Out After Dark With Late-Night Workers and Zohran Mamdani

New York City socialist mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani recently spent the night reaching out to workers in Queens who keep the city moving after most New Yorkers are asleep. We tagged along.

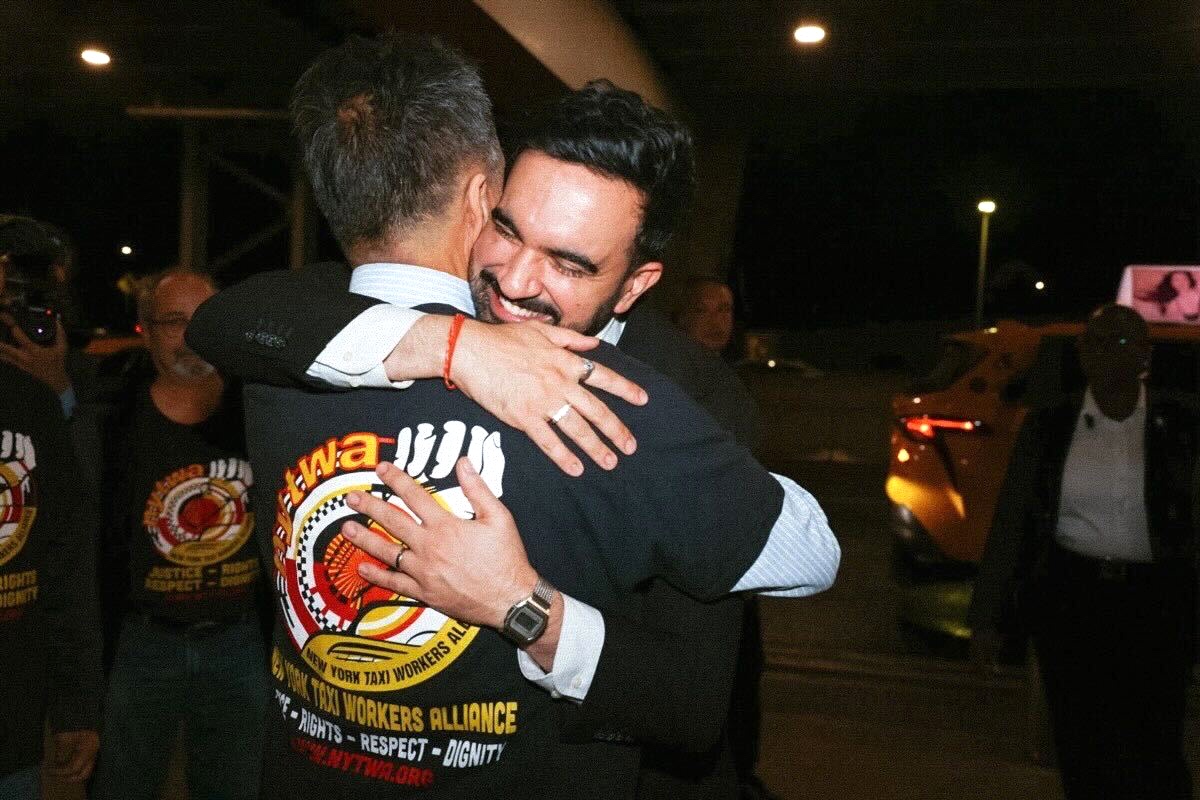

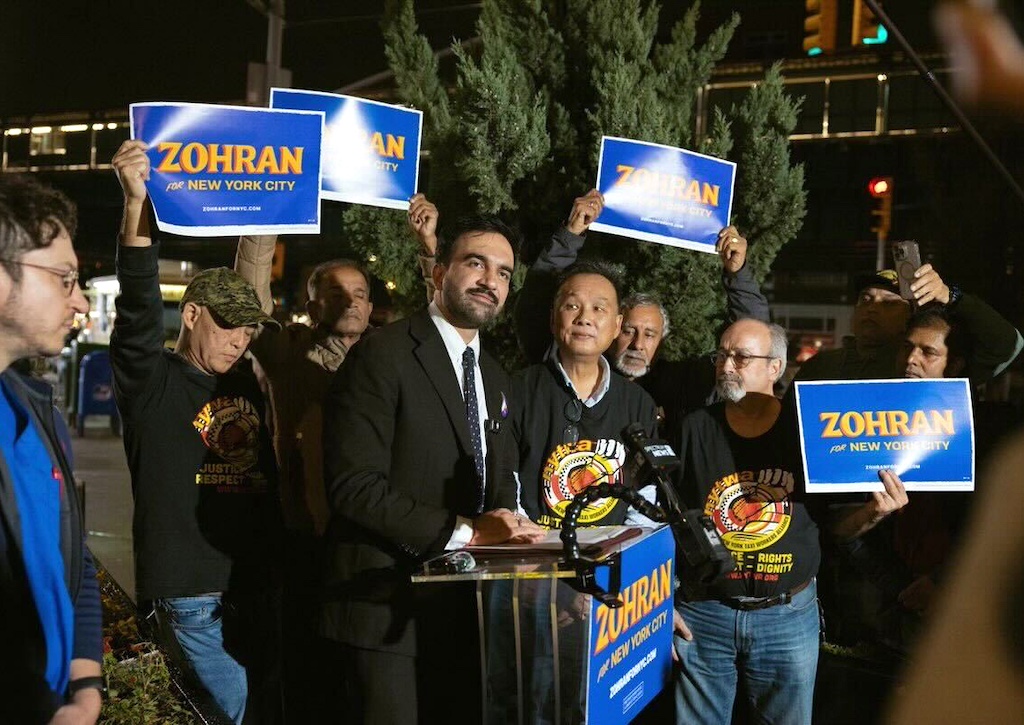

Zohran Mamdani with taxi drivers on October 30. (Zohran for NYC)

Eric Adams prides himself on staying out late. People sometimes refer to him as the “nightlife mayor” (though, in fact, that is a real position in the city that never sleeps, currently held by Jeffrey Garcia), and his line about “staying out late with the boys and getting up with the men” is repeated so frequently that I’ve seen it on T-shirts while walking around town.

What does Adams’s understanding of nightlife entail? Mostly it means going to expensive restaurants and bars — the club Zero Bond has effectively functioned as Adams’s after-hours office during his mayoral term — then mentioning those establishments by name as often as possible (and flaunting the B- and C-list celebrities he met there). Everyone who lives here knows at least a few New Yorkers like this, who are enthralled with the glamor of brushing shoulders with a celebrity and name-drop at every opportunity, who couldn’t possibly be paying for all those fancy dinners they post photos of on social media.

Yet there is a very different version of New York nightlife for many of the city’s residents, one that doesn’t make Page Six: the night shift, the workers who keep the city running and clean and healthy while the rest of us sleep. Speaking on a street corner of Jackson Heights, Queens, just before 1 a.m. on October 31, Zohran Mamdani was concerned with these New Yorkers.

“Less Zero Bond, more a mayor who visits nurses and hospitals after the sun is set, who speaks to EMS workers and bus operators working the late shifts,” he said, flanked by a group of health care workers and taxi drivers.

While the candidate is happy to visit clubs and venues — a few nights later, Mamdani would go on a barhopping get-out-the-vote odyssey across Bushwick that stretched past 2 a.m. — Thursday night was about bringing politics to workers whose schedules make participation in the campaign difficult. In the final days before the election, there was a sense of urgency in the multi-stop outing, a feeling that those with whom the candidate had organized long ago needed to be front and center at the campaign’s conclusion.

“Millions of New Yorkers live in the darkness,” said Mamdani at the street-corner press conference. He continued:

As we cook dinner and prepare our children for bed, these are the New Yorkers who lock their doors behind them and set out to work. These are the people who do not ask for special treatment, but instead, just equality. These are those who keep this city running when we arrive at LaGuardia on a red eye. These are the New Yorkers who pick us up when we carry a feverish child into the ER at three in the morning. . . . When I say that they live in the darkness, I mean that they labor not just when the moon hangs high in the night sky, but also that they are too often forgotten by those with power, their issues and concerns too often relegated to obscurity. They deserve a mayor who will not only stand with them at midnight but fight for them in the morning at city hall.

Reaching the Taxi Drivers, Again

Mamdani started with taxi drivers. At around 10 p.m. on Thursday night, he arrived at LaGuardia Airport, canvassing the lot where drivers queue and break before taking a new fare. He was joined by members of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA), an organization representing taxi drivers founded in 1998. Today the group has has tens of thousands of members including rideshare drivers, and they know Mamdani well.

“In 2018, nine drivers committed suicide, and one of my brothers was among them,” Richard Chow, a member of the NYTWA, told me as we sat at Kabab King in Jackson Heights for a late-night meal after the canvass. Back then, drivers were desperate for relief from the taxi medallion system that pushed many of them into insurmountable debt — some owed more than $500,000 — making the job not just unsustainable but a matter of debt peonage and despair.

They wanted the city to intervene and offer relief, but then-mayor Bill de Blasio “ignored us,” explained Chow, which is why some of them, Chow included, began a hunger strike outside city hall in 2021. They were joined by a handful of allies, including then-assemblymember Mamdani. After fifteen days, the NYTWA secured a deal, reducing and capping monthly payments for medallion holders, with the city guaranteeing loans in case of default.

“Ten days in, a doctor told Richard he had to start eating, and he refused,” Mamdani recounted, citing that steadfastness as inspiration during the strike’s grueling final five days.

Life remains difficult for taxi drivers, though. Many still work seven days a week to get by in one of the most expensive cities in the world. When Mamdani canvassed the drivers in the LaGuardia lot, they confirmed that reality.

“One taxi driver at LaGuardia told me that the money that he makes during his 5 p.m. to 1 a.m. shift is not enough to keep his family in their home,” said Mamdani. He pointed out that Chow, who is now in his seventies, still works seven days a week.

Health Care Workers After Dark

From LaGuardia, the campaign moved to Elmhurst Hospital in Queens. The public Health + Hospitals facility is a prime vantage point on the human toll of the city’s affordability crisis.

“Our patients often need more help than the rest, and they usually have fewer resources than the rest,” said Petar Lovric, who has worked at Elmhurst for a decade and lives nearby. “Medicaid patients who are often denied medical services elsewhere come to us.”

The facility is chronically underfunded. It was one of the first hospitals overrun by COVID-19, with the scenes of chaos inside its walls serving as a warning to the rest of the country about what was to come. Lovric gestured to the roof above us outside the hospital’s main entrance as we spoke, pointing out that the night’s drizzle was leaking through it. I could only imagine what it had been like during the morning’s downpour.

Elmhurst’s health care workers comprise an array of unions, as is often the case in a hospital. Lovric and his fellow nurses are members of the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA). District Council 37 (DC37) and 1199SEIU represent other employees, from psychologists to cafeteria workers and janitorial staff. The Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR-SEIU) represents doctors at Elmhurst. In 2023, they went on strike, the first physician work stoppage in New York in thirty years.

NYSNA and DC37 endorsed Mamdani during the primary, while 1199SEIU, representing some two hundred thousand health care workers in New York City, opted for Andrew Cuomo. As with much of the rest of the city’s labor movement, all three unions have now endorsed Mamdani in the general election.

Outside Elmhurst on Thursday night, several nurses mentioned to me that Mamdani stood with them during a 2023 contract fight over the pay gap between jobs at the city’s eleven public hospitals and private facilities, a disparity of some $20,000 — even as the city had spent $549 million the prior year on travel nurses, temp workers who receive far higher hourly pay than their unionized colleagues. To increase pressure on the city, several hundred of Elmhurst’s nurses, legally prohibited from striking, rallied outside the hospital, with Mamdani in attendance. But Lovric had met the assemblyman before that.

“I’ve been up to speak to him about Medicare for All and single-payer two or three times,” the nurse told me. “He’s been a proponent of it for as long as he’s been in office, and that’s important to me, and it’s an important issue for our patients and the hospital.”

“As a public hospital, it’s our job to take care of our patients, who might be homeless or without insurance, when they’re in the hospital. But no one takes care of them outside the hospital,” added a first-year medical resident I’d cajoled into an interview, who didn’t want to give his name, as his fellow residents, giggling over his moment in the spotlight, looked on. “It’d be great if there were more resources for homeless people. There needs to be preventative care so they don’t have to come here all the time, which would ease the burden on our work too.”

Working-Class New York’s Mayor?

It’s not hard to see how Mamdani’s agenda would make a difference for these working-class New Yorkers. A $20 minimum wage by 2030 would ease the burden on taxi drivers and Elmhurst’s lowest-paid workers alike, not to mention the hospital’s patients. Many of the facility’s staff rely on buses to get to and from work at all hours of the night, with some shelling out much of their income for the care of their own children while they care for others. What if those buses and that childcare were free?

There are other, workplace-specific elements of Mamdani’s agenda that would ease the burden of life in this city. The candidate has earned support from Los Deliveristas Unidos, an organization of app-based delivery workers in the city, by emphasizing the need to regulate gig companies rather than penalizing the e-bike drivers who sometimes speed through intersections. These platforms incentivize speed, and the workers are paid by piece rate; the violations follow from there. DoorDash has donated much to pro-Cuomo super PACs. (The strangest use of that money I’ve come across was an Instagram ad with a photo of Mamdani and Hasan Piker with bright red text over the image instructing me to Google “HASAN PIKER 9/11.”)

Mamdani has urged Amazon to recognize Amazon workers’ unions, both those formed by its warehouse workers and its subcontracted delivery drivers. When delivery drivers at several New York Amazon warehouses went on strike in December 2024, he voiced his support for them, stating, “Now the world’s largest corporation needs to stop its illegal practices, recognize the union and settle a contract with fair pay, safe working conditions, and respect on the job.”

These drivers and their counterparts across the country constitute a gigantic, misclassified workforce. The company wanted to get into the transportation business, but it did not want to deal with unions, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters foremost among them in that sector. It did so by minimizing its liabilities by using delivery service partners, or DSPs, which, in turn, employ the drivers who show up at your door in Amazon-branded vans and shirts.

It’s a prime example of the rise of the “fissured workplace,” in which a corporation foregoes employing workers directly in favor of outsourcing to smaller companies, exacerbating inequality and declining working wages and working conditions. Other workers see the effects of this exploitation: Heather Irobunda, an Elmhurst OB-GYN who spoke with Mamdani on Friday night, noted that Amazon workers sometimes land in the hospital for urinary tract infections incurred from an inability to use the restroom at work when they need one.

City Councilmember Tiffany Cabán recently introduced a bill that would force Amazon to directly employ its last-mile driver workforce, the workers who take the final stretch of package delivery. In addition to requiring delivery companies like Amazon directly employ drivers, the Delivery Protection Act would mandate safety training, make companies directly responsible for driver safety, and require last-mile delivery centers to be licensed with the city. The legislation is backed by the Teamsters, who have been organizing with DSP drivers and making the argument that Amazon constitutes a joint employer of its drivers, a status that would require it to bargain with those workers if they unionize.

Thus far, several National Labor Relations Board regions have concurred with the union’s argument, but Amazon has the capacity to appeal. Of course, the company has demonstrated that it has no problem ignoring labor law entirely and eating whatever fines it may incur. Cabán’s bill, were it to gain traction, would be met with a knockdown, drag-out fight from Amazon, which would view it as an existential threat to its business model.

Companies breaking labor laws as they please has been the order of the day for many years. Workers in the United States effectively do not have the right to organize, and rather than seeing it as the emergency that it is, an alarm that should lead them to radically change their ways, many existing unions prefer to tend to their shrinking membership even as the cost of living eats up wage gains. Too many union leaders rely on staying in the good graces of Democratic Party leadership to maintain power because it’s easier than building enough muscle and engagement among rank-and-file members to enforce power in the old-fashioned way: through collective action.

This complacency is why many of the city’s unions quickly (and sometimes undemocratically) endorsed Cuomo: Why educate your members about someone whose policies could improve their lives rather than simply go with the guy you and they already know? Unions must spend more money on organizing, and the Left must be present again and again as crises erupt in any number of industries, ready and able to make the case for organizing collectively rather than waiting for relief to come down from on high.

That brings us back to a Mamdani mayoralty. There’s plenty of risk that, should he win, people will do precisely that, investing their political agency in him and observing from the sidelines. I wonder about that when I see the pedestal some supporters place him on, as if building someone up higher doesn’t just mean they’ll have farther to fall. But it will be something of a miracle if Mamdani can realize much of his agenda: he needs state legislators and the governor to change the tax code, and the federal government can stop providing the billions of dollars in funds on which the city and state rely.

Then there is the guaranteed resistance of the city’s very rich, who will fight these policies tooth and nail. Mamdani’s supporters will have to fight this if there’s any hope of implementing his agenda. (Of the claim that the rich will leave town, evidence from the Fiscal Policy Institute suggests that isn’t the case, no matter how often the New York Post says otherwise; in fact, it is the poor who are constantly forced to leave New York because they can’t afford it. But I expect some corporations will threaten to abandon their lucrative operations here should Mamdani target them. Rideshare companies and Amazon have a history of doing so.)

While there will be many people whose political activity consists entirely of voting for Zohran, I suspect very few of them were otherwise activists who will now rest on their laurels. The question is how many newly politically engaged New Yorkers the city’s left and social movements can bring into further political activity.

The Mamdani campaign has a hundrd thousand volunteers: How many will become union organizers? This is no rhetorical question. I’ve met many people whose first political engagement was through one of Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaigns who, upon its conclusion, took jobs at Starbucks or Amazon with the intention of organizing. Labor scholar Eric Blanc’s recent research confirms these and other similar origins for union activists in many of the country’s most exciting recent organizing drives.

How many Zohran activists will the Democratic Socialists of America convert to active members? How many can be brought into the tenants’ rights or labor movement?

Being the mayor of New York City seems like one of the worst jobs in the country, a position that turns you into the scapegoat when anything goes wrong. I still don’t quite understand why Mamdani, who seems like an otherwise rational person, wants to do it. But if the movement that has grown from his campaign sticks around, putting its energy toward other endeavors, a lot can change.

Fiorello La Guardia, a key predecessor for Mamdani, spoke of the need for a “100 percent union city,” pressing for a “baby Wagner” law for New York businesses and incentivizing employers to recognize unions through a host of measures. Mamdani has similar tools at his disposal; subsidizing unionized childcare providers is right in line with his prioritization of the subject. He’ll also need to staff up the woefully under-resourced Department of Consumer and Worker Protection to enforce these regulations: the department largely pays for itself through fines and licensing, but its workforce, currently around 450 people, needs to double.

There’s also the matter of the attention a Mayor Mamdani could bring to workers’ struggles, the “bully pulpit.” His spotlight is gigantic. (Every recent profile of Mamdani mentions the media circus around him, but it’s really a shocking dynamic to experience — on Thursday night, every step he took was matched by a claustrophobically tight circle of photographers, cameras flashing in every direction.) He could use that attention to direct workers to organizing resources, demystifying unions, and introducing them to a new generation that largely still has no personal experience with organized labor.

The Difficulties of a Mamdani Mayoralty

There’s no doubt there will be contradictions in a Mamdani mayoralty, and not only in the dilemma of governing as a pro-worker mayor while unions are all but nonexistent in the city’s private sector. Most pressing may be the tricky business of handling the New York Police Department (NYPD) as a socialist.

Looking at de Blasio’s time in office is illuminating. Upon winning the mayoral race, de Blasio, who had criticized stop and frisk and advocated police reform, appointed Bill Bratton as NYPD commissioner. Bratton had held the post under Mayor Rudy Giuliani, garnering criticism for his advocacy of “broken windows” policing. But NYPD officers liked him, so de Blasio, seeking to accommodate a hostile force, brought him back.

It didn’t work out. Bratton resigned before the end of de Blasio’s first term after months of disagreement between the two. The commissioner had resisted one City Council reform bill after another — this was the first wave of Black Lives Matter protests — and his officers still hated de Blasio, turning their backs to him at a cop’s funeral in 2015. The hostility didn’t go away during his second term: in 2020, the Sergeants Benevolent Association broadcasted that they had arrested de Blasio’s daughter at a protest over the killing of George Floyd. The cops released a constant barrage of criticism and hysteria through their influence over the city’s media outlets, and de Blasio never overcame it.

Thus far, despite fearmongering about cops quitting if Mamdani wins, he hasn’t provoked much visible ire among the NYPD rank and file. In part, this may be because the department is a mess under Mayor Adams. Cops may hate Mamdani’s old tweets about defunding the police, but under Adams, they’re working forced overtime while higher-ups allegedly engage in brazen graft, generating an astonishing number of scandals.

But if Mamdani wins and moves to eliminate the Strategic Response Group, the widely reviled and legally expensive force created by Bratton in 2015 that shows up at protests, and the department’s gang database — his two concrete policing proposals, along with diverting mental health calls to a new Department of Community Safety — he could have a revolt on his hands.

His decision to keep billionaire heiress Jessica Tisch, an opponent of bail reform and supporter of quality-of-life policing (a cousin of broken windows) as commissioner is noteworthy in this light. Unlike Bratton, she is not especially beloved by officers. It suggests a desire to appease rather than restrain the NYPD (a strategy that did not work for de Blasio). It may equally be an appeasement of the city’s elite, the business class, and power brokers who are panicking not just about having Mamdani in office but over the fact that he will be hiring people they do not already know. Retaining Tisch, a competent bureaucrat and known figure, works as a salve.

Explaining Tisch’s appointment, Mamdani has said that he is confident the commissioner will follow his lead. I’m not sure that will happen. Maybe he doesn’t want to pick this fight right now, preferring to retain a laser-focus on his affordability agenda, but the conflict will be unavoidable.

There is also the issue of Israel’s genocide and the Palestine solidarity movement’s criminalization. The Democratic Party will incorporate some elements of that movement for the sake of its own future, but it will not back a free Palestine, with all of what that entails. Mamdani’s campaign has been productive in putting the lie to the idea that one must be a Zionist to succeed in US politics, which opens a lane for other political figures to push on the subject, weakening the hold of the Israel lobby.

He’ll be under pressure to moderate on the issue, and, in turn, that discipline will almost certainly be applied to the anti-capitalist left when it goes further than him, either in messaging or action. But I’m glad to have someone who founded a college Students for Justice in Palestine chapter and says he wouldn’t have sicced the NYPD on Columbia University students earlier this year in Gracie Mansion, especially in a climate of rising Islamophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment.

But that is all to come. First, he must win.

Watching Zohran late Thursday night, as I considered the obstacles ahead, I couldn’t help but be jolted back into the present by the sheer improbability of what I was witnessing: in the middle of the night, a socialist mayoral candidate whose campaign now consists of a hundred thousand volunteers was standing with working-class New Yorkers on a street corner, speaking to their priorities. And he was the favorite to win! New Yorkers of all stripes couldn’t get enough of the guy! They want the future he advocates building, and they weren’t swayed by the racist attacks that have defined his opponents’ messages in the final weeks of the race. The evidence was right there on the sidewalk.

It wasn’t just the media-trained workers next to him at the podium. A crowd immediately formed, even at 1 a.m. on a weeknight. Passersby yelled out to the candidate. Supporters followed him to his car when the press conference adjourned.

As I peeled away from the crowd, a woman speaking into a phone walked near me. “He’s talking about stuff like free buses, freezing the rent. If he can even get some of that done, maybe we don’t need to leave New York after all.”