Latin America Is the Prime Target for Trump’s Warmongering

While Donald Trump fires off threats of military action against countries from Greenland to Iran, Latin America is the main focus for his strategy of imperial retrenchment. The Latin American left will have to build new alliances against US aggression.

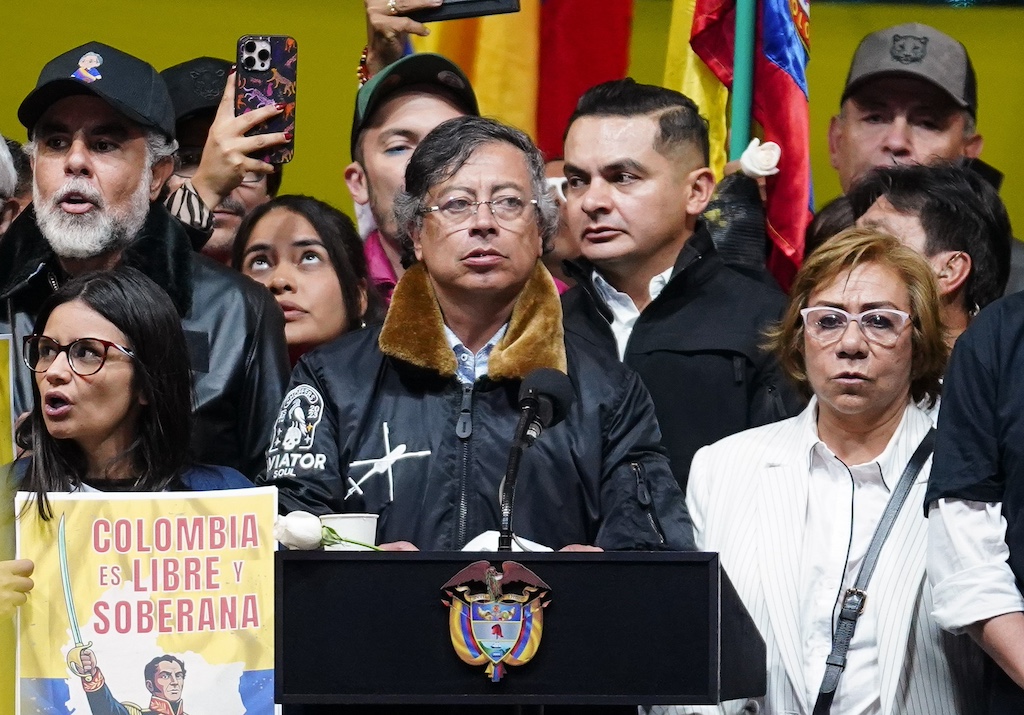

Colombian president Gustavo Petro speaks during a rally in defense of national sovereignty in Bogota on January 7, 2026. (Andres Moreno / Xinhua via Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Daniel Finn

The US attack on Venezuela and the kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro forms part of a declared plan from the Trump administration for imperial retrenchment in the western hemisphere. Donald Trump and his allies have already made threats of further military aggression against countries like Cuba and Colombia. How seriously should we take those threats, and what are the prospects for resistance to Washington’s new strategy in Latin America?

We spoke to Tony Wood about the situation now facing the Latin American left. Tony is assistant professor of Latin American history at the University of Colorado Boulder and a regular contributor to publications like the New Left Review, the London Review of Books, and Jacobin. He’s also the author of two books about Chechnya and Russia under Vladimir Putin.

This is an edited transcript from Jacobin’s Long Reads podcast. You can listen to the interview here.

Leading up to the US attack on Venezuela, you had a number of developments that seemed to be favorable for the kind of politics that Donald Trump and others would want to promote in the region: the eviction of the Left from power in Bolivia after more than two decades; the victory of a far-right Pinochet defender in Chile’s presidential election; and electoral victories for the Right in Argentina and Honduras after direct, heavy-handed intervention by Trump himself, telling people who to vote for.

Would you say that those successes created a sense of momentum or confidence that emboldened the Trump team to act in the way that they did?

Some of these developments were driven by their own internal dynamics, as in the Bolivian case. The collapse of the long hegemony of the mass movement led initially by Evo Morales and later by Luis Arce had a lot of internal drivers, whereas the heavy-handed rhetorical intervention in Argentina and Honduras by the Trump administration was more direct.

I think we have to make a distinction between long-term shifts that are happening in Latin America — partly because there’s a push against the incumbent government, whatever it may be, and it happens to be the Left in Bolivia — and developments that are part of a rising tide of right-wing success.

The case of Argentina is a good one to consider. The election of Javier Milei stemmed from the long-term decline of the center-left version of Peronism and the rise of a libertarian, hard-neoliberal right. That happened in 2023, but then Trump is in power and he has a like-minded regime that he wants to bolster, so he exerts pressure and it turns out to be successful. There’s an element of opportunism here rather than a causal connection.

To some extent, the Trump administration didn’t really need the encouragement to act. They probably would have done something similar to Venezuela even if they hadn’t had these recent successes, because they’ve had Venezuela in their sights for a long time. That also applies to the Biden administration in between Trump’s two presidencies.

All of them have maintained the sanctions on Venezuela, with pressure strategies designed to coerce Maduro’s government and bring it to its knees. Trump, of course, attempted a regime change operation during his first administration in 2019 that didn’t succeed. There’s a sense in which he was going back to have a second go at something that looks like regime change but doesn’t involve all of the messy responsibility for nation-building.

Overall, I would say they may have been partly emboldened by the shift in the regional context, but Venezuela is also something that’s been on their agenda for a long time and they may have done it regardless of the wider context.

In spite of those advances for the Right in a number of countries, there are still a number of left governments throughout Latin America, from Brazil to Mexico, Colombia, and Chile, where despite the recent victory of the Right, Gabriel Boric is still the outgoing incumbent. What were the relationships of those left governments with Maduro and the PSUV [United Socialist Party of Venezuela] in Venezuela on the eve of the US attack? How did they respond to the attack when it happened?

The original “Pink Tide,” going from the 2000s into the 2010s, and the more recent wave of left-wing governments from 2018 onward, sometimes referred to as Pink Tide 2.0, were both quite heterogeneous in their outward orientations and their diplomatic relations. There hasn’t really been a united front when it comes to Venezuela in particular.

Boric was much more critical of the Maduro administration, and he has also been critical of Cuba. He is much more insistent on the need for democratic credentials in the sense of formal electoral processes, and he has been quite clear in differentiating his version of the Left from the Chavista/ Bolivarian version.

[Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva] has been less categorical, but he has not exactly been supportive of Maduro, either. The Mexican government is quite similar. While they didn’t have particularly cordial relations with Maduro, the relationship didn’t tip over into hostility, as with a lot of the right-wing governments in the region.

Part of the issue is that Maduro became somewhat toxic to be associated with, and you didn’t really get anything positive out of it if you were a progressive government in Latin America. If your country didn’t have particular economic ties to Venezuela either, there was no particular benefit in holding the line on Venezuela for any of these governments.

Obviously there’s the issue of solidarity with Cuba, but a lot of those countries maintain that relationship diplomatically without necessarily giving any practical assistance. The big exception there is Mexico, which is actually supplying more oil to Cuba these days than Venezuela is.

Up to Maduro’s ouster, most of these governments were not particularly close to or cordial with Maduro, although they were certainly opposed to US intervention and US pressure on Venezuela as a violation of sovereignty. They would hold that diplomatic line, but they wouldn’t really go beyond that.

I think this is something that did embolden the Trump administration. They believed that no one was going to come running to Venezuela’s defense — certainly not militarily but even diplomatically, the response was always likely to be lukewarm because none of these other governments particularly warmed to Maduro himself. If they had tried something similar against [Hugo] Chávez — and in the past, obviously they did — the response would have been much more united and much firmer.

In the wake of the assault, Mexico and Brazil condemned it, as did Boric. In Colombia, [Gustavo] Petro certainly condemned it in no uncertain terms. There have been a lot of rhetorical attacks on this exercise of US power as an illegitimate violation of Venezuelan sovereignty.

That stance is pretty consistent, but I would also say that it’s a stance on principle after the fact, rather than one born out of any close practical connections to the current Venezuelan government. I would distinguish between the rhetorical level, on which all of these governments agree that US violations of Latin American sovereignty are a bad thing, and their particular connections to the Venezuelan government, which I don’t think they feel a strong impulse to support.

One extra piece I would add to the picture is the effect of Venezuelan out-migration over the past decade or so. Very large numbers of Venezuelan migrants have moved into countries across Latin America, especially places like Colombia and to a lesser degree Chile and Brazil. A lot of these Latin American governments, even the ones on the Left, would be quite happy to see a Venezuelan government that has better relations with the US and sends out fewer migrants, just to address their own issues on that question.

Suffice it to say, Maduro didn’t make himself very popular with other governments, even those of the Left. That accounts for the relatively formal, diplomatic character of opposition to his ouster among those governments. Obviously, the right-wing administrations in the region have been ecstatic and they’re pushing for regime change. José Antonio Kast has said, “We now have to go and finish the job and change the whole government,” which even the US is not going to do.

That brings up the question of how far-reaching the changes in Venezuela itself are going to be. If it’s simply a question of removing one person at the head of the state, that doesn’t necessarily mean that Venezuela is going to sever ties with Cuba. But Trump has been making various statements saying that under Delcy Rodríguez, the Venezuelans are going to be much more compliant than they were under Maduro.

What would you say are the implications of this new situation for Cuba? How serious is the crisis that is facing the Cuban system at present?

Cuba is a very different proposition for the US in a number of ways. Certainly Cuba is in a very bad situation on a humanitarian level: you have the long-term impact of sanctions, combined with the ramping up of those sanctions during the first Trump administration, which the Biden administration did nothing to lift, and the sense of screws being tightened.

In addition, you have the long-term degradation of the country’s economic infrastructure: things like the electricity supply are in terrible shape. There’s also been a very large exodus from Cuba, much larger than previous waves of out-migration such as the boat lifts of the 1980s. What has happened over the past few years is on a different scale altogether. That loss of human resources, with people leaving the island for a variety of reasons, has taken its toll. I would say Cuba is in a very bad situation.

One might think that the Marco Rubio strategy would be to cut off all remaining lifelines and force the regime to its knees. I initially assumed that was the goal, certainly of Rubio and of US policy in general. But from what I’ve seen recently, the US is actually going to let oil shipments from Mexico continue — something like 40 percent of Cuba’s oil is coming from Mexico these days.

This is on the basis that the goal is not to bring about the total collapse of Cuba’s government, but rather to increase pressure and make it more pliable. I don’t know if that will work in Cuba to the same degree. The government is much more of a consolidated entity and much less centered around one personality than in the case of Venezuela and Maduro. The army is much more solid and unified.

I certainly don’t think they’re going to go in and do an occupation or regime change in the near future. I question whether they are even going to try an operation of the Venezuelan type, where you decapitate the regime and make what’s left do your bidding.

To some extent, it is a very bad and threatening moment for Cuba. But while it seems weird to say this in the wake of the US violation of Venezuelan sovereignty, this was actually, so far as the US was concerned, the option requiring the least effort to secure a good outcome in their view. It took a few hours, and they’ve now got a pliable regime in Venezuela without having had to put boots on the ground.

Their view of Cuba will be, “Can we do the same thing?” And if it doesn’t work, what are their other options? How are they going to escalate? I’m not sure they’re willing to escalate as far with Cuba as they did with Venezuela. It’s possible that this is a Trumpian negotiation strategy of whipping out the massive threat and hoping that they fold and agree to hold elections that Rubio’s handpicked person will win.

Here’s another point worth noting. In Venezuela, you had an opposition that has been funded for over two decades by the US. They cultivated leadership figures, one of whom got the Nobel Prize, much to Trump’s irritation. You had a ready-made opposition that you could put in power if you wanted to do a regime change operation on the old US model. But even in that scenario, the US didn’t do it.

In Cuba, they don’t have that infrastructure ready. Despite what the Cuban right-wing lobby in the US has been saying for six decades, it doesn’t have a ready-made alternative to what is currently there in Cuba. As brutish and irrational as the Trump administration is, I think it will have an assessment of the situation and it won’t want to create an Iraq-style quagmire for the sake of placating Rubio.

Obviously Rubio will be pushing for some version of regime change, but I also think he will be happy to wait and just increase the pressure on Cuba along current lines until an opportunity presents itself. That may not be for some time.

In the interim, there will be more suffering for the Cuban people of an intolerable kind. The decades of totally immoral sanctions are going to continue. But I don’t think the US will repeat the Venezuela move on Cuba in the near future, although I could sadly be proven wrong at any moment.

The other country in the region that has explicitly been threatened with force by Trump is Colombia. How dangerous would you say that the current moment is for Colombia and for the government of Gustavo Petro in particular? Does the Colombian left have advantages in any potential confrontation with Trump that Maduro and the PSUV lacked?

On the one hand, Petro hasn’t reached the same heights as Hugo Chávez during his first decade in office in terms of electoral success and concrete gains that he could point to. On the other hand, it’s only been a relatively short period of time since Petro was first elected, and his government doesn’t have the sense of having been in power for a very long time and presiding over a severe economic crisis. Would that put them in a stronger position if the confrontation with Trump develops further?

It’s interesting to think about why Trump made these very overt military threats against Colombia, whether that was a continuation of the Venezuela strategy, or more of a rhetorical device to indicate the existence of the threat. Something to bear in mind is the fact that Colombia has parliamentary elections coming up in March and a presidential election in May, in which Petro’s ally Iván Cepeda is running.

One view would be that the election gives the US the opportunity to secure a more pliable regime in Colombia without the use of military force. There is a right-wing candidate of a [Javier] Milei type, Abelardo de la Espriella, who is poised to do reasonably well in the first round and who could potentially win a second-round run-off against Cepeda. De la Espriella was the legal advisor to the right-wing paramilitaries, and he represents a combination of Milei and Colombian far-right paramilitary politics.

He would be the Trump administration’s ideal president of Colombia, and there’s a good chance that he might win without direct US interference. There are a number of things the US could do (and is likely to try) over the coming months as a destabilization strategy. I can well imagine the US fomenting types of violence to create a climate of insecurity that would favor the Right.

To that extent, I would not see US military intervention in Colombia as being likely in the short term, because you have the election coming up. I do see US meddling coming in both rhetorical form and in the form of covert ops. That is very possible over the coming months in order to get their desired figure elected president.

Colombia is an important piece of the jigsaw for the US. In terms of strategy, they’ve had a military relationship for decades, and having a reliable right-wing relay in Colombia has long been a linchpin for the US politically as well. The ability to secure that outcome by electoral means would be a real asset for the Trump administration that I don’t think is worth endangering by intervening militarily.

In addition to that, direct US military interventions in Latin America could very easily backfire and rally support around people who defend the country’s sovereignty. I could imagine a scenario where the more the US threatens Colombia in the next few months, the better the Left does as a result, because they will be standing up, rhetorically at least, for Colombian sovereignty while the right wing begging for US intervention will be seen as selling out the country.

In terms of whether the Left in Colombia has assets that Venezuela and the PSUV didn’t have, yes, it’s true that Petro has not been in power all that long, relatively speaking. He hasn’t had as much time to consolidate a support base — he hasn’t really had much time for anything positive that his government has done to take root.

Petro has put a lot of emphasis on his total peace strategy, and that has not really succeeded. There have been recent upticks in violence by guerrilla groups and paramilitaries too. This is not to say that the Petro government has failed. There are a lot of things it has done that have succeeded, but it may not be enough to consolidate a support base behind the Left and fend off the right-wing electoral challenge.

On the flip side, in comparison to Maduro, the Left hasn’t been in office as long and there hasn’t been that much time for deep disenchantment to set in. Petro’s government has achievements it can take credit for in terms of land redistribution and decreases in poverty. The question is whether that’s enough to defend an incumbent government in the current climate against a right-wing challenger. We’ll find out over the next few months.

Obviously it’s reckless to generalize about the state of popular opinion in Latin America, because it’s a huge and very diverse region with no necessary sense of common identity (as evidenced by the fact that there has been so much hostility toward Venezuelan immigrants in countries like Chile, even or especially from the Right). But clearly there are also commonalities, notably the fact that they all have to look up at the United States and consider what impact it might have on their societies.

What has been the reaction at the level of popular opinion to the various maneuvers of the Trump administration? Have there been notable interventions from the social movements that are active in the region?

Some of the differentiation concerns how dependent any given country is on the US economically. When you’re looking at Central America, those are smaller countries that are much more dependent on remittances and trade with the US, so they’re vulnerable to all kinds of political pressure for a variety of reasons. Brazil is a country on a totally different scale with a diverse array of trading partners. The tariff threats of the Trump administration backfired because Brazil has at least some theoretical options for diversifying its trade relations and standing up for itself commercially.

At the governmental level, one consequence of the Trump administration’s actions has been to push Latin American elites to get behind regional trade pacts. The EU–Mercosur trade pact has just been signed. It has taken twenty years to get it over the line — Trump’s actions are what finally pushed people to think this was a good idea. You’ve got a fairly large free-trade bloc in South America lowering tariffs with the EU, which gives European capital a significant foothold that it has long been searching for.

To some extent, at governmental level, it’s a question of what other options a country has. In the case of Argentina, the stick being waved over the heads of the electorate was the cancellation of a bailout for a government that has been in financial crisis, both under Milei and under the preceding administration: “We’re going to withhold the life vest from you as you’re sinking.” That’s a very different kind of threat compared with the tariff threat against Brazil.

In terms of popular movements, there have certainly been expressions of rejection of US intervention, with a lot of street demonstrations in Mexico, Brazil, and other places. At the same time, this imperial offensive by the US has been quite selective in its targets so far. The overall strategy is very clear, but in terms of who has actually been targeted to date, it’s quite selective, moment by moment, and that makes it much harder to organize around.

Beyond a general stance of rejecting US imperialism, which has been a constant position of the Latin American left for a century and for very good reasons, there isn’t a concrete issue to organize around as there was with, for example, the imposition of a dictatorship in Chile in the 1970s. We’re in the early stages of discovering what a new wave of solidarity movements would look like and what they would be able to do.

To be sure, there’s a rejection of US interventions, but what is the organizing goal for that within a country like Mexico or Bolivia beyond the expression of public opinion? We’ll have to see how this neo–Monroe Doctrine evolves and who the next targets are to discover how the response of popular movements develops. I would expect an upsurge of anti-imperial sentiment, but what organizational forms that would assume is not clear yet. It may translate into electoral outcomes — that’s the obvious example.

The other question is whether popular movements in Latin America have the capacity to carry out mass civil resistance as opposed to mobilizing around a short-term electoral goal and then demobilizing. That’s something we have seen happen a lot in recent decades. Popular movements will mobilize very successfully to block neoliberal reforms or to elect a progressive coalition, and then there will be a wave of demobilization.

Another point to mention is that there has been a real increase in insecurity in many countries, which has had a demobilizing and demoralizing impact. There is a lot of discourse around security in Latin America with talk of pervasive violence. To some extent, that is a strong right-wing trope, but it’s not entirely fictional all the same. That climate of insecurity is part of what has made the Right electorally successful, but it also affects people’s day-to-day lives, and it drives migration.

All of that makes collective acts of organization and resistance much more difficult. The threat of violence is very discouraging, for good and obvious reasons. Within this generalized climate of insecurity, and with a very broad target such as US imperialism, how do left movements successfully organize around that? I’d like to be optimistic, but in some ways it is a function of what the US does next.

What are the implications of the Trump administration’s new emphasis on hemispheric hegemony for left projects in Latin America? What are the prospects for resistance or even (to put it in more modest terms) for carving out some functional breathing space?

The Trump administration presents its strategy for the western hemisphere — its reassertion of the Monroe Doctrine — as a novelty, but it really conforms to a very old pattern. It’s a reversion to a model for US relations with the western hemisphere that is more than a century old. It was later superseded by the Cold War framework and the US rise to global preeminence.

Curiously, this return to the western hemisphere represents a shrinkage of US ambitions from a certain perspective. Greg Grandin has developed his analysis of this point in several books, particularly Empire’s Workshop, where he argues that Latin America is where the US goes to reinvent itself. It retrenches in the western hemisphere during moments of crisis.

You could think of it in those terms: Trump is a phenomenon of crisis, related to the collapse of the neoliberal dispensation, the long decline of profitability in the US corporate sector, and the vast financial bubbles they’ve had to inflate to compensate for declining growth rates. There is a generalized crisis of US capitalism. At the same time, US global power is faced with the rise of China and the diminishing returns from military adventures such as those in Iraq and Afghanistan.

There’s a logic to US retrenchment in the western hemisphere: to reinvent itself, to reassert its power, to rack up some easy military victories, and then to control the entire hemisphere and dominate its resources, as the National Security Strategy document specifies. The Caribbean in particular is going to be especially vulnerable to abrupt reassertions of US military power without the ambition to engage in nation-building occupations such as it attempted in Iraq.

One could then differentiate between the Caribbean as a primary theater of US aggression and South America as a secondary area. South American countries are much bigger and much more significant both economically and militarily. It would be a different proposition for the US to exert its power over them.

Currently what you have is a huge deployment of US naval forces in the Caribbean, using Puerto Rico as a massive aircraft carrier. I can imagine the US maintaining that posture in the Caribbean for some time to come, but that also means they wouldn’t be doing it in South America. It is a very old pattern but one that is being updated for the age of aircraft carriers, drone warfare, and high-tech military interventions like the one that abducted Maduro.

At the same time, the Trump administration is repeating this pattern from the era of Teddy Roosevelt in a very different historical context. Thinking about interventions in the 1900s and 1910s, the US was the preeminent power in the western hemisphere during that period as well as being an ascendant global power. At that point, you didn’t have the rise of China or large-scale Chinese investments in infrastructure throughout Latin America. You certainly didn’t have China as the main export market for a number of products from Latin American countries.

The US is retrenching to the western hemisphere on the assumption that it can dominate the region in the same way that it did more than a century ago, but in a context where that hold is much more contested, economically at least, between the US and China. In the medium term, we’ll certainly see more military interventions of the Venezuelan type — sadly, that is likely — but also much more of a commercial battle against China, seeking to push out Chinese influence by using US military force to crowbar their way into countries.

It’ll be a zero-sum economic battle with China for influence in Latin America, aiming to make Latin America the sole domain of the US not only in military terms but also in terms of economic resources and profitability. That is clearly what is behind the Trump strategy. I expect that strategy to be violent, and I also expect it to be contested.

The US retrenchment to the western hemisphere makes it very clear what is happening and who the enemy is. The alliance of US corporations with the US military in prying open these countries is going to be very plain, and that in turn will provide an organizing focus for the Left and for progressive movements.

During the 1920s and ’30s, there was a wave of anti-imperialist solidarity and organizing that appealed to a broad swathe of opinion beyond the Left as well. The more aggressive the US becomes, the more that will push Latin American public opinion to consolidate around an anti-imperial alternative. The difficulty that alternative will face is the massive asymmetry of military power in an age of surveillance states and high-tech weaponry. The US has strong allies in the Latin American elites who have access to that technology as well, so the challenges are very steep.

One of the consequences of the Trump administration is to make it very clear what it is that you’re up against. That’s true both domestically in the US itself as well as internationally. You’re dealing with a brutal, authoritarian state apparatus in alliance with (and furthering the interests of) sections of US capitalism, working together hand in glove. That is a challenge, but it also provides a focus for organizing.

We then have to ask: What does the Latin American left have in its arsenal politically, and what forms can the opposition take? The great strength of the Pink Tide movements over the last quarter-century has been their electoral success in welding together disparate coalitions of people behind an anti-neoliberal project.

I hesitate to use the word “opportunity,” in view of the suffering that these developments are going to involve, but I do think that is something the Left will have to relearn: how to reassemble a somewhat different kind of progressive coalition behind a form of anti-imperial politics that is opposed to neoliberalism and to the latest twist on neoliberalism that Trump represents.

In the short term, the picture looks rather bleak, but the more the Trump strategy plays out on the ground, the more we will see opposition and resistance emerging, and the more difficult it will be for the US to secure its desired outcomes by force. Over the long run, I do see a pushback happening, but it’s going to take a while for the Left to work out how exactly to do that and what the viable electoral path to that goal is.