Private Equity Is Coming for Your Teeth

Private equity firms have been quietly taking control of dental care over the last decade, pushing practices to cut costs and, in some cases, encouraging unnecessary and irreversible procedures.

A dental assistant with her patient in Denver, Colorado, on July 2, 2025. (Hyoung Chang / the Denver Post via Getty Images)

As private equity reshapes American health care, the dentistry industry is now leading the charge — and patients are bearing the cost. In the last decade, private equity firms have been quietly taking control of dental care from behind the scenes, largely through secondary business organizations that push dental practices to cut costs and, in some cases, encourage unnecessary and irreversible dental procedures.

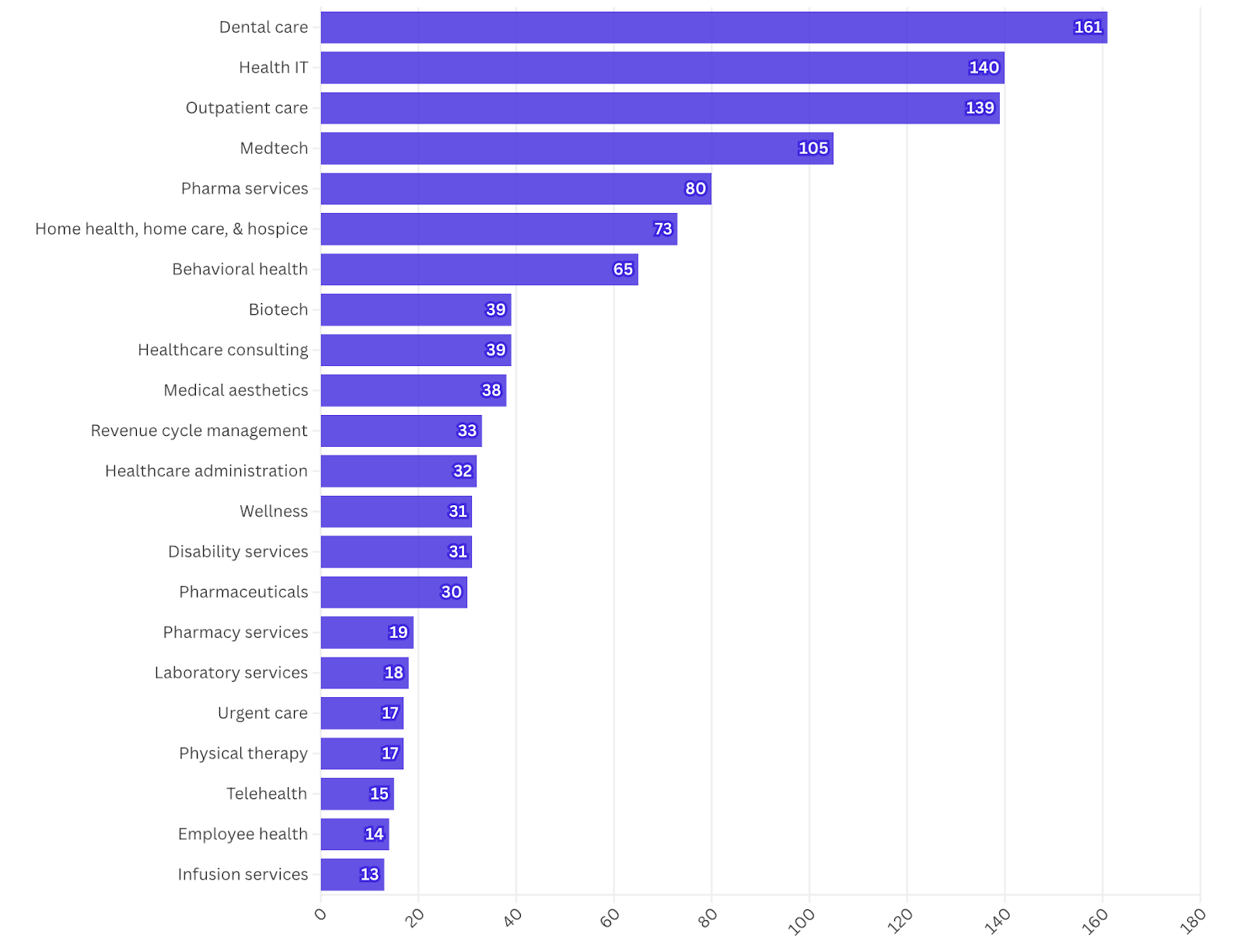

In 2024, the dental industry witnessed 161 private equity deals — the highest number of any health care industry, as tracked by the watchdog organization Private Equity Stakeholder Project. The data reveals that these investment firms are increasingly acquiring dental practices or inserting themselves into clinic management roles, where they then cut corners on patient care.

“A lot of small dental practices have been bought up by big corporations,” said Adelena Brannan, a dental hygienist in Virginia who has been working for twelve years at private practices, where she’s heard about the harmful effects of acquisition. As these large corporations have begun buying up small, independent practices, patients increasingly face overcharging, understaffing, and, in worst-case scenarios, excessive dental treatments that destroy otherwise healthy teeth.

Brannan describes the industry consolidation, along with its focus on cost reduction and speed over quality of care, as “McDonald’s for teeth.”

According to research published last year, the proportion of dentists affiliated with private equity has nearly doubled from 2015 to 2021, reaching almost 13 percent of all practitioners. This consolidation reflects a broader trend: For years, private equity firms have been acquiring thousands of health care businesses worth hundreds of billions of dollars, a move that’s often linked to worse health outcomes — like, for example, at private equity–backed hospitals or nursing homes, where patients are more likely to fall or contract infections.

Private equity firms usually aim to generate large profits over a short period of time by buying a business, cutting costs through measures like layoffs, and eventually selling it to other investors or sending the business into bankruptcy. Critics warn that this opaque, predatory financial industry is pillaging a wide range of American industries from health care and retirement funds to craft stores and Minor League Baseball, leaving economic devastation in its wake.

Notably, private equity has been encroaching on the dentistry field through a growing number of dental service organizations — outside companies that handle the business side of dental practices, such as administrative management, bookkeeping, and marketing services. These organizations, which are ostensibly isolated from clinical work, commonly employ cost-cutting tactics that are harmful to patients, like overbooking and understaffing, to increase profits.

Circumventing the Rules

The dental industry is an especially alluring target for private equity firms because it’s comprised of thousands of independent clinics, offering investors a fragmented industry to consolidate and streamline. Between 2011 and 2019, private equity firms bought up $4.4 billion worth of dental practices.

Most states have regulations in place that seek to ensure medical decisions, including those in dentistry, are made based on patient care, not financial interests. But in the six states without these regulations, including Arizona, Mississippi, North Dakota, New Mexico, Ohio, and Utah, private equity firms can purchase dentistry offices outright.

Most states have regulations in place that seek to ensure medical decisions, including those in dentistry, are made based on patient care, not financial interests. But in the six states without these regulations, including Arizona, Mississippi, North Dakota, New Mexico, Ohio, and Utah, private equity firms can purchase dentistry offices outright.

In the majority of states where licensed dentists must legally own their own practices, investors use dental service organizations to acquire clinics — and circumvent state regulations. These organizations, which were first established in 1975 but began gaining traction in the mid-1990s, only handle business and management operations, leaving dentists responsible for all clinical decisions.

This separation supposedly “creates a firewall between profit-driven decision making and clinical practices,” said Eileen O’Grady, director of programs at the Private Equity Stakeholder Project. But it isn’t always easy to fully delineate between the management side of a dental practice and the clinical operations. “Part of the fear is that when private equity firms own [dental service organizations], they exert undue influence over dental decision-making . . . with an eye to increase profitability and productivity.”

According to a joint 2013 investigation into dental service organizations by the US Senate Finance and Judiciary committees, this fear is warranted. The congressional investigation found that even twelve years ago, these organizations created a system that “places profits before patient care.” Specifically, they showed a “failure to meet quality and compliance standards, including unnecessary treatment on children; improper administration of anesthesia; providing care without proper consent; and overcharging the Medicaid program.”

An example of such abuse comes from the dental service organization Benevis and its affiliated dental chain Kool Smiles, which in 2018 was ordered by the Justice Department to pay nearly $24 million to the federal government and individual states for Medicaid fraud and performing likely unnecessary dental procedures, such as root canals, on children.

A 2020 investigation from Scripps News and USA Today found that private equity–backed North American Dental Group was prescribing root canals to children with healthy teeth as young as three years old in order to get larger Medicaid reimbursements. (Data shows that private equity–backed dental clinics are more likely to accept Medicaid than independent ones.)

In 2022, Kool Smiles made the news again after CBS News found that a two-year-old died just days after he underwent root canals on his baby teeth at one of the chain’s locations in Arizona. In the suit filed against the dental clinic, the family claimed that the dental chain, “overtreats, underperforms and overbills,” and was responsible for their son’s death — though the clinic denied responsibility and the suit was privately settled.

Another investigation by KFF Health News and CBS News last year revealed that dentists at ClearChoice Dental Implant Centers — a dental chain owned by Aspen Dental, one of the largest dental service organizations — were allegedly extracting healthy teeth from patients and replacing them with expensive implants. Experts have warned in various lawsuits against the implant center that this irreversible procedure exposes patients to excessive costs and surgery complications, plus a greater risk of future dental problems like infections and bone loss.

Despite the risks, these aggressive treatment plans, as well as the consolidation of clinics, are highly profitable. Altogether, dental service organizations such as Aspen Dental and Smile Brands, own more than 6,000 locations nationwide, generating billions of dollars in revenue. That income is set to grow, as the global dental service organization market size is expected to reach more than $454 billion by 2030, according to the Virginia-based McGuireWoods law firm, which has legally represented dental service organizations in various capacities.

The majority of these organizations are owned by private equity firms, with twenty-seven of the top thirty dental service organizations run by investment companies as of 2021. Private equity’s influence is particularly prevalent among specialized dental practices, such as oral surgeons and endodontists — likely because specialists earn more for procedures like root canals and implants than general practice dentists do for routine dental exams, leading to more lucrative returns on investment.

“We’re losing private practice dentists fairly quickly,” Helen Hawkey, executive director of the nonprofit PA Coalition for Oral Health, told the Lever. “We’re seeing every year less and less dentists in a private practice where they’re a full owner or part owner, and more and more that are starting to be an employee of another dentist or facility.”

Dentistry’s Wild West

Despite federal investigations and a growing awareness of the industry’s adverse consequences on patient health, current regulations for dental service organizations are scant, and attempts to regulate them have largely failed.

Following the 2013 federal investigation, there have been numerous attempts by states to better regulate these companies. This includes a 2014 rule proposed in Texas that would have barred dentists from contracting with unlicensed entities for nonclinical business services like the ones that dental service organizations provide.

The Association of Dental Support Organizations, which lobbies on behalf of dental service organizations, and the Texas Coalition of Dental Support Organizations strongly opposed this initiative, arguing that an existing state law that prohibits dental practices from operating without a license was sufficient to discourage wrongdoing. The proposed rule was withdrawn from consideration, while a far weaker rule was enacted the following year.

Washington, Georgia, and Virginia also unsuccessfully attempted to pass similar rules limiting the influence of dental service organizations on dental practices in their states. Nationwide, these organizations still remain largely unregulated.

Meanwhile, the Association of Dental Support Organizations has been actively working to “educate policymakers on the benefits [dental service organizations] bring” and counter “opposition based on misconceptions,” according to their website. In the past five years, the association has spent $1.8 million lobbying federal officials on issues including “legislation or regulations that may impact dental service organizations,” according to OpenSecrets, which tracks campaign finances and lobbying.

The American Dental Association, which represents the dental industry, has not explicitly endorsed or opposed dental service organizations. But patient advocates and practitioners are increasingly concerned by the rapid pace at which dental service organizations and profit-motivated business practices are infiltrating the industry.

“I’m terribly concerned. This is not to the patient’s advantage,” said a former dental hygienist who asked not to be named, citing privacy concerns. She and her husband, who was a dentist, operated a clinic for decades and, when they retired, decided not to sell their practice to private investors, despite financial pressures that many dentists face. “You could still make a nice living if you do what’s right for patients, but you make more if you do what’s best for business.”