Establishment Dems Are Pushing Gentrification, Not Socialists

Centrist Democratic leaders like Hakeem Jeffries have taken to calling socialists “Team Gentrification.” Strange, since those same establishment Democrats take real estate cash while socialist candidates like Zohran Mamdani fight for affordable housing.

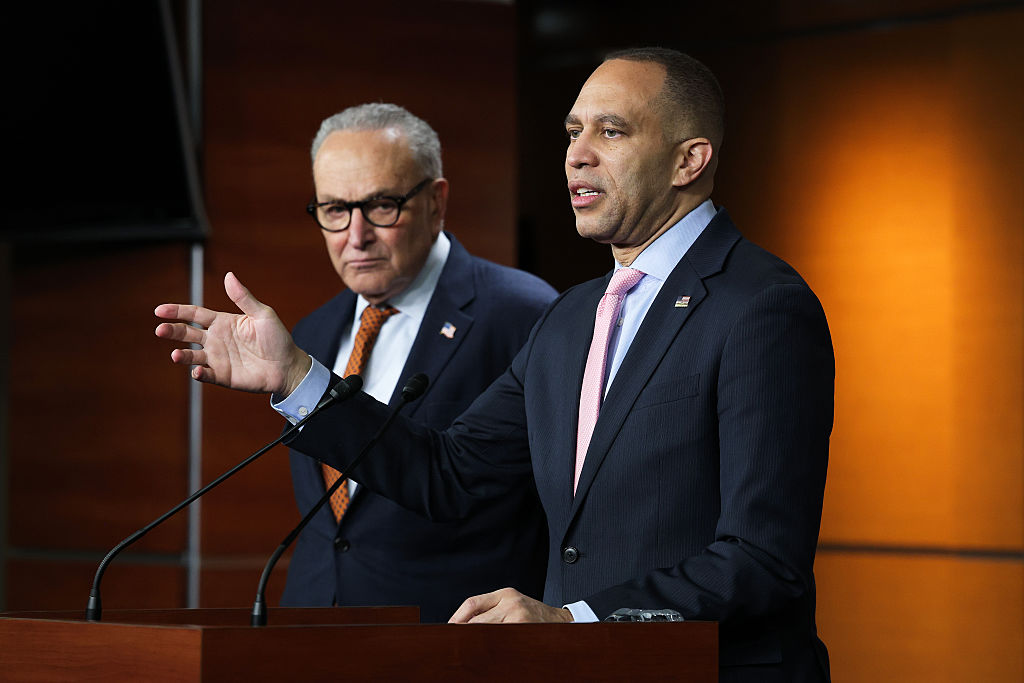

NYC-DSA’s electoral success has been attributed to gentrification by critics in the Democratic establishment. The irony is that politicians like Hakeem Jeffries have nobody to blame for that gentrification but themselves and their real estate donors. (Kevin Dietsch / Getty Images)

At Zohran Mamdani’s October rally at Forest Hills Stadium in Queens, two influential New Yorkers were conspicuously absent. In a rally that featured thirteen thousand people, including New York governor Kathy Hochul and numerous other elected officials, Hakeem Jeffries and Chuck Schumer, the Democratic leaders of the House and Senate, were not present to support the Democratic nominee of the largest city in the country that they both represent.

Jeffries had at least issued a tepid endorsement for Mamdani (though his statement included a reference to their “areas of principled disagreement”). But his initial reaction to Mamdani’s victory in June’s Democratic primary was more combative. After reports started circulating about potential primary challengers to Jeffries, his spokesperson responded sharply, telling CNN: “if Team Gentrification wants a primary fight, our response will be forceful and unrelenting.”

This cynical characterization of the movement that powered Mamdani to victory is a variation on a consistent, repeated theme of criticism from establishment Democratic politicians and elements of the press since NYC-DSA’s first primary victory in 2018. In this narrative, NYC-DSA’s electoral success is entirely due to a wave of relatively affluent, college-educated, and largely white gentrifiers moving into working-class neighborhoods, and is therefore somehow inauthentic or exploitative. This narrative conveniently erases Zohran’s overwhelming support from working-class Muslim communities, the 55 percent of Black voters who supported him in the general election, and the fact that DSA is one of the most consistent opponents of the landlord lobby.

Still, while this characterization leaves out significant parts of the electoral coalition NYC-DSA has built, it is undeniable that gentrification has contributed to the success of NYC-DSA’s electoral program over the last eight years. The irony of this criticism is that establishment Democrats have nobody to blame but themselves. From Schumer to Andrew Cuomo to Jeffries, New York’s establishment Democrats (including many born-and-raised New Yorkers) created a policy environment that privileged landlords over tenants and accelerated the very gentrification they often decry, building the “Commie Corridor” that would eventually shake the foundations of their power.

The Power of the Landlord Lobby

Any discussion of the landlord lobby has to start with their flagship organization: the Real Estate Board of New York. Founded in 1896, REBNY is the premiere vehicle for turning rent checks into lobbyist cash and pro-landlord legislation. For decades, it enjoyed an unquestioned position of power in Albany that has only recently been challenged by the 2019 Housing Stability and Tenant Support Act.

This legislation, which was pushed through by a tenant coalition called Housing Justice for All, made rent stabilization permanent instead of expiring every four years, allowed upstate cities to opt into rent stabilization, and closed loopholes that landlords had used to take hundreds of thousands of units out of rent stabilization coverage. The industry has responded with prodigious litigation, even attempting to challenge the constitutionality of rent stabilization itself at the Supreme Court.

This ongoing tug-of-war between landlords and tenants was dramatized by last year’s REBNY gala, an annual fixture of the city’s political calendar that regularly draws political bigwigs and elected officials. Schumer, Jeffries, Hochul, and much of the rest of the city’s political class were in attendance, prompting Hochul to quip: “Is there anybody who’s an elected official who’s not here tonight? You’re missing a damn good party, that’s all I can say.”

There was at least one elected official who was not in attendance. As many of his colleagues in government glad-handed inside and Hochul crowed about her “close relationship with REBNY,” Zohran Mamdani, then a little-known longshot candidate, joined tenants with the Housing Justice for All coalition protesting outside in the cold.

Gala attendance notwithstanding, it’s clear that Jeffries, Schumer, and the New York Democratic Party establishment are happy to accept real estate contributions. From 2019 to 2024, the real estate industry provided Schumer with over $2.5 million, making it the third-highest industry donor to him after law and finance. In 2024 alone, Jeffries received over $800,000 in real estate contributions, making it the fourth-highest industry donor after finance, law, and the pro-Israel lobby.

Who’s Really on “Team Gentrification”?

It’s true that New York City is in dire need of additional housing. Mayor Mamdani has said that he now believes that private developers must play a role in alleviating the housing shortage and appointed several real-estate industry heavyweights to transition committees (where they will no doubt argue with the tenant advocates also included on those committees).

Still, the story of post-1990s housing policy in New York City is largely a story of deregulation, capitulation to the real estate industry, and widespread upzoning without significant protections for working-class communities. Policies like federal and state government divestment from public housing and taking hundreds of thousands of units out of rent stabilization reduced the supply of livable, affordable units. At the same time, efforts to increase unit supply through upzoning, a change that allows for local zoning laws to build higher-density housing, have largely failed to control rents when pursued without strong tenant protections. Mayor Michael Bloomberg upzoned 40 percent of the city, while median rents rose by 19 percent and the homeless shelter population grew from thirty thousand to fifty thousand a night. Even Bill de Blasio’s attempts to bake affordability into our zoning regime through Mandatory Inclusionary Housing were ineffective at addressing the crisis.

De Blasio’s efforts are illustrative in this regard. Mandatory Inclusionary Housing allows upzoning sought by developers in exchange for a binding commitment to reserve some units as “affordable” housing. The rub is that the thresholds are not based on the income of the neighborhood, but on the income of the region, including Westchester, Putnam, and Rockland counties. Using this measure, the “median” income in New York City is $108,700 for a one-person household.

So you can imagine what happens when you use this framework to upzone, say, East New York, which has a median income of $51,000 per person. Working-class families are displaced as landlords are incentivized to raise rents, drive out tenants, and flip their properties; speculators are incentivized to aggressively pursue working-class families’ properties and even commit deed theft, and new groups of higher-income people move in, funneled into working-class communities of color by policies beyond their control.

This reality is why the “Team Gentrification” critique rings hollow. The true “gentrifiers” are not the individuals seeking housing wherever they can find it, but the developers and allied politicians who create the policy environment underlying this rolling cycle of displacement.

A Coalition for Affordable Housing

Still, there is hope. The political establishment did not predict how these new residents would act politically. Instead of seeing themselves as “temporarily embarrassed millionaires,” as might be expected due to their class background, many of them found common cause with their working-class neighbors. They correctly understood that the process of displacement would eventually come for everyone.

This understanding came not just from altruism or ideology, but from rational self-interest. While past generations of would-be yuppies could rest assured that homeownership and retirement was in their future, millennials are the first generation in modern American history who are worse off than their parents. The oligarchs who redistributed as much wealth as possible upward and stripped postwar welfare capitalism for parts unwittingly created a massively indebted but skilled and well-educated cohort of downwardly mobile radicals with little stake in neoliberal capitalism. After being put in close proximity to dispossession, displacement, homelessness, and poverty, they organized with their neighbors into tenant unions, supported pro-tenant politicians, and over time became a key part of a cross-class, multiracial political movement that unexpectedly elected New York City’s first democratic socialist mayor in the modern era.

This achievement carries with it opportunities and pitfalls. Will the Mamdani administration be able to deliver on its promise of two hundred thousand 100 percent affordable union-built apartments? And will “affordable” mean affordable for local residents, or will he repeat de Blasio’s mistakes and fuel further displacement? Will Mamdani successfully outlast pressure from the landlord lobby and manage to eke out impactful pro-tenant policies within a challenging environment? Or will the powerful forces of high finance and real estate capital that have bent the ear of so many of our elected leaders prove too strong?

Mamdani’s first few weeks seem to indicate that his ear remains unbent. On his first day, he visited with the Union of Pinnacle Tenants, a tenant union created to organize tenants whose buildings are owned by billionaire Joel Wiener’s Pinnacle Group. He examined unlivable conditions caused by Pinnacle’s business model, which previously relied on taking out risky loans to buy rent-stabilized buildings, refusing to maintain them, pressuring tenants to leave through harassment, then deregulating units through vacancy or renovation. The loopholes that made such a predatory business model viable were closed by the 2019 Housing Stability and Tenant Protection Act — prompting Pinnacle to further neglect its properties, declare bankruptcy, and pursue a sale to another corporate landlord.

Mamdani directed the city’s law department to join the tenants in attempting to block the sale, potentially opening the door to the tenant union’s preferred outcome of a Community Land Trust or other alternative ownership structure. While a federal judge blocked the move for now, this was a swift decision taken to support a tenant union against a billionaire landlord, and it is still unclear what the final outcome will be.

Another telling decision Mamdani announced on day one, in the Pinnacle apartment building’s lobby, was his appointment of accomplished tenant organizer Cea Weaver as director of a revitalized Office to Protect Tenants. As a pivotal driving force for the 2019 housing laws with a long history of organizing tenants directly as well as building Housing Justice For All, a statewide tenant advocacy coalition, Weaver is arguably the real estate industry’s most feared and formidable enemy. (Full disclosure: I have worked with Weaver on various housing campaigns over the years.)

Upon appointment, several of her old tweets were unearthed and publicized widely due to their controversial content. In one tweet, Weaver referred to private property and homeownership as a “weapon of white supremacy,” no doubt referencing the well-researched connection between previous racist housing policies and the resulting racial home equity gap. Weaver was the target of a coordinated attempt at character assassination, with right-wing figures around the country attacking her online and reporters camping out at her apartment building. Still, Mamdani stuck with her, citing her extensive body of work as a tenant organizer and advocate and showing that he would stand by the organized tenant movement in New York State.

That movement grew through forming bonds of solidarity between existing residents and relative newcomers, both threatened by the cycle of displacement. Cities across the country are exhibiting similar housing transformations, as historically working-class neighborhoods are transformed with rising rents, eagerly aided by establishment politicians. “Commie Corridors” are forming in other cities, as young people inclined to radical politics find themselves at the mercy of their landlords and find common cause with their neighbors. Cities like Chicago and Minneapolis have growing democratic socialist caucuses in their city councils, Seattle democratic socialist Katie Wilson just won an upset mayoral victory, and even in Atlanta, DSA activist Kelsea Bond won a landslide election to represent the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Midtown.

While this process of change is still in its infancy, skeptics would do well to remember how far this movement has come. In less than a decade, democratic socialism has gone from a fringe curiosity to winning the mayoralty of America’s largest city. I hope that Democratic leadership will take notice and realize the power of tenants and workers over landlords and corporations, but I’m not holding my breath. Chances are, they will continue to schmooze with the titans of industry inside while our movement pickets outside in the cold.

Still, things can change quickly. It would behoove leaders across the country to forgo the real estate industry’s canapés and champagne and spend more time listening to the tenants whose rent checks paid for them. Otherwise, they might not find themselves our leaders for long.