in order to submit to authority, and this came up for me as a worker and an organizer.

American Christianity and capitalism collude to produce a hierarchical structure in which the boss becomes someone who has moral authority over you. It’s so important to realize, as workers, that the conditions we are required to submit to are actually not okay, and that we can do something about it. I want to reclaim some of those Christian images and symbols on behalf of the working class, so the Christian right doesn’t hold the patent on those teachings.

I also feel my work makes a case for a recognition of spirituality and religion on the part of the socialist movement. Spirituality — and in America, especially Christianity — is important to so many working people. It’s something to engage with, especially the role it has played in the lives of people who are struggling.

While I believe that art is deeply valuable for both the socialist movement and in our own lives, it’s not always easy to make strong arguments for that value. How can we on the Left better articulate the significance of art and artmaking, both in the world we are trying to win and in the fight for that better world? What role can artists play in the movement, as artists? What other roles can they play?

We’re fighting for a future in which people are liberated to create if they feel creative and in which we all are able to receive that work in a social way, and in a way which is not shaped by the monetary value of art. Making and experiencing art is a joyful work of our lives. We all deserve it. Art is also useful as a tool in the struggle for that world.

But while there is certainly a practical application for art in organizing, as propaganda, I don’t see artmaking on its own as a form of organizing, and I think there is a danger in considering it as such. That’s something that elites and institutions would like to represent as the truth, since it redirects or subverts challenges to their authority.

As artists, we can’t fall prey to the myth that just because we are making political work, we don’t therefore need to participate in collective forms of struggle with workers, tenants, or other communities.

I’m saying this as someone who spends a lot of my time just making art. I’m trying to challenge myself to stay involved with organizing with Philly Socialists and with the Democratic Socialists of America. I guess I have some paradoxical opinions: I think it’s important to challenge the idea that art is organizing on its own, but still think it’s critical to use art as a tool to imagine a socialist future. It can be really helpful and meaningful to present an image of how things can be different.

A struggle for me, as a labor organizer, was being confronted with my coworkers’ seeming inability to imagine that different future. It’s hard to even conceive of a world where a service-industry worker makes a living from their job. That’s part of my attraction to the Mexican muralists like Diego Rivera and to social realism. I think they were onto something in terms of presenting that future to the public as a way of affirming, This is what we want and we can have it. This is possible.