Max Beckmann, an Unintentionally Political Artist

German artist Max Beckmann is often regarded as interwar Germany’s foremost apostle of despair. Yet while he emphasized his own apolitical character, his work was also the product of a spiritual foreboding that never escaped politics.

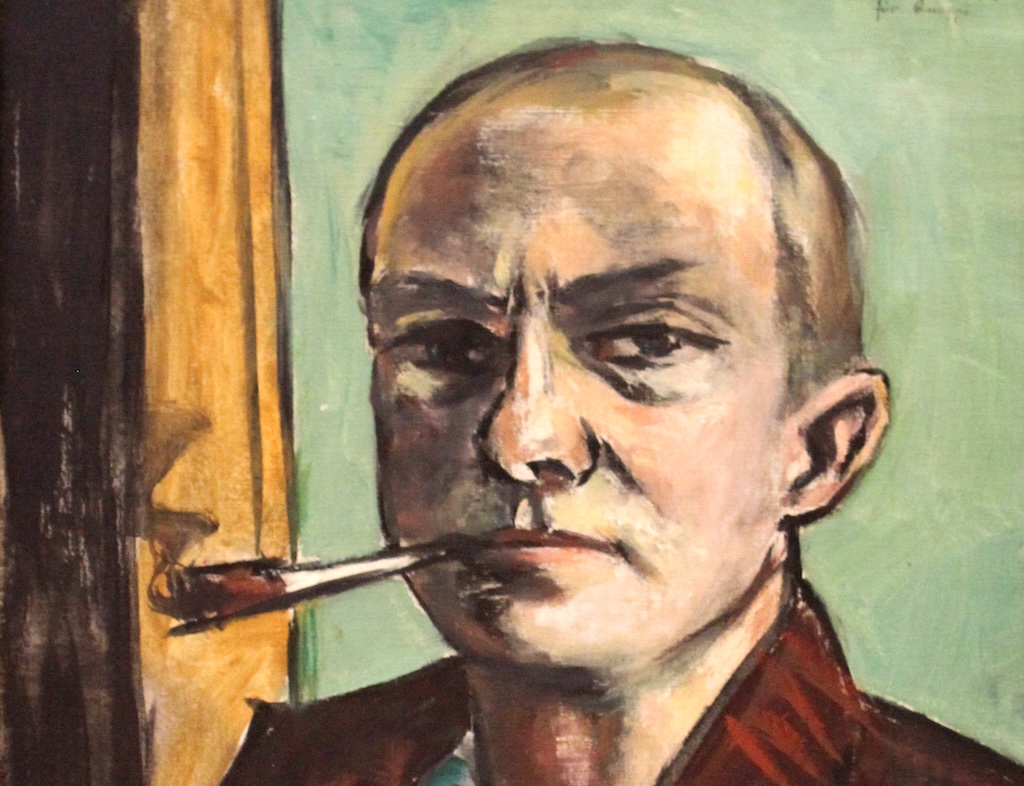

Max Beckmann, Selbstbildnis auf Grün mit grünem Hemd [Self -portrait on green with green shirt], oil on canvas, 1938. (cropped)

Max Beckmann “never busied himself with barricades” — or so he claimed. The German painter and printmaker insisted he was apolitical. “I have only tried to realize my conception of the world as intensely as possible,” he explained in 1938 from exile in Amsterdam. “Painting is a very difficult thing. It absorbs the whole man, body and soul — thus I have passed blindly many things which belong to real and political life.”

Passing blindly by was an objective he maintained throughout his tumultuous career. But as a new retrospective at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum shows too well, it was one that he never quite fulfilled. Long cast as interwar Germany’s foremost exponent of despair, Beckmann’s particular style is better understood as a product of a distinctly spiritual foreboding that could never escape politics.

Born into a middle-class family in Leipzig in 1894, Beckmann had a typical bourgeois upbringing until age ten, when his father died. After art school in Weimar and a spell in Paris, he established his practice in Berlin. Here, he found early success under the influence of the Berlin Secessionists, who rebelled against the restrictions on artistic production imposed by Kaiser Wilhelm II. It should have served as an early warning that there is no such thing as the apolitical artist. As well as large theatrical scenes, he honed his skills as a draftsman. Though his prints are renowned for their pioneering and experimental compositions, Beckmann was not a formal innovator. He used the traditional mediums pioneered in Germany in earlier centuries: drypoint etchings, lithographs, and a small number of woodcuts.

Beckmann was not among those expressionists such as John Heartfield, George Grosz, and Käthe Kollwitz who became early opponents of World War I. Instead he enlisted as a medical orderly with enthusiasm, hoping it would bring new inspiration for his art. Yet in Dead Man Laid Out (1915), we see how his perspective was reshaped by the hideous dismemberments and shell shock that he witnessed. A corpse is truncated into a set of contortions, with deep pencil lines suggesting a tension in the artist’s own hands. Beckmann’s determination to objectively depict the body’s interior as well as exterior left him with no choice but to put the savagery of war center stage.

The Städel Museum’s interest in Beckmann is no coincidence. The artist came to Frankfurt after he was discharged from the military, having suffered a nervous breakdown in 1915. Ten years later, he was appointed to lead a fine art master class at the municipal school of arts and crafts. His work was displayed in eighteen solo and group exhibitions in Frankfurt up until the Nazis came to power in 1933. This show’s focus on Beckmann’s drawings, often the first drafts of much-vaunted paintings and prints, puts the spotlight on both his creative process and his uneasy political development. An early sketch for Resurrection, a painting Beckmann started in 1915 but never finished, is a scene of disarray, its figures huddled and frenetic. But a 1918 etching from the same project is dominated not just by bodily distortion, but by cold negative space. Its true horror is not in chaos but in order.

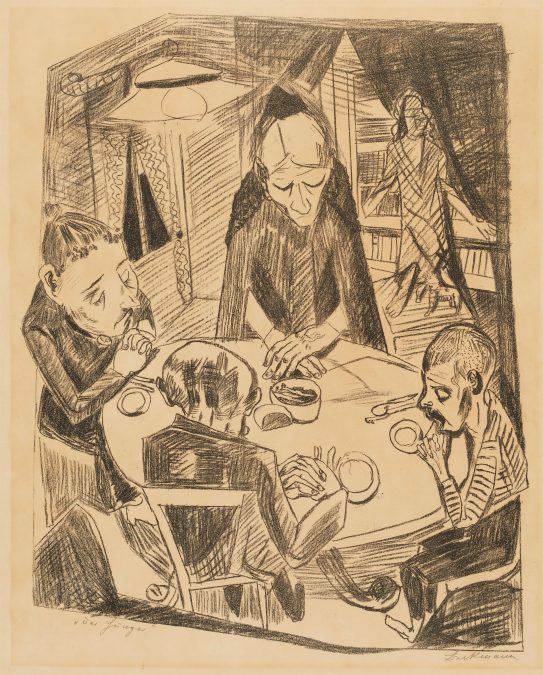

We also see how in Beckmann’s mind’s eye, the material basis of his subject matter fought with the urge to prize open the human condition. The 1919 narrative lithographic series Hell, perhaps Beckmann’s most famous work, frames nine scenes of the war’s aftermath, including the murder of communist leader Rosa Luxemburg during the Spartacist uprising. Its frontispiece is a self-portrait of Beckmann as circus master, promising a rollicking ten-minute journey through societal decay — or our money back. At the Städel, we only see the penultimate plate, “The Last Ones” — an interior scene of socialists fighting to the bitter end, as hope dissipates. But a rare first version of the print shows that its events were originally placed outdoors, its darker tones heightened by loud inscriptions that nod to both agitprop and biblical imagery. Ultimately the metaphysical triumphed over the propagandistic, and the words were dropped from the composition. But the finished product — its artillery more prominent than its scattered human forms — still has a distinctive aftertaste of the polemic.

Non-Expressionist Expressionism

Expressionism was a product of imperial Germany that would later be the subject of fierce evaluative debates between Eastern European Marxists. It persisted into the 1920s but was rejected by many of its former adherents. As early as 1918, Max Weber described it as a “spiritual narcotic.” As the conflict and the economic crises of the early Weimar Republic gave way to relative stability after 1923, Beckmann attached himself to a new movement. The Neue Sachlichkeit — “new objectivity” — was, the historian Peter Gay puts it, a search “for a place to stand in the actual world.”

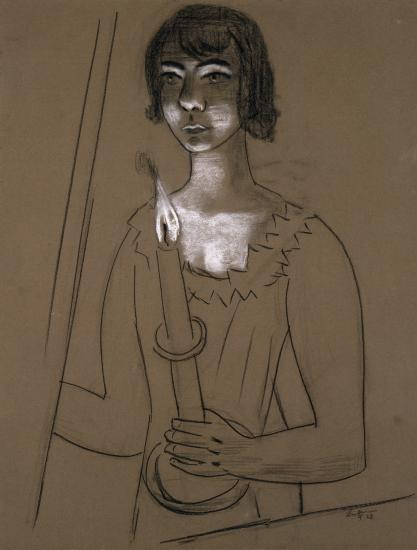

For Beckmann, it offered a return to the standpoint he had striven for throughout his career — cold and detached but perpetually stimulated by both human anatomy and the material world. His works from the mid- to late 1920s are his most domestic, though their emotional distance means they retain a certain skepticism toward bourgeois existence. In Quappi with Candle (1928), he uses black pencil and white gouache to create a heightened sense of darkness in what remains a thoroughly minimalist work. The figure, his second wife Mathilde “Quappi” von Kaulbach, would seem ghostly were it not for her unusually muscular arms. We see her in totally different dress — and demeanor — in Quappi with Playing Cards (Patience) (1926) where her unusually long fingers draw our eyes — and seemingly hers, too — to the card table, which is tilted towards the frame. Like Beckmann’s own appearance in the frontispiece of Hell, Quappi plays the role of host — not in hell, but in her own parlor.

It was not to last. A professed disinterest in politics, and even the fascist ardor of a minority of expressionists (notably Emil Nolde), was no passport to being left alone by the new political order. Though Joseph Goebbels had retained his youthful enthusiasm for expressionism, seeing it as the essence of an indigenous Nordic spirit, he quickly fell into line with the suspicion of modernism that dominated the Nazi party. After Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Beckmann was driven out of Frankfurt’s Städelschule.

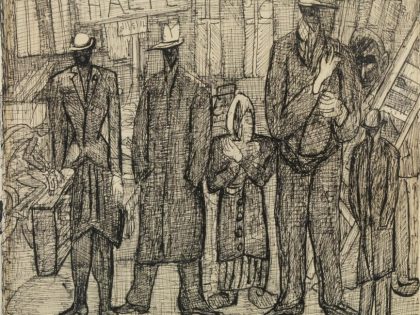

From exile in Amsterdam, Beckmann’s career entered its most prolific period, and his works took on a new emotional intensity. The German invasion of the Netherlands made his attempts to obtain a US visa even more desperate, but he was not granted one until the war was over. “The world is rather kaput,” Beckmann wrote to his friend Stephan Lackner in 1945, “but the specters climb out of their caves and pretend to again become normal and customary humans who ask each other’s pardon instead of eating one another or sucking each other’s blood.” We see a visualization of this verdict in Tram Stop (1945). Like the more impressionist Evening Street Scene (1913) earlier in the show, it’s a rare excursion outdoors – only this time it’s heavy with a granular darkness of pen ink. Its faceless, elongated and grotesque figures radiate both shame, denial and continued threat. At the margin, a single distorted face peers over a ladder in resignation.

US Works

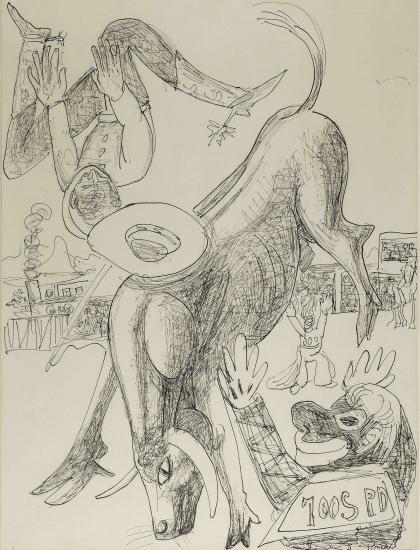

Beckmann never returned to Germany but found teaching posts in St Louis and New York. His US works suggest he had finally found sustained stability required for a practice defined by objectivity and soul-searching – though these were cut short by his death, at age sixty-six, in 1950. In Students (1947), he brings a large group to life through depicting individual expressions of character as physical attributes. Rodeo (1949) may have been his first, but it’s a study that captures a quintessential American pastime with a finesse only available to the outsider.

In his visceral critique of expressionism in 1934, Hungarian Marxist György Lukács argued that the Neue Sachlichkeit was how “the petty-bourgeois intelligentsia found their way once again to a peaceful and self-possessed emptiness” after the stabilization of the Weimar Republic. “Self-possessed” is a justified description of Beckmann, but “empty” is not. And by the time he found peace, experience had taught him that disengagement could only be a matter of good fortune — not personal choice.