Trump’s Venezuela Actions Are About More Than Oil

Venezuela’s heavy crude is expensive to extract, it will take years of sustained investment to meaningfully lift output, and it may not even be profitable at current prices. The current aggression is more about power than economics.

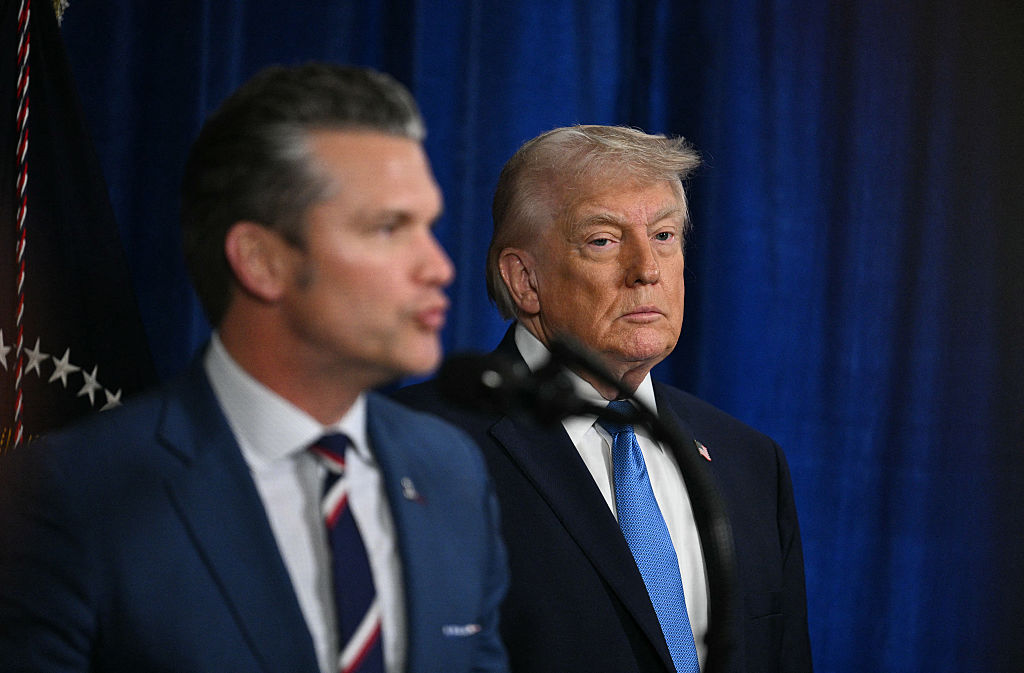

Donald Trump has contradictory goals of solving “affordability” problems by bringing the price of gasoline down and his desire to “drill baby drill.” (Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images)

After the brazen US invasion of Venezuela and removal of Nicolás Maduro from office, many on the Left have settled on a basic explanation: it’s all about the oil. Such an explanation relies on a familiar Marxist “instrumentalist” theory of the capitalist state that its primary role is to do the bidding of the capitalist class.

Certainly, the first and second Trump administration’s extreme deregulation of the oil and gas industry has not dissuaded many from this kind of interpretation. And, of course, in his press conference after the invasion, Donald Trump himself said the operation was indeed all about the oil. So this case appears to be closed. Yet if you actually inspect the political economy of the oil industry, the oil explanation starts to make less and less sense.

Is Venezuela’s Oil Even Profitable to Produce?

Oil markets work through commodity cycles of boom and bust. When prices are high, oil capital is keen on investing in new drilling. When prices are low, less so. While the current price level is somewhere in between (currently trading at $56/barrel and falling), prices are overall depressed, and have been for most of the last decade (apart from the boom associated with the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022).

Given Venezuela’s “heavy” bituminous crude oil is very difficult and costly to extract, I suspect it might not even be profitable to produce with oil prices below $60/barrel. A break-even price for Venezuelan oil is difficult to find, likely because of data problems, but it’s worth noting one industry estimate for the very similar Canadian oil sands is $65/barrel.

You’ve probably heard that Venezuela has the largest “proven reserves” in the world — but note that category hinges on whether or not the “reserves” are economical to produce (and it’s not clear they are).

Therefore, apart from Chevron, who already has much capital sunk into Venezuela, there will not be much interest among the major US oil companies to invest in new drilling. In fact, as this has become more clear, Trump even floated the idea that US oil companies could get “reimbursed” for their investments. I wonder how the US Congress will approach the idea of US taxpayers paying for the reconstruction of Venezuela’s dilapidated oil sector? What is more disturbing is how Trump’s “gangster imperialist” ploy will affect Chinese companies who have already invested some $2.1 billion since 2016.

This all said, there are some fractions of capital apart from the major oil companies who might have some interest in profiting off this invasion. Certainly the share prices of many oil firms have increased, but my reading is that this is based on the expectation they may now receive compensation for expropriated property and investments in the wave of nationalizations in the 1970s and again under Hugo Chávez in the 2000s.

There is also interest among some financial firms like hedge funds — particularly because of Venezuela’s distressed debt situation — but these companies aim to profit off existing assets and debts, not embark on major new investments in oil production.

It is also clear some US refiners can make use of Venezuela’s heavy oil. But these refiners already had plenty of that oil from the Canadian oil sands. The entrance of Venezuelan heavy crude into this market might reduce the price such refiners pay by a few dollars, but this is not a game changer for their profitability.

Unleashing Venezuelan Oil Threatens US Production

There has been much discussion of Trump’s contradictory goals of solving “affordability” problems by bringing the price of gasoline down (it is down, for what its worth) and his desire to “drill baby drill” in the United States. It is also well known that shale producers in the United States use high-cost and complex hydraulic fracturing techniques, and thus need high prices to remain profitable. To “drill baby drill,” Statista gives estimates of a variety of shale plays in the United States — and all require prices above $60/barrel to break even.

In other words, if Venezuelan production were to increase, it could depress the global oil price further and damage the US oil capitalists (and workers) at the core of the MAGA coalition. Yet, again, I’m skeptical oil production will increase in Venezuela anytime soon anyway.

One of the sharpest insights on the political economy of oil comes from the leftist collective Retort and their 2005 book, Afflicted Powers: “The history of twentieth-century oil is not the history of shortfall and inflation, but of the constant menace . . . of excess capacity and falling prices, of surplus and glut.”

Originally, this menace was combatted by a capitalist cartel — the “Seven Sisters” oil companies — who carefully divided oil production and markets among themselves on a global scale, but this role was subsequently taken up by countries of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) interested in maintaining high prices that translate into high rents/taxes. Regardless, despite popular narratives, the oil industry is not always chomping at the bit to extract any and all oil.

As Timothy Mitchell argues, oil companies’ more keen interest is in maintaining and reproducing the scarcity needed to keep prices high enough for profitable accumulation. In the context of depressed prices today, they would be far more interested in pumping the oil they have and recouping previous investments, as opposed to drilling new wells.

“Political Risk”

The other key factor here that is likely to dissuade oil companies from investing is “political risk.” Mining and oil companies in particular much prefer to invest in countries where the political and legal situation is stable and, hopefully, favorable to private investors (i.e., low royalty and tax rates). Obviously, that is not the case in Venezuela since it is literally not clear who is in charge at the moment.

Raymond Vernon’s 1971 Sovereignty at Bay: The Multinational Spread of U.S. Enterprises articulates a powerful theory of the “obsolescing bargain”: when prices are low, extractive enterprises have leverage and can make favorable deals with low royalty and tax rates in host countries. However, when prices (inevitably) rise, the “bargain” becomes obsolete, and host countries can renege on their previous agreements, raise royalty and tax rates, or, even, expropriate them altogether. This is indeed what we could say happened with Chavez in the 2000s — a left-wing socialist environment combined with an oil price boom.

Regardless, if oil companies were going to invest in Venezuela on favorable terms today, there would need to be much more certainty on the political situation. For that, I suppose we will wait and see. One caveat to this analysis, is the question of whether Trump himself will grease the wheels of investment (make it clear to specific companies that investing in Venezuelan oil will yield other political favors). It’s possible, but the historical record of oil capital’s reticent investment patterns during low price periods will be a lot to overcome (especially in the degraded infrastructural context of Venezuela).

The Absolute Autonomy of the State

We should push back against an overly “instrumentalist” account of the capitalist state where this invasion was undertaken on behalf of US oil capital. Adam Tooze’s description that Trump is more interested in “feckless reality TV Cosplay resource imperialism” seems much more closer to the mark. The fact that after the invasion, the White House posted a meme with the term “FAFO” (“Fuck Around and Find Out”) illustrates how interested he and the administration are in the depraved theatrics of it all.

While it does seem clear that this invasion fits into a coherent strategy on the part of the Trump administration to assert domination over North and South America (with Cuba and Greenland perhaps up next, the State Department also posted a meme, menacingly, claiming, “This is Our Hemisphere”), what is not clear is how the interests of capital, let alone oil capital, fit into this neo-imperialist agenda.

If I had to guess, I wouldn’t be surprised if no oil company executives or investors were directly pushing for this invasion. Marxist state theorists talk a lot about the “relative autonomy” of the state, but Trump’s form of narcissism-as-governance really does raise the question of whether or not we’re talking about the absolute autonomy of the state. This is not the first time where this administration appears to be acting in ways that do not align with what one might imagine as the executive committee of the bourgeoisie. What this means for global capitalism at large, and the centrality of the American empire in overseeing it, is really unclear and up for grabs.