We Need More Leftist Crime Fiction

Critics of crime fiction dismiss the genre as hopelessly reactionary, but its history tells a different story. From hard-boiled American detective novels to the explosion of Scandi-noir, crime fiction has been deeply influenced by socialist writers.

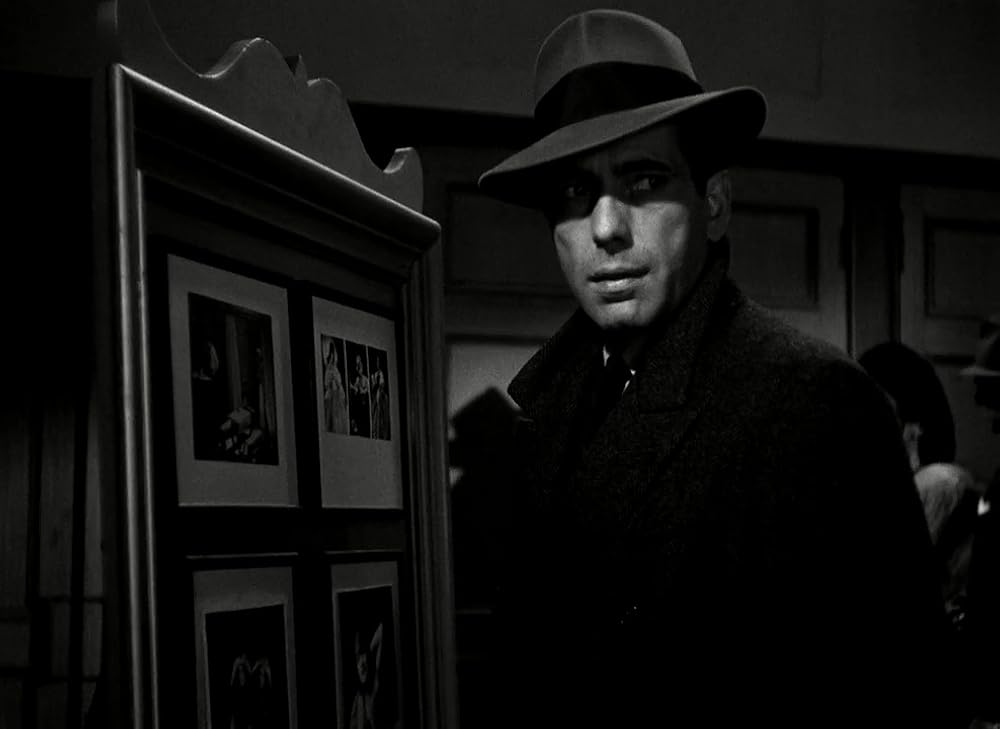

Humphrey Bogart stars as private detective Sam Spade in John Huston’s 1941 adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon. (Warner Bros.)

Crime fiction’s critics have long argued that the genre is inherently conservative. Nicholas Royle and Andrew Bennett elaborated on this in Introduction to Literature, Theory, and Criticism, noting that the genre’s strictures compel detectives to pursue individuals rather than institutions. As a result, society at large can never be the culprit, leaving less space for social critique. The story structure relies on the assumption of a harmonious status quo: a crime disrupts it and the detective is called upon to restore it by either killing or jailing someone. Moreover, crime fiction at least coexists alongside the more obviously reactionary genre of true crime, a steady diet of which convinces people that violent crime rates are perpetually soaring when they’re actually falling, eroding social trust and breeding reaction.

This case is only straightforward if we overlook American detective fiction’s leftist and socially conscious roots. Dashiell Hammett did as much as anybody to invent the modern detective novel through classics such as Red Harvest, The Maltese Falcon, and The Glass Key. But Hammett had started his career working for the Pinkerton Detective Agency, and watching the agency serve as muscle for mining magnates and other captains of industry deeply disillusioned him. Hammett claimed that he had even been approached to help murder an IWW leader in Butte, Montana. He spent the rest of his life on the Left, joining the Communist Party and being blacklisted during the McCarthy Era.

In Red Harvest, the unnamed detective known only as the Continental Op is invited to the town of Personville to eradicate gangs creating chaos there, only to discover that the newspaper editor who invited him has been murdered. He’s left to deal with the town’s reigning mining magnate and father of the murdered editor, Elihu Wilsson, who is revealed to have initially invited the gangs in to break up a labor dispute years before. The police are corrupt, and the gangs are in and out of favor with city hall. The Op manipulates them into killing each other off before summoning the feds to restore order.

Hammett was writing at a time when municipal law enforcement was deeply and routinely corrupt, almost comically so. In many major American cities, the lines between city government, the cops, and gangs were so blurred as to be effectively meaningless. Capitalists like the fictional Wilsson had at best lost control of forces they had unleashed. But the Op (and Hammett by extension) is skeptical that even with the gangs destroyed, anything will change for the better. With the feds coming, the Op remarks to Elihu Wilsson, “Then you’ll have your city back, all nice and clean and ready to go to the dogs again.”

Hammett wasn’t unique in this regard: detective fiction or crime fiction has always hosted writers on both sides of the political spectrum. To cite one example, Kenneth Fearing is famous for The Big Clock, an innovative multi-perspective novel about the editor of a crime fiction magazine trying to solve a murder. He was active in left-wing circles, particularly as a member of the John Reed Club, named for an American socialist chronicler of the Russian Revolution. When subpoenaed during the McCarthyist anti-communist crusades and asked whether he was a member of the Communist Party, Fearing replied, “Not yet.”

The hard-boiled crime writer Jim Thompson was a member of the Communist Party in the 1930s and infused his novels with the perspectives of working-class people who had been chewed up and used by the capitalist system. Rex Stout, author of the Nero Wolfe series, was one of the founders of the influential Marxist magazine New Masses. Though he distanced himself from Communism, he openly opposed the blacklisting tactics of the McCarthy era.

Not only were progressives and leftists writing crime fiction, but it was seen as an appropriate and respectable use of their time. And far from posing an intractable conflict, the genre seemed tailor-made to their worldview. Raymond Chandler’s politics were less firmly established than Dashiell Hammett’s, but the themes he returned to again and again were corruption, class conflict, and the social origins of crime. His detective Philip Marlowe is perpetually suspicious of the powerful and the guardians of so-called order. Marlowe gets knocked around by the actual cops plenty in Chandler’s stories.

A skeptic might be tempted to chalk this up to the unique circumstances of 1930s America. Not so. This tradition of socially conscious crime fiction transcends that particular time and place. Today, Scandinavian noir has become a global phenomenon thanks to works such as Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Larsson was himself a left-wing activist: he trained Marxist guerrillas in Eritrea in mortar use in the 1970s and later founded the Swedish Expo Foundation, which researched right-wing extremism in Sweden. Henning Mankell, whose Wallander series is one of the best-known examples globally of “Scandi-noir,” became involved with left-wing activism over the liberation movements in Southern Africa and later Palestine.

Scandi-noir’s origins can be traced back to two seminal figures: Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö. Wahlöö was a Swedish crime reporter who disdained writers like the “king of pulp” Mickey Spillane and the increasingly conservative turn of American crime fiction in the 1950s, with its focus on violence and sexual sadism as the chief plot devices. Wahlöö was a committed member of the Communist Party by the mid-1950s and met like-minded crime writer Maj Sjöwall in 1961. They wrote ten novels in the Inspector Beck series together, as well as several novels separately.

The pair’s novels were suffused with Marxist aesthetics and deeply critical of the limitations of Swedish social democracy. Their protagonists were not vehicles for the pair’s own politics; they were, if anything, defenders of the current regime, not so different from most depictions of American cops. But Sjöwall and Wahlöö nevertheless used them to highlight what they believed to be wrong with society, chiefly the enduring tyranny of the capitalist elite.

Reviving the Genre on the Left

So why has leftist crime fiction fallen by the wayside in the United States today? For a contemporary take on the topic, I approached Bill Fletcher, Jr. A long-time labor leader and activist, as well as a frequent Jacobin contributor, Fletcher is also the author of a series of detective novels, the David Gomes series.

Fletcher’s David Gomes is a Cape Verdean journalist based in the United States who finds himself investigating a murder in the late 1970s. Fletcher’s influences include Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, and, from a later generation, Walter Mosley.

“One of the challenges I faced when I started writing fiction was not being taken seriously,” Fletcher says. “I should be writing about strategy and history and this and that. Writing a murder mystery was frivolous.” Why was that? Fletcher didn’t hesitate. “I think that much of the US left does not understand culture and actually disdains culture. And so the idea of cultural intervention is restricted to poetry, maybe, and song,” he says. Fletcher adds:

The notion of culture froze at about 1946. When people think of culture, they think about Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger. There’s very little effort to recognize the development of or the evolution of labor and working-class culture. . . . The group Public Enemy and their song ‘Fight the Power,’ right? It’s a song that is so relevant to class struggle. And yet, when we think about labor culture, we’re almost never gonna think about Public Enemy.

For Fletcher, writing crime fiction is an outlet, which is something he encourages all leftist organizers to have. “Writing fiction and reading fiction often helps to relax me,” he says. It’s “really important for good left activists to understand that you can’t keep going 24/7, seven days a week. You need to shift gears.”

But more than that, Fletcher believes that fiction and narrative provide an important way to connect with people at an emotional level. “That’s one thing that liberals, progressives, and most leftists don’t get,” he says. “People like stories. I don’t mean just like making sh-t up. I mean that what we are trying to communicate is best done through stories that touch on real-world experiences, the experiences that regular people are having, that help them put everything together.”

Fletcher understands his crime fiction as a different way to approach the topics of race and racism, which are so central to his organizing work. Cape Verdean immigrants’ experience of racism is a unique one. When they immigrated to the United States in the nineteenth century, they were listed as Portuguese citizens, but were of African descent. Their perspective is different from both African Americans and European Americans. Fletcher’s novels became a vehicle to explore those perspectives while also introducing audiences to a group and history that most people are probably unfamiliar with. Fletcher is currently working on a third novel in the series, The Man Who Lost Faith.

There are rich intellectual and political opportunities for the Left in crime fiction, as there are in many genres and art forms. As the right wing continues to transform everything it touches into a vehicle for culture war, we can no longer afford to ignore popular culture. To write it off as hopelessly reactionary is to concede the terrain.