When US Labor Opposed Nuclear Weapons

The labor movement has a key role to play in opposing the madness of a nuclear arms race and the possibility of nuclear war. In the 1980s, progressive unions did just that.

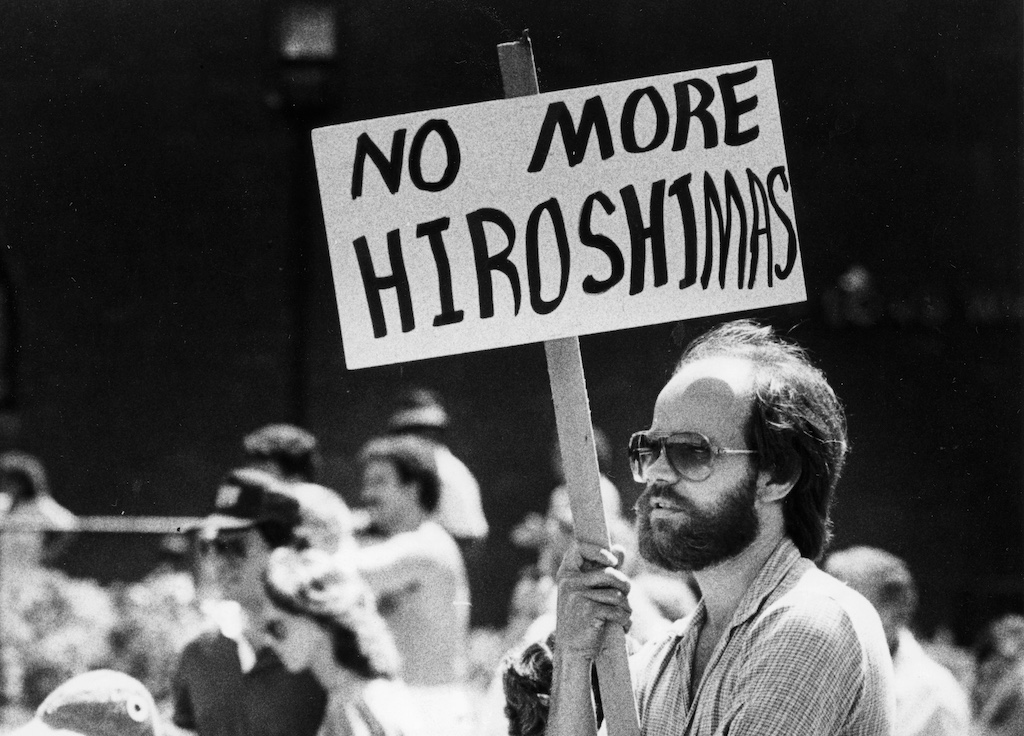

A protest at the waterfront park in Boston, Massachusetts, on August 6, 1983. (John Blanding / the Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Eighty years ago today, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, leveling it and killing an estimated 140,000 people. Three days later, the United States hit Nagasaki with a second atomic bomb, killing another 75,000. Since then, humanity has lived under the constant danger of complete destruction by nuclear weapons.

Though it no longer gets the same amount of public attention it received during the Cold War, the threat of nuclear annihilation remains frighteningly possible today. There are currently over 12,000 nuclear warheads in the world. The vast majority are held by the United States and Russia, the rest by seven other countries. These weapons include hydrogen bombs, which have one thousand times the destructive potential of the bombs used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Responding to the increasingly reckless militarism of major nuclear powers, atomic scientists earlier this year set the “Doomsday Clock” closer to “midnight” than it has ever been, signaling that the world is moving perilously close to catastrophe.

Rather than earnestly engaging in arms-control talks or shifting budget priorities away from the trillion-dollar war machine, the US government under both Democrats and Republicans has been busily carrying out an historic upgrade to its nuclear arsenal by building new submarines, bomber jets, land-based missiles, plutonium pits, uranium-processing facilities, and underground silos across the country (but not without grassroots pushback in the affected communities). This is all projected to cost $1.7 trillion over thirty years, or $77 billion per year — even as Republicans cut funding for health care, education, nutrition, and other vital public services.

Many of the skilled workers who are helping revamp the US nuclear arsenal are unionized. For example, the 2,400 Marine draftsmen designing a new fleet of nuclear submarines at General Dynamics Electric Boat are members of United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 571. This May, they won a new collective bargaining agreement after waging a spirited contract campaign.

This is nothing new. A week after the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) highlighted the labor movement’s key role in the extraordinary efforts to produce the first atomic bombs. “Not only did the CIO leadership aid in labor recruitment,” the CIO News reported, “but much of the equipment was supplied by CIO workers in Allis-Chalmers, Chrysler, General Electric, US Rubber and Westinghouse plants.”

But there is also a long history of trade unionists and labor leaders speaking out against nuclear weapons and advocating for an alternative economy where, instead of depending on the military-industrial complex for employment, workers could have stable jobs producing socially useful civilian products.

“It is a terrible thing for a human being to feel that his security and well-being of his family hinge upon a continuation of the insanity of the arms race,” UAW president Walter Reuther said near the end of his life. “We have to give these people greater economic security in terms of the rewarding purpose of peace.”

US labor’s opposition to nuclear weapons was never clearer or stronger than in the 1980s, when a right-wing president was defunding social programs, firing federal employees, and undermining collective bargaining while simultaneously rewarding his rich friends and taking provocative actions overseas that risked starting World War III. Given some of the disturbing parallels between then and now, it is urgent for today’s generation of union activists to recall and take inspiration from the history of the labor movement’s support for a nuclear weapons freeze.

The Freeze Campaign

In 1981, Ronald Reagan entered the White House as the most conservative president since before the New Deal. During his first year in office, he gave a massive tax cut to the wealthy, slashed the social safety net, and declared war on organized labor by firing over 11,000 striking air traffic controllers.

At the same time, the new Republican president dramatically increased the Pentagon budget in line with his belligerently anti-communist foreign policy. Rather than continue his predecessors’ policy of easing superpower tensions through détente, Reagan aimed to revive Cold War hostilities and accelerate the nuclear arms race.

Several members of the Committee on the Present Danger, a group of high-profile cold warriors determined to undermine arms-control talks between the United States and Soviet Union, were appointed to key posts in the new administration. Reagan’s secretary of defense, Caspar Weinberger, even publicly suggested that the United States could “prevail” in a nuclear war.

In this context, peace activists including MIT researcher Randall Forsberg and Vietnam-era draft resister Randy Kehler launched the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign, which called on the US government to negotiate with Moscow on a mutual and verifiable halt to the testing, production, and deployment of nuclear weapons. The campaign adopted the grassroots strategy of gathering millions of petition signatures and placing freeze referendums on local, county, and state ballots all over the country. In the November 1982 midterm elections, voters approved freeze resolutions in eight states and multiple cities representing about a quarter of the entire US population.

Among those organizing in support of the many local freeze referendums were trade unionists.

“Because it was actually on the ballot, local unions were drawn into that activity,” says Gene Carroll, a longtime union organizer and labor educator. “It was a real, concrete thing. It wasn’t just an idea.”

As the Freeze Campaign built momentum, Carroll was hired onto its staff in the role of national labor coordinator. He traveled around the country connecting unions with local peace activists and mustering labor’s support for the ballot measures, with the ultimate goal of getting national unions on board.

“My job was to take the energy of a particular union that was active at the local level and position people to argue for getting their national union to pass a [freeze] resolution, either by executive board or at their annual convention,” he explains. “I was riding that wave and trying to do what I could to make the wave as big and potent as possible.”

Carroll says union members easily understood that nuclear war posed an existential threat to everyone, and they could also see the juxtaposition between Reagan’s cuts to social welfare programs (right as millions of industrial workers were losing their jobs because of plant closings) and the billions of dollars the president was simultaneously spending on new nuclear bombers, missiles, and submarines.

“The Freeze Campaign was seen as a mobilization against Reagan’s policies, and it didn’t take a rocket scientist to make the link,” Carroll says. “Since labor was under attack at the same time in a big way, that helped fuel their participation.”

Though he was on staff with the Freeze Campaign, Carroll’s salary was paid by two sympathetic national unions: the International Association of Machinists (IAM) and United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW).

The president of the IAM at the time was William Winpisinger, a democratic socialist who championed a planned economic conversion away from war-related industries toward socially useful civilian production — which was particularly remarkable because the IAM is the union with the largest presence in the arms industry.

“What the hell does an individual’s job mean if it’s destroyed in the mad scientists’ global laboratory?” Winpisinger rhetorically asked in 1986. “There’ll be no paychecks in a nuclear winter.”

The UFCW’s financial support for Carroll’s work was largely thanks to the union’s retired vice president Jesse Prosten, a veteran of the Communist Party who had helped build the progressive United Packinghouse Workers union decades earlier.

Cracks in the AFL-CIO

But not all labor leaders were friendly toward the idea of a nuclear weapons freeze. Many top officials at the national labor federation, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), were ardent anti-communists who backed Reagan’s hostile foreign policy even while fighting him on domestic issues. AFL-CIO president Lane Kirkland, for example, was a founding member and cochair of the Committee on the Present Danger, advocating for the United States to expand its nuclear arsenal.

“The fact that he was a member of that group is such a disgrace historically, and it shows you the kind of influence that that worldview had on the federation,” Carroll says.

But thanks to grassroots pressure from the local unions, several of the AFL-CIO’s national affiliates began passing freeze resolutions in early 1982. Besides the IAM and UFCW, other early supporters included the UAW, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU), the National Education Association (NEA), the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), and the United Farm Workers.

“If we do not send a strong, overwhelming message to Presidents Reagan and [Leonid] Brezhnev that the madness of the arms race must be stopped immediately,” AFSCME president Gerald McIntee told delegates at the union’s convention that June, “then all the struggles for economic and social justice for which we have all sacrificed for so long will be meaningless.”

ACTWU president Murray Finley and secretary-treasurer Jack Sheinkman argued that “the enormous resources being devoted to the arms race has come at severe cost to our members, to all working people.”

“The economy is in depressing trouble and record numbers are unemployed,” they continued, “yet military expenditures continue to increase.”

The United Electrical Workers and International Longshore and Warehouse Union — both leftist unions that were independent of the AFL-CIO — also backed the freeze, as did the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists (CBTU) and several state labor federations and central labor councils.

But to Carroll, one of the campaign’s most significant victories was securing the support of the AFL-CIO-affiliated Communications Workers of America (CWA), whose leaders had traditionally been hawkish cold warriors.

“If we created a crack in the AFL-CIO foreign policy worldview, it would be because we had unions like CWA on board,” he explains.

To further gain the support of workers and the labor movement, a group of researchers with the Freeze Campaign published a forty-five-page manual detailing the economic impacts of a nuclear freeze.

The document, which was endorsed by several unions, argued that the bloated military budget was only exacerbating unemployment and inflation, and that a nuclear weapons freeze would free up more than $200 billion in the federal budget over the next decade to spend on infrastructure, mass transit, alternative energy, worker retraining, and social welfare.

“Stop the War Spending, Stop the War on Unions”

On June 12, 1982, the Freeze Campaign and other antiwar groups organized a massive demonstration against nuclear weapons in New York City’s Central Park. An estimated one million people participated, making it the largest single-location protest in US history.

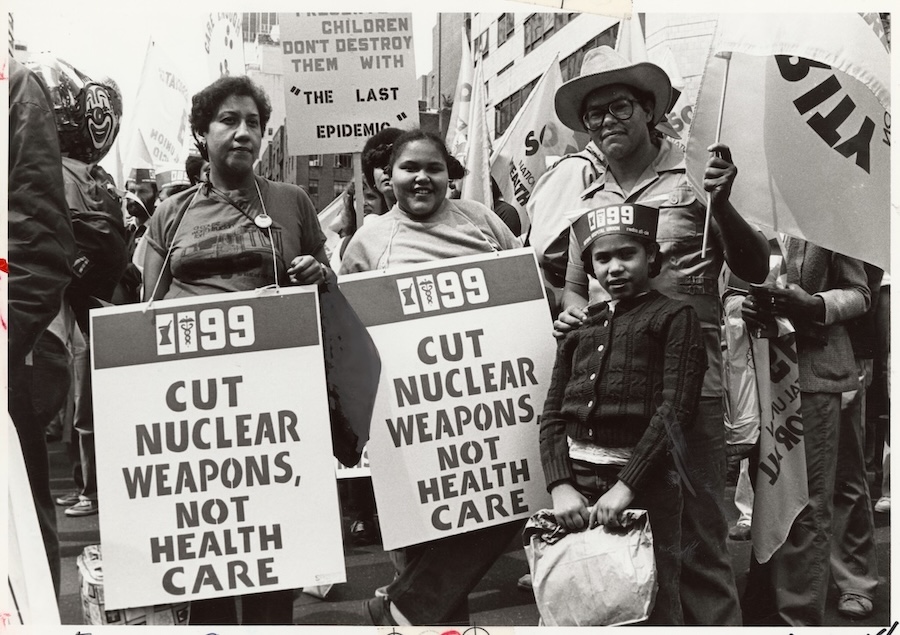

To coordinate labor’s support for the event, a New York City Trade Union Committee for a Freeze was established. The rally was endorsed by the IAM, CWA, NEA, AFSCME, CBTU, District 65, and 1199-National Union of Hospital and Health Care Employees (which would later merge with SEIU in 1998).

On the day of the march, members of 1199 carried signs reading “Cut Nuclear Weapons, Not Health Care,” while a United Steelworkers Local 1010 sign demanded “Stop the War Spending, Stop the War on Unions.” Labor Notes editor Kim Moody, who joined the march, reported seeing countless signs and buttons declaring “jobs not war” and “feed the poor, not the war makers.”

Though Moody expressed disappointment at the time that the labor contingent was “dwarfed by church, professional, artistic, and regional delegations,” Carroll says that union support nevertheless played an important role in the rally’s success. Speakers at the event included ACTWU’s Sheinkman and IAM vice president Sal Iaccio.

By 1986, a total of twenty-three national unions had officially endorsed a nuclear weapons freeze. In addition to the initial supporters, the Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Teachers, Newspaper Guild, National Association of Letter Carriers, United Steelworkers, and International Chemical Workers’ Union had also gotten on board, among other unions.

Partly in response to the Freeze Campaign, Reagan softened his nuclear policies in his second term. He and new Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev jointly proclaimed in 1985 that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” The two leaders successfully negotiated the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty to ban the use of ground-based nuclear missiles, a treaty President Donald Trump tore up in 2019.

The US public’s fear of nuclear Armageddon has dissipated in the years since the Cold War officially ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, while other global threats like climate change and pandemics have understandably received more attention. But with the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, escalating US-Israeli aggression across the Middle East, and heightened tensions between India and Pakistan, among numerous other conflicts, the possibility of nuclear war is as high as it has been since the 1980s.

Comprising millions of workers across numerous sectors, including the arms industry, the labor movement continues to have a crucial role to play in advocating for a more rational economy geared toward worker justice and world peace. Recently, scores of unions and labor organizations at the state, local, and national level have joined Veterans and Labor for Sensible Priorities, a campaign calling for $100 billion to be removed from the Pentagon budget to instead fund social programs and tackle the climate crisis.

“It’s about your vision of the role of the labor union in society,” Carroll says. “We talk about being for democracy and fairness and dignity — it’s not a stretch to say we should be opposed to nuclear weapons too.”