Silicon Valley’s Latest Dubious Offering: Designer Babies

Tech capitalists are now marketing the ability to customize your baby’s inherited traits. The process is currently unable to deliver on its promises — but it raises serious concerns about the prospect of genetically encoding inequality.

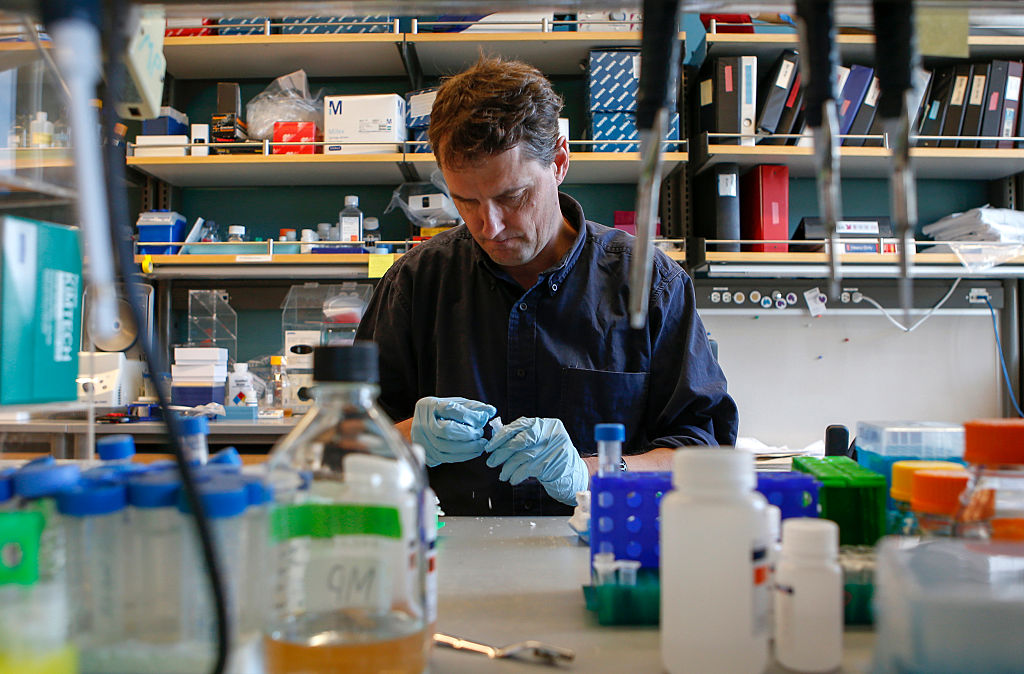

The tech elite’s latest craze is companies that purport to allow parents to genetically customize their offspring. The technology is not ready for prime time, but its emergence raises troubling moral questions. (John Green / Bay Area News Group / Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

Riders of the New York City subway were startled recently by an ad campaign commissioned by a newly established reproductive technology company inviting potential customers to “have your best baby.” The company, Nucleus Genomics, suggested in the “outrage-bait” campaign that, using their service, riders might be able to determine the height and intelligence of their future offspring, among other things.

Such bold promises raise a number of questions, not the least of which is: “Is this not taboo anymore?” The long-reviled effort to improve the genetics of future generations, commonly referred to as eugenics, appears to be experiencing a revival of sorts. Only this time, it is being pitched, in the words of one of its promoters, as a “liberal eugenics.” In contrast to the coercive eugenics of the past that limited the reproductive autonomy of oppressed groups, today’s liberal version is merely supposed to assist future parents in bettering the life chances of their own progeny.

A further question is whether the degree of control over the traits of one’s children that Nucleus suggests it can achieve is even possible. The answer is: as of now, not really. The technology that Nucleus and a bevy of other similar companies use, polygenic embryo screening (PES), allows couples to select among the embryos they’ve produced according to different ratings that the companies provide. But the technology, according to numerous experts, has not yet shown the ability to deliver on the vision suggested in Nucleus’s campaign.

Regardless of PES’s present capabilities and how the technology matures, it does raise a number of ethical dilemmas entangled with the nature of human trait selection. Should this technology ever significantly advance or achieve widespread adoption, it will prove to be more than just a controversial curiosity.

From Mono to Poly

Clinicians can only employ PES if they have ready access to embryos, so this technique is only available for potential pregnancies utilizing in vitro fertilization (IVF). In a nutshell, PES allows potential parents to select which of their candidate embryos, according to characteristics reported by PES, would be the ideal embryo to use for a pregnancy.

PES in principle represents an advance in sophistication over (and is complementary to) monogenic embryo screening, which only looks at well-known individual genes for problematic mutations. Embryos extracted via IVF are often tested for concerning mutations in a variety of particular genes. Mutations in the CFTR gene, for instance, can increase the risk of cystic fibrosis; mutations in the BRCA1 gene can raise one’s risk of developing breast cancer. But monogenic embryo screening is unable to detect a predisposition to diseases that are caused by mutations in more than one gene. PES, by contrast, examines various combinations of multiple genes for problematic mutations.

The ailments that PES screens for are based on polygenic conditions — such as type 2 diabetes or coronary artery disease — identified in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). These are studies that are based on large databases of genomes contributed by volunteers that have been created in the last decade. Essentially, these studies analyze DNA sequences from many who have a certain disease and compare them to DNA sequences of people who do not have it to attempt to discover genetic variants that correlate with a higher chance of developing the condition. Based on the data from these studies, each embryo utilizing PES can be assigned a polygenic risk score (PRS) per condition, a measure of the risk of developing that condition.

The wager from PES’s promoters is that, as genomic databases become more expansive and, in turn, GWAS are able to identify more polygenic correlations with a higher degree of accuracy, the utility of PES will greatly increase.

Not Everyone Can Have Superbabies

PES does not have that many users yet, if only because IVF accounts for only 2 percent of all births in the United States. Additionally, the cost, at $2,500 per screened embryo (over and above base IVF costs), will no doubt limit adoption. Although there are no comprehensive statistics, it seems that, following the first PES birth in 2020, couples that have used PES number in the hundreds. Many of the early adopters of PES have come from the circles of the pronatalist tech elite.

Shivon Zilis, the mother of four of Elon Musk’s children, has reportedly used the PES services of the company Orchid for at least one of her babies. The flamboyant pronatalists Simone and Malcolm Collins used the company Genomic Prediction, a firm backed by OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, to score their embryos for intelligence as well as risk of schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s, depression, and anxiety. A writer from the San Francisco Standard reported attending a “cocktail hour at a venture capitalist’s Presidio mansion” where the Orchid-using investor plucked his baby from his wife’s arms and declared, “Here’s my superrrrrbabyyy.”

Some of PES’s backers envision the technology as a component part of a grander scheme of human advancement, or even transcendence of humanity itself. The CEO of cryptocurrency company Coinbase, Brian Armstrong, who was an early investor in Orchid, conceptualizes PES as only one part of a “gattaca stack” of reproductive technologies including gene editing and artificial wombs. The venture capitalist and occasional eschatologist Peter Thiel has funded the intelligence-screening PES company Nucleus and previously gave a $100,000 grant to Noor Siddiqui, Orchid’s founder.

Not Precisely Snake Oil

PES companies ideally would prefer to offer clients the ability to select among their available embryos on the basis of certain guaranteed characteristics that those embryos would develop as persons. However, there are a number of technical issues with PES that presently prevent it from fulfilling this ideal.

One set of problems comes from the nature of the GWAS studies that identify polygenic traits. The genomic samples on which these databases are built are mainly derived from certain populations, and generating polygenic risk scores for those outside these groups may reduce the accuracy of embryo scoring.

Another concern relates to the fact that a certain set of genes may have not only the effect that a certain PES program is primed to look for, but another set of (perhaps beneficial or detrimental) effects as well — a phenomenon called pleiotropy. Yet another issue is that it will be hard to determine if the PES interventions have worked or not, given that many of the ailments it targets sometimes take decades after birth to manifest.

Then there is a more fundamental question about how statistically predictive PES can even be. The emergence of disease is not exclusively determined by one’s genetics but also by environmental and lifestyle factors. Even in the case of monogenic ailments, a high risk score is not a guarantee of developing the disease but only a probabilistic indicator. PES companies may not be inclined to accurately present modest-to-negligible differences in scoring between embryos, as it might lead a potential customer to question the value of the service.

The absence of regulation in this space has resulted in a lack of standardized methods to produce embryo scoring. The aforementioned San Francisco Standard reporter submitted her own DNA to Nucleus and Orchid and received wildly different scores from each, and even from the same company when it ran analyses at different times. Moreover, Orchid uses a controversial technique called amplification to create an entire genome from a small embryo cell sample for analysis.

Experts have criticized the offerings of PES companies as “unproven,” “not ready for prime time,” and even “snake oil,” and opined that those who have purchased their products have “wasted money.” While it is true that this is not a Theranos-style situation in which the underlying science is a complete fabrication, it is safe to say that the PES companies’ ambitions well exceed their current capabilities. Whether the two will ever converge is uncertain.

Make My Baby Beautiful

If the technology behind PES ever does become as powerful as its advocates hope, that will pose some clear ethical dilemmas. Those able to afford PES would be able to pass on benefits to their children not just in terms of financial resources but in terms of advantageous genetic traits as well. Assuming only the wealthier segments of society were able to access PES, this would widen the inequalities between rich and poor and, what’s worse, encode them at the genetic level. At the extreme, this could create the kind of dystopia portrayed in the movie Gattaca: a two-tier society in which an unenhanced underclass is dominated by their genetic superiors.

Then there are dilemmas surrounding the particular traits that are selected against or selected for. The ability of PES to eliminate traits regarded as undesirable may increase the stigma against people with those traits. On the other hand, there may be some traits — such as the “dark triad” traits of machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy one PES company CEO speculated about providing a score for — which, if selected for, might for obvious reasons have negative consequences for the broader society.

There are a number of future directions in which PES technology might potentially develop. One possibility is that it does not advance significantly, such that it remains a relatively inaccessible and unimpactful vanity project for well-heeled technologists. More concerning possibilities will arise if PES becomes more widespread and/or more powerful. If the former occurs, the broader public may be tempted, or even pressured, to purchase a service that remains confusing, opaque, and of dubious value. If the latter possibility materializes, the ethical dilemmas involving PES will become more urgent.

Compounding these dilemmas, there is an additional technology now being explored, gene editing, which would potentially enable parents not just to select from their existing embryos but insert arbitrary traits into their IVF embryos. Fortunately, this practice is banned in the United States, but gene-editing companies are exploring jurisdictions where they might be able to use it to deliver a bona fide designer baby.

There is an obvious need for regulation in this space, to harmonize the presently inconsistent methods of PRS calculation and standardize how these scores are presented to consumers. And it would probably be wise to whitelist a set of approved traits that can be ethically (de)selected in an embryo, as some other countries have already done. In the meantime, those considering the technically and ethically dubious offerings of the PES companies should heed the timeless advice: caveat emptor.