The US and China Are More Alike Than They Think

In the US, lawyers gridlock politics, and in China, engineers solely concerned with development steamroll individual liberties. A new book argues that both nations could learn from one another, but their rivalry is obscuring the social crises they share.

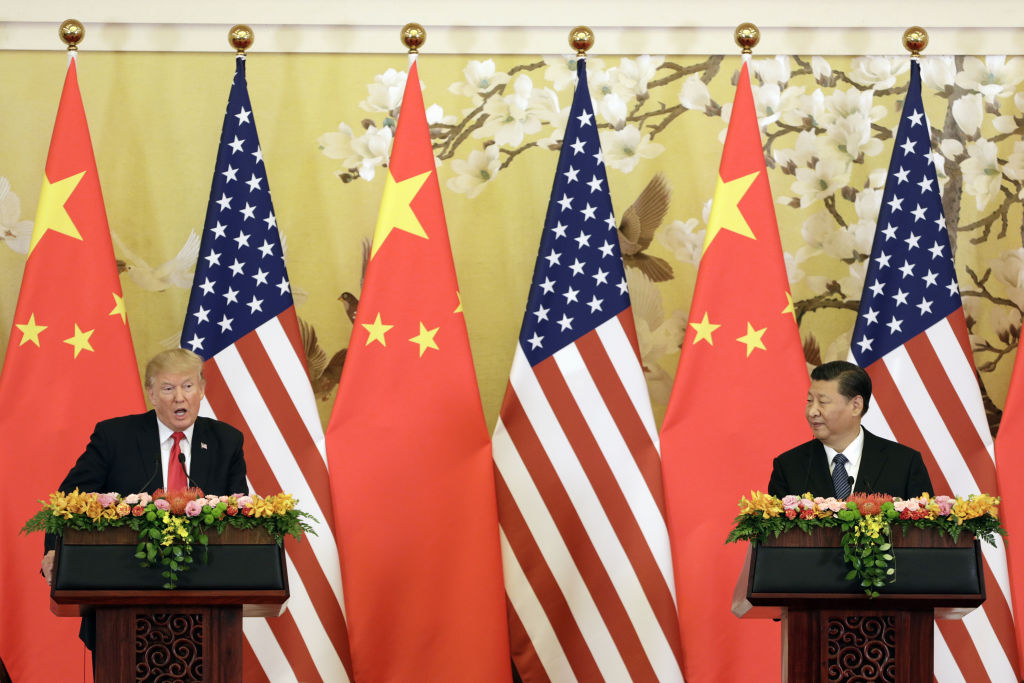

Donald Trump and Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, on November 9, 2017. (Qilai Shen / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Something about the United States is broken. Our already mediocre infrastructure is crumbling, the pace of housing construction is glacial, and we’re one of the few advanced countries without high-speed rail. Although Bidenomics — the set of economic policies aiming to both address inequality and reindustrialize America’s economy — made progress, its deficiencies also revealed deep dysfunction. The Biden administration fell flat on its face at the relatively simple tasks of expanding internet access and installing more electric vehicle charging stations. Meanwhile, Republican states employed lawfare in a cynical attempt to stop the green transition that the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) tried to kick into gear.

For the last few decades, China has been on the exact opposite trajectory to the United States. The People’s Republic puts up highways, bridges, and trains at a whirlwind pace. It is now the global leader in manufacturing, and there are few products that it can’t create. It’s moved up the value chain from making T-shirts and toys to high-tech products like electric vehicles (EVs) and solar panels. China’s stupendous installations of solar, wind, and nuclear power makes the IRA look pathetic in comparison. In short, China’s historic productivity has been the complete inverse of America’s malaise.

Dan Wang’s new book, Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, sets out to offer a new framework for explaining this disparity. For Wang, China is an “engineering state” while the United States is a “lawyerly society.” The engineering state “builds big at breakneck speeds,” putting up railways, bridges, and factories at a speed that no other country can match. In contrast, America’s lawyerly society is all about obstructing construction and creating dizzyingly obtuse procedures that thwart all change, both good and bad. In addition, the lawyerly society tends to be best at serving the rich, who are best equipped to navigate the labyrinth of legalistic confusion.

Breakneck is mostly devoted to talking about one side of this dichotomy. Chapter one feels like the beginning of a comparative political economy of the Chinese engineering state and the American lawyerly society, but the book proceeds with an intense focus on the former. From chapter two onward, the lawyerly society retreats into the background with just a few scant references, only returning into focus again in the conclusion. Breakneck is a fantastic book about China, but it really is a book about China. Readers shouldn’t expect a deep dive into the workings of America’s lawyerly society.

The Engineering State

China’s engineering state has made it the manufacturing center of the world. It is now the world’s number one manufacturer, making up 29 percent of global total manufacturing value added as of 2023 — compared with 16 and 17 percent for the United States. This has been accomplished not only by expanding output of low-value goods like clothes and toys but also a robust state-led effort to dominate production of high-tech goods. “Made in China” used to be a signifier of shoddy quality, but it now represents advanced production of some of the most complex products on the market. The engineering state’s Made in China 2025 initiative has transformed the People’s Republic into a global leader in high-tech industrial manufacturing.

This manufacturing success has made China the envy of the world; anyone serious about understanding how a green transition could be must look to China, which dominates in technologies such as EVs, solar panels, and wind power. China makes up 70 percent of global production in EVs and controls 80 percent of the solar panel supply chain. These renewable technologies have also been adopted at a rapid pace. Domestic EV sales have risen 38 percent in 2024 alongside record-breaking growth in solar and wind installation.

Green growth is largely the result of state-directed industrial policy. Massive government subsidies, tax incentives, and bank financing designed to hothouse investment into green technology have turbocharged the sector. While inequality has increased during this period, the Chinese engineering state’s policies have accomplished some of the most ambitious goals of the Green New Deal. Almost every part of this program remains a dream for the United States.

Beyond green tech, China has been able to build, build, and build housing and infrastructure at a shocking rate. China’s rapid urbanization since 1978 has meant that it’s effectively built a city with double the population of New York City every year for the last thirty-five years. China’s high-speed rail network is longer than the rest of the world’s put together. In just twenty-seven years, it has built a highway system twice the length of the US interstate system. Fifty-one of China’s cities have subway systems, with eleven of them longer than New York City’s.

If there’s a reason that China’s government has been able to maintain legitimacy despite its authoritarianism, it’s because the engineering state can deliver the goods.

Engineering the People

The state’s ability to engineer has come with downsides. Industrial overcapacity, massive debts, and a property bubble pose serious problems. Despite this, engineering has, all things considered, been a huge boon for China.

The problem is that the engineering state can’t stop at just building. China’s government extends its engineering logic beyond roads and bridges and unleashes social engineering onto its population. Beijing tries to mold China’s citizenry the same way it does concrete and steel, treating people as aggregates rather than individuals. Behind the engineering state is an obsessive desire for control and a deep suspicion of the population. For Wang, this social engineering is the most objectionable aspect of the Chinese engineering state.

The horrors of Beijing’s social engineering hit hardest in the chapter on the One-Child Policy. The One-Child Policy was not the brainchild of a demographer or sociologist but a missile scientist. Song Jian believed that he could predict the trajectory of China’s population just as one could predict the trajectory of a missile. Like much of the world, the Communist Party of China (CPC) accepted the dominant view in the second half of the last century that overpopulation was an impending crisis.

Jian gave little thought to the possibility that fertility rates would drop as economic growth accelerated, or that growth would make overpopulation a nonissue. With its narrow, linear prediction of China’s demographic future, the social-engineering state launched the One-Child Policy, a historically unprecedented mass campaign of sterilization and abortion. In 1983 alone, the government sterilized sixteen million women and carried out fourteen million abortions, executed by a shock troop army of party cadres, local enforcers, and medical teams.

According to the Chinese government’s own official figures, there were nearly as many abortions as the current US population during the One-Child Policy’s thirty-six-year implementation. When women could no longer hide their pregnancies, local officials would force brutal third trimester abortions. In some cases, they engaged in outright infanticide, smothering babies the moment they exited the womb. The destructiveness of the One-Child Policy makes clear one of the many areas in which America’s lawyerly society excels.

Despite similar concerns about overpopulation being commonplace at the time, something like the One-Child Policy was unimaginable in the United States. The courts or civil liberties organizations would intervene if similar legislation or executive action was attempted and the American electorate would stage a revolt in the face of such an extreme violation of individual rights. For all of its pathologies, the United States’ obsession with personal freedoms and the lawyerly society’s ability to delay and obstruct can play a positive role in stopping bad ideas.

As Wang says in his book announcement, a good book on China needs to thread the needle between demonizing and glorifying its government, between focusing on hyper-specific narrow questions and making sweeping judgments. This is something I wholeheartedly agree with and, by this standard, Breakneck is a great book. The “engineering state” is such a useful concept because it simultaneously captures both the admirable and the abominable in China — the marvelous growth that’s pulled hundreds of millions out of poverty and the invasive authoritarianism that forces abortions and locks up labor organizers. Breakneck is the rare book that can ask the big questions about the massive, diverse country that is China without devolving into one-sided banalities.

Who Will Build the Ark?

Wang describes himself as “a sunny optimist for the future, with faith that both societies can change for the better.” For him, China and the United States are deeply complementary societies and should learn from each other. China needs a dose of lawyerliness to hold back the excesses of the engineering state, and the United States requires an engineering ethos to create new infrastructure, more housing construction, and a green transition.

But Wang’s own analysis makes it difficult to feel optimism about the future in either country. Lawyerliness is nowhere on China’s horizon. As China’s economic and geopolitical problems continue to deepen, Wang thinks that the engineering state will double down with more engineering solutions that are worse than the problems they aim to address. Wang suggests that change might come through “ordinary acts of resistance” such as noncompliance with government rules or young, disillusioned Chinese continuing to run to other countries. However, it’s implausible that serious change could come about without sustained, organized political pressure on the CPC — something that is nowhere to be seen. When I visited China recently, the pessimism was palpable, and there isn’t much in Breakneck to suggest that this sentiment was misplaced.

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book Abundance, which stirred fierce debate on the Left but has already gone on to influence policymakers in the United States from Zohran Mamdani to Gavin Newsom, provides the intellectual backdrop for much of Breakneck. Wang considers himself a card-carrying member of the abundance movement and is a listed speaker at the upcoming Abundance 2025 conference. When I asked him what Western socialists should learn from China, his immediate response was that it provides a good (but not great) operating model of abundance. In fact, Abundance reads like a supplementary critique of legal obstructionism, which Klein and Thompson argue has stood in the way of creating abundance in the United States.

However, when combining abundance’s politics and Wang’s view of the lawyerly society, a contradiction quickly comes into view. Abundance was intended as a manifesto for a vanguard hoping to rejuvenate the Democratic Party by moving beyond zero-sum conflicts between sections of society. But even by Wang’s own admission, Democrats are much more lawyerly than Republicans. Even when we’ve seen some Democratic engineering gusto through Bidenomics, it was, Wang writes, “industrial policy run by lawyers.”

This creates a serious obstacle to realizing some of the more ambitious aims of the abundance movement. The institution that is supposed to rein in lawyerliness is also the most legalistic of American institutions — nothing proves this more than the Democrats’ consistent faith that the courts, rather than mass democratic opposition, can bring Donald Trump to a halt. If we really want an abundant future of more housing, public infrastructure, and clean energy, Wang’s own assessment implies that we have to look for an agent beyond the Democratic Party to carry it out.

In the United States, commentators like Adam Tooze have enthused about the impressive successes of the engineering state to liberal and left-wing audiences. These interventions have helped to combat an increasingly hostile environment in which demonizing China has provided cover for elites unable or unwilling to implement comparable policies at home. What has been lost in well-meaning discussions of China’s incredible achievements has been a focus on its deficiencies.

China’s population holds many of the same grievances against its elites that are frequently voiced by the American left. The tax system of the People’s Republic is notoriously regressive and heavily dependent on consumption taxes, which disproportionately puts fiscal burdens on the poor. Pension and health care spending are dreadfully low and access to unemployment insurance is extremely restrictive. Xi Jinping’s frequent lectures about the dangers of “welfarism” could easily be direct quotes from Ronald Reagan.

In the past, these distributional issues could be papered over by China’s absurdly rapid growth. But as the growth model slows down, the country’s youth feel left in the lurch in the same way that America’s does. The phrases “lying flat” and “let it rot” have gained currency as young people feel like they have no economic prospects. Wang discusses this most directly in the phenomenon that Chinese people have taken to calling rùn.

In Chinese, rùn (润) literally means “to moisten,” but during the height of China’s zero-COVID policy, it became a meme for young people wanting to flee the country for better futures abroad thanks to its phonetic similarity to “run.” This is not unlike the experience that many Americans felt during COVID as they used the lockdown to reflect on the exhausting pace of capitalism and to ask whether the trade-offs they had made for their careers were worth it.

As US-China tensions continue to ratchet upward, we should remember that behind these two clashing governments are two peoples experiencing the same ills of a pessimistic economic future, a woefully insufficient welfare state, and a government that doesn’t care about their suffering. Maybe one day, that shared experience could be the basis of the international solidarity that we so desperately need in these dangerous times.