Resurrecting Thomas Sankara

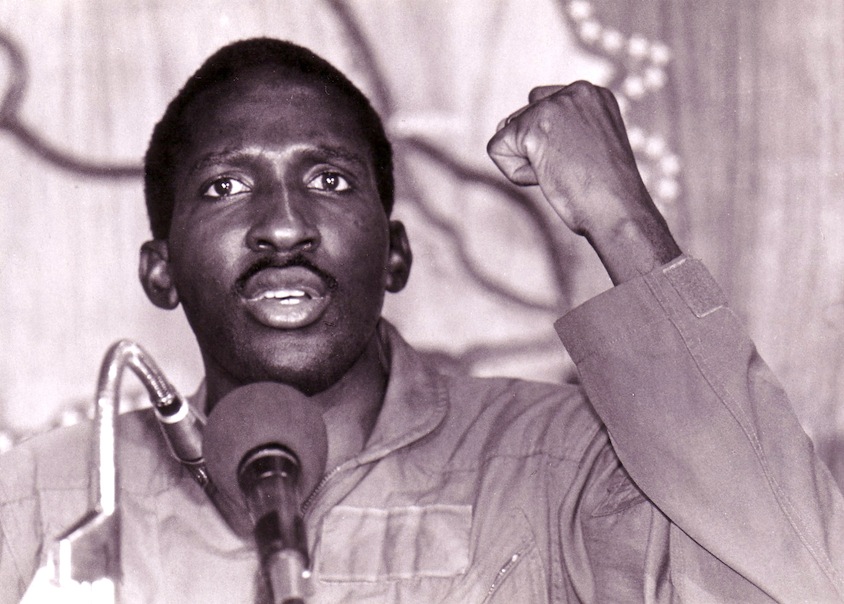

Nearly thirty years after his assassination, African revolutionary Thomas Sankara is still inspiring the struggle for self-determination.

Fadel Barro, a central leader in the Senegal youth movement Y’en a Marre (Enough), is gaining a reputation among activists across Africa. In 2011 Barro and Y’en Marre initiated a mass attempt to block then-President Abdoulaye Wade from amending the constitution to favor his reelection. More recently, Barro and several dozen other activists were detained for several days in the Democratic Republic of the Congo for criticizing that president’s unconstitutional efforts to hang onto power.

In his public appearances, Barro often wears a favorite T-shirt: on the front is a picture of Thomas Sankara, the late revolutionary leader of Burkina Faso, with the words, “I’m still here.”

Barro isn’t alone in his veneration. While Sankara has been popular among youths across Africa for some time, in recent years interest in Sankara’s example and ideas has seen a resurgence, particularly in Burkina Faso itself.

Sankara was assassinated in a 1987 military coup that halted a nascent movement for progressive change and justice in Burkina Faso. His growing popularity is connected with deep discontent among Burkinabè, who ousted President Blaise Compaoré — the captain responsible for Sankara’s death — during a popular insurrection in October 2014.

Africa’s Che Guevara

In the months of demonstrations leading up to Compaoré’s ouster, symbols of Sankara were virtually everywhere. Protesters carried his portrait, and his recorded voice rang out over sound systems. Quotations from his speeches were featured in popular chants. Even politically moderate opposition leaders often concluded with the emblematic slogan of Sankara’s revolutionary government: La patrie ou la mort, nous vaincrons! (“Homeland or death, we will win!”)

The leaders of the main opposition parties — a few of them “Sankarist” but most with other perspectives — played important roles in initially calling the demonstrations. However, it was activist circles and youth networks that rose up and confronted the regime’s security forces, with several dozen protesters sacrificing their lives in the process.

Many of these groups, such as Balaï Citoyen (Citizens’ Broom), openly count Sankara among their heroes. As demonstrators marched on the National Assembly building on October 30 (before burning it down), they chanted well-known Sankara slogans like “When the people stand up, imperialism trembles.” Al Jazeera reported that many young protesters were inspired by the spirit of “Africa’s Che Guevara,” while the Paris daily Le Monde declared Compaoré’s overthrow “the revenge of Thomas Sankara’s children.”

Two weeks after Compaoré fled the country, a transitional government was formed to organize new elections by October 2015. The cabinet is diverse — technocrats, intellectuals, army officers, civil society figures, a few radical activists — and includes a number of pro-Sankarists.

Michel Kafando, the retired diplomat who serves as transitional president, praised the revolution’s “egalitarian development model.” His prime minister, Lt. Col. Yacouba Isaac Zida, extolled the “identity of integrity that we have carried proudly since the August 1983 revolution.” A new transitional parliament has also been established, headed by Chériff Sy, an independent newspaper editor known for his admiration of Sankara.

As longtime opponents of Compaoré, those who openly identify with Sankara’s legacy now wield considerable moral authority, bolstered by the living memory of Sankara among many Burkinabè. They and other activists are pushing for fundamental reforms in the political and social system and for justice in the most serious cases of human rights abuses and corruption under Compaoré.

Investigations have been reopened into investigative journalist Norbert Zongo’s 1998 murder (presumably by members of Compaoré’s presidential guard), and for the first time ever, a judicial inquiry has been launched into the assassination of Sankara himself.

Regardless of the circumstances of Sankara’s death, it is the actions and ideas of his lifetime that attract the greatest interest today. The durability of his legacy is all the more notable considering the very short time his revolutionary government was in power — from August 1983 to October 1987.

In retrospect, many Burkinabè — whether they liked that government or not — agree that it brought more positive changes to the country than had occurred in the previous twenty-five years of national independence.

“Land of the Upright”

When Sankara’s National Council of the Revolution (CNR) seized power in August 1983, the foreign media generally described the takeover as a military coup — just another among many across Africa.

Sankara was an army captain, and a number of key colleagues (including Compaoré at the time) were officers. But they overthrew the previous military junta as part of a broad political coalition that included several leftist political groups, some trade unions, the student movement, and other civilian activists. The CNR and its cabinet were hybrid institutions that drew participants from various sectors of society and attracted strong and active support from the young, the poor, and others marginalized by the old order.

The young leaders of the CNR (Sankara was just thirty-three at the time) made it clear from the outset that they were not interested in making a few modifications at the top. They wanted to fundamentally transform the country — one of the poorest and most underdeveloped in the world. To underscore that rupture, they changed the nation’s name from Upper Volta, the old French colonial designation, to one that asserted African identity: Burkina Faso, or “Land of the Upright People.”

The country’s foreign policy also took a sharp turn: away from alignment with France and other Western powers, towards anti-imperialist, revolutionary, and radical nationalist movements and governments across the “Third World.” Sankara’s CNR openly and actively supported Southern African freedom fighters — the first new Burkina Faso passport was symbolically issued to Nelson Mandela, then still imprisoned in apartheid South Africa.

The Sankara government also backed various movements that directly opposed French domination. During trips to Latin America, Sankara embraced Fidel Castro, as well as Nicaraguan revolutionaries resisting US intervention. Within Africa, Sankara and his comrades championed a model of pan-African unity based on mobilized populations — not just verbiage, as was the case with most of the continent’s rulers, who generally retained strong links to their Western allies.

Unsurprisingly, the CNR aroused the enmity of France, the US, and other powerful nations. Their African client states, especially in neighboring Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, and Togo, attempted to destabilize the Sankara government. They helped dissident military officers carry out bombings, and in 1986 Mali even waged a brief war against Burkina Faso.

Overhauled State, Mobilized People

Burkina Faso’s radicalism was not just for external consumption. Sankara’s governing council made it clear that while some changes would necessarily take years, it would not limit itself to incremental reforms. The “supreme task” of the revolution, Sankara pledged, “will be the total reconversion of the entire state machinery, with its laws, administration, courts, police, and army.”

In addition to restructuring the judiciary, the military, and other state institutions, Sankara’s governing council attacked corruption and conspicuous consumption by the nation’s elite. Frugality and integrity became the new watchwords, and public trials sent scores of dignitaries to jail for embezzlement and fraud. Government ministers had their salaries and bonuses cut and their limousines taken away. Sankara publicly declared all his assets, kept his own children in public school, and rebuffed relatives who came seeking state jobs.

More fundamentally, the CNR aimed to develop a new politics by promoting robust ties between the reformed state and a newly mobilized citizenry. In his first radio broadcast as president, Sankara appealed to everyone, “man or woman, young or old,” to form popular organizations known as Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs). Directly elected by general assemblies open to all residents of a particular neighborhood or village, CDRs soon spread throughout Burkina Faso. The local committees were genuinely popular, filled with people from humble social origins, not just the educated few.

Widespread collective labor mobilizations began within a few weeks of Sankara’s takeover. The initial calls came from the central authorities, but at the local level they were usually initiated and organized by the CDRs.

During the first few years, mobilized communities undertook an array of projects: cleaning school and hospital courtyards, graveling roads, building mini-dams to capture or channel scarce water for farm irrigation, and, when building materials could be secured, building schools, community centers, theaters, and other facilities. Resident efforts sometimes exceeded the government’s capacity to carry them through — for example, building more schools than the authorities could staff or supply.

The mobilizations, moreover, were not a CDR monopoly. Although relations with most of the established trade unions were complicated and sometimes turned tense, scores of new self-help organizations emerged across the country, many without any direct connection to the central government.

Sankara was open about his ideological beliefs: Marxist, non-dogmatic. Since Burkina Faso was extremely poor, with little industry and a tiny wage-earning class, he took care not to tag the labels of “socialism” or “communism” onto the revolutionary process. Instead, he framed it as “an anti-imperialist revolution” focused on fighting external domination, constructing a unified nation, building up the economy’s productive capacities, and addressing the population’s most pressing social problems, such as widespread hunger, disease, and illiteracy.

Although poverty remained a painful reality for most people, the four short years of Sankara’s CNR started to bring slight improvements in living conditions: new health clinics across the country, hundreds of new schools, an adult literacy campaign, and greater support for poor farmers. Alongside rigorous austerity for state officials (especially high-level bureaucrats), public spending on education increased by 26.5% per person between 1983 and 1987, and on health by 42.3%.

Some Western countries continued to aid Burkina Faso’s development efforts, but many — leery of the government’s politics — reduced funding. In this climate, Sankara and his colleagues emphasized the need to be as economically self-sufficient as possible. They avoided accepting development aid thatcame with political strings attached. “We know we have to depend on ourselves,” Sankara said.

Especially in such an arid country, that also meant being environmentally sustainable. Hundreds of new wells were dug and reservoirs built to better conserve the little water the country had. Farmers were taught how to combat soil erosion and produce organic fertilizer. Millions of trees were planted across the countryside. In this concern for the environment, Sankara was notably in advance of most other African leaders.

Sankara was also ahead of his time in stressing women’s rights. Many social and economic programs included specific measures such as women’s literacy classes, maternity training in rural villages, and support for women’s cooperatives and market associations. A new family code set a minimum age for marriage, established divorce by mutual consent, recognized a widow’s right to inherit, and suppressed the bride price. Public campaigns sought to combat female genital mutilation, forced marriage, and polygamy.

At a time when few women reached high political or administrative positions in Africa, the Sankara government appointed women as judges, provincial high commissioners, and directors of state enterprises. In each of Sankara’s last two cabinets in 1986 and 1987, there were five women ministers, about a fifth of the total. (One of them was Joséphine Ouédraogo — now minister of justice in President Kafando’s transitional government.)

As in other revolutionary experiences in Africa and elsewhere, differences emerged within the central leadership. Some of Sankara’s comrades were ideological followers of Stalin, Mao, and Albania’s Enver Hoxha. They were less concerned than Sankara about the abuses of some CDRs, were intolerant of dissent, and tended to favor coercion, including arresting outspoken trade unionists.

Gradually, these hardliners gravitated towards Compaoré — the minister of defense, who was tied to the politically conservative and pro-French president of neighboring Côte d’Ivoire.

Sankara’s Enduring Relevance

On October 15, 1987, Compaoré’s followers carried out a coup, assassinating Sankara and a dozen of his aides. Burkinabè were shocked and terrified, and popular mobilizations collapsed overnight. The Compaoré regime eventually scuttled most of the progressive policies and programs of the Sankara era.

Some Sankara opponents try to minimize his legacy, arguing that during his time in office abuse and repression occurred. They accuse his followers of perpetuating a stylized “myth.” Sankara’s revolutionary project was not perfect and should not be idolized. The military continued to play an inordinate role, the CDRs are remembered more for their abuses than their positive role in mobilizing communities, and the authorities had little tolerance for political dissent.

But many Burkinabè still recall the Sankara era’s great strides in promoting people’s health and education, its innovative development initiatives, its vigorous anti-corruption measures, its progressive foreign policy, and its emphasis on social justice, women’s rights, and youth empowerment. As a result, Sankara’s ideas are gaining widespread reconsideration, and deservedly so.

Sankara is not just a colorful figure from the past or a freedom fighter for the history books. He is a “living myth,” as one of Burkina Faso’s leading daily newspapers recently put it. “His ideas continue to mobilize unimaginable crowds.”