Don’t Believe the Hype — or Doom — About AI

For America’s VC-dominated tech industry, AI hype isn’t just a crazy by-product — it’s a structural part of the US economy in which capital tries to write our destinies. We shouldn’t let it.

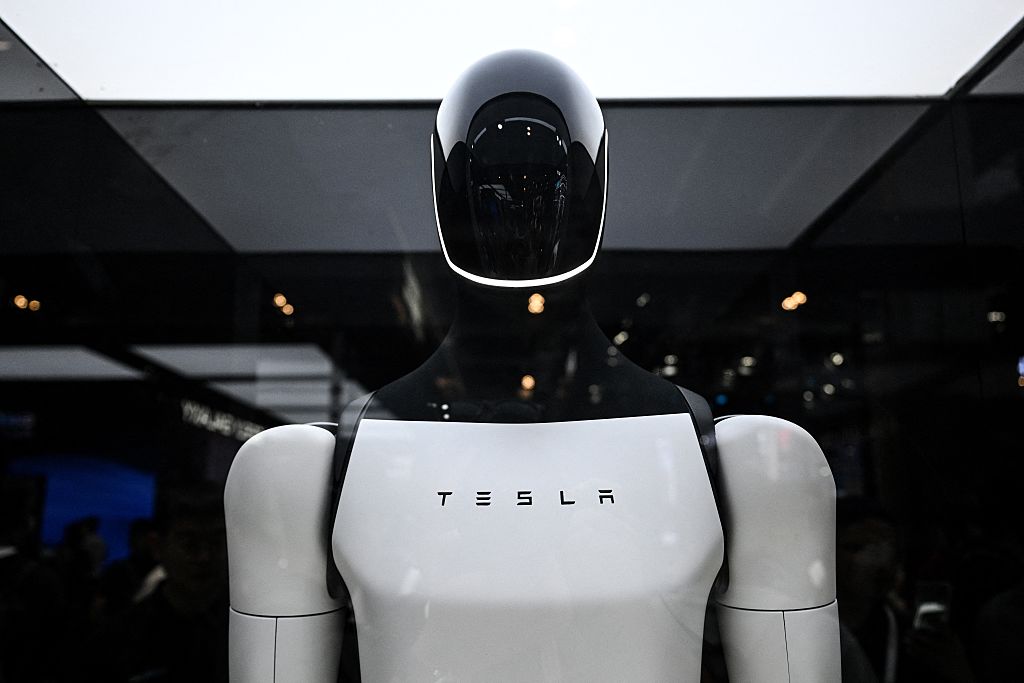

Hype is nowhere more ubiquitous than in the world of artificial intelligence. (Hector Retamal / AFP via Getty Images)

In December 2023, just as ChatGPT marked its first birthday, Politico asked Signal president and tech critic Meredith Whittaker which tech trend she thought was most “overhyped.” The role of a critic, the interviewer seemed to assume, is to draw a line between promise and reality, between hype and fact.

Whittaker, however, decided to sidestep the question. Rather than pointing to any particular technology, she suggested that “the venture capital business model needs to be understood as requiring hype.”

Today hype is nowhere more ubiquitous than in the world of artificial intelligence. From superintelligence to outer space data centers, AI certainly seems to inspire ever wilder fever dreams. Every PR stunt is followed by a debunking, and every stellar revenue prediction countered by a bubble warning, and yet the hype trend — despite recent doubts from famed short sellers like Michael Burry — seems to only go in one direction: up.

The seeming ineffectiveness of anti-hype (no matter how correct the anti-hype may be) suggests that Whittaker’s little sidestep is important. Instead of playing whack-a-hype-mole, she suggests that the aim of critique should be “understanding the growing chasm between the narrative of techno-optimists and the reality of our tech-encumbered world.” The promises of a technology differ from its real effects, and the gap between those two seems to grow ever more pronounced. Surely hype, PR, and constant over-promising are part of this.

But is hype all there is to the chasm? And why is there a chasm in the first place? Why, Whittaker encourages us to ask, are the promises of technology always so loud and always so hollow?

“Hype” Is a Structural Part of the American Economy

In Whittaker’s framing, hype isn’t so much about particular technologies, start-ups in general, or even Silicon Valley culture overall, but it is inherent to a particular way to reinvest past profits: venture capital (VC). In other words, the production of hype is a question of political economy.

For every piece of hype that Silicon Valley produces, there is a well-formulated critique of it out there. Indeed, criticizing particular companies for particular actions is part and parcel of liberal media discourses. At the same time, criticizing the overall power and incentive structure of capitalism (the game that these corporate players play) is all too often beyond the pale. When it comes to hype, we can see the same asymmetry. Critiques of hype abound, especially around AI.

But we need critiques not just of the moves and players but of the game itself. If we want to figure out what to do about the chasm — how to avoid a coming techno-dystopia — we need to flesh out Whittaker’s argument and interrogate the political economy that produces both the hype and the chasm.

So, let’s take Whittaker’s suggestion and ask just why exactly VC runs on hype. First of all, the VC investment model is all about early-stage businesses, about financing start-ups. It’s generally expected that most start-ups will fail, but VCs hope that a small percentage will become valuable enough to more than make up for it. The bet is, essentially, that a few start-ups turn into the rare and magical “unicorns,” defined as companies valued at more than a billion dollars. Of course, most of the promised and hoped-for future unicorns turn out to be mere mules. This is the basis of the business model, and presumably neither start-up founders nor investors in the VC space are confused about it.

Where does the hype come in? Insofar as VC is about betting on the future, it is by definition trading in speculations. After all, the future is not a thing we can empirically ascertain — we can only make more or less educated guesses. Equally obviously, sales pitches are never neutral. They’re supposed to attract buyers/investors and drive up the price. So, sales pitches are, by their very nature, positive spins. As everyone knows, it’s easier to imagine winning the lottery than to actually win. Blend the imaginative license of the future with the rosy-spin nature of advertising and you have the perfect recipe for hype creation. There’s no ceiling on the optimism — they can be as positive as the sellers can get away with. And when the VC hype engine meets a techology like AI, it’s the perfect storm. Soon, we’re told, there will be a technology that will solve all the problems you could possibly imagine, and then some that you haven’t even thought about.

Now, it is crucial to keep in mind who that hype is directed at: investors who are hoping to buy choice cuts of a future unicorn on the cheap. Of course, others may hear the sales pitch, too — if you can get a journalist to repeat your pitch, all the better. The hype-machine is leaky. It drips and we all get splashed with it, whatever kind of stakeholder (or even bystander) we may be. Possible future customers and potential users are all subjected to the dreams and nightmares generated by Silicon Valley and its VC ecosystem.

Given the prevalence of hype, it should come as no surprise that so many critiques of Silicon Valley and big tech start by simply flipping the sign from positive to negative: calling the advertisement a lie and pointing out hype and exaggerations. Clearly, that is what Politico was after from Whittaker — they wanted her to denounce particular lies, products, or companies.

Like Whittaker, we think it’s worth pushing back on that impulse a bit. In fact, we think that calling out hype is, for the most part, an ineffectual way of speaking truth to power. Surely some of the popularity of anti-hype takes is about those product adoption pitches we mentioned. This is especially true with AI. Many people are frustrated by the rapid push toward artificial intelligence, and as a result, they’re actively looking for tools they can use to push back against it. Calling the adoption pitches “hype” — or its more intense cousins like “scam,” “con,” “snake oil,” etc. — provides a kind of psychological weapon. It also brings in an emotional valence, which helps to energize people by evoking an ethical dimension that “exaggerated sales pitch” or “advertisement” do not.

There also is an obvious truth to it — calling a lie “a lie” can be potent. We are constantly bombarded with the claim that this or that tech future is inevitable. Clearly, that’s a lie, and a lie meant to get us in line and weaponized against humanity. It is certainly worth refuting. There is always an alternative future that we can build.

Unfortunately, tech critiques that take up the anti-hype stances are rarely as clear and careful as Whittaker about where the hype is coming from, why it’s inherent to venture capital, and who its primary target is: investors. This is perhaps even more obvious when “bubble” is thrown into the mix. After all, warning of a bubble is primarily a call to investors to redirect their money flows. We do not believe that the work of tech criticism is about warning investors. They are, after all, part of the very VC ecosystem that generates the hype — the ones who are inflating the bubble in the first place.

What Is a Political Theory Even For?

Calling a sales pitch “hype” draws an implicit line between the ones who tell lies and the ones who are being lied to, producing a rather odd political grouping: certain companies (say, OpenAI) are liars. And bosses who adopt AI, AI investors, and the users and workers that AI is foisted upon are all cast in the common role of victims of hype and scams.

What’s so wrong about grouping together all those on the receiving end of hype, from investors to bosses to workers? The fact is that the whole chasm between the promises of technology and the dreadful tech realities is very much about class. When the hype rings out, investors and bosses hear promises. But those very promises constitute threats to everyone else. Let’s look at two illustrative examples.

One promise — or threat — is that AI will automate surveillance and discipline labor. We see that promise everywhere today. Take, for example, Amazon’s warehouses, where video classification AIs are constantly surveilling and classifying workers’ most minute actions. Oversight, management, and control are now increasingly driven by AI. Often, what looks like automation is really more accurately described as industrialization: AI requires workers that label data to correct and train the algorithm. Or, to put it the other way around: The algorithm enables these often underpaid data workers to produce oversight at an industrial scale and in a way that makes none of them into a manager.

We can look for similar effects in the political realm, where the state department is using AI to mass scan social media posts, in order to revoke visas of those who engage in the “wrong” kind of speech. Because AI surveillance can expand to ever larger scales, it creeps into ever smaller nooks and crannies of work and life. Here we see the chasm yawning between those subjected to the algorithm and those whose bidding it does.

A second promise — or threat — is that AI will, to quote a social media post, “allow wealth to access skills, while removing from skill the ability to access wealth.” In other words, AI (and in particular generative AI) is an attempt to transfer knowledge into tools, and that attempt is about shifting the control of skills from workers to capital in order to depress wages. In Why We Fear AI, we call this “techno-Taylorism,” after the scientific management school founded by Frederick Winslow Taylor. Taylorism (and its many offsprings) are all about centralizing knowledge of labor processes among management. Having gathered such knowledge, bosses can divvy up work and parcel out tasks in accordance with capital’s needs. Chief among those is reducing to the absolute minimum costly labor that requires special training.

The techno-Taylorism of AI differs from classical Taylorism simply insofar as knowledge is transferred not to a managerial apparatus but directly into a tool. The point, of course, is the same: to transform work so that overall wages can be reduced. We can already see this process at play across sectors. From translators to coders, jobs are cut, only to reemerge as gig work. Here, newly precarious workers have to gussy up AI slop for less pay, with fewer benefits, and with even less job security. A penny saved is a penny earned, as the saying goes — and the promise of AI is that the penny comes out of our pockets.

Taylor himself would undoubtedly have been enamored with this technological development. The AI boosters may speak of productivity increases but Taylor understood that the only thing capital (and its ledger books) care about is labor costs per unit output. Capital can indeed decrease those costs by increasing productivity. But it can also decrease those costs by reducing not the labor time needed but simply its cost to capital by depressing wages. One may be socially desirable (more goods in less time) and the other one may be a force for immiseration (less pay in the same amount of time) — but to capital they’re basically the same thing.

This is key to understanding Whittaker’s chasm between the promises of technology and its real effects. We are promised productivity increases with all their implications of prosperity, leisure, and abundance for all, but what we get is a tool of class power, used to surveil workers and devalue our skills. Why does VC produce this particular discrepancy between promise and reality? Because, like all capital, it sees the world through ledger books. There is no chasm, as far as they’re concerned — their wage costs are reduced and all the numbers are in the black. They literally can’t tell the difference.

How to Talk About AI Without Falling Into “Hype” or “Doom” Camps

So, how should we talk about AI? How do we connect the discomfort, distress, and distrust that AI produces among so many people to Whittaker’s chasm? How should we discuss the quite general feeling that something’s gone terribly wrong, that technology always promises heaven and invariably produces hell instead?

The point, of course, should be to change things. And, in an odd twist, the algorithms that enable the automated production of bullshit and propaganda can be quite clarifying as a social phenomenon. AI makes the fact that technology is about power viscerally obvious. Present-day AI exists in service of the few and against the many.

We should talk about the “intelligence” of AI as the kind that is gathered, and not the kind one possesses. From classificatory AI systems for surveillance and control to generative AI systems aimed at centralizing knowledge within algorithms, the gathering and privatization of knowledge is at the heart of AI as a techno-Taylorist project.

AI is a weapon of class war from above, and hence it makes the political line that should be drawn obvious: workers against capital. This is not the line that hype-calling draws, but it is the line that emerges when we take up Whittaker’s suggestion and look seriously at the political economy of tech, VC, and hype.

Once we think about AI as a weapon of class war, and about the chasm as simply the class divide, things become clear. We can take a strategic perspective on AI too. The fact that it is being used to “enshittify” so many sectors simultaneously — often sectors whose workers might until now have been reluctant to join the labor movement — is simultaneously a threat and an opportunity to form broad-based solidarity in terms both of labor organizing and a broader socialist politics.

Capitalism and its defenders continue to make promises for a better future marked by abundance for all, and AI is central to that. But the chasm makes clear the hollowness of their ideas — all they have to offer is technology that will be used to surveil us, depress our wages, control, and poison our minds. At its heart, capitalism has always been about making people into appendages of capital, and hence into appendages of machines. AI, as the latest turn of that screw, simply lacks the usual subterfuge.

So if all the capitalists have to offer is class war from above, if the future they promise is simply a threat, then it’s time we invent our own future, make our own bold plans, and think about a world in which technology serves us — not the other way around. A world in which we make the promises and make them come true. A world in which technology gets developed to make life richer, work more interesting, and the economy sustainable and egalitarian.

It’s time we demand that technology serve human needs, not the desire of the few to make ever more profit. It’s time that we answer class war from above with class war from below. After all, we still have a world to win.