On Anger and “Meaning It”

There's no need for excessive complexity — some people are worth hating.

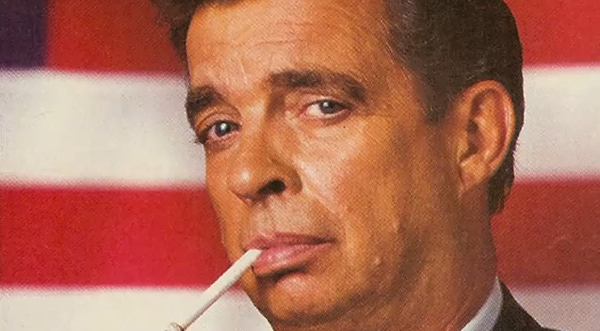

So apparently there’s a new documentary about Morton Downey Junior out. People like to talk about how the great things they read when they were young stuck with them like nothing else but of course it’s also the crap that sticks to us. I don’t think I actually watched his show, though I certainly watched a lot of crap when I was in junior high and high school. But I have a clear image of him, in super close up, smoking, holding a noose, saying some one or other should be strung up by his testicles in it. I think maybe it was flag burners. Remember the flag burners?

Now if someone described someone with a noose on TV screaming about who should be killed in what manner for having the wrong beliefs or whatever, and you didn’t know the time or place, probably you might say this is a dangerous person. We might say “fascist” without being accused of hyperbole. But from the description, it sounds like the documentary makers are more interested in him as a kind of media pioneer, paving the way for the Glen Becks who walk among us, “important” in some way, worthy of more than the expected liberal handwringing. And while I’m all for avoiding the predictable liberal hand-wringing, there’s something equally tiresome about liberals bending over backwards to lend “complexity” to their discussions about the people who just plain hate them. I’ve been trying for a while to write something about how David Foster Wallace (not exactly a liberal but close enough) falls into this — how he was so much less smart about politics than he was about everything else. His profile of a B-list shock jock is typically brilliant in dissecting all the rhetorical and psychological tics of its subject, but in the end, you don’t really end up with something that different from: white dude pissed off that people are daring to speak back to white dudes.

Presumably the filmmakers, like Wallace, would find the position of righteous indignation towards Downey tiresome and predictable. He’s a buffoon, an entertainer, representative of something or other about relentless American self-invention and so forth. He’s an entertainer, and presumably “he didn’t really mean it.” But of course we’re quick when it’s other places and times to say those who seem like buffoons can be the most dangerous. In any case, at fourteen, I didn’t know I was supposed to make those distinctions. I thought he was completely terrifying.

As a kid in the eighties and a teenager in the late eighties and early nineties, AIDS had far more of a impact on me than anything else that was roughly construed as a “political issue.” I remember watching The Day After — or maybe I just remember people talking about it — and I remember asking my mother why there was this strange commercial on TV about a bear. But this fear was abstract, philosophical. AIDS was visceral. I remember my parents recording the 5:30 NBC news every night on the VCR and the sound of Robert Bazell’s voice signing off his dispatches from the NIH, the graphics of the cells that would come and invade your body and turn it against itself. I remember my parents watching the McLaughlin Group and Pat Buchanan shouting about quarantines. I remember our “health” class, where the proto-absitence education of choice was mostly touch-feely stuff about fifty ways you could be intimate without sex, laced with strong doses of gender essentialism. (I remember “Guys give love to get sex, girls give sex to get love” being not just something that was discussed but presented as a clear fact about the world. It may have even been an answer on a test. “There’s no condom for the heart” was also a popular one.) I remember a guest “motivational” speaker saying that Magic Johnson would be condemning his wife to death if he slept with her again even once. I remember people saying that 1 out of 50 — or was it 1 out of 10 — kids in college had AIDS and if you slept with anyone it was only a matter of time until you got it.

No one was out in my high school that I was aware of. The only time gay people were mentioned was when someone said “It’s not just gay people who get it” (implication: therefore it matters) or when a certain teacher/coach would tell gay jokes to get the kids on his side. There was a substitute teacher who I guess was effeminate in some way — I only remember the way people talked about him – and he got it even worse than the other substitutes, including from the other teachers. There was nothing about gay rights in our very short history section on Civil Rights. Even though I thought of myself as “political” because I’d gotten interested in Civil Rights and feminism and even tried to organize a little “teach-in” when the first Gulf War happened, I’d never heard of Stonewall or Harvey Milk or ACT-UP. This was at a well-regarded, public suburban high school where people did well on the SATs and everyone went to college. And it wasn’t the South. I got into a lot of political arguments with people that ended with them telling me I shouldn’t take things so seriously. I didn’t know what I was angry about yet, but I knew there was something wrong with a world where the “good schools” expected a loud mouth girl to “do well” and “be smart” but found any actually application of curiosity to the outside world embarrassing and a liability.

Reading about this film made me think about AIDS in those years because of an essay I came across when I was teaching composition in graduate school by Randy Shilts called “Talking AIDS to Death,” a follow up to And The Band Played On, where he talks about the horrible irony of being “successful” with his book while people kept dying. (I can’t seem to find a copy online but there are lots of student essays for sale that quote it and a link to a database that has an abstract and warns that the information in it was accurate in 1989 but “standards may have changed.” To plagiarize Jamaica Kincaid: there’s a world of something in that, but I can’t get into it now.) In the piece he talks about going on Downey’s show, reluctantly after being assured Downey had a brother with AIDS and would be respectful. Once they’re on the air, it’s all quarantines and fuming. Shilts threatens to walk off, only to be told not to worry, Downey had “a fall back position.” Everyone was in on the act, it seems, but the audience.

Shilts didn’t get tested when he was writing And The Band Played On, reportedly because he was afraid it would affect the “objectivity” and reception of the book. It’s an old story: feminists who write about gender, African Americans who write about race are “not objective” or “angry.” Those with less at stake, who wield their real or faked or real but amped up anger for ratings don’t have to worry about such things. The righteous anger of outsiders and people fighting for their lives frightens us: it challenges us. Why aren’t we fighting too, why aren’t we angry? But reactionary anger we’re meant to take in stride: it’s just how people blow off steam. It’s just good TV.

Maybe so. But poking around in the much the way these filmmakers seem to have done or the way David Foster Wallace does never makes good on its promise. It never unmasks some legitimate grievance at the root of all the ugliness. It never says anything useful about some populist way for progressives to talk to “the people.” There’s just one layer of ugliness after another. It’s not without its fascinations. But better to rewatch How to Survive a Plague, reread Shilts or Larry Kramer, and imagine how ridiculous the question of whether they “really meant it” would seem.