The Murder of Michael Brown

How regional inequities and a local fiscal crisis conspired to kill Michael Brown two years ago today.

A vigil for Michael Brown in 2014 in Sydney, Australia. earthtoeyes / Flickr

Two years ago today, unarmed black teenager Michael Brown was shot and killed by white police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri. Brown’s death has since become a marker: shorthand for an array of urban and suburban ills, including persistent economic and racial segregation, the racial divide in social and economic opportunities and outcomes, police violence, and the truncated citizen rights of black Americans.

As John Lewis wrote in the wake of Brown’s death, “One group of people in this country can expect the institutions of government to bend in their favor,” but in the “other America,” “children, fathers, mothers, uncles, grandfathers, whole families, and many generations are swept up like rubbish by the hard, unforgiving hand of the law.”

Brown’s death dramatized these stark inequalities. But as the US Department of Justice (DOJ) and local activists and organizations (such as Arch City Defenders and the Organization for Black Struggle) pulled back the veil on policing in Ferguson and St Louis County, other conspirators emerged.

One was fragmented local government: the very fact that a tiny jurisdiction like Ferguson claimed the authority to police Michael Brown at all. Another was the ongoing fiscal crisis in local government, driven by the desire to exercise home rule, absent the capacity to pay for it. In this larger context, the confrontation on August 9, 2014 was as unsurprising as it was tragic.

Over the course of the last generation, shrinking national commitments and haphazard municipal incorporation have pared back public goods and services, while devolving political authority to local jurisdictions that are unwilling or unable to pick up the pieces. “What Washington does to the states,” Jamie Peck observes, “the states do to cities, and cities do to low-income neighborhoods.”

In St Louis County, that burden fell hardest on struggling older suburbs like Ferguson, which responded by using its police department, not just to discipline and control its most vulnerable citizens, but also to extract from them — one busted taillight or jaywalking fine at a time — the revenue that keeps the lights on at City Hall.

Patchwork Metropolis

The jurisdictional fragmentation of the St Louis metropolitan region, which by 2010 sprawled across hundreds of incorporated municipalities and eighteen counties in two states, is both an artifact and a mechanism of racial segregation.

By the middle of the twentieth century, in St Louis, as in other American cities, private discrimination by landlords, home sellers, real estate agents, and lenders had worked hand-in-hand with discrimination backed by the coercive power of the state to construct urban ghettos: over-populated, under-resourced areas in which black Americans, and sometimes members of other marginalized groups, were confined.

Through the middle of the century, the most significant mechanism of ghettoization was the racially restrictive covenant. Legally enforced restrictions written into the deeds of private properties, covenants excluded entire classes of would-be buyers and renters from particular neighborhoods — indeed, from large swaths of the urban landscape. For the excluded, the only viable housing options were in the unrestricted areas of their cities. In St Louis these were concentrated on the north side, where the housing stock was old, physically deteriorated, and far from sufficient to meet demand.

Shelley v. Kraemer, the landmark US Supreme Court decision that ruled racially restrictive covenants unenforceable, grew from a case brought by a white homeowner’s association determined to preserve a North St Louis enclave. In the wake of that decision, the city’s black population expanded into previously all-white North City neighborhoods. Black St Louisans were even able to move to some North County suburbs. But continuing private discrimination kept them out of much of the city and most of the county.

At that time, Ferguson was almost entirely white. But it bordered Kinloch, the oldest black community in Missouri. The municipal boundary dividing Ferguson from Kinloch was secured by a steel barrier that physically blocked access. In the spring of 1968, following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr, hundreds of local activists marched to the barricade, demanding its removal. When Ferguson’s city council voted to dismantle it, local property owners and their alderman temporarily erected a series of new barriers — a wooden board, a “No Trespassing” sign, and a car and truck that blocked the roadway.

Of course, these barriers were just the physical markers of Ferguson’s legal boundary, which, like similar jurisdictional boundaries throughout the region, helped maintain racial and economic segregation. Over the course of the twentieth century, local governments in Missouri — as in most American states — had gained significant authority over zoning, taxation, and public service provision.

Across St Louis County, developers and homeowners took advantage of these new powers to engage in what Charles Tilly calls “opportunity hoarding”: incorporating dozens of new municipalities, passing zoning regulations aimed at excluding unwanted uses — and unwanted people — and gerrymandering local school districts along racial lines.

By the early 1970s, Ferguson occupied a precarious spot in St Louis’s spatial hierarchy. One of the county’s few municipalities to have incorporated in the nineteenth century, its residential stock was older and its lots smaller than those in the sprawling cul-de-sacs sprouting up in the cornfields of West County.

Unlike many other places in postwar suburbia, where multifamily housing was typically prohibited, Ferguson permitted the construction of a series of apartment complexes. Affordable and accessible, it became an early target of working-class white flight from the city and, a generation later, an attractive option for black families leaving places like Kinloch and the city of St Louis.

In 1970, at its peak population of just over 28,000, Ferguson was 99 percent white and just 1 percent black. By 1980, its black population had grown to 14 percent. In 1990 it would reach 25 percent, and by 2000 Ferguson would be more than 50 percent African American.

Once a bastion of white flight, the community was in a process of racial transition. At the same time, disinvestment in St Louis — and with disinvestment, the decline of local public services, including, crucially, local public schools — placed immense pressure on older, relatively affordable suburbs like Ferguson. Increasingly, these communities grappled with aging infrastructure, growing public service needs, and fiscal stress.

The Local Politics of Fiscal Austerity

In new postwar suburbs with large houses on big lots, revenues were generally stable, and demand for public services manageable. But in places like Ferguson, it was a different story. To remain fiscally sound, they needed new construction, the steady appreciation of property values, generous state and federal aid, and regional infrastructure investment. None of that would last.

To be sure, weak local finance in the United States was not a new development. Because the US Constitution grants local governments no explicit authority, they wield only those powers granted by state statutes and by the “home rule” provisions set out in some state constitutions.

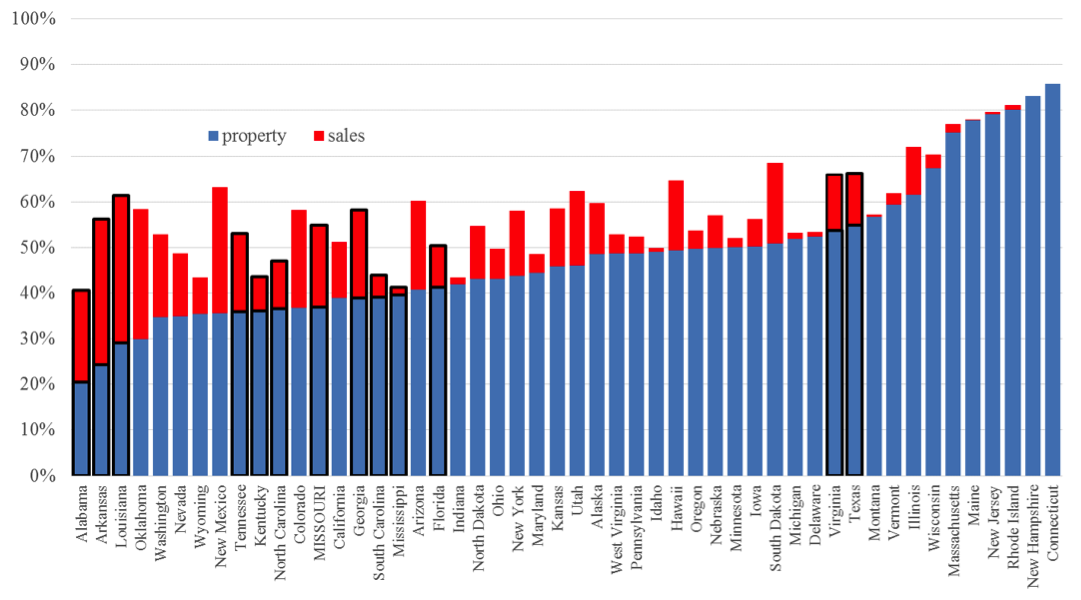

In former slave states like Missouri, slaveholders’ aversion to paying taxes on their human property combined with an aggressive disinterest in public goods provision to further erode local fiscal power. Former slave states tended to tax property lightly and to lean heavily on regressive sales and use taxes (see Figure 1).

(Former slave states outlined). Source: Bureau of Census, State and Local Government Finance

But Ferguson’s fiscal situation grew more precarious in the postwar years. Public officials considered raising taxes to put the city on firmer financial footing. In 1984, in the city’s Combined Annual Financial Report (CAFR), officials wrote, “Because Ferguson is a fully developed community, only an increase in the City’s general taxing effort will provide significant growth in revenues.”

This strategy was vexed, however. The 1980 Hancock Amendment to the Missouri state constitution requires voter approval for all property tax levies and sales tax increases, constraining local governments’ capacity to raise money.

In addition, although estimated actual property values in Ferguson held steady through the 1970s and grew from the mid-1980s until the economic crash in 2007, assessed property values remained low and flat (see Figure 2). Indeed, from 1973 until 2015 local property taxes sustained, on average, barely 10 percent of Ferguson’s general fund revenues (see Figure 3).

To make matters worse, hyper-decentralization made competitors out of regional neighbors. Between 1930 and 1970, a full seventy-eight municipalities incorporated in St Louis County, thrusting Ferguson — one of just six municipalities in the county at the turn of the century — into a fierce inter-jurisdictional competition for funds. Local governments waged annexation battles over pockets of unincorporated land that promised financial return. In one particularly prolonged and bitter showdown, North County municipalities fought over which government would add to its tax rolls the Fortune 500 firm Emerson Electric.

Ferguson won. But the victory was hollow, since the dominant strategy for luring commercial ratepayers was to promise not to collect their taxes. As Walter Johnson has argued, Ferguson relied on a combination of incentives — including rolled-back property tax assessments, real estate tax abatements, and public construction subsidies — to attract new investment. Such gambits rested on the hope that the money foregone in property taxes would be made up in local sales taxes, the single greatest contributor to Ferguson’s general fund.

Today some of Ferguson’s largest ratepayers (big-box stores like Walmart and Home Depot) sit in tax-increment financing (TIF) districts, where increases in property tax revenue (and, in the case of the most recent TIF district, increases in sales tax revenue as well) are siphoned off to pay back the bonds the city used to finance their development. To make matters worse, property owners’ appeals to St Louis County for reassessments are often successful (see Figure 4). In 2011, a single Emerson reassessment cost Ferguson more than $50,000 in foregone revenue for the following year.

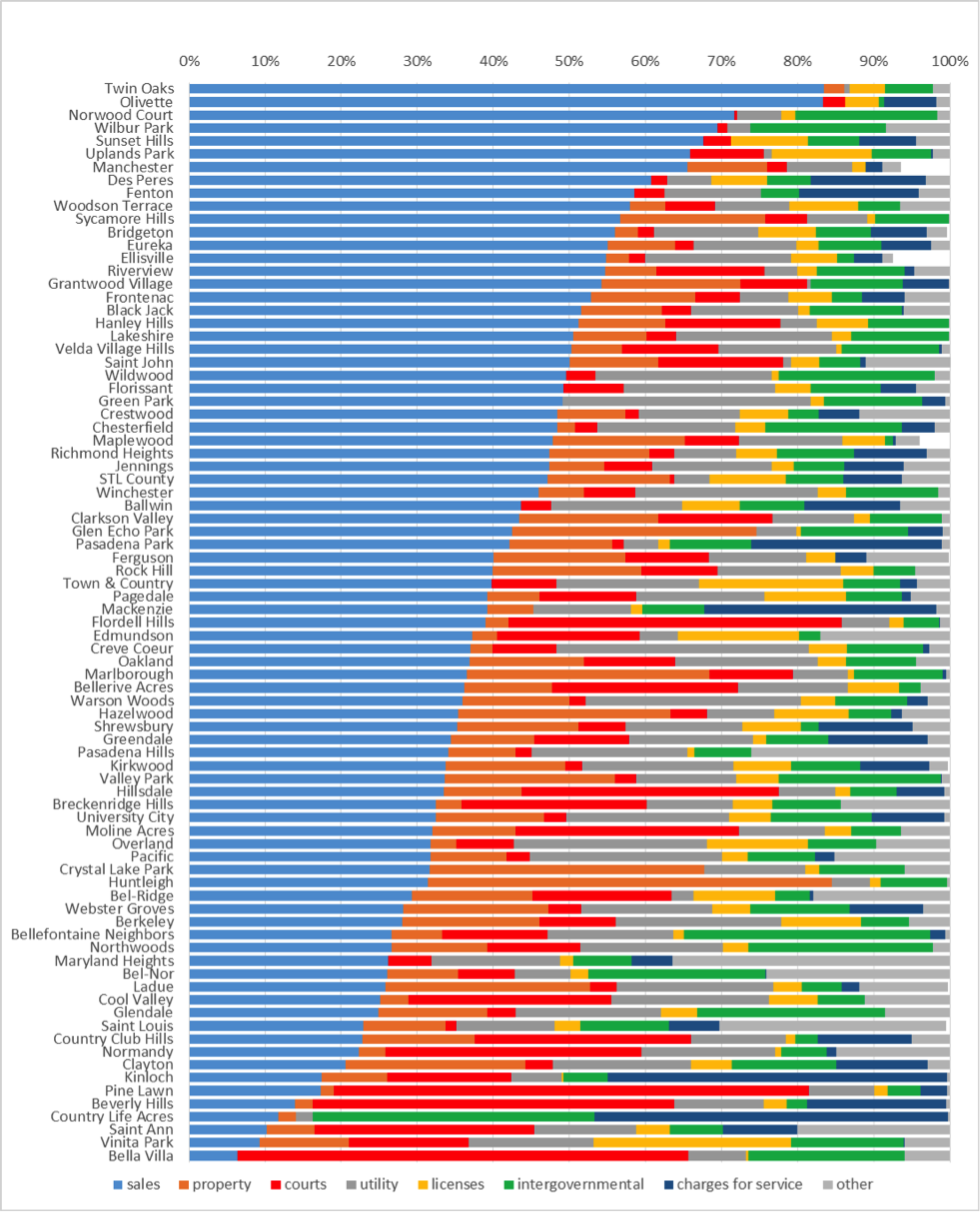

Meanwhile, the rules of the game ensure that Ferguson’s region-wide scramble for revenue is largely futile. The state of Missouri allows municipalities to opt in or out of a countywide sales tax pool. Those that opt in divide the revenue in the pool, while those that opt out keep their locally generated revenue. For municipalities rich in commercial development, this is an easy choice (see Figure 5).

But not so for municipalities like Ferguson, where the retail base is weak and faltering, and the concessions made to attract commercial development guarantee that gains will be few. Ferguson’s CAFRs show that, at least since the early 1970s, officials have closely monitored sales tax revenues, jumping in and out of the state pool year to year in a (largely ineffective) attempt to game the system.

As Ferguson doles out tax abatements and low commercial assessments, other municipalities do the same, playing musical chairs with scarce retail investment and sales tax revenue. In 1994, Ferguson’s finance director glumly noted that a dip in sales tax revenue was “attributable in part to the opening of more outlets in the St. Louis area by one of our major businesses [Walmart] which tends to draw customers to the new locations.”

In the St Louis County jurisdictions where need is the greatest, conventional revenue streams are the least reliable. Consider school funding. In the Ferguson-Florissant school district, the 5.3 percent levy nearly reaches the state-allowed limit but generates only about $6,200 per student. In nearby Clayton, the wealthy, predominantly white county seat, a 3.7 percent levy generates nearly three times that: $17,155 per student.

Transfers from other levels of government only partly fill these gaps. After sales taxes, Ferguson’s largest sources of revenue from the early 1970s through the early 2000s were transfers from the state of Missouri (including the city’s share of state gas, road and bridge, motor vehicle, and cigarette taxes) and the federal government (for example, Housing and Community Development Grants).

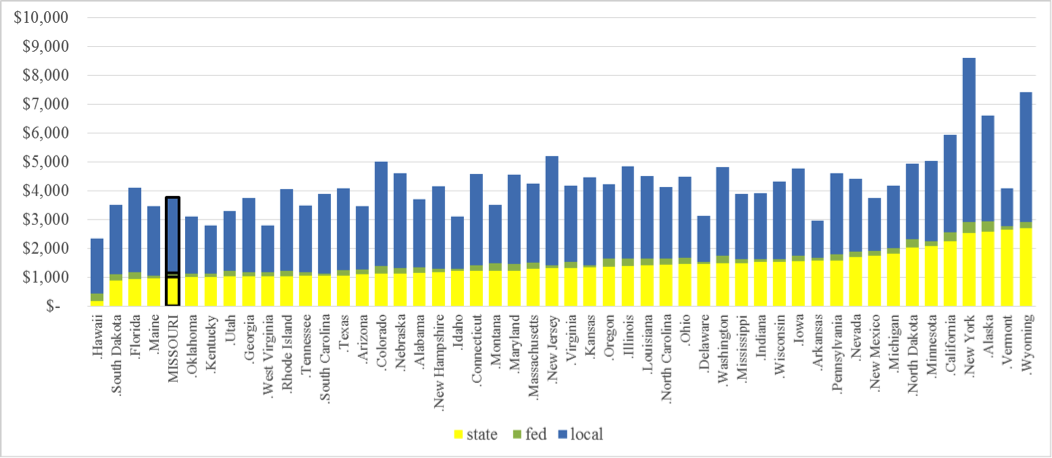

But in the past decade, aid to local governments has dropped sharply. In 2013, for example, local Missouri governments received less than $4,000 per capita in state and federal transfers. Because much of this aid comes with strings attached, intergovernmental transfers contribute little to Ferguson’s general fund (see Figures 6 and 3, respectively).

And because many state and federal transfers are calculated on a per-capita basis, they have declined with Ferguson’s population, even as the city’s costs have trended upward.

Policing for Profit

The city’s “solution” to this financial dilemma is well-known. As the DOJ’s report outlined last year, Ferguson turned to its police department and its municipal court for an alternative source of revenue. Local tax dollars had declined and public service costs had risen during the same period when black St Louisans had moved north into Ferguson and neighboring suburbs. It was then that local policing and local courts came to be characterized by their now-notorious regulatory intensity and racial bias.

Absent stable revenue from conventional sources, local authorities began mining the most vulnerable for money. As the DOJ noted, by the time Darren Wilson confronted Michael Brown, Ferguson’s police department and municipal court had been systematically targeting the city’s black residents for years, extracting exorbitant fines for minor infractions and gratuitously arresting and jailing people who proved unable pay.

“The City,” the DOJ wrote, “budgets for sizeable increases in municipal fines and fees each year, exhorts police and court staff to deliver those revenue increases, and closely monitors whether those increases are achieved.” In 2010, for example, Ferguson’s finance director warned the city’s police chief that “unless ticket writing ramps up significantly before the end of the year, it will be hard to significantly raise collections next year.” He continued: “Given that we are looking at a substantial sales tax shortfall, it’s not an insignificant issue.”

The following year, the DOJ reported, the acting prosecutor of the municipal court “talked with police officers about assuring all necessary summonses are written for each incident, i.e. when DWI charges are issued, are the correct companion charges being issued, such as speeding, failure to maintain a single lane, no insurance, and no seat belt, etc?” The goal, the prosecutor stressed, was to ensure “that the court is maintaining the correct volume for offenses occurring within the city.”

By 2013, the Ferguson Municipal Court was processing almost 25,000 warrants and more than 12,000 court cases annually — a rate of 3 warrants and 1.5 cases for each household in its jurisdiction. What Ferguson’s acting prosecutor called the “correct volume” of charges had little to do with public safety. Instead, its “correctness” depended on its capacity, in the words of Ferguson’s finance director, “to fill the revenue pipeline.”

And fill it they did. In 2001, fines and forfeitures surpassed property taxes as a source of general fund revenue. By 2013, they comprised a full 20 percent of municipal revenues (see Figure 7).

The shift was not lost on local officials, who noted in 2006 that “[p]olicing efforts [had] contributed $313,138 in additional revenue over 2005–06 budget figures,” and listed “[e]nhanced policing efforts” as a key cause of that year’s general fund balance increase. “Fines and forfeitures,” they wrote approvingly, “were $365,221 over budgeted figures due to the increased efforts of the Police Department.”

Who Killed Michael Brown?

Responsibility for Michael Brown’s death — and for the systemic racial and economic injustices it has come to represent — lies with more than just Darren Wilson.

It lies with the local officials in Ferguson who presided over the city’s predatory system of policing and its exploitative municipal courts. It lies with elected officials in well-off St Louis County suburbs, who hoarded scarce resources and valuable opportunities for the benefit of their affluent constituents. And it lies with elected officials at the state and the federal levels — and pro-austerity business interests — who created the fiscal crisis that fueled Ferguson’s hyper-reliance on police and courts.

Ferguson, Missouri is in many ways typical of older American suburbs, where declining property values, diminished support from higher levels of government, and a beggar-thy-neighbor scramble for sales and property tax revenue have produced a yawning chasm between local authority and local capacity.

Governments like Ferguson’s can do much harm. But many — especially those that serve the most vulnerable — can’t do much good.

Brown’s death, along with the protests that followed, helped throw a spotlight on this problem, which remains among the most pressing challenges facing urban and suburban America.