Zohran Mamdani Can Help Rebuild New York’s Labor Movement

As New York City mayor, Zohran Mamdani will have a range of options to encourage large numbers of workers to unionize — essential both for improving working-class living standards in an unaffordable city and building an organized force to win his agenda.

New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani speaks during a rally at Lou Gehrig Plaza on September 2, 2025, in the South Bronx in New York City. (Michael M. Santiago / Getty Images)

Can Zohran Mamdani make New York City a union town again?

Organized labor here is stronger than in the rest of the country. But this isn’t saying much. The unionization rate of the city’s private sector is only 13.5 percent, almost half of what it was in the 1980s. And while 61.1 percent of public sector workers remain unionized, only one in five New York City workers belongs to a union — a significant drop from the one-in-three unionization rate of the 1970s.

Turning around labor’s decline is crucial for achieving Mamdani’s overarching goal of an affordable New York. In a state with thehighest income inequality in the nation, millions of workers urgently need the wage boost and job protections that only a union can provide. Moreover, it will take a huge increase in grassroots power to force Albany and Governor Kathy Hochul to fund Mamdani’s core policy planks for childcare, transport, and housing. Union resurgence could both feed into and feed off of a broader bottom-up movement for an affordable New York.

Moving in this direction will not be easy. Donald Trump has kneecapped the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), making it even harder than before for workers to act upon their federally guaranteed right to unionize. And most unions remain myopically focused on servicing their shrinking membership base. Despite a post-pandemic uptick in grassroots workplace organizing, unprecedented public support for unions, and the urgency of combating authoritarian Trumpism, most unions are still investing almost nothing into growth.

The good news is that city hall has a surprisingly high number of political and legal tools at its disposal, even though labor law in the United States is for the most part (but not exclusively) a federal purview. As mayor, Mamdani could leverage his platform as well as public policies to help turn New York back into a bastion of worker power — an affordable city with an organized working class strong enough to overcome the billionaires, Trump, and the Democratic establishment. What follows is an overview of some of the most powerful steps that Mamdani, should he win in November, could take to boost unionization in New York City.

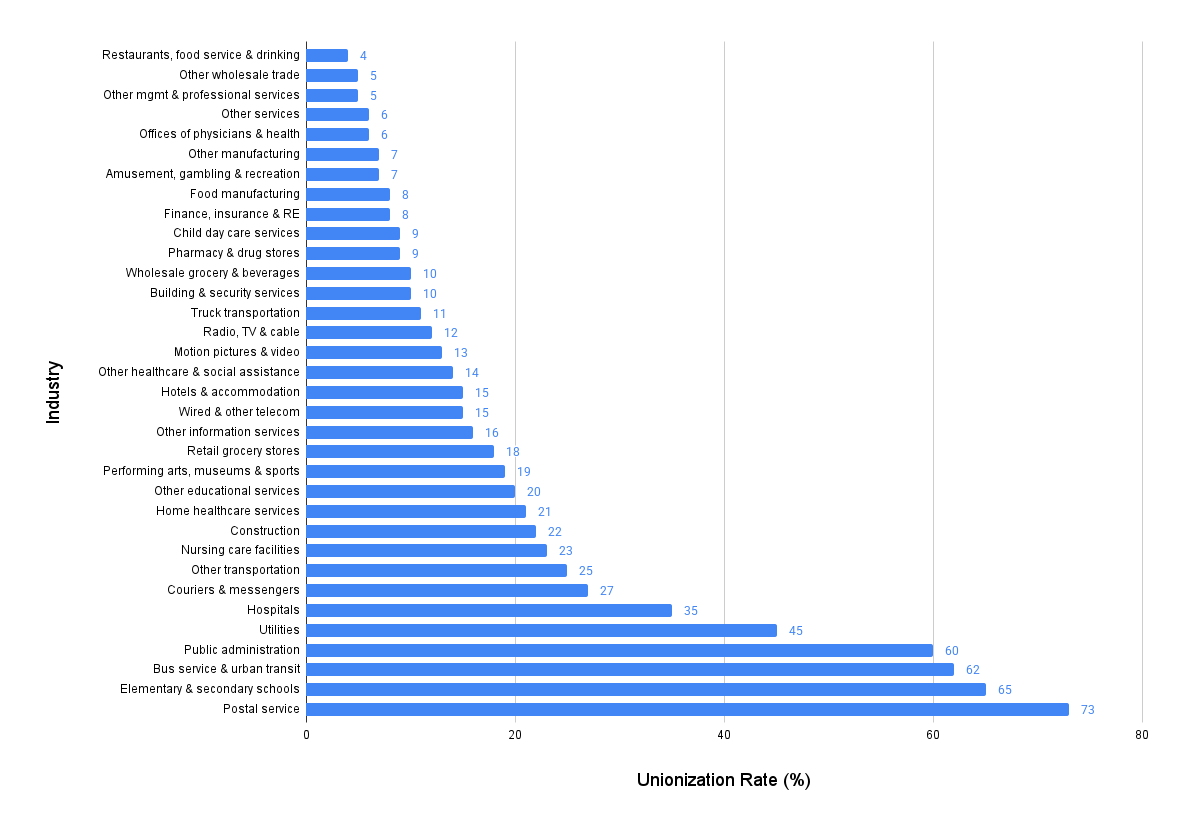

Figure 1: NYC Unionization Rate By Industry (2023–24)

Mamdani’s Bully Pulpit

By far the most impactful thing Mamdani could do to reverse labor’s decline requires no legislation, and it would cost the city virtually nothing. He just has to use his massive platform to encourage New Yorkers to unionize and to galvanize public support for organizing campaigns.

One of the biggest stumbling blocks to mass unionization is simply that most workers don’t realize that any job can become a union job if its employees start organizing. People assume that certain jobs are union and others are not — end of story. And even those individuals who realize that unionization is an option rarely act upon this insight since they don’t know how to begin unionizing, nor do they know where to turn for assistance.

Some of this began to change in the wake of the pandemic, as a growing number of left-leaning young workers — exactly the people who have rallied to Mamdani — fueled grassroots worker-to-worker campaigns at Starbucks, Amazon, and beyond. But the momentum of this surge has stalled after Trump’s election.

Mamdani could give this bottom-up movement a jump start. Here’s how David Kim, a New York City Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) labor activist, put it to me:

The main thing I hope a new [Mamdani] admin does, with its amazing communication reach, is to change the culture around unionization: to make it something not just good but cool. Workers are more likely to organize if they see the union as something that both meets this crazy historical moment and their immediate needs. People need to understand that they don’t have to wait for change from above or resign themselves to endless doomscrolling.

Mamdani could use his social media prowess to launch a public campaign to educate New Yorkers about why they should unionize, how to do so, and where to get organizing support. To grab people’s attention and raise their ambitions, it might make sense to frame and tie together these initiatives under a memorable four-year goal like “100,000 New Union Jobs” or another transformative-yet-doable objective.

The new mayor could host big online unionization trainings with the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee, as Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio Cortez have already done. If this led even a small fraction of Mamdani’s 50,000-plus volunteers and over six million social media followers to start organizing their own workplaces — or to take a strategic job to unionize it — this could potentially generate thousands of new unionization campaigns. And were Mamdani to act upon our proposal to launch a broad Movement for an Affordable New York (MANY), then the pool of new potential workplace organizers would grow significantly.

Mamdani’s bully pulpit would be of equal importance for helping workers get past the finish line and win a first contract, which is normally the hardest part of any unionization drive. Organizing efforts often live or die based on how much public support they get, and the mayor’s megaphone would go a long way to ensuring New Yorkers learn about pivotal labor struggles and hear how they can stand in solidarity. He could call out all acts of illegal union-busting. And in November and December of this year, Mamdani could play a big role in boosting Starbucks Workers United’s nationwide escalation to win a first contract. He could not only make viral videos about their struggle and show up at local actions but also call upon New Yorkers to take action in support.

The city itself could help educate the public about unionization and union campaigns. A Mamdani administration could direct city agencies to consistently inform constituents about their union rights, and it could make it easier for workplace organizing committees to book libraries and schools for meetings. Along the same lines, Mayor Mamdani would do well to adopt Brad Lander’s proposal to create an online know-your-rights hub for workers. Perhaps it would even be possible to add a 311 function for New Yorkers to call in requests for workplace organizing assistance. And to put pressure on companies to respect the unionization votes of their employees, New York City could publish online a list of companies where elections have taken place but first contracts have not yet been reached.

While it will also take an influx of union resources to organize effectively at scale, the crucial missing ingredient for mass unionization is a dramatic expansion of bottom-up worker initiative. Mamdani’s pro-labor bully pulpit can go a long way toward turning around the low unionization rates by industry seen in Figure 1.

No less importantly, leveraging Mamdani’s public platform is a crucial ingredient for making all of the following policy proposals relevant to the lives of millions of New Yorkers. When it comes to labor organizing, good technocratic fixes usually don’t amount to much if workers don’t know about these policies or how to act upon them. As one current city official put it to me, “The hardest thing is finding ways to inform workers about what their protections are. So a big part of the conversation has to be how we reach folks and explain things in a way they understand.”

Care Work, Nonprofits, and LPAs

Since employer retaliation and worker fear are central obstacles to growing the labor movement, one of city hall’s best and most underused instruments is to demand that employers who receive city money not interfere when their employees unionize. Such agreements in New York are known as “labor peace agreements” (LPAs) — though in our city, unlike many other places, the main LPA laws passed in 2021 neither ban strikes nor preclude their resulting collective bargaining agreements from explicitly including the right to strike.

Unfortunately few New Yorkers know about these 2021 laws (one of which was recently upheld by a federal judge), which enable any worker or union in contracted human services, or in food service in some economic development projects, to demand a labor peace agreement from their employers. Unlike much labor law at the federal level, this policy has teeth: if management fails to respect their workers’ desires to unionize, the city can cancel their contract and claw back subsidies.

A significant number of New York City workers are already covered by this law. After decades of farming out out what used to be public jobs — the city pays $23 billion in such contracts yearly — contracted human services alone employ about 80,000 people in occupations including “day care, foster care, home care, health or medical services, housing and shelter assistance, preventive services, youth services, the operation of senior centers, employment training and assistance, vocational and educational programs, legal services and recreation programs.”

This is a workforce, disproportionately nonwhite and female, that direly needs a union. The average income of New York City childcare workers, for example, was only $25,000 in 2023. Since it often pays better to work in fast food than to care for children, it’s no surprise that childcare centers statewide are mired in staff shortages and high turnover — problems that significantly lower the quality of care given.

Since childcare expansion is one of his core campaign planks, Mamdani has a great opportunity to make the case that improving these jobs via unionization is an important step toward better care for our kids — a proof of concept that can already be seen in the (still too modest) number of unionized childcare centers in the city. In forthcoming funding negotiations in Albany for childcare expansion, Mamdani could push to include pro-worker incentives — by, for example, adding subsidies for providers that have signed collective bargaining contracts.

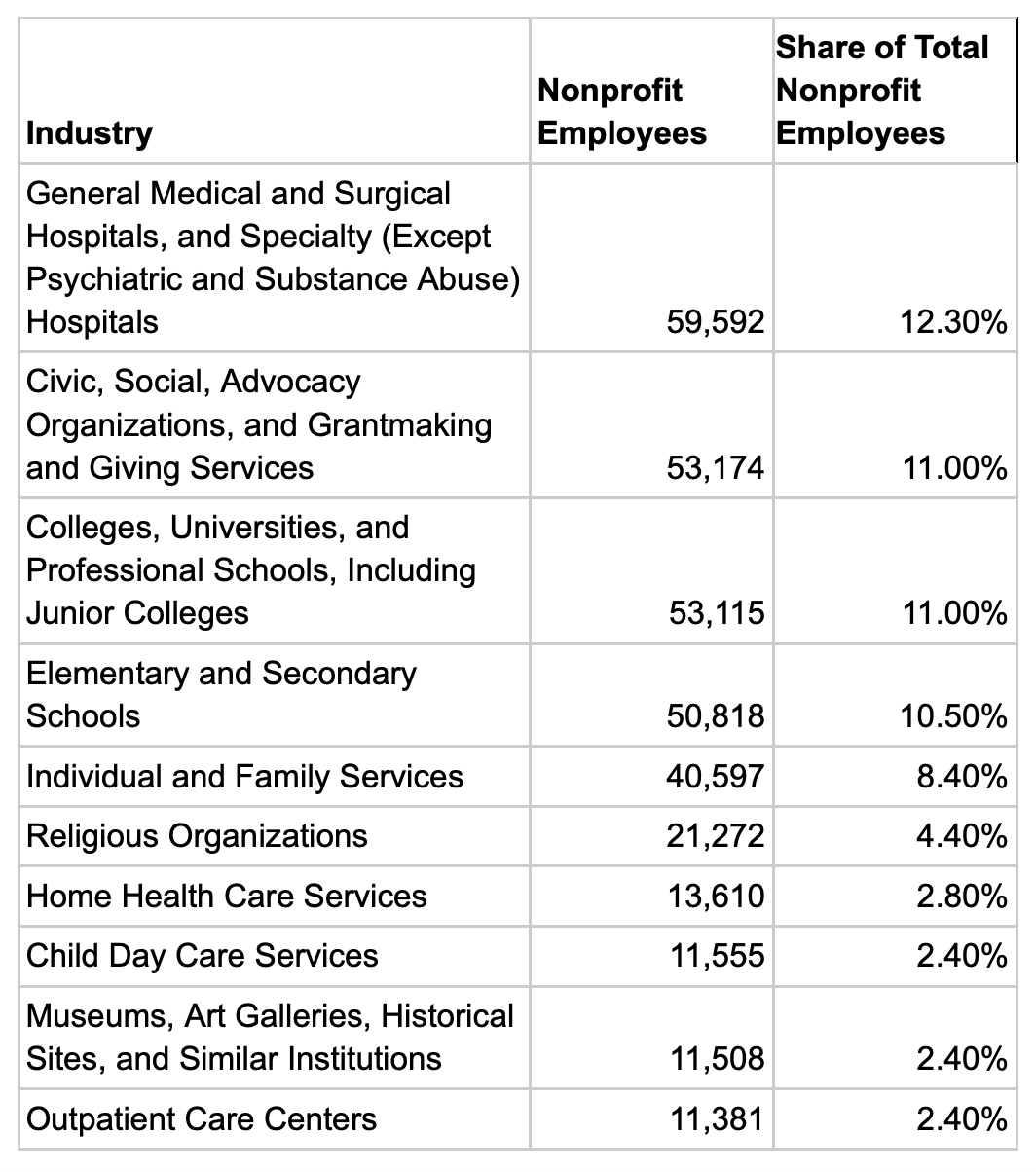

Table 1: Nonprofit Employment in New York City

Furthermore, in line with his campaign promise to expand labor peace agreement requirements, a Mamdani administration could strengthen the 2021 LPA law by more clearly defining neutrality requirements — for instance, by accepting a union when a majority of workers sign cards (“card check”) and providing employee contact information — and by strengthening its enforcement mechanisms. Through an executive order, Mamdani could also replicate this law to cover all workers who work in establishments that receive city funding. This is a potentially huge pool of workers, given that about 18 percent of workers in New York City are employed by nonprofits (see Table 1), many of which receive city funding.

Overall the nonprofit-industrial complex is ripe for unionization. Indeed, it has been a hub of recent union breakthroughs locally, from the New York State Nurses Association and the Service Employees International Union’s Committee of Interns and Residents victories at hospitals to United Auto Workers’ growth at cultural institutions like museums and nongovernmental organizations. These efforts can win many New Yorkers a living wage, and they can incentivize the city to stop outsourcing so much of its workforce — a wasteful process that needlessly throws taxpayer dollars toward bloated executive salaries as well as more direct forms of graft.

Scaling Up Union Construction and Affordable Housing

No industry in New York City has seen a more severe and rapid decline in union power than construction. As late as 1995, 80 percent of all major public and private construction work in the city was done by union labor; today the sector’s union density has plummeted to 22 percent. The results have been devastating for blue-collar New Yorkers: on-the-job fatalities at construction sites have risen, while pay and benefits have stagnated.

A Mamdani administration could play a significant role in helping make unions the norm again in the trades. For starters, it could easily tweak existing rules to ensure that project labor agreements (PLAs) — which require unionized labor — cover more city-backed projects. This could be done by setting up new local PLA requirements to fill gaps in the existing state statute and by consistently aggregating related construction projects to meet the current $3 million minimum threshold needed to trigger PLAs in New York City. (Per current state law, the PLA threshold in our city is double that of surrounding counties and six times that in the rest of the state.) More ambitiously, the city down the road could wage a battle in Albany to lower the $3 million PLA threshold, and it could consider passing a local law that ties PLA mandates to both construction upzoning and fast-tracking.

In the short term, as Mamdani has already pledged to do, the city can create at least 15,000 union jobs by retrofitting five hundred city schools into “green schools” with renewable energy infrastructure, interiors free of hazardous materials, upgraded HVAC systems, and bountiful green space. And eventually, the city could initiate other union-made infrastructure projects— for example, by decarbonizing all public buildings and building up municipal solar programs or building storm-surge and sea-level-rise protection.

Mamdani is also faced with the challenge of fulfilling his campaign promise to “triple the City’s production of publicly subsidized, permanently affordable, union-built, rent-stabilized homes, constructing 200,000 new units over the next 10 years.” This will be no easy task, since city-subsidized affordable housing currently relies almost entirely on a nonunion, low-wage workforce.

Unfortunately, today’s unionized contractors can’t effectively compete in bids for these projects, since affordable housing developers and the city don’t have the same financial cushion as big private developers to absorb prevailing wages in the trades. A rigorous independent 2016 analysis found that it would cost an additional $4.2 billion to pay prevailing wages to build the 80,000 new affordable housing units envisioned by then mayor Bill de Blasio.

To square this circle, the New York City Laborers’ Local 79 has spearheaded a coalition to get the city to pass the Construction Justice Act (CJA), which would mandate a reasonable wage and benefit floor as well as local hiring for affordable housing projects. Ensuring a minimum hourly wage of $40 would immediately lift a predominantly immigrant workforce out of poverty pay. And by leveling the bidding playing field between union and nonunion contractors, it could enable union labor to become the norm in the industry.

In conjunction with the expansion of city-backed apprenticeship programs, and the strict enforcement of diversification efforts in the trades, Mamdani’s support for the CJA would go a long way toward making possible his ambitious plans for union-built affordable housing.

Amazon and Gig Labor

One of the biggest obstacles to unionization and dignified working conditions is that many workers of the biggest corporations are not legally recognized as company employees. Amazon, for example, claims that its roughly 400,000 delivery workers nationwide are not employed by the corporation but solely by the third-party delivery service providers (DSPs) it subcontracts delivery to. Thus when DSP delivery workers in Palmdale, California, unionized with the Teamsters last year, Amazon responded by quickly terminating its contract with their DSP — essentially firing these workers for organizing.

Thankfully, the city has the legal power to establish a licensing regime similar to the Safe Hotels Act that would end subcontracting practices and thereby force Amazon to directly hire their “fissured” DSP drivers. A decision by Mayor Mamdani to take on Amazon by backing city council legislation to support DSP worker rights would be a boon for the ongoing unionization campaign of Teamsters Local 804. And by extending the Fair Workweek Law to warehouse and delivery workers, it would be possible to give another boost to union efforts by further stabilizing these workforces — and providing the city with further financial leverage against corporate behemoths.

Choosing sides in a David versus Goliath battle by low-wage black and brown drivers against Trump’s buddy Jeff Bezos is not just morally justified. At a moment of unprecedented support for unions and widespread revulsion at economic oligarchy, it’s also a politically smart move for Mamdani.

And though it would probably not be wise to pick big fights with more than one mega-corporation at the same time, Mamdani could also eventually push for similar legislation facilitating unionization among rideshare and gig workers at companies like Lyft and Uber. After the Federal Trade Commission’s January 2025 ruling that antitrust laws do not prevent gig workers and “independent contractors” from unionizing, the legal space for pursuing this route has opened up.

Hotels and Food Service

Hospitality is one of our city’s economic sectors with the lowest-hanging fruit for growing unions. During New York’s union heyday, over 90 percent of hotels were unionized, as were a majority of food servers citywide. Proof that organized labor’s decline cannot be attributed solely to deindustrialization, food-service union density has fallen to an abysmal 4 percent, and density in hotels and accommodation has dropped to 15 percent.

Fortunately the city has a considerable amount of leverage in this sector. Last year, it passed the Safe Hotels Act, which ends subcontracting for front desk and housekeeping workers — thereby making unionization easier — and mandates various pro-worker regulations. By baking in more tailored protocols for unionized establishments, the law also incentivizes owners to reach collective bargaining agreements with their workers, to avoid having their licenses revoked by the city’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP).

The DCWP could similarly leverage the 2017 Fair Workweek Law, which ensures regular scheduling in fast-food (and, to a lesser extent, retail) and the 2021 “Just Cause” law preventing unjust firings in fast food. Starbucks is currently in mediation with the DCWP over tens of millions for breaking these laws, a fact that the union and Mamdani could highlight and leverage in this fall’s big contract battle.

Moreover, to incentivize collective bargaining at Starbucks and beyond, “the city could tweak the rules of the Fair Workweek Law to dramatically lower fines for companies with union contracts,” explains Louis Cholden-Brown, a New York legal theorist and strategist who previously worked for the city for ten years and on many of the existing work laws. A similar provision on the books, for example, ensures that union car wash companies can pay one-fifth as much for mandatory bonds as their nonunion competitors.

Such a policy initiative could help win a big potential first contract victory at Starbucks later this year as well as pave the way for organizing in other coffee chains, in fast food, and in retail — a dynamic likely to get a major boost from an inspiring, precedent-setting contract win at Starbucks. To further encourage unionization in food service, the city could add a Unionization Status sign to the health inspection grade signs all establishments in the city have to display, and it could mandate LPA rules for all food-service establishments that use outdoor street space (since the city’s consent to use public space can require an exchange of contractual promises).

The Secure Jobs Act and Just Cause for Gig Workers

Just last week, twenty-one Rose Lane restaurant and bar workers were fired after they filed to unionize. Unfortunately this is an incredibly common occurrence. Research has found that employers break labor law in 41.5 percent of union drives, often through illegal terminations. And workers understand this, which is why far too many hesitate to stand up for their rights.

To protect employees against unjust firings — whether due to organizing or other issues like dealing with childcare emergencies — Mamdani can continue to throw his weight behind the Secure Jobs Act. Introduced in the city council by DSA Socialists in Office councilmember Tiffany Cabán, this bill would establish “just cause” job protections for all workers employed in New York City. Occupationally targeted bills are also currently being debated in city council to establish “just cause” protections for delivery app workers and for Lyft and Uber drivers.

Once workers understand that they cannot get fired for acting upon their legally mandated right to unionize, we can expect a significant uptick in grassroots organizing. And whereas federal labor law suffers from taking way too long to enforce — e.g., getting a fired worker back their job many years later — the city has already proven it can enforce workers’ rights more quickly. But the prerequisite for putting teeth on this law, as with the other policies listed above, is that the city give itself sufficient enforcement capacity.

Enforcing Workers’ Rights

“The private sector is not necessarily going to respect our laws just because we pass them,“ a city official told me. “So we really need to beef up our enforcement — and to pick some high-profile fights to scare the rest of employers into respecting the law.” This is particularly true at a moment when Trump’s administration has declared war on the administrative state. A Mamdani administration has the possibility and responsibility to fill in the vacuum as best as it can.

Building off his campaign pledge, Mamdani should commit to doubling the staffing of the DCWP, from roughly 450 employees to 1,000. Not only would this significantly grow the city’s ability to enforce workers’ rights, but in all likelihood, it would cost the city next to nothing, since the agency generally pays for itself through the fines and licenses it leverages from companies. In the last fiscal year, the DCWP brought in $21.5 million from its licensing and enforcement activities while only spending $17.5 million on staffing; and in fiscal year 2023, it raised $21.8 million while costing only $16.4 million. To celebrate May Day 2025, the agency announced it had wrested almost $4 million in fines and recoveries from Starbucks, Petco, Halal Guys, and a Pizza Hut franchise.

And given that dozens of city agencies beyond DCWP are potentially implicated in enforcing workers’ rights, Mamdani should consider adopting Brad Lander’s proposal to create a Mayor’s Office of Workers’ Rights to “lead a cross-agency strategy for protecting and promoting the rights of workers in New York City.”

Challenges and Dilemmas

While the mayor has real levers to boost union membership, it’s also important to address the significant challenges and dilemmas that will confront any attempt to move on this.

Competing Priorities:

Since administrative capacity, popular attention, and budgets are finite, the new administration will have to make hard choices about prioritization. There are only so many funding and policy fights that one can realistically pick at the same time. Especially given that Mamdani campaigned with a hyper-disciplined focus on passing three affordability policies — childcare expansion, free buses, and affordable housing — it is necessary and justified for his administration, and the popular movement backing it, to focus on passing this core agenda and maintaining Zohran’s overall popularity.

That said, there are strong reasons to believe that boosting unionization can be a key, if admittedly secondary, complement to this overarching focus. Some of these reasons have already been alluded to above: unions are very popular, they’re crucial for making the city affordable by boosting wages and by forcing Albany to fund Mamdani’s agenda, and they don’t cost the city anything in the private sector.

Since legislative battles can take a long time (and are far from guaranteed to succeed), it’s important from the outset for the new administration to come out swinging by proactively shaping the narrative and picking smart battles against bad bosses. Early pro-union executive orders combined with support for big unionization battles like at Starbucks can show New Yorkers that Mamdani is doing everything in his power to immediately fight for and alongside working people.

And while Trump and other establishment politicians will try to polarize public opinion in the city and nationwide around the issues they feel they’re strongest on, immigration and crime, sometimes going on the offensive is the best form of defense. Against these inevitable distractions and provocations, Mamdani-backed unionization battles can keep popular attention on the fight of ordinary working-class New Yorkers to win an affordable city.

Risk-Averse, Lethargic Unions:

The reason union density declines every year is not just that companies ruthlessly union bust with few legal consequences. It’s also true that in this daunting context (exacerbated by Trumpism), the vast majority of unions continue to invest little to nothing into new organizing, preferring instead to focus on servicing the members of their ever-shrinking islands of union density. For anyone doubting the risk aversion of New York labor, recall that most unions in the 2025 primary endorsed Andrew Cuomo.

Just passing good pro-union policies won’t be enough on its own to get organized labor as a whole to meet the moment. Indeed, most labor leaders exasperatingly stuck with business as usual after 2020 despite the incredible opening for growth created by the Biden administration’s excellent NLRB plus an exceptionally tight labor market.

As such, it makes sense to initially prioritize unionization policy fights in sectors with ambitious, fighting unions, some of whom I’ve highlighted above. But the post-pandemic growth of youth-led worker-to-worker unionism also shows that bottom-up unionization battles can go viral despite union officials’ inertia, and that such efforts can transform stagnant unions and pressure cautious officials to start investing more in growth.

So while it’s important for the Mamdani administration to work closely with union officials around contract fights and potential unionization campaigns, he shouldn’t hesitate to use his bully pulpit and policies to encourage organizing that does not wait for permission from lethargic institutions. Bringing fresh rank-and-file energy into organized labor, moreover, may prove to be pivotal for generating enough bottom-up pressure on union officials to not jump ship from Mamdani’s camp when the going gets tough.

Union Disunity and Narrow-Mindedness:

Unfortunately, the term “labor movement” is a bit of a misnomer today. Rather than a cohesive movement committed to fighting for worker solidarity and the interests of all working people, what we have instead is a huge number of siloed, frequently competing organizations focused primarily on narrowly fighting for what union officials believe to be in the best interests of their members.

Unions frequently come out on different sides of important policy fights, creating intractable dilemmas for any administration seeking to fight for the interests of the working class as a whole. For instance, various powerful unions opposed congestion pricing — a Metropolitan Transportation Authority policy supported by Mamdani. And it’s possible that not all unions in the construction trades will ultimately get on board with the specifics of Mamdani’s push to scale up affordable housing. A Mamdani administration will not be able to please all unions all the time and will have to be ready to periodically anger some union leaders.

City Leverage vs. Financial Cost:

When it comes to labor policies, another crucial dilemma is that city hall has the greatest leverage to support unionization in precisely the industries (city workers and contracted workers) that could end up costing the city the most financially. Conversely the low-wage private-sector workers who would benefit the most from unionization — and whose contract battles cost the city nothing — are those for whom city hall has less immediate leverage.

Mamdani will have to make hard choices about how to balance public workers’ demands with broader financial considerations. And he’ll have to find ways to balance support for public sector workers with ambitious-but-winnable policy fights in the private sector — even if these are more likely to confront legal challenges.

Preemption and Local Labor Law:

All of the policies listed above are legally sound, and most have clear prior precedents. Nevertheless, this does not preclude a cynical, billionaire-funded opposition from taking some of these policies to court, especially the more novel and ambitious initiatives to boost unionization in the private sector. While fights around the latter are necessary, it’s true that they could cost the city’s legal department some time and money — and if any go down to legal defeat, this might cost Zohran a limited amount of political capital. Rather than attempt to go full steam ahead on all these pro-union policies at the same time, a Mamdani administration should judiciously and strategically choose which battles to pick and when to do so.

This is especially true if the new administration chooses to test the waters in breaking new ground on implementing local labor law. As labor scholars like Cholden-Brown have argued, the National Labor Relations Act does not, contrary to popular belief, preclude cities and states from implementing labor law. Especially with the current lack of a quorum in the NLRB and with Trump’s push to end NLRB independence from his administration, further legal space has opened up for ambitious cities to create the equivalent of mini-NLRBs locally to set and enforce labor law widely across industries.

Though it wouldn’t make sense to immediately embark on such a big fight, Mamdani can keep this card in the administration’s back pocket. If unionization momentum really takes off, or if Trump’s authoritarianism and armed city invasions oblige an ambitious policy (and narrative) counteroffensive, New York City should keep all its options open. At this moment of unprecedented crisis in American democracy, what today seems impossible could suddenly become necessary down the road.

A New Path, in New York and Beyond

Making a concerted effort to boost unionization in New York City is a low-risk, high-reward wager. As long as Mamdani keeps his eye on the prize of winning his core policy planks, there’s not much cost to his administration if initiatives to reverse labor’s decline don’t ultimately pan out. But if they do succeed partially or fully — and they could — Mamdani will have helped galvanize a movement with unparalleled power to win an affordable New York.

Just as Mayor Fiorello La Guardia leaned on and boosted organized labor to lift New York City out of the Depression in the 1930s, Mamdani can do the same today to show the nation that there is a viable alternative to Trumpism. Pledging to make New York a “100 percent union city,” La Guardia argued that “if the right to live interferes with profits, profits must necessarily give way to that right.” By reviving that sentiment, Mamdani can chart a new path for New York City and our whole country.