Trump’s Tariffs Defeat Spells Long-Term Danger for the Left

Progressives celebrating the Supreme Court’s anticipated ruling against Donald Trump’s tariffs risk encouraging the consolidation of a dangerous legal doctrine that will be used to defeat their own agenda for decades to come.

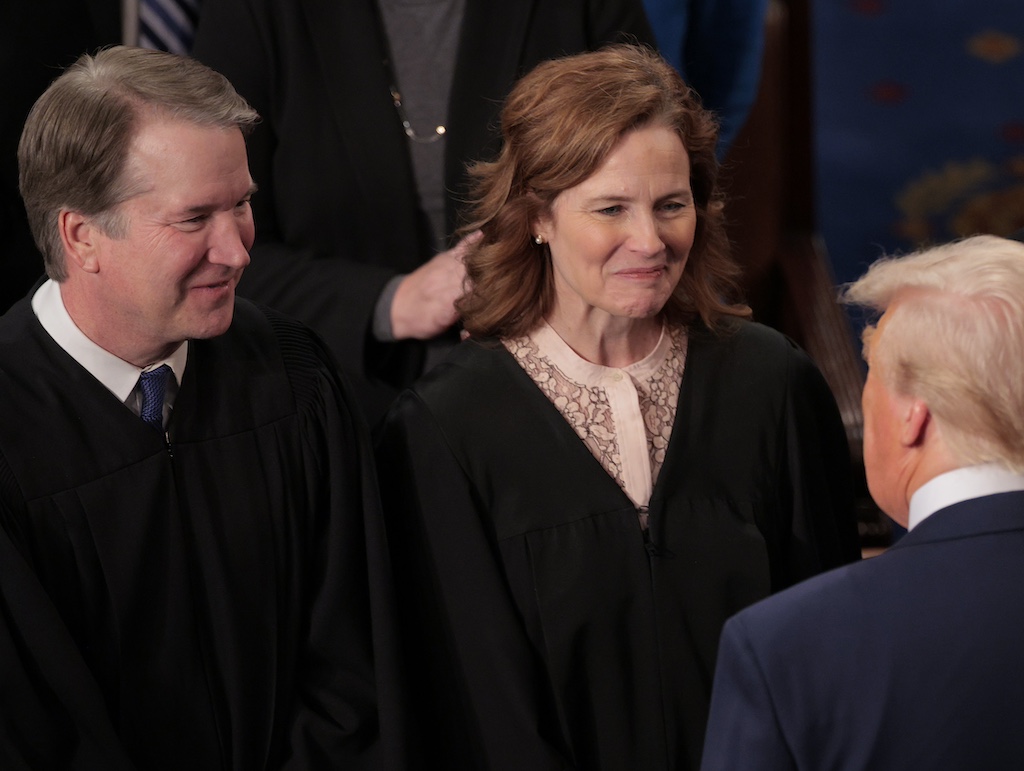

That the major questions doctrine may now be used to rein in the Trump administration’s trade policy should give no one comfort, particularly not progressives or liberals. (Chip Somodevilla / Getty Images)

Perhaps as early as this Friday, the Supreme Court will announce a ruling in the Trump administration’s tariff cases, Learning Resources v. Trump and Trump v. V.O.S. Selections. The takeaway from the oral argument back in November was clear: the administration is in trouble and headed for defeat.

For many on the Left, such a blow to Donald Trump’s authoritarian administration might sound like cause for celebration. It is not.

Apart from the fact that such a ruling would pose little threat to Trump’s punitive tariffs, which the White House could pursue under different statutes, the main problem is that any decision invalidating the current tariff regime would almost certainly rest on the Supreme Court’s increasingly aggressive use of the major questions doctrine.

The court is likely to argue that if Congress wanted to authorize tariffs with the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) — as the administration claims — then it would have said so clearly. By using the IEEPA as a legal basis for imposing tariffs, the Trump administration is taking an action with “vast economic significance” (that is, acting on a “major question”) and stretching the 1977 act beyond recognition. In other words, the executive has overstepped its authority.

Although at first glance a decision based on this logic does not appear dangerous, the recent history of the major questions doctrine demonstrates its potential to empower an unelected and highly conservative judiciary to obstruct social progress. A ruling against the Trump White House would further entrench this menacing legal principle.

The doctrine has already done enormous damage. The first case to explicitly invoke it was West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency in 2022, in which the court blocked federal climate regulation by demanding “clear congressional authorization” for the Environmental Protection Agency to regulate carbon dioxide emissions. In 2023, in Biden v. Nebraska, the court struck down student loan forgiveness on similar grounds, insisting that, despite the extremely broad language of the 2003 HEROES Act, Congress did not authorize widespread student debt relief, as it did not state so precisely and explicitly.

As the liberal Supreme Court justices pointed out in these cases, the major questions doctrine essentially imposes a “clarity tax” on the legislative process. Congress must legislate with a level of specificity that is usually impossible to achieve, and federal agencies are stripped of the autonomy and discretion required to rein in corporate power. The result is not a restoration of democratic accountability; to the contrary, this novel legal doctrine consolidates power in the courts, the branch of government least accountable to the public.

That the major questions doctrine may now be used to rein in the Trump administration’s trade policy should give no one comfort, particularly not progressives or liberals. The principal purpose of the major questions doctrine will continue to be blocking climate action, industrial policy, labor protections, and any serious attempt from the Left to challenge entrenched economic elites. Progressives celebrating this ruling risk encouraging the construction of the very legal architecture that will be used to defeat their own agenda for decades to come.

To be sure, progressives and liberals who have inveighed against the legality of Trump’s tariffs likely understand the potentially perverse consequences of a ruling that rests on the major questions doctrine. During oral argument, legal scholar Neal Katyal, an important figure in the liberal legal movement, carefully avoided referencing it. Katyal’s core claim is that a tariff is a tax, and taxation is and always has been an inherently legislative power (similar arguments were made by leading progressive law professors Akhil and Vik Amar). Therefore, if Congress is to delegate such a core legislative power to the executive branch, it must do so explicitly — and it did not do so in IEEPA, which speaks only generally of “penalties” and “sanctions” against foreign nations rather than tariffs.

This is a smart argument. It appeals to originalist ideas of history and tradition without reviving the reactionary, anti–New Deal jurisprudence of the 1930s, which challenged the very constitutionality of the administrative state. Katyal’s argument also emphasizes that the problem here is not the delegation of legislative authority per se but rather the delegation of taxation-related powers. The court’s three liberal justices are likely to underline this distinction further in concurring opinions if the court ends up ruling against the Trump administration. They will argue, as will liberal legal commentators, that Trump lost because he abused his power to such a great extent that he provoked his own judicial appointees to rebel against him.

The problem, however, is that no matter how hard the liberal justices try to finesse this issue, there is no way they can avoid cosigning an opinion that invokes the major questions doctrine. The doctrine is simply the only route to five, six, or even seven votes against the administration in this case. This means that a defeat for the White House would depend on liberal justices’ formal acceptance of the major questions doctrine for the very first time.

Thus, regardless of what the liberal justices say in any concurring opinion, they will be strengthening a doctrine that they have, more or less correctly, labeled a conservative cudgel against progressive policies. If the major questions doctrine is wielded against Trump, conservative judges and activists will be able to claim that the doctrine is not, after all, a conservative weapon. Moreover, an opinion of this sort would not only legitimize the doctrine but would also — at least to some extent — legitimize the court by helping to counter the view that it is subservient to Trump.

Lurking in the background, key conservative groups see the tariffs case as an opportunity to institute long-standing legal protections for neoliberal economic policies. The US Chamber of Commerce, the Cato Institute, the Goldwater Institute, and the National Taxpayers Union Foundation are among the libertarian and free-market advocacy groups that took the trouble of writing friend-of-the-court briefs against the Trump administration.

The tariffs case is a perfect Trojan horse to advance their interests. It can be sold to critics to Trump’s left as a blow to his authoritarian ambitions, when the real goal is not to hurt Trump but instead rein in his minor deviations from right-wing economic orthodoxy — and to ensure that future presidents are similarly constrained.

It is certainly true that if Trump loses this case, he will be able to implement tariffs under other legislative authorities, such as the 1962 Trade Expansion Act. Justice Amy Coney Barrett even hinted during oral argument that some tariffs could be preserved if they are repackaged as licensing fees. For practical reasons, the court is also unlikely to demand full refunds on tariffs that have already been paid. These loopholes, for both conservative judges and activists, are not especially concerning. The continuation of tariffs in some other form or the failure to receive full compensation for tariffs that should not have been paid will be a price worth paying for the consolidation of a legal doctrine that will overwhelmingly be used against the Left for the foreseeable future.

While the major questions doctrine is sold by its proponents as a necessary constraint on an imperial presidency, the reality is that it is part of a larger set of legal tools that many conservative and libertarian activists see as a means of converting their current domination of the federal judiciary into a permanent entrenchment of monopoly capitalism.

Leaving aside the fact that the framers of the US Constitution had no real conception of capitalism, gave the federal government formidable tools to regulate the economy, and detested the prospect of concentrated economic power, the Left should obviously be troubled by legal doctrines that empower an unelected judiciary to insulate oligarchs from even the most minimal and half-hearted challenges to their wealth and influence. Far from being celebrated, a defeat for the Trump administration in the tariffs case should revive the classic leftist position on the judiciary: that it is a foe, not a friend.