As Neoliberalism Crumbles, It Becomes More Destructive

Economist Branko Milanovic is one of the sharpest critics of global inequality. He spoke to Jacobin about how the decline of neoliberal globalization is harshening its most destructive tendencies.

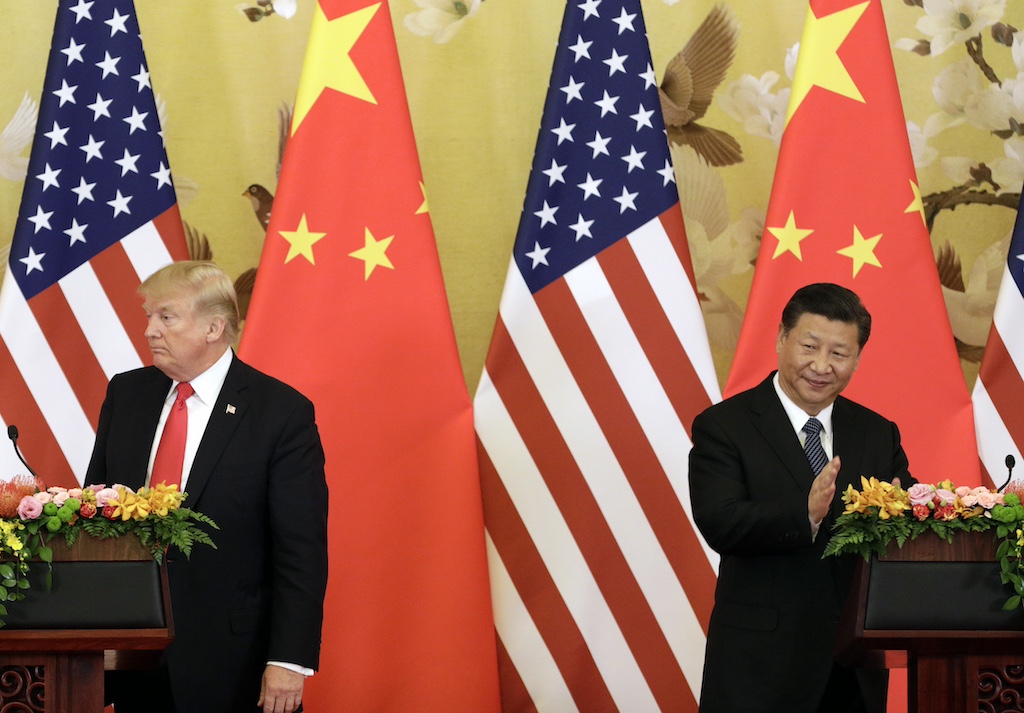

In the future, economist Branko Milanovic sees not so much an opening for the Left as a shoring up of capitalism’s most destructive tendencies.(Qilai Shen / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Bartolomeo Sala

Branko Milanovic is one of the most authoritative commentators on global inequality, globalization, and capitalism. He’s written about these topics extensively in his books Capitalism, Alone and Visions of Inequality as well as The World Under Capitalism, an anthology of his popular blogs on these subjects.

The so-called Elephant Curve — the famous graph looking at global income distribution, which he produced together with Christoph Lakner in 2013 — is perhaps the best encapsulation of globalization’s achievements, such as an overall reduction in global inequality, as well as underlying woes, such as the rise of an unaccountable global elite.

In an interview for Jacobin, Bartolomeo Sala asked Milanovic about his new book, The Great Global Transformation. They spoke about how the phenomena long observed by Milanovic have led to the crumbling of the US-led global neoliberal order, which ruled since 1989. Looking forward, Milanovic sees not so much an opening for the Left as a shoring up of capitalism’s most destructive tendencies.

Your title is a clear nod to Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation. His text famously opens with the sentence, “Nineteenth-century civilization has collapsed. This book is concerned with the political and economic origins of this event, as well as with the great transformation which it ushered in.”

Is it fair to say that The Great Global Transformation is trying to do with neoliberal globalization what Polanyi did with nineteenth-century market liberalism — that is, identifying its failure as the reason behind the rise of fascism?

Well, yes, there are similarities. Obviously, in the title, except that I add in the word “global” because the transformation that we are witnessing today is really entirely global.

However, the idea is pretty similar. As you said, the beginning of Polanyi’s book is essentially trying to understand what happened first with industrialization, and then why the new order collapsed already in the 1920s and 1930s. Likewise, this book takes the reader from the 1970s onward and looks at what I call the different challenges to Western domination. Then it asks the question: Why did things change? And what changed?

You identify the rise of Asia — specifically China — as the catalyst for this retreat of neoliberal globalization, an orthodoxy that had ruled basically unchallenged since the fall of the Eastern Bloc in 1989. I think you encapsulate this well when in the preface you write, “The rise of China that was made possible thanks to global neoliberalism made the end of global neoliberalism inevitable.”

From a purely economic standpoint, this rise should be seen as a positive — as it involves a rebalancing of the scales in terms of global incomes. But it’s also come with a few unintended consequences, such as geopolitical tension and right-wing populist backlash in the West.

Let’s suppose we are talking with a benevolent spectator. Coming from not knowing things, he would say, look, what happened over the last fifty years seems generally good. Global GDP went up three times. You had much greater equality of mean income between world citizens because of the rise of populous countries like China, India, Indonesia, Vietnam. On top of that, there was the creation of — I cannot call it a global middle class — but certainly a global median class.

If you look at these three developments, they all seem very favorable. However, when you start to break things down you see that the first problem of this equalization of incomes is that there is a big country like China which now has overtaken the United States in total GDP in terms of purchasing power. That creates geopolitical conflict because ultimately, the US doesn’t want to release its global hegemony, and it sees China as a challenger, certainly in Asia if not globally.

So, these good developments first create conflict at the level of nation-states. But then you can say to this observer, look at what happens domestically. Many people lost their jobs and got lower wages. Capitalists from rich countries outsourced things abroad. The middle classes in rich countries were unhappy with globalization and decided to vote for populist candidates.

This is the theme of the book. How is it that something which at the global level can be considered a good development — and I have discussed its three aspects — proves to be a problem both at the level of geopolitics but also at the national political level? I must add that this is not at all surprising, because the rise of Asia is such a big change that no one could expect that it would be absorbed painlessly.

Together with the rise of Asia, you identify the formation of a new ruling class or elite as the other great development coming out of forty years of neoliberal globalization — or “globalization II,” as you call it in a recent Jacobin essay, which covers much of the same topics as the book.

This class, which emerges from the (sometimes literal) marriage of managers and capitalists, or capitalists and party cadres, now rules both in China and the US. I think it’s a really interesting observation in that it belies the Samuel Huntington–type narratives that identify the two countries as two incommensurable models or civilizations. Moreover, you also identify Donald Trump, Xi Jinping, and Vladimir Putin as expressions of a common reaction against their rise. How are these new elites, rich in capital, credentials, and labor income — which you call “homoploutic” elites — different from the past?

It’s a great question. I think the first account I gave about the rise of China and Asia was a bit simplified. It was really two developments, and they were both part of the same neoliberal package.

Internationally, there was the development of China and domestically the creation of an elite, which is rich both in terms of capital and labor, that left others in between, so to speak. Consequently, the rise particularly of Trump — because I think he is really a paradigmatic case — is explained by these two movements, together with the self-perception of those who did very well, had high credentials, and actually perceive themselves as very hardworking.

I use a lot of Daniel Markovits’s The Meritocracy Trap when I discuss that. As Markovits says, and I quote him, the Stakhanovites of today are really capitalists because, in the financial sector for instance, they often work ten to twelve hours a day. They feel they deserve things. And they also feel those who have not done well are guilty for that. It is actually their fault because they have been either not smart, didn’t study enough, or couldn’t find the opportunities. So, there’s this contempt for other citizens as well.

I’m very happy about my third chapter, which you allude to, because it presents both the American and Chinese elites empirically. The American elite is a “homoploutic” elite with all the characteristics I mentioned — they are the richest capitalists and richest workers, which is a historical novelty, but they also harbor an almost Calvinist pride in their success and contempt for the next person. On the other hand, with the Chinese elites — who also became much richer — you see the importance of Communist Party membership. This, of course, makes total sense, because if you are a rich capitalist, you need good connections and influence with your government.

For the American elite, credentialism is basically going to the universities that would actually then give you a good job. For the Chinese elite, credentialism is party membership, because this is something which ensures your business will be safe.

Talking from a purely Western standpoint, wouldn’t it be more accurate to identify this new ruling class, which likes to portray itself as a meritocracy but really is a new oligarchy, as the root cause of the populist backlash — rather than scapegoat China? After all, offshoring is not China’s (or India’s or Brazil’s) fault. Nor is it their fault if Western leaders — and here, I am thinking of extreme centrists like Emmanuel Macron or Keir Starmer — myopically insist on the same bankrupt neoliberal policies rather than redistribute some of the wealth that globalization distributed so unequally.

I totally agree. I think it is the coincidence of the two. China, of course, played a role. But at the domestic level, it was also the elites’ stubbornness in not recognizing that they were losing people’s support. They were too busy with their success and blinded by belief that their success was deserved. I mention this in my recent blog post “Defeated by Reality.” I have many friends who are baby boomers who are now retiring and they are huge believers in that. They believe they deserve things and others do not because they did not go to the right schools. They would actually say: of course, there was a difference if you have rich or poor parents, but anyone could do it. I think both the rise of China and the rise of this neoliberal elite led to the creation of a mass of dissatisfied people who then voted against them.

In the ruins of the old neoliberal order, you see the coming of a new global system. Here, unipolarity and the US’s undisputed post–Cold War hegemony is replaced by multipolarity, and neoliberalism ushers in what you term as “national market liberalism.” This is really the crux of the book, the “great global transformation,” which you refer to in the title. Is it fair to say that we are not witnessing a paradigm shift but rather a mutation by which liberalism gives way to aggressive mercantilism abroad, while neoliberalism continues to rule at home?

Absolutely. That’s why the book’s subtitle is “National Market Liberalism in a Multipolar World.”

We all agree that neoliberal globalization has really run its course. It’s not only because of Trump. Joe Biden’s policies as president were very similar. Then the question becomes what type of system comes next, because we all agree that neoliberalism, as it existed from the 1990s until 2016, at least, has now changed. I don’t need to go into detail about trade wars, big economic sanctions, or tariffs to talk about that. But what you notice for Trump very clearly — and I think there are similarities elsewhere — is that relations with other countries have gone into clear mercantilistic mode.

What is liberalism, or even neoliberalism? In the book’s fourth chapter, I present four quadrants. Domestically, it means free competition, low taxation, low regulation, and so on. Socially, it champions negative freedoms, affirmative action, acceptance of sexual and racial differences. On the international level, it has also got two parts. Economically speaking, it is about free trade, while socially speaking, it strives for cosmopolitanism, which, in a pure state, would actually involve freedom of movement of labor and people.

So, you take a look at these four quadrants. Very simply the international part is all gone. Trump simply says: no, that doesn’t apply anymore. As to the domestic part, the negative freedoms and acceptance of different kinds of people and groups is also under attack. So, what remains is really only one quadrant, which is market liberalism. And in this respect, we see that Trump is not only pursuing, but deepening neoliberal policies. Reduction of taxation, lower regulation on practically anything, lower tax on capital than labor — he is doubling down on all of these things.

What do you call this new system? We call it “national” because it applies only nationally and we call it “market” because the social part doesn’t really apply anymore. Hence the term “national market liberalism.”

You base your analysis in long-term, observable trends. Yet to me, this new arrangement or world order you are describing seems especially brittle, fragile, and potentially explosive.

It is not just that in a world of rival powers capital still needs to expand (hence the constant geopolitical tensions and warmongering). Perhaps with the exception of Xi’s China, it seems determined to exacerbate the social crises which neoliberal globalization created.

It goes back to Polanyi’s idea of “double movement.” The losers of globalization have nothing to gain from this retreat of neoliberalism within national borders; if anything, they will lose further as the welfare state is slashed in the name of rearmament and social safety nets are privatized and replaced by even more inequality. Don’t you think it’s just a matter of time until society strikes back?

If I look at Trump’s policies, I tend to expect that inequality in the US would go up because these are policies that are historically connected with increased inequality.

At the same time, Trump is a demagogue. Technically, he cannot run for a third term, but even so I don’t think the movement he started is going to go away. Likewise, in Europe, in France, which is now going through a government crisis, you would probably have a Rassemblement National candidate in power if Macron were to resign. It’s the same in Britain, with Reform UK. In Germany, you have the rise of the Alternative für Deutschland.

So, these are not accidents as such. I am skeptical about what they would be able to achieve. But even so, I think that there is an element of dislike for the elites, by which people who are unhappy with the state of things would accept anything so long as the elites are not in power, even if they themselves don’t do very well.

One notable omission in the book is the role of climate change. For all its clear-eyed analysis, it almost assumes that the world will carry on business-as-usual when it comes to climate. However, we know this to be far from the truth. What do you think of this? Will climate be just another stressor in a world already in a state of worsening polycrisis?

This is not going to be a popular answer, but I don’t think climate change is a danger of the same size and importance as these other factors that I have discussed.

I believe in climate change and believe there will be effects. There will be parts of the world that will become unbearable, but there are other parts of the world, especially Russia and Canada, that would benefit from that. Secondly, I believe we will have technological solutions.

I am old enough to remember this claim that we are a limited planet and there is no unlimited growth on a limited planet.

We might be a limited planet, but our use of resources is technologically determined. I don’t agree with the view that there is a barrier, and once we hit that barrier, capitalism would collapse. Even so, what system would replace it? I could understand a reduction in the rate of growth because green technologies require more technological development for lower yields.

I am pretty much a Marxist methodologically, and don’t believe capitalism to be a natural mode of production, which leaves open the possibility of it being transcended or replaced by a better system. However, I don’t have a blueprint for another one.

You’re a realist who doesn’t see any alternatives to capitalism surfacing on the horizon anytime soon. This doesn’t mean, though, that you are not deeply critical of capitalism. Indeed, the conclusion of The Great Global Transformation is a real indictment of capitalism’s voracious character. Is it right to say that — even if you don’t say it explicitly — you see war as the more likely outcome of this historical conjuncture? Are we sleepwalking into another tragedy?

I’m not too sure about the war. I mean, you know the situation currently. It could happen even now.

But what I say in the last chapter — which is only a few pages long, but I also argue this in Capitalism, Alone — is that capitalism is essentially an immoral system. A system driven by self-interest and profits. This whole story about stakeholders and shareholders, I think, is basically nonsense. I actually agree with Milton Friedman, here. The business of a capitalist as a social agent is not to care about the environment and other people, but to care about shareholders and his money. It is a system that, as I said, is amoral and commercializes everything.

That’s another point that I make in the book. We have activities that never have been commercialized. The entire domestic sphere of activity has probably been commercialized. Cooking has probably been commercialized. Taking care of dogs has been commercialized. Taking care of the elderly has been commercialized. Even dying has been. The quasi-disappearance of family is probably the ultimate consequence of this, in that family is defined by activities which in principle are not commercial.

So, when you commercialize everything, it’s not surprising that what you have is a world of loneliness. The only quote I have in that chapter is from Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle. The book was written in 1968, a phenomenal book. It’s uncanny how he saw that coming. In that sense, I am very pessimistic. It’s a stern pessimism, but in an increasingly atomized society, that’s where I think we are headed.