Socialists Must Aim for More Than Redistribution

Beyond the basic project of redistribution lies a more ambitious undertaking: What if we could collectively decide what society produces, instead of letting market logic dictate our needs and desires?

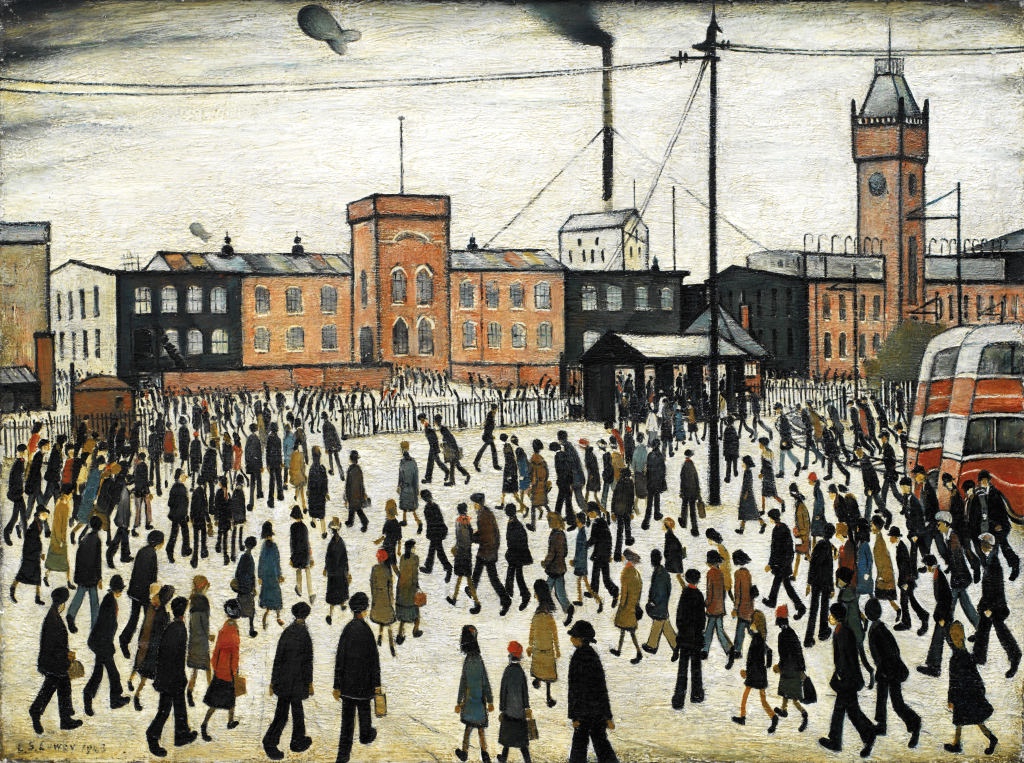

The difference between economic arrangements relies on the “ways of life” they create — that is, on the level of collective control society has over the definition of social aims. (Laurence Stephen Lowry / Imperial War Museums via Getty Images)

In April 1947, the architect Percival Goodman and his brother, the social critic Paul Goodman, published what would become a classic in urban planning: Communitas: Means of Livelihood and Ways of Life. Exploring the form cities have taken and how they have been envisioned over the centuries, they argued that far more is at stake in urbanism than technical functionality.

Cities always express the moral and cultural values of their inhabitants. How “men work and make things,” they added, is crucial to determining “how they live.” The aim of Communitas was therefore to try to imagine the city from the standpoint of the “relation between the means of livelihood and the ways of life.” To explore such a relationship, the Goodman brothers imagined different community paradigms that each took “value-choices” as “alternative programs and plans,” or different ways to define human needs and social purpose.

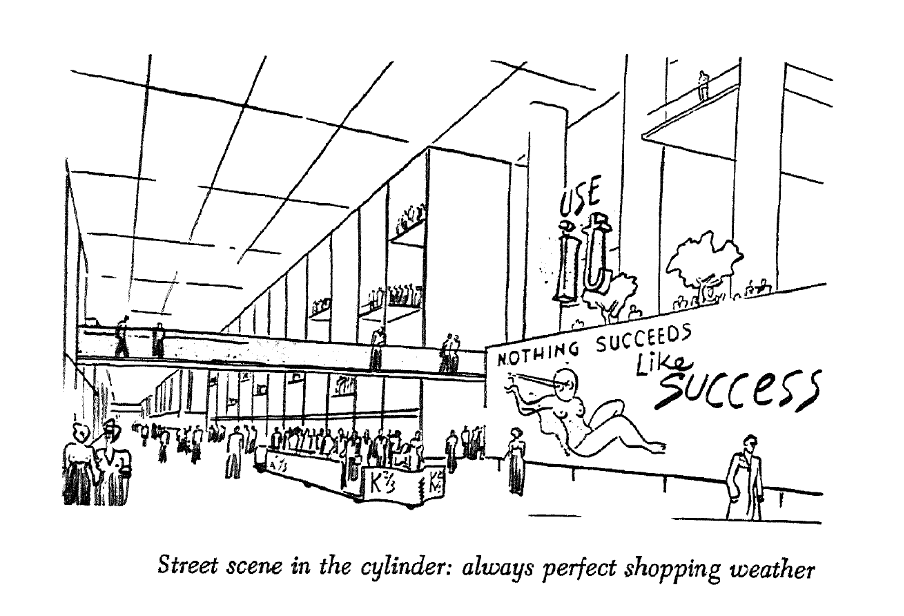

The first of these paradigms was a city organized around “the premises of the official economics” — a “metropolis as a department store” where everything is organized “according to the acts of buying and using up.” In such a model, the center of the city and of social life is a giant air-conditioned mall. Inside, a “permanent fair” is ongoing and, in every corridor, all the products “that make it worthwhile to get up in the morning to go to work” are on display. All around the commercial center, hotels and restaurants form a ring where customers can eat and rest.

In such a society, everything is in the service of the circulation of commodities. As the authors noted, “Poetry and painting are advantageous to sales; the songs of musicians are bound inextricably to soaps and wines.” Even the most intimate human feelings like “mother love,” “brotherhood,” and “sexual desire . . . make it imperative to buy something.” The authors concluded, “In this manner, the integral man is involved in the economy.”

Naturally, as the purpose of all social life is consumption, work becomes only a means to an end. This implies, the authors noted, that if “the tendency of production is toward quantity and sale on a profitable market, the possibility of satisfaction in the work vanishes.” The worker himself, uninterested in his activity as a producer, only wants to “hasten away wealthy” — to rush off as fast as he can “to the home, the market, the city, where are all good things.”

Under such a system, even politics becomes devoid of any meaningful content. Elections, they added, “are like other sales campaigns, to choose one or another brand name of a basically identical commodity.” In fact, focused on consumption, “people do not want to take the trouble to decide political issues because, presumably, they have more important things on their minds.” The real power they have is “the economic choice to buy or not to buy a product” — not the “strenuous efforts as boycotts or strikes, but of the delicate pressures of the market.” In other words, the consumer replaces the citizen.

As an alternative model, the Goodman brothers offered another metropolis where the dominance of consumption over production would be overcome, with a clearer integration of work within the city itself — a model where “every part of life has value in itself as both means and end.” In such a city, it is as workers, rather than consumers, that citizenship is exercised. If in a market-driven society workers are not acquainted with the whole order of production, in this new metropolis, they would have “a total grasp of all the operations.” This shift would radically transform the meaning of work and democracy itself. People wouldn’t desire “to get away from their work to a leisure that amounts to very little” as “people will be leisurely about their work.”

In this second model, the hub of social life is not a commercial center but public squares where people gather and discuss, as in ancient Greece. “Such squares,” the Goodman brothers argued, “are the definition of a city.” They are not “avenues of motor or pedestrian traffic” but are “places where people remain.” The piazza is everywhere — in front of a factory, at the entrance of a small library, or in front of an apartment complex where people meet and start conversations. This is a metropolis where “work, love and knowledge” are finally integrated, a city where the aim is “social security and human liberty.”

The Rules of Engagement

These two models illustrate quite strikingly the different ways a society can organize the relationship between the economy and democracy. In the first, democracy is displaced in the marketplace, replacing politics with consumption choices, while in the second, political deliberation guides economic decisions. The originality of the argument lies therefore in the fact that the contrast is not strictly on property relations (capitalism vs. socialism in a narrow sense) but on the different modalities in which a society can develop human needs. While in the first model they are delegated to the impersonal logic of the price system, in the second model they are the object of collective deliberation. What differentiates the second model is that it turns needs (what do we want to produce?) into a political and democratic issue.

This maps well onto the distinction between a “purposive” and an “unintended” social formation, to take a cue from the Austrian economist Friedrich von Hayek, meaning the difference between a society shaped by an impersonal mechanism (the market) and one where worth is decided by collective decision-making. As noted by the philosopher Brian Barry, “Choosing an economic system is not merely choosing a machine for satisfying wants but rather choosing a machine for producing certain wants in the future. It is therefore inevitably a choice to be made partly on ideal grounds.” What the cities imagined by the Goodmans impress upon is that the difference between economic arrangements relies, above all, on the “ways of life” they create — that is, on the level of collective control society has over the definition of social aims.

In a society where the price system is the central mechanism for allocating investment — the “department store society” — decisions over what should be produced are delegated to private actors using profit as a compass. In the real-world history of capitalism, this, if we follow the historian Ellen Meiksins Wood, meant the development of a historically unprecedented “sphere of power devoted completely to private rather than social purposes.” She added, “The social functions of production and distribution, surplus-extraction and appropriation, and the allocation of social labour are, so to speak, privatised, and they are achieved by non-authoritative, non-political means.” Here it is not the use value that defines what is made but its exchange value, making prices the sole unit through which the market mechanism selects what is worth producing.

By subordinating production to private ends, a market-driven society, to quote the philosopher Agnes Heller, “satisfies social needs only insofar as they are transformable (under the given conditions of market sale of labor power) into effective private demand on the commodities market.” Heller continues:

The typical consequence of the mechanism of capitalist production is that there is an increase in needs within a group of needs of a determined type, and an orientation of the individual towards their satisfaction — while other types of need, which shape the human personality, which do not help the valorisation of capital and can even hinder it, wither or fail to develop to the same extent.

Through this process, the conflict between different needs tends to favor those generating profit. For example, the limitless expansion of consumer goods becomes a brake upon the expansion of free time. People are unlikely to individually choose to work less if it comes at the cost of restraining the satisfaction of their needs relative to the rest of society. As long as new needs are produced, to catch up with the general level of consumption, reducing working time is unlikely to happen endogenously, even if individual workers might be overwhelmingly in favor of the idea.

The historical specificity of such a pattern of needs lies, therefore, in the fact that it evades society’s ability to define what’s worth. Put differently, in the market society, the ever-growing production of needs dominates social life while escaping any kind of democratic control. As the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins once observed, what the market society does, unlike any other society in human history, is “produce not only objects for appropriate subjects, but subjects for appropriate objects.” The “way of life” is one where we take part in shaping every aspect of it while, at the same time, we are increasingly made strangers to its outcome — an insight that was at the core of Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism.

The growth of commodities is, from this standpoint, not the reflection of an endogenous growth of needs, but rather serves as an “alienated force,” a “power independent of the producer,” i.e., the expansion of capitalist production. That’s why, under capitalism, as Marx noted in his 1844 manuscripts, “the need for money is therefore the true need produced by the modern economic system, and it is the only need which the latter produces.”

In the second model envisioned by the Goodmans, rather than being privatized, the question of needs is at the core of democratic life. Investment decisions are no longer guided by the impersonal compass of profit but through political deliberation. Whether we want to work less or produce more cannot, in such a system, be decided through a single unit of measurement like prices. The desirability of one option over another depends on irreducible value judgments about worth. Such a democratic process compels us to choose between what the Austrian philosopher and economist Otto Neurath called different “institutional orders of a society.”

When decided collectively, the purpose of the economic apparatus cannot be made through the compass of profit; it thus always remains a political issue. When the economy is democratized, “it is not possible,” Neurath added, “to create an order of life which takes equal account of different views as to the best distribution of pleasures.” A “purposive” social order is one where society itself consciously sets its aims. Politics becomes a conflictual activity through which humans struggle to define their needs and, therefore, govern history.

Predistribution and Redistribution

While the two models outlined above aren’t descriptions of real social formations, they help us grasp the difference between institutional tools designed to allow society to increase its control over itself and those that don’t. What the Goodman brothers had in mind, they insisted, were “not plans” but “models for thinking about the possible relations of production and way of life” — the more or less democratic means by which a society sets its own rules.

Within capitalism, debates about policies focused on predistribution or redistribution are, in fact, centered on whether or not to limit the centrality of the price system as the dominant compass of the social order. Redistribution, a key demand among left movements around the world since the 2008 economic crisis, aims to alter the outcomes of market transactions to reduce income inequality. However, focusing on this aspect risks leaving the political sphere structurally subordinated to the economic sphere. This limits us to an a posteriori adjustment to capitalist production, making a society with more equal consumers without ever questioning the nature of what is produced. Marx referred to this type of orientation as “vulgar socialism” as it took “from the bourgeois economists the consideration and treatment of distribution as independent of the mode of production and hence the presentation of socialism as turning principally on distribution.”

Acting on predistribution, on the other hand, implies the more radical ambition to enhance society’s ability to define social aims. Predistributive policies, which one might see as acting a priori of market transactions, include a wide array of tools such as collective bargaining, socialization of investment, comprehensive public services, and price controls. These measures increase workers’ power to shape the division of labor and work conditions, and to orient production toward collective aims such as public childcare or control of the housing market. They politicize the question of needs not as a quantitative issue (income distribution) but as a qualitative one (consciously defining worth). They prompt us to purposefully decide, for example, if we want more health care or space tourism. What is being radically transformed in the predistributive mode is therefore not the purchasing power of various classes, but the very structure of needs promoted by the economy.

This contrast was articulated by the economist John Kenneth Galbraith in his 1958 bestseller The Affluent Society. The causes of poverty in America, he thought, were tied to the “inherent tendency” in capitalist countries for public services to “fall behind private production” — the imbalance, in other words, “between the supply of privately produced goods and services and those of the state.” The result was cities “that are badly paved, made hideous by litter, blighted buildings, billboards and posts for wires that should long since have been put underground,” but where everyone has an “air-conditioned, power-steered and power-braked automobile.”

But far from a simple plea for public investment, what Galbraith promoted was a more radical criticism of growth and consumerism for its own sake. What matters, especially as the national income grows, is what he called the “social balance” between public and private investment — that is, the balance between two fundamentally different mechanisms for developing and constituting our needs, prices vs. democracy.

A society in which private production tends to overcome public production is also one that curtails the possibility of expressing purpose collectively. It’s therefore not a criticism of consumer choices per se (as if there were objectively correct and incorrect choices) but of the inherent tendency that a capitalist society has to deny citizens the ability to allocate part of the national income through collective decision-making.

In place of a price system and sovereign consumers, such democratic tools allow people to fully participate in decisions about production and expand the sphere of citizenship. Such a break with the classical political economy, asserting the dominance of production over consumption, expands the realm of politics as a conflictual activity to control over the very purpose of the social order. In its most radical form, this approach implies that the state as a collective decision-maker could replace a posteriori adjustment of production resulting from market exchanges with an a priori political definition of needs.

Over the past fifty years, however, the ideal of self-government at the core of the socialist project has been progressively hollowed out and reduced to transforming the way we share the cake. We have been focusing on redistribution while abandoning the ambition of consciously orienting the economic process. States have boosted the fiscal apparatus to tame the effects of inequality while, at the same time, they have slowly dismantled the architecture of the postwar welfare state — especially where it altered the power relations between capital and labor.

If a more equal consumer society is preferable to an unequal one, the privatization of needs has accelerated the ever-growing colonization of social life by the market. “The pursuit of material goods,” the American economist Robert Heilbroner once noted, “diverts our attention for a time” but doesn’t offer an alternative to the “hollowness at the center of a business civilization.” As consumers, citizens can revolt against rising taxes or prices, but as producers we have more or less abandoned any ambition to collectively act on what and how we produce. At the end of history, the last man is above all a consumer. But it’s only by truly raising the question of value in human affairs that society could, as Heilbroner hoped for, offer “norms of behavior, shared moral standards, [and] a unifying vision of its destination.”