Sinjar: Proxy Wars on Sacred Ground

Eleven years ago today, ISIS began its genocidal assault on Iraqi Yazidis. Reporting from the Sinjar region, our correspondent shows how a fractured community finds its path to recovery hindered by geopolitics as much as by violence.

Hanif Khudeda, a Yazidi woman, stands outside of her tent on Mount Sinjar. (Courtesy of Jaclynn Ashly / Jacobin)

Mount Sinjar rises from the arid plains of northwestern Iraq like a grassy sentinel — ancient, scarred, and unyielding.

Today marks eleven years since the Islamic State launched its genocidal assault on the Yazidis in Sinjar.

To the Yazidis, the mountain is sacred; they believe Noah’s ark rested here after the biblical flood. Its slopes are dotted with shrines, sacred places where fires are lit and prayers spoken. Under starlit skies, Yazidi oral histories of creation, exile, and survival are passed down from generation to generation.

Mount Sinjar has also served as a shield for the Yazidis through generations of persecution. The historically marginalized ethnoreligious community, with roots in pre-Zoroastrian belief systems, blended with Sufi influences, has long relied on the mountain for protection.

So when the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), or Daesh — a Salafi-Jihadist group that branded the Yazidis as infidels — stormed the Yazidi heartland of the Sinjar region on August 3, 2014, hundreds of thousands instinctively fled toward the mountain.

While many escaped to Iraq’s Kurdistan Region, an estimated fifty thousand Yazidis took refuge on Mount Sinjar’s upper plateaus.

For those unable to reach higher ground, unimaginable horrors ensued. Within days, ISIS had killed thousands. Nearly seven thousand Yazidis were kidnapped — women and girls sold into sexual slavery, boys indoctrinated as child soldiers. Over a thousand Yazidis, mostly children and the elderly, died from starvation, dehydration, or injuries during ISIS’s siege of Mount Sinjar, which cut off tens of thousands from food, water, and medical care.

The entire Yazidi community of around four hundred thousand was displaced, captured, or killed.

Over a decade after ISIS’s genocidal assault, a fragile calm has returned to Mount Sinjar, interrupted occasionally by Turkish drone strikes targeting Yazidi militias aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), a Kurdish militant group that has waged a decades-long insurgency against Turkey. However, following PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan’s recent call for disarmament, such strikes have grown less frequent.

Threaded between military posts, checkpoints, and tunnel entrances etched into the mountainside, rows of makeshift tents stretch along Mount Sinjar’s northern edge. Hundreds of Yazidi families remain here, unwilling to return to villages below where the past feels perilously close.

Most have stayed on the mountain since ISIS’s initial onslaught; others returned after years in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in the Kurdistan region, where over two hundred thousand Yazidis still live. All are drawn to the mountain as their last true protector against a genocide they fear may yet return.

ISIS no longer holds Sinjar, but the district is now split between armed groups backed by outside powers. Caught between rival militias — and sometimes compelled to join them — Yazidis remain in limbo. Their future in Sinjar is uncertain and shaped by forces beyond their control.

Exodus

Layla Junde, a forty-one-year-old mother of eleven now living in a mountain tent, remembers the moment she fled her village in southern Sinjar. A relative had rushed back from the market with a chilling warning: black flags were advancing.

“Our whole family got in a truck and headed for the mountain, picking up other Yazidis along the way,” Junde recalls. At a Kurdish Peshmerga checkpoint, soldiers insisted they were safe and protected — urging them to turn back. But the family ignored the assurances and pressed on to the mountain, a decision that likely saved their lives.

At the time, the Peshmerga — loyal to the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and dominant in Sinjar — abruptly withdrew as ISIS advanced, leaving thousands of Yazidis exposed. Some who trusted the Peshmerga and returned home were trapped when ISIS cut off escape routes.

A desperate, chaotic exodus unfolded as Yazidis fled en masse to Mount Sinjar. At its base, Junde and her family abandoned their vehicle, joining thousands scrambling up steep, winding paths on foot. The air filled with cries of terrified children, infants cradled in arms or strapped to backs.

“It was very, very difficult,” recalls Junde, who was eight months pregnant and caring for three small children. “But the thought of what ISIS would do to us if they caught up kept me moving, even when I felt like collapsing.” Gunfire and rumbling vehicles pushed her to climb faster.

Junde walked for hours under the scorching 104°F sun, without food or water, desperately to reach the high plateaus. Other Yazidis walked for days, but the journey was too arduous for the elderly, sick, and disabled. Faced with an impossible choice, many families left vulnerable loved ones — on roadsides, in abandoned homes —to save their children.

ISIS soon besieged the mountain from all sides, leaving tens of thousands of Yazidis scattered across jagged outcrops or dry plateaus under the searing sun, with no shelter or adequate supplies. “There was no food, no water, only fear,” Junde remembers. “It was so hot during the day and so cold at night.” A handful of Yazidi civilians, armed only with basic weapons, tried to repel ISIS advances.

“We were just terrified the whole time,” Junde says. “We thought we were going to be killed at any moment if ISIS reached us. We had no idea if help would arrive or if we would be left there to die.”

As hunger deepened and hundreds, especially children and the elderly, succumbed to dehydration and exposure, the humanitarian catastrophe triggered an international response. After several days under siege, the US-led international coalition — a multinational alliance formed to combat ISIS in Iraq and Syria — began air-dropping food, water, and other essential supplies.

About a week into the siege, PKK fighters from Iraq and their Syrian allies, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), intervened. Backed by US airstrikes, they opened a precarious humanitarian corridor into Kurdish-controlled northeastern Syria, allowing tens of thousands of Yazidis to escape. From there, survivors crossed back into Iraq and were settled in displacement camps across the Kurdistan Region.

At least ten thousand Yazidis — including families and volunteer fighters — chose to remain on Mount Sinjar. Many refused to abandon their sacred ancestral land, placing their trust in the mountain alone. Others took up arms in self-defense, joining PKK and YPG fighters to defend their people and reclaim what was taken.

Most were ordinary men and women who had never before held weapons. Trained by the PKK and YPG, they formed local defense forces like the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBŞ) and Yezidxan Security Forces (HSÊ), which would continue the fight from their base on Mount Sinjar.

These PKK-aligned forces were crucial to the 2015 operations to liberate Sinjar. That November, they fought alongside KDP Peshmerga — who returned with US air support — in a joint offensive that successfully recaptured Sinjar city and parts of the central district. Southern areas, however, remained under ISIS control.

The Yazidis were not alone in turning to armed resistance. Nearly two months before ISIS stormed Sinjar, it had already overrun much of Iraq, triggering a near-total collapse of the Iraqi military. In response, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, Iraq’s most influential Shia cleric, issued a landmark fatwa calling for jihad and urging all able-bodied Iraqi men to defend the country.

Sistani’s call mobilized tens of thousands, mostly from Iraq’s Shia majority, to form new militias or join existing ones, including groups backed by Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. In 2014, these forces consolidated under the umbrella of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), or Al-Hashd al-Shaabi.

In 2016, as the Iraqi federal government shifted its focus to retaking Mosul, it deployed PMF units to southern Sinjar. Operating under state command, the PMF provided weapons and training to Yazidi, Sunni, and Shia Arab tribes, helping them to liberate their areas. Their forces cleared key villages and severed ISIS supply lines along the Syrian border — essential to breaking the group’s hold on the region. By 2017, they had retaken all major villages in southern Sinjar, including Kocho — the site of one of the genocide’s worst massacres.

But after the fighting had ended, many of the liberating forces remained. Rather than ushering in recovery, their presence fractured Sinjar into a patchwork of rival authorities. Competing armed groups, each backed by outside powers with divergent agendas, turned the district into a contested and unstable zone.

Sinjar has been disputed territory since the 2003 US invasion, when KDP Peshmerga first took control. It has now also become a transnational conflict hub — a battleground for influence where Iraqi federal forces, Kurdish parties, and foreign-backed militias all stake claims.

What was once a frontline against ISIS is now a geopolitical chessboard. And caught in the middle are the Yazidis — a shattered community still waiting for peace and a future they can call their own.

The Last Safe Ground

Seve Murad is among those who have sworn to never return to the plains below.

“I will never leave this mountain again,” says the 39-year-old mother, her voice soft against the wind. Around her, a patchwork of weathered tents clings to Mount Sinjar’s slopes.

Life in the remnants of this informal settlement of Sardasht — meaning “top of the plain” in Kurdish — is fragile but, to many, still safer than the uncertainty below. The camp formed organically during the ISIS onslaught, as Yazidis who remained on Mount Sinjar gathered along its northern edge. Initially home to some seven hundred families; Sardasht has been declared closed by authorities and stripped of aid. Yet at least three hundred families remain in these dilapidated tents, according to Yazidi activist Ali Shamo.

For years, Murad kept her seven children safe from the atrocities unfolding beyond the mountain’s protective embrace. In 2020, she heard her home in the southern village of Tilazer was still standing — a rare glimmer of hope given that, even in the town of Sinjar, 80 percent of public infrastructure and 70 percent of homes were destroyed. The devastation in the south was even worse.

“I felt some hope,” Murad says. “I thought maybe we could return.” She sent her eighteen-year-old son and his sixteen-year-old cousin to check. They found the house intact — but when they stepped inside, an IED exploded, killing them both.

ISIS, in retreat, had booby-trapped Yazidi homes and villages with improvised explosives — hidden in doorways, furniture, and fields — to terrorize returnees and sabotage resettlement. Large stretches of Sinjar, especially the south, remain contaminated with IEDs, claiming lives and stalling reconstruction.

“ISIS is gone from here,” Murad says softly, “but still, they killed my son.”

Nearly all displaced Yazidis in Sardasht camp are from southern villages — areas that bore the brunt of ISIS atrocities and remain in ruins. While parts of the north have seen modest recovery, Sinjar’s old town remains in ruins, and the south is almost entirely destroyed.

This sluggish reconstruction is due to deep-rooted political and security challenges. As a disputed territory, Sinjar suffers from a governance vacuum. This has led to stalled decision-making, causing delays, mismanagement, and inadequate funding for reconstruction. Recent US aid cuts have made matters worse, deepening the crisis for displaced communities.

For the Yazidis in this mountain camp, fear is the thread that binds them.

Often, the decision not to return to their villages stems not just from physical destruction, but from lingering trauma — and deep mistrust of former neighbors and of both the Iraqi government’s and KRG’s ability to guarantee their safety.

“If you built me the most beautiful mansion in my village, I would still not go back,” barks 50-year-old Hanif Khudeda. “It’s only a matter of time before the Muslims attack us again.”

During the genocide, some local Sunni Arab — and even Kurdish — tribes were accused of directly aiding ISIS: looting abandoned Yazidi homes, helping traffic women and girls into slavery, and participating in mass killings. Survivors recount neighbors luring Yazidis into false promises of protection, only to betray them to ISIS. For Khudeda, this complicity has severed any possibility of coexistence.

She was among the tens of thousands who escaped the mountain siege through the humanitarian corridor into Syria nearly eleven years ago. Like countless others, she spent years in IDP camps across the Kurdistan Region. She returned to Mount Sinjar in 2017, settling in Sardasht camp — one of about 30 families who made the same journey back to the mountain, says Shamo.

Inside her tent, Khudeda, a mother of twelve, sweeps a concrete slab laid over packed earth. Her grandchildren dart around, laughing and leaping out of the broom’s path. “I didn’t feel safe in the camps either,” she says. “There is no safe place for Yazidis in Iraq. Another genocide will happen — I’m sure of it. And when it does, everyone will flee to the mountains again.”

She pauses, then adds: “I might as well get a head start.”

Shifting Frontlines

Even after ISIS’s guns fell silent, Mount Sinjar wears a fractured face, its contours carved by rival — and sometimes cooperating — armed factions. From its slopes to the plains below, the mountain is etched with competing claims. Yazidis are both caught in the crossfire and embedded in the ranks of these competing forces.

At the northern edge of Mount Sinjar, members of the YJÊ, the YBŞ’s all-female unit, guard a checkpoint beside an empty playground perched atop a vital tunnel hub. The playground is placed deliberately, in hopes of deterring Turkish airstrikes on the infrastructure beneath. Higher up, raw gashes mark other tunnel mouths — part of a sprawling underground network extending across the Syrian border.

YBŞ and allied Yazidi militias have spent years constructing a tunnel network to bypass Iraq’s fortified border barrier — which includes high walls, trenches, barbed wire, and watchtowers — allowing them to continue moving weapons, fuel, and supplies to and from their Syrian partners.

The YBŞ and affiliates control much of the mountain’s northern terrain, including Sardasht camp and these border smuggling corridors. They also hold territory in other northern areas and maintain a presence in Sinjar town.

Formally integrated into Iraq’s armed forces in 2016, PMF units, including Yazidi-led brigades, are concentrated south of Mount Sinjar, controlling much of the territory. Iraqi federal forces are also present, securing key checkpoints around Sinjar town.

The KDP Peshmerga, with thousands of Yazidis in its ranks, once held positions on Mount Sinjar and across the broader district. But in 2017, their fragile alliance with PKK-aligned Yazidi militias unraveled and turned to armed clashes. Despite shared Kurdish identity, KDP and PKK are bitter rivals. The PKK, which promotes democratic confederalism, sees the KDP as aligned with Turkey, while the KDP advocates for a conservative, ethnonationalist Kurdish state.

Later that year, in the wake of the Kurdish independence referendum, the Peshmerga were further pushed out by Iraqi federal forces and PMF units. A power vacuum followed — and PKK-aligned groups, backed by certain PMF factions seeking to limit KDP influence, moved in. With political and security cover from the PMF, these groups established a de facto administration across parts of the district, particularly on and around Mount Sinjar, modeled on the PKK’s vision of democratic confederalism. Their governance has not received formal recognition.

Despite ideological differences, PMF and PKK-aligned groups forged a pragmatic alliance in Sinjar, driven by overlapping strategic interests. Chief among these is access to Syria: for Iran-aligned PMF factions, Sinjar offers a vital land corridor to Syria and Lebanon; for PKK and affiliates, the area links strongholds in Iraq to allies in northeast Syria. Both camps also oppose Turkish influence and view the KDP as a mutual rival.

As a consequence of these strategic entanglements, Yazidis are caught in regional power struggles far removed from their own interests. Their association with PKK has drawn Turkish drone strikes, forcing families to flee again. The presence of Iran-aligned PMF factions risks embroiling Sinjar in broader geopolitical conflict — with some suggesting the area could serve as a launch point for missiles targeting Israel.

“The Yazidis are a small community that just survived a genocide,” says Murad Ismael, a prominent Yazidi activist, co-founder of the educational initiative Sinjar Academy, and former director of Yazda, a global Yazidi rights group.

They are not looking for problems with Turkey and they are certainly not wanting to go to war with Israel or the United States. It’s not going to serve Yazidi interests to get involved in complicated regional conflicts. In general, the Yazidis want peace, security, and protection from genocide.

“But they are just being exploited in every direction,” he adds.

Sinjar’s Armed Peace

Although segments of YBŞ were formally incorporated into the PMF, tensions persist. In 2022, a government-led operation to remove YBŞ fighters — part of the stalled 2020 Sinjar Agreement, which called for the withdrawal of non-state armed groups — triggered clashes with the Iraqi army, forcing thousands to flee again. The PMF played a key role in de-escalating and brokering a fragile truce.

According to Ismael, in Sinjar’s contested terrain, local and personal interests often eclipse larger political goals. “There’s very little strategic thinking in all of this,” he says. “It’s mostly about low-level interests — smuggling, making money.” Control over key smuggling routes is a primary concern for armed groups, offering a steady source of income through informal taxation to fund operations and pay fighters.

Most Yazidi fighters, Ismael adds, are not driven by ideology or regional agendas, but by personal trauma following the genocide or the need for economic survival. As a result, Yazidis are fragmented across competing armed factions.

“Turkey could drop a bomb on us at any moment,” says Junde, a resident of the Sardasht camp. “But I feel safer with the [PKK-aligned] YBŞ because they are locals. They saved us from ISIS when everyone else abandoned us. If ISIS comes again, the YBŞ won’t run.”

While the PKK helped train Yazidi fighters, their political ideology has not found deep roots in the community, according to Ismael. “Their ideologies and regional interests are not easy things for the Yazidis to buy into,” he says. “But they trained the Yazidis in their fight against ISIS, and they have common enemies, particularly the jihadists.”

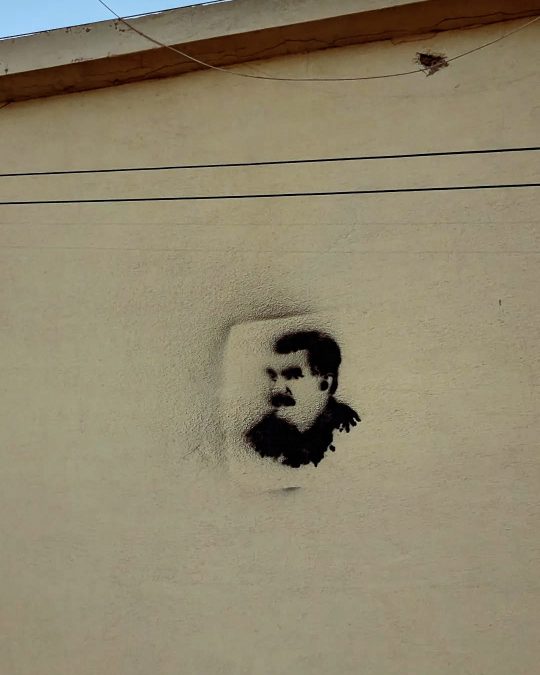

In northern Sinjar, PKK propaganda seems to have found traction —Öcalan’s face is spray-painted on village walls, and posters of Yazidi fighters killed in Turkish airstrikes line the road to YBŞ checkpoints, linking their struggle to the PKK’s broader war. Other Yazidis, however, resent PKK, viewing them as external actors bringing conflict.

Thousands of Yazidis joined the PMF, despite its dominant Shia factions and alignment with Iran. “Many Yazidis are strongly anti-KDP because they are still angry over them abandoning them in 2014 and blame them for the genocide,” Ismael explains. “So, if you reject the PKK’s ideologies but hate the KDP, the PMF becomes a good alternative because they are also against the KDP.”

“The PMF has also really worked on exploiting that sentiment to get the Yazidis to join their ranks,” he adds.

For many Yazidis, joining an armed group is less about emotions than economic survival. “Mainly it’s about resources,” says Michael Knights, a senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “The PMF, for instance, offers government salaries and pensions — and for Iraqis, nothing is more important than a pension.”

Thousands of Yazidis are enlisted with KDP Peshmerga; many are also in the Iraqi army or federal police. “There are probably around thirty thousand Yazidis involved in some kind of armed force,” estimates Ismael. “That’s a huge number for a community this small. And most signed up because the Iraqi economy left them with no other lifeline.”

In the wreckage ISIS left behind, armed groups offered protection — and paychecks — fracturing Yazidi society in the process.

Recent developments in Syria and within the PKK further threaten to reshape Sinjar’s fragile balance. The late 2024 overthrow of Bashar al-Assad by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) — a former al-Qaeda affiliate led by Ahmad al-Sharaa — has sparked alarm. Sharaa’s new government includes figures linked to the sexual enslavement of Yazidis, stoking fears among Yazidis of renewed jihadist threats. The rise of HTS has also unsettled Iran-backed PMF factions.

Meanwhile, the future of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), dominated by the PKK-aligned YPG, hangs in the balance. For YBŞ in Sinjar, which depends on SDF-linked supply routes, any weakening of the Kurdish position in Syria could be destabilizing.

The situation grew more complex after PKK leader Öcalan called for disarmament and the group’s formal dissolution. SDF leadership insists this does not apply to forces in Syria, and experts say YBŞ and other Yazidi militias are unlikely to disarm.

“They got some support from the PKK, but the YBŞ was never deeply tied to its broader struggle,” says Knights. “They might retain habits like rank structure, but most aren’t long-term Öcalan supporters or fully committed to PKK ideology.” A YBŞ commander recently confirmed that the group would remain active to protect Yazidis.

Still, concerns persist. “Any weakening of the SDF and PKK will inevitably erode the YBŞ’s strength,” says Ismael, who expects PMF factions to strengthen their alliance with YBŞ — particularly in response to Syria’s new leadership, which includes former al-Qaeda figures implicated in Yazidi persecution.

“Yazidis Have to Come Home”

While some worry that the proliferation of Yazidi fighters across rival armed groups could sow internal discord, Ismael sees a strategic advantage in this fragmentation. For a community shaped by genocide, he says, the priority is survival.

“Our perspective is different,” Ismael explains. “We’re not thinking like state actors. We’re thinking like survivors. In a country as unstable as Iraq, anyone who can offer us protection is welcome.”

Though none of the armed forces in Sinjar fully represent Yazidi interests, Ismael believes the community’s involvement across all of them strengthens security. “Every one of these groups answers to someone else,” he says. “But they also now have Yazidis among them. That means if there’s a threat, those fighters won’t abandon their people — they’ll defend their communities and families.”

Rather than placing all hope in a single militia, dispersing across forces gives Yazidis political leverage and military insurance. “It’s a form of resilience,” he says. “In Iraq, no one keeps their loyalty in just one basket. Why should we?”

“The PUK [Kurdish rivals to the KDP] works with Iran. The KDP is with Turkey. The Shia with Iran. The Sunnis with Qatar and Turkey. Every group plays the game. And Yazidis are learning to play it, too.”

The result, he says, is a population better positioned to defend itself. “What happened to us in 2014 would be much harder to repeat today.”

“I really don’t expect Iraq to be flourishing economically or culturally any time soon,” he adds. “I really simply want Yazidis — for now — to not face another genocide.”

Despite their fractured resilience, Yazidis face a deeply uncertain future. Ongoing insecurity and stalled reconstruction have left most confined to displacement camps — unable or too afraid to return home.

Many saw the presence of international bodies like UNITAD — the UN Investigative Team tasked with collecting evidence of ISIS crimes, including the genocide against Yazidis — as protection. But with UNITAD’s abrupt closure last year and aid cuts forcing humanitarian organizations to scale back or shut down, Yazidis feel abandoned.

Life in the tent settlement on Mount Sinjar remains a struggle. Most residents survive on sporadic labor and have gone years without aid. With only one primary school on the mountain, many Yazidi children are not continuing their studies. Across Sinjar, education is also severely limited.

“Whenever Yazidis have faced atrocities in our history, we have always responded by isolating ourselves,” Ismael explains. “But in 2014, we paid a heavy price for that. We were disconnected from the world — we lacked education, we didn’t understand geopolitics, and we had no means to defend ourselves.”

He fears history is repeating. “This genocide is pushing us back into isolation. Many Yazidi children are out of school because families are prioritizing safety. But that will cost the next generation dearly.”

Disillusionment is growing, and with it, a desire to flee. “A lot of Yazidis have lost their connection to the land, the nation, everything,” Ismael says. “Most no longer see a future here. When they think about the future, they dream of leaving Iraq altogether.”

Yet for Ismael, returning to Sinjar remains the only path to survival. “I don’t know how we will make it through all of this,” he says. “But I know one thing: Yazidis have to come home. We may not resolve the security situation or all these competing interests anytime soon. But the one thing that is in Yazidi interest is returning to Sinjar and rebuilding —so it can be home again.”

Back at her tent, Murad fights tears. “I feel his absence every day,” she says, speaking of her son, who was killed by an IED years ago. “I shouldn’t have let him leave the mountain.”

“For the Yazidis, there is only fear — no hope,” she says.

Like thousands still sheltering on the mountain, Murad lives in harsh limbo — caught between temporary refuge and permanent displacement. “We live in between genocides,” she says softly. “The genocide we have already endured and the genocide we fear is still coming.”

Her eyes, wet with tears, fix on the mountain’s ridgelines. “But at least Mount Sinjar still stands,” she says. “It’s the only thing that I know won’t abandon us.”