Is Cormac McCarthy “Based”?

Legendary novelist Cormac McCarthy is often hailed by the Right as one of its own. The truth is more complicated.

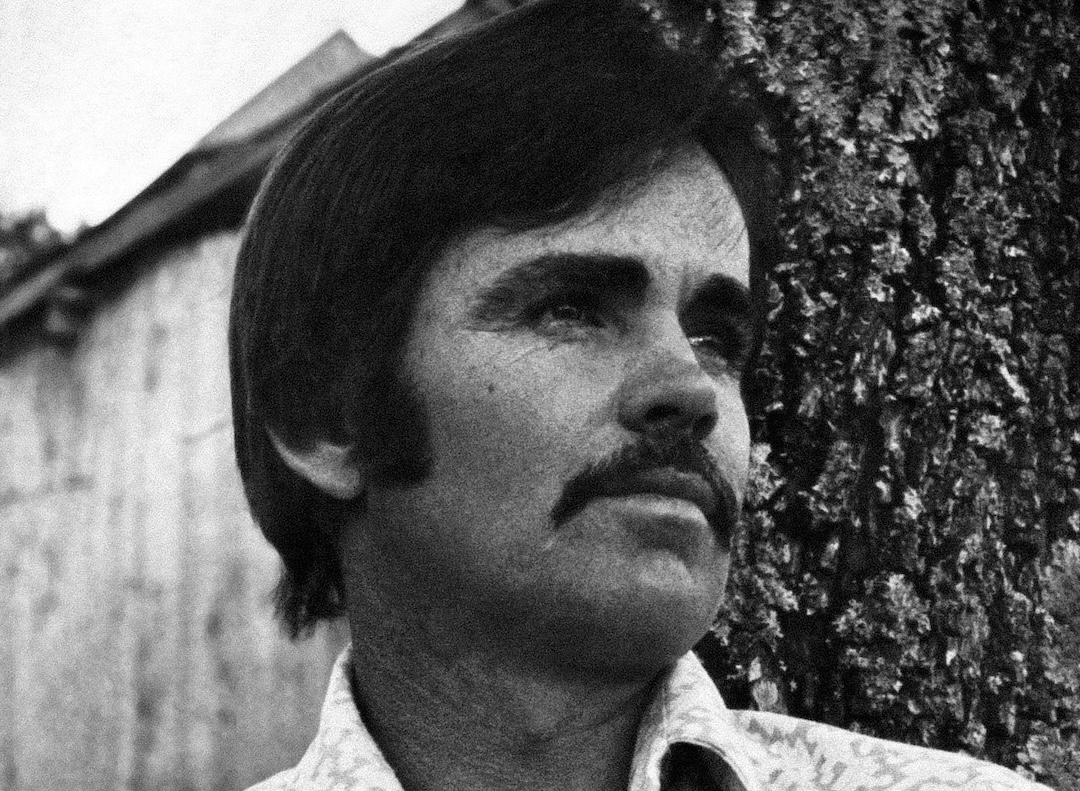

Incest, cannibalism, necrophilia, murder, and war on a metaphysical level are often-favored Cormac McCarthy topics. (David Styles / Wikimedia Commons)

If there was ever an author who screamed “the great American novelist,” it’s Cormac McCarthy. From 1965’s The Orchard Keeper to the twinned publication of The Passenger with its companion novel, Stella Maris, shortly before his death in 2023, McCarthy produced a body of work which has been seriously (and reasonably) compared with not only that of Herman Melville and William Faulkner but even biblical scripture in the depth of its spiritual aesthetics.

This is in spite of the intense demands his fiction makes on readers. These aren’t so much formal; some of McCarthy’s fiction is experimental and odd, but little that rises to the opacity of literary icons like Thomas Pynchon, William Burroughs, or even Faulkner. Rather it is the extreme, albeit highly stylized violence and darkness of books like Blood Meridian that led even seasoned ultra-readers like Harold Bloom to initially recoil. Incest, cannibalism, necrophilia, murder, and war on a metaphysical level are often-favored McCarthy topics. Even gentler novels like the aforementioned duology The Passenger/Stella Maris focus on the unconsummated romantic and sexual desire of a brother and sister for each other.

This savagery and its attendant pessimism have contributed to many reading McCarthy as fundamentally a conservative author. Simplistic readers admit to being attracted to his allegedly “tough masculinity,” centered around cowboy protagonists having to survive in the deep country. More thoughtful right-wing critics stress McCarthy’s deep (if ambiguous) religiosity and critical account of human nature as evidence for his conservatism. Readers like Alexander Riley see McCarthy as defending the traditional wisdom of rootedness. For Riley, McCarthy rejects the destructive, Faustian metaphysics of liberal and socialist modernity, with its utopian application of ever-more-refined science to dominate nature and man in the name of libertine gratification, for a more modest appreciation of limits.

Of course, there’s no doubt textual evidence for a more straightforwardly reactionary interpretation. In No Country for Old Men, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell — memorably played by Tommy Lee Jones in the film adaptation — echoes conservative ruminations on decline when he predicts that, the way the country is going, not only will abortions be plentiful and unrestricted but the children allowed to live will in turn one day have the right to euthanize their parents.

McCarthy himself seemed to add credence to a conservative reading of his work. In one of the few directly political statements he’s ever made, McCarthy warned that the

notion that the species can be improved in some way, that everyone could live in harmony, is a really dangerous idea. Those who are afflicted with this notion are the first ones to give up their souls, their freedom. Your desire that it be that way will enslave you and make your life vacuous.

This dark warning came in 1992, when many intelligent liberal commentators thought the “end of history” heralded a new age of peace and humanity. McCarthy could only offer a smile that grew more joyless as the new century dawned.

McCarthy’s Politics

Conservative readers of McCarthy are correct to highlight his anti-utopianism and deep conviction that the moral improvement of the species as a whole was impossible. In McCarthy’s fiction, limits are to be embraced. But that’s not necessarily a conservative stance: that wealth and power corrupts is a great argument for why we shouldn’t have a capitalist system where so much is allowed to be concentrated in a few hands. And a recognition of shared human finitude and fragility certainly has been the basis of leftist arguments for cooperation and equality since the earliest Christians.

As we’ll see, this was a view McCarthy shared. While nominally agnostic, McCarthy was raised Roman Catholic. They say the hand that rocks the cradle makes the man — and the communitarian themes of a humane Catholicism are all over his work. Conservatives elide the extent to which McCarthy characterized their own sacred idols as exemplars of the Faustian and even darkly utopian aspirations he stood firmly against.

Blood Meridian is undoubtedly McCarthy’s masterpiece, even if it is probably the most disturbing — though Child of God, which follows the life of a serial killer and backwoods necrophiliac, might give it a run for its money. Blood Meridian’s central protagonist is “the Kid,” who lives on the American frontier in both a physical and liminal sense. In McCarthy’s hands, the history of American expansionism, nationalist exceptionalism, and racism becomes a microcosm of human folly leading to moral disaster. In the opening sections of the book, the Kid joins the party of Captain White (McCarthy is not always prone to subtlety) who is leading a band of mercenaries deep into Mexico, even though the Mexican-American War is now over. White sneers that they are dealing with

a race of degenerates. . . . There is no government in Mexico. Hell, there’s no God in Mexico. Never will be. We are dealing with people manifestly incapable of governing themselves. And do you know what happens with people who cannot govern themselves? That’s right. Others come in to govern for them.

White insists that if Americans don’t “take their country seriously,” soon enough they will fly a European flag. Captain White is tragicomic in his less-rare-than-one-would-wish combination of rank stupidity and unearned arrogance, White leads his merry band of patriots to their deaths, and his head later ends up pickled in a jar of mezcal. One suspects McCarthy grimly mused that not a lot of moral seriousness and deep thinking was being lost by this transplant.

Later in the book, things get darker still as the Kid joins the Glanton Gang, led by the archetypal Judge Holden. There are many literary precedents to Holden, ranging from John Milton’s charismatic Satan to Melville’s Ahab and Friedrich Nietzsche’s Overman. But the singularity of the Judge’s existence is such that he defies easy reduction into any political or philosophical outlook. As McCarthy notes late in Blood Meridian, there is no “system by which to divide him back to his origins for he would not go.” Holden’s own philosophy can be summarized by the dictum “war is God.”

Echoing the darkest Adornean underbelly of the Enlightenment, the Judge collects samples of every creature and plant he encounters to study them in order to better achieve control. As Holden once put it: “Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent,” embodying the ultimate reductio of Francis Bacon’s scientific mantra that knowledge is power and must always be. Scientific knowledge, in Holden’s case, is utterly divorced from moral improvement. Not only improved means to unimproved ends, but improved means to war. All other human activities are either inferior approximations of war or contribute to it. Holden admires war as a “forcing of the unity of existence” by elevating the spiritual intensity of life to its apex, subordinating all other values to the struggle for survival and control. For the winner, the prize is not just to continue existing but to subordinate the existence of others to one’s will. War is the most divine enterprise, seizing the power to choose what exists and what can be refused existence for one’s self and denying it to everything and everyone else.

It’s rewarding to read this at a metaphysical level while ignoring the concrete backdrop of McCarthy’s tale. The Glanton Gang enthusiastically wipes out the indigenous tribes of the West to make money off their scalps, and McCarthy foregrounds their participation in the savage genocide in methodical detail. While nominally doing it for money, in a deeper sense the Glanton Gang is following Holden’s philosophy. The historical specificity of McCarthy’s account makes clear the extent to which American exceptionalism and imperialism don’t emerge out of some superior national virtue. Rather it is the very ordinary human capacity to hypocritically rationalize giving into the temptations of chasing power after power. After all, every empire has acclaimed itself the avatar of destiny and wound up falling into the abyss. Holden and the Glanton Gang are acting as agents of America, acting on the Satanic drive for power after power that expresses itself in the mass extermination of the indigenous peoples. One can’t help but think of Karl Rove’s injunction that America is “an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.” Or more contemporarily, Donald Trump’s banal celebration of military might and flirtations with starting yet another Middle Eastern war.

One of the great evils committed by Holden as well as McCarthy’s other villains is a rejection of community. This theme reaches its apex in his early twenty-first century works like his play The Sunset Limited and novel The Road. In The Sunset Limited, the arch-academic “White” has used his enormous intellect and learning to convince himself into nihilism and abject misanthropy. When the play starts, he’s just been rescued from a suicide attempt by “Black,” a working-class felon-turned-preacher and the only other character in the play.

With White, one is reminded of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Ivan Karamazov, whose overpowering intelligence led him to a horrible dialectic where each conviction and belief twisted into its opposite and everything became permitted because nothing mattered. White insists that the things he believed in don’t exist anymore because “Western civilization finally went up in smoke in the chimneys in Dachau.” Notably in both The Road and The Sunset Limited, McCarthy posits communion as the only spiritually correct response to material and intellectual negation. But White refuses even the community of the dead, insisting he wants to be “dead” because “that which has no existence can have no community. No community! My heart warms just thinking about it. . . .” Whereas in The Road, humanity has so degenerated into crude individualism and tribalism in the face of apocalyptic decline that there is nothing left to do but eat each other. But even in the bleakness of that novel, we have glimmers of hope emerging from the powerful bond between father and son. As he dies from his wounds, the father makes his son promise to “carry the fire” of hope forward, which eventually leads him to the very near-literal deus ex machina of finding a new family. The blood that was unchosen becomes, instead, blood chosen.

But with McCarthy, it is not simply an abstract, cultural community, let alone one based on the banal racial nationalism increasingly popular on today’s right. In The Road, scarce moments of humanity are achieved by sharing what little one has with others. In The Sunset Limited, the black felon-turned-preacher tries to be a true brother to the academic, though the play’s bleak ending suggests that when one falls so low sometimes even that isn’t enough.

McCarthy’s Celebration of Difference

McCarthy ruminates about how true evil is characterized by a tendency to think in absolutes. Absolute good and bad, natural and unnatural, them vs. us are the simplifying bifurcations that provide a certainty that occludes the truth. Absolutism offers the clarity needed to make it easier to do whatever we think we must in order to obtain our ends. At its worst, this yearning for certainty completely swallows the substance. McCarthy’s two archetypal villains, Judge Holden from Blood Meridian and Anton Chigurh from No Country for Old Men, represent different aspects of this tendency to subordinate all the world to a singular purpose.

Holden is incapable of allowing anything to exist without his consent, whereas Chigurh totally abnegates any moral responsibility for his actions. Instead, Chigurh prefers to identify himself as a necessary deterministic force of nature, softened only by the occasional mercy he might show depending on the literal flip of a coin. In both cases, their subjective worldviews consume the rest of the objective, material world. As McCarthy put it in The Passenger, “Evil has no alternate plan. It is simply incapable of assuming failure.”

By contrast, McCarthy’s most sympathetic protagonists are always far from perfect, and never monomaniacal. Instead, they humbly accept the finitude of their existence and seek community in the world abroad. This usually takes the form of becoming a wanderer and traveler of some kind. Far from being embodiments of “traditional” — let alone “American” — wisdom, All the Pretty Horses’s Grady Cole and The Passenger’s Bobby Western leave the dissatisfactions of home in search of experience with others. They are fundamentally individuals who live on the symbolic “border” and embrace others willing to do the same. It’s very hard not to read this as an affirmation of otherness (dare I say “diversity”?), grounded in an appreciation of others not required to be perfect but only to share themselves.

If this offends the conservative McCarthy aficionado, they only need to think back to his autobiographical novel Suttree. Suttree sympathetically chronicles the lives of ne’er-do-wells, petty criminals, drunks, and weirdos living in Knoxville, Tennessee. The novel’s autobiographical connections are sometimes very on the nose. In The Cambridge Companion to Cormac McCarthy, Lydia Cooper writes about how Cornelius Suttree’s conservative and conventionally successful father writes him a letter expressing disappointment that his son hasn’t gone into a more typical career. He criticizes Suttree hanging out with a bunch of lowlifes and working-class stiffs he considers beneath the family. In real life, McCarthy had abandoned the dull life of middle-to-upper-middle class conformity for the bohemian career of a writer. For the majority of his writing life, he was exceptionally poor; so poor the family couldn’t afford toothpaste. This often took him to some very dark places, but McCarthy was capable of enormous empathy as well.

In Suttree, Cooper notes, “The symbolic cataracts that transform the streets of Knoxville into a freak show simultaneously reveal an essential truth about the human condition, a truth to which Suttree’s father, with his ability to distinguish between power and failure, is blind.” She stresses that, for McCarthy, it is only when we commune with others who share our helplessness and impotence that genuine companionship is possible. The emphasis on superiority and hierarchy so central to the Right precludes the formation of such community.

The Passenger’s protagonist is Bobby Western — a genius physicist long in love with his equally brilliant mathematician sister, who commits suicide when the novel begins. Tormented by guilt and uncertainty, the novel chronicles Western’s travels around the United States and beyond. Haunted by his sister’s memory, he becomes increasingly aware that all the tools of reason will never give a firm answer as to theists’ best rejoinder to atheists: Why there is something instead of nothing and thus a way of explaining the necessity of human suffering and folly. As emphasized in both The Passenger and Stella Maris, one of the great horrors of human life is coming to awareness that the universe is, seemingly, utterly unaware of us. Western searches for the community and meaning that can replace the sense of loss over the most forbidden of loves and recognition of the limits of intellect. He befriends Debussy Fields, a trans woman with a complicated history. Always referred to as “she,” Debussy is no saint. Her frantic style and tendency to overshare contrasts with the often-reserved Western, and their friendship is somewhat surprising for reasons of personality. But it’s very clear that Western cherishes Debussy closely, and McCarthy offers a warning to those who’d fail to see why:

“He watched her until she was lost among the tourists. Men and women alike turning to look after her. He thought that God’s goodness appeared in strange places. Don’t close your eyes.”

Cormac the Catholic

I think the closest analog to McCarthy’s political philosophy is nothing so crude as contemporary conservatism or that of the twenty-first-century Right. Instead, his writings remind one of no less than Alasdair MacIntyre, the great Catholic Marxist critic of modernity who recently passed. MacIntyre shared McCarthy’s wariness of the Faustian proclivities of the modern world, in both their left and right guises. He was deeply critical of how libertine permissiveness could lead to passively nihilistic hedonism at best and active assertions of the will to power at worst.

Like McCarthy, who relentlessly lampooned the striving after wealth and power, MacIntyre was also aware of the extent to which capitalism both reflected and abetted these most corrosive of human tendencies while having few illusions it could be replaced at a word. And both writers despised hoary nationalism. McCarthy never missed an opportunity to lampoon it, whether with Blood Meridian’s flag-waving blowhard Captain White or The Passenger’s sneering at Cold War paranoia and Red Scare irrationalism. MacIntyre thought the idea of the superior “nation” was one projected by the powerful to manipulate the masses and mused that being asked to die for the nation was the moral equivalent of giving up one’s life for the telephone company. For both McCarthy and MacIntyre, nationalism was a golden idol, and the intensity of worship directed to the nation was directly inverse to its moral smallness.

But in a more positive sense, there is a yearning in both writers for an egalitarian community that imposes moral obligations while enabling the free and full expression of individuality on the part of its members. Human beings cannot be ethically perfected as a species. Yet a community that appreciated the variety of its members and saw the value their unique identities and approaches to life brought others merely through being would be one where it was easier to cultivate virtues and resist the temptations of domination.

Ethical universalism imposes enormous demands on us to treat everyone we can as brother and sister; so great, in fact, that we’ve yet to truly figure out how to live humanely with one another. What McCarthy teaches the Left is the necessary importance of the human soul for this project, which is easy to dismiss with vulgar materialism. Reactionary thinking goes too far in the other direction — by marginalizing the materiality of the other and his or her suffering, it mutilates the soul by hardening it and turning it inward in the name of egoism and nationalist chauvinism.

The Right’s latest banal rants about “suicidal empathy” are testament to the one-dimensionality that comes from embracing the reactionary worldview. But the Left is by no means perfect — instead of scoffing at the idea of “virtue,” they should learn, from both McCarthy and MacIntyre, virtue’s incredible necessity. Not only for promoting the everyday goodness so essential to forming real communities, but so that those communities — and that virtue — can expand ever further. It is simply not enough to love humankind in the abstract if we love actual human beings far too little. Being good to others everyday is what is needed to prevent the ethically correct, concrete universalism of the Left from becoming a mere abstract universalism devoid of real commitment.

At the end of The Passenger, Western has decided to live on a small island that reads like an upscale version of Suttree’s bohemian Knoxville. It’s filled with eccentrics and world travelers, who enjoy each other’s company and support one another but who refrain from imposing a rigid moralism on the society’s members. Western ends the novel as content as any of McCarthy’s usually tragic protagonists can be in an imperfect world. This includes Western’s sister Alicia, who in Stella Maris succumbs to her demons while self-isolating in an asylum conversing with a therapist.

The implication is that the answers to the riddles of existence aren’t to be found in the starry heavens above or some abstraction within. It’s through the recognition of others that we find our place. At the close of The Passenger, Western hasn’t found utopia, because that is no place that ever can be found. But he found others who helped Western find himself. One might imagine him happy.