Work, Well-Being, and the Prospect of Job Extinction

Research shows that work shapes not only material life but also identity and community. If AI erases work as we know it, it could also erase the foundations of mass politics.

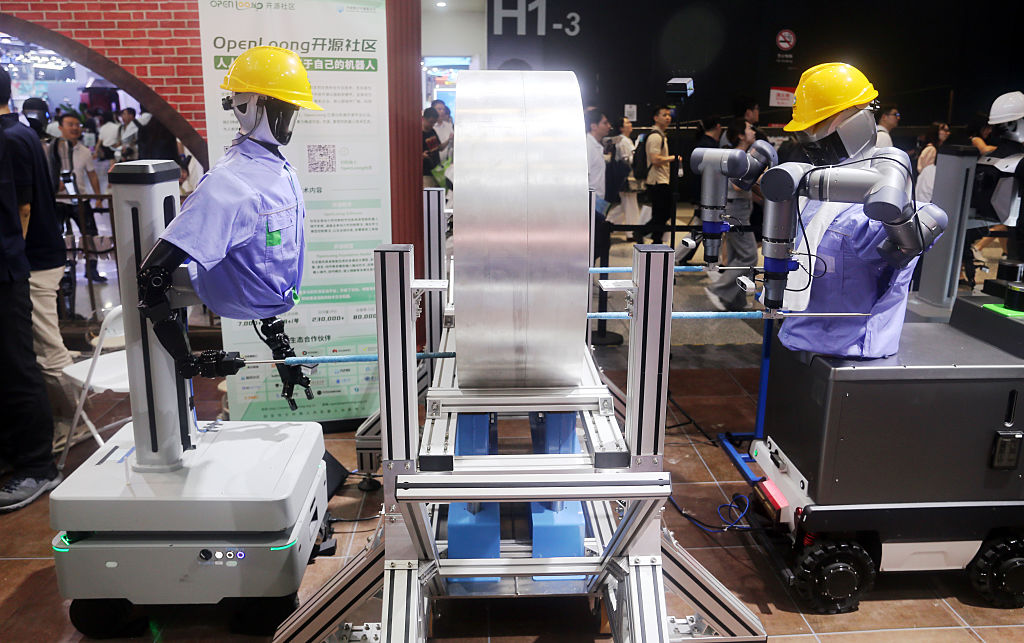

Studies show that in spite of capitalism’s alienation and exploitation, many workers nonetheless derive meaning and connection from what they do. If AI causes work to vanish, labor, the very power needed to resist that fate, could vanish with it. (Costfoto / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

The US economy is facing a downturn characterized by higher prices, lower jobs numbers, and slower economic growth as the consequences of Donald Trump’s global trade war set in. While Trump’s policies break with the neoliberal order and move in the direction of a de facto American mercantilism, his ability to force foreign states to bow to the trade demands of Yankee hegemony are offset by domestic economic troubles and a public exhausted after years of affordability crises and decades of structural inequality. These problems have and will generate plenty of headlines. But there are deeper, long-term threats to contend with.

Economic downturns typically mean job losses and higher unemployment, as current job seekers struggle to find work. The material consequences are significant, often devastating, as workers and families struggle to meet their daily needs, let alone indulge in the small luxuries that they’ve been promised by a marketplace of wonder and abundance.

Beyond these immediate material needs, economies — so often treated as playthings by political and economic elites — also shape communities and the psychological well-being of workers in ways that aren’t directly connected to income. In short, individual well-being is tied, at least in part, to the purpose and sociality that attends work. Economic troubles thus not only cost people money; they cost people community and purpose.

Work Is a Source of Well-Being

In his 2021 study “Unemployment and subjective well-being,” Nicolai Suppa finds “substantial reductions in terms of life satisfaction and mental health, which are associated with unemployment in addition to monetary aspects.” He notes: “These reductions are constant over time, unlike many other adverse experiences. Instead, affective well-being seems to be disturbed only around entering unemployment (if at all). Nonetheless, an emotional toll to unemployment remains.”

The cost of not working, of being unemployed, is persistent, in both a literal and figurative sense. Suppa shows that the hit to well-being actually extends beyond the unemployment period, “irrespective of whether reentering employment or retiring — and far into the distant future as effects can even be observed after years of employment.”

Being unemployed can therefore change not just the immediate material and psychological well-being of workers for the worse, it can be deleterious to the long-term trajectory of their life, bending the curve toward a reduction in well-being. While there is a robust tradition on the Left that dismisses work as such — casting it as inherently alienating, exploitative, drudging, or bullshit — Suppa’s findings, and the broader literature on work and well-being, counsel caution. They remind us that for many, work carries inherent meaning, dignity, and the capacity to connect with others.

Individual jobs and labor arrangements can certainly be alienating, exploitative, drudging, and bullshit, but work itself is not the origin of these conditions; they arise from the way social and economic life is currently organized. Yet despite these conditions, workers still derive meaning, identity, and social connection from work.

Mass Politics Without Workers

Given this dynamic, the future of artificial intelligence as an economic — and employment — “disrupter,” is of concern not just for the material well-being of workers, but their psychological health and the fate of communities, too. As much as we need to be concerned about short- and medium-term economic downturns and job losses because of Trump’s trade war, companies will continue to push for replacing workers with AI regardless.

Estimates of job disruption diverge sharply: Goldman Sachs foresees only a 0.5 percent rise in unemployment, while others warn of a wholesale collapse of white-collar work. Whatever the exact numbers, the one certainty is that work itself is changing — with some studies suggesting that AI-driven automation could put close to half of jobs in advanced economies at risk, including large numbers of blue-collar jobs long thought to be less exposed. All of these outcomes arguably depend less on how fast AI evolves than on whether labor retains the power to shape its deployment.

In theory, cheap labor — which is itself bad for workers — could slow AI adoption by reducing the incentive to replace human jobs, but the long-term appeal of permanently lower labor costs will be too tempting for owners who are thinking five, ten, or twenty years down the line. Two decades from now, there will be global trade. But will there still be accountants? Or, for that matter, mass politics?

The immediate concern with unemployment is meeting material needs, followed closely by the well-being of workers, their families, and their communities. During times of structural transformation, like now, we must also grapple with what these changes mean for labor and democratic political power. For instance, what will it mean for workers’ rights and the balance of power as it relates to law and policymaking if production is managed by AI at scale — especially if the threat of mass politics, like labor action, no longer matters?

And what of the material and psychological fallouts that will attend the shift? Techno-utopians wave away these concerns with promises like universal basic income, but it’s far from obvious that such a solution is plausible. And what of community and individual well-being bound up in work, as it has been for so long?

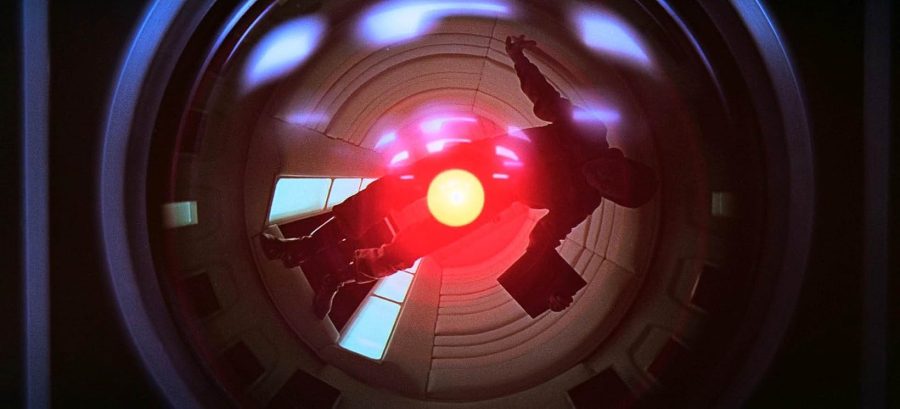

Thanks HAL, but We’ll Decide on the Future of Work

A pause in the development and rollout of AI systems designed to replace workers would allow society to decide collectively what we want from this technology and how to handle the industrial consequences of its deployment. In parallel, state policy at scale will be needed to protect and properly pay workers for the tasks some of them will be required to do to keep societies — and economies — up and running even under heavily automated industries. Such a pause depends on protest, labor action, petitioning, and electoral politics at scale if it is to have any hope of succeeding.

The discussions, debates, programs, and policies that emerge from our collective tackling of the threats AI poses to employment must be grounded in an understanding of what labor has long known and what research confirms: workers know what they need and want, and they know what drives their well-being or undermines it.

Work itself is at the heart of that well-being and of community, which is all the more reason that labor must be protected — just as those who perform it must be adequately paid, kept safe, and treated with dignity and respect.