Karl Marx Looked Forward to Revolt Against Europe’s Empires

Some critics have accused Karl Marx of forcing world history into a narrow framework that presented European capitalism as a universal development model. A closer look at Marx’s late writings show how far removed that stereotype is from the truth.

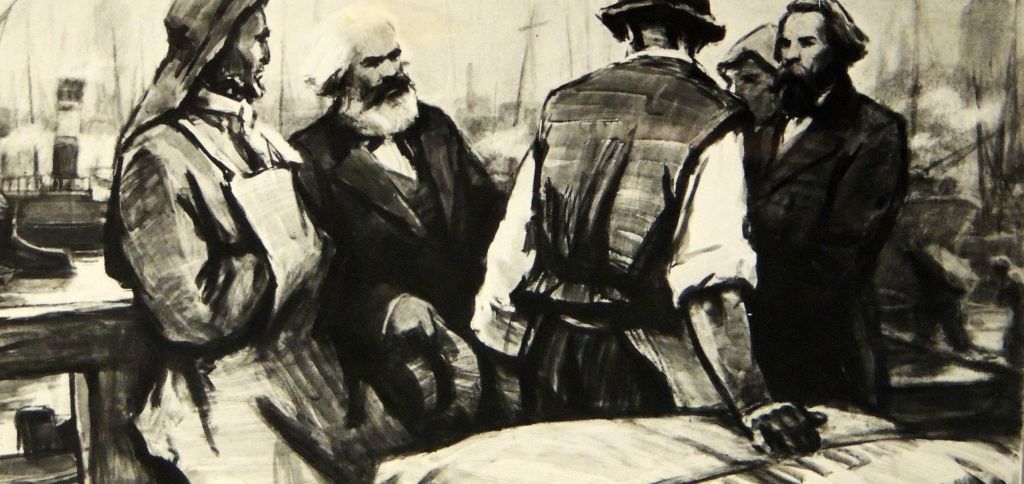

You might think there’s nothing new left to uncover in the work of Karl Marx. But Marx scholarship is just beginning to uncover the remarkable insights from his study of non-European societies and the new perspective on history he developed as a result. (Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

In his new book Karl Marx in America, Andrew Hartman suggests that we are now living through the “fourth boom” of Marxism in the English-speaking world. While such an idea might seem fanciful in terms of social and political movements, if we take it as referring to intellectual engagement with Karl Marx’s thought and writings, it captures a definite truth.

Last year, Princeton University Press published the first new English translation of Capital: Volume I in decades, while Kohei Saito’s Slow Down: The Degrowth Manifesto was published to much fanfare. In 2025, Hartman’s own book is making waves, and Kevin Anderson’s The Late Marx’s Revolutionary Roads now appears to demonstrate the continuing relevance and appeal of Marx and Marxism.

A Multilinear Marx

Revolutionary Roads takes up where Anderson’s previous book Marx at the Margins left off fifteen years ago. The publication of Marx at the Margins constituted a landmark development in Marx scholarship. Drawing on Marx’s extensive journalistic writings, letters, and late notebooks on non-European and precapitalist societies, it challenged the widespread view of Marx as a deterministic thinker with a unilinear model of history that exemplified, in the words of Edward Said, an “homogenizing view of the Third World.”

Anderson showed that Marx’s writings, when taken in the round, do not evince a unilinear and deterministic understanding of human history and culture. In fact, one can find a much more open, multilinear account with a keen appreciation of human diversity. Revolutionary Roads expands and refines this picture.

The book is based on access to previously unavailable documents, secured through Anderson’s collaboration with the Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) project. These include notes written in the last few years of Marx’s life on the anthropological works of Lewis Henry Morgan, Maksim Kovalevsky, and others.

The theme of multilinearity is central to Revolutionary Roads. In particular, Anderson interrogates the notion of “progressive epochen” — the idea of successive stages of human society, based on what Marx would come to describe as distinct “modes of production.” Marx and Frederick Engels first articulated this schema in The German Ideology (a work composed in 1845–46 that remained unpublished in their own lifetimes).

It posits a series of stages of historical development marked by movements from one dominant mode of production to the next, with the tribal or clan mode of production giving way to the ancient slave mode of production of Greece and Rome, to be supplanted in turn by the feudal mode of production, the bourgeois mode of production and then, finally, the communist or socialist mode of production. The issue of feudalism — in particular, whether we can generally describe precapitalist class societies across the globe as “feudal” — is pivotal to Anderson’s argument.

Understanding Feudalism

The very idea of such a schema has been a point of contention in Marxist studies and beyond, given its apparent affinity to Enlightenment forms of “stadial theory.” As Anderson points out, however, the whole notion of modes of production as progressive epochen is underdetermined in Marx: either we can speak of them as being progressive in a technological sense, representing a sequence of technological or social developments upon one another, or as progressive in the sense of following one after the other on a temporal scale.

There are problems with both interpretations. When it comes to the first, Anderson notes how Marx’s discussion of feudalism is laced with barbs at Enlightenment progressivism that render this reading implausible. So far as the second is concerned, the fact that Marx spoke about an “Asiatic mode of production” that stood outside the European pattern of development altogether throws the whole schema into disarray.

In any case, by the time of Capital, the language of progressive epochen disappears completely. Indeed, when we consider all of Marx’s writings, letters, research notes, and so on, in which the discussion of feudalism actually occupies a quite restricted space, it would, as Anderson notes, “be doubly wrong to consider the early communal, the ancient Greco-Roman, and the Asian modes of production as somehow peripheral to Marx’s work, while making feudalism central to it.”

In Marx’s ethnological notebooks, and in some of his later wrings, including the French-language edition of Capital, we see him at pains to criticize the universalization of European feudalism to cover the history of non-European societies. Anderson demonstrates Marx’s own trajectory of study, which indicates that he was in the early phases of a significant engagement with the structures and scope of non-European societies, one that might have become more central to subsequent uncompleted volumes of Capital, particularly the mooted volume on the world market.

In his 1877 response to an article in a Russian journal that critically commented on the historical sketch of “so-called primitive accumulation” offered in Capital: Volume I, Marx takes direct issue with the author, a Mr Zhukovsky, who he complains “feels himself obliged to metamorphose my historical sketch of the genesis of capitalism in Western Europe into an historico-philosophic theory of the general path fatally imposed upon all peoples, whatever the historical circumstances in which they find themselves.”

We can also find evidence for Marx’s rejection of this unilinear reading in a passage that Anderson quotes from the later French edition of Capital:

But the basis of this whole development is the expropriation of the cultivators. So far, it has been carried out in a radical manner only in England: therefore, this country will necessarily play the leading role in our sketch. But all the countries of Western Europe are going through the same development, although in accordance with the particular environment it changes its local color, or confines itself to a narrower sphere, or shows a less pronounced character, or follows a different order of succession.

Social Labor

A related issue is the importance of Marx’s study of communal property relations — or, rather, as Anderson puts it, “communal social relations” or social forms. This distinction is no exercise in hairsplitting on Anderson’s part. As he notes, it would be mistaken to say that Marx focused on communal property per se in his studies of non-European societies, since several of those societies “had little in the way of property of any kind, save small amounts of personal property.”

More significantly, it is the form of social labor used to sustain society, rather than property forms themselves, that is the most essential concern for Marx. Property forms function more as secondary characteristics that are derived from this prior form.

The distinction is helpful, not least in dispelling the argument found in the work of Proudhon and others that depicts property as a form of theft. For Marx, the notion that “property is theft” rests on an elementary confusion: we can’t speak of “theft” in relation to something that was not property in the first place. For something to be stolen, it must first belong to someone else.

As such, Marx argues that property relations are the result of a process of transformation of wider social relations and the role of labor: in particular, the violent process of the separation of producers from direct access to means of production, and their enmeshment in new social relations (i.e., as slave- or wage-laborers). Only then can we have private property as an enduring form of social relation.

Marx expounds upon this in the final Chapter of Capital: Volume I, “The Modern Theory of Colonisation,” which appears in the section devoted to “so-called primitive accumulation.” In this chapter, Marx recounts the sad story of Mr. Peel, an English industrialist who misunderstood the human desire for unalienated labor.

Mr. Peel had transported the means of production and a gaggle of prospective wage-laborers to Swan River, Western Australia, supplying all that was required for an incipient enterprise to establish itself. To what was no doubt Mr. Peel’s great horror and indignation, the prospective wage-laborers promptly deserted him upon arrival at their destination. They struck out on their own, exercising the elementary right to self-determination of the daily reproduction of their conditions of existence.

There is a long-running debate about whether we should see “so-called primitive accumulation” as either a historical or a continuous process. Was it restricted to the period when capital emerged through a strange process of alchemy out of non-capital — capital’s “pre-history,” as Marx calls it? Or is it an extended phenomenon, exemplified by the continued development of capital into zones of non-capital, right up to the present?

As Anderson shows, Marx’s notes depict advanced, mature capital accumulation as functioning alongside, and necessarily requiring, overt state violence to transform communal social relations. India is a clear example, and to a lesser extent Algeria, but it is notable that Marx also discusses it as an impending historical phenomenon in the case of Russia. As Marx states in his letter to Russian populist leader Vera Zasulich: “what threatens the life of the Russian commune is neither a historical inevitability nor a theory; it is state oppression and exploitation by capitalist intruders.”

Communal Forms

One of the themes of Revolutionary Roads is Marx’s keen attentiveness to resistance to colonial rule. Of particular importance here is the role of “rural communes” — Marx comments not only upon the rural communes of India, but also those of Algeria and the Americas. His praise for such resistance seems to contrast with earlier comments in an 1853 article of Marx’s that described the “primitive” village commune as “the solid foundation of Oriental despotism,” with colonialism playing a progressive role in bringing about its dissolution.

Anderson previously discussed this point in Marx at the Margins, where he contextualized those comments and demonstrated Marx’s progressive shift towards a more directly anti-colonialist position over the following years. In his new book, he provides a deepened sense of how Marx developed this anti-colonial position. This is especially apparent in Marx’s fascination with the persistence of communal social forms, from Russia to Ireland and even Germany.

Reading Anderson, we get the palpable sense that Marx sees communal social forms, even where only vestigial elements remain, as being pivotal for understanding “the negation of the negation” of capital, suggesting the form of the future communist society. It is no coincidence that Marx’s study of the traditional commune intensifies in the years after the Paris Commune of 1871.

It would be wrong to see Marx’s interest in the ancient commune as a romantic identification with such archaic forms. Anderson shows Marx subjecting the patriarchal elements of those forms in particular to stringent criticism, at the same time as he praises their more progressive elements. In fact, it is not the ancient communal forms in their precolonial versions that are Marx’s main concern.

Taking India as a case in point, Anderson notes that the “key dialectical juncture” for Marx’s theorizing comes “after the substantial penetration of British colonialism, after these communal forms were disrupted by aspects of capitalist social relations imposed by the British.” Marx is preoccupied, he believes, with how this process initiated “new types of thinking and organization that can form the basis of a new type of subjectivity,” one that will prove dangerous for the colonizing forces. If this was indeed Marx’s observation, then it shows undeniable prescience in the light of twentieth-century history, with its myriad anti-colonial revolutions.

Roads to Revolution

Anderson’s concluding chapter is in many ways the ultimate focus of the book, where he broaches the question of Marx’s understanding of revolutionary transformation and how it shifted over time. Up until at least the mid-1850s, it is evident that Marx viewed industrially developed nations such as Britain as the likely locus of revolution, which would then spread to the peripheries of capitalism in countries like Ireland and Poland.

By the late 1860s, however, he had come to reverse this view, arguing that it would be in and through events in Ireland that revolution would be sparked in Britain, from where it would spread through the world. In Revolutionary Roads, Anderson demonstrates how Russia later came to assume for Marx the place of Ireland and Poland as the touchstone of world revolution.

A letter to the French socialist leader Jules Guesde from 1879 makes this clear: “I am convinced that the explosion of the revolution will begin this time not in the West but in the Orient, in Russia.” According to Marx, revolution would spread first from Russia to Germany and Austria:

It is of the highest importance that at the moment of this general crisis in Europe we find the French proletariat already having been organized into a workers’ party and ready to play its role. As to England, the material elements for its social transformation are superabundant, but a driving spirit is lacking. It will not form up, except under the impact of the explosion of events on the Continent.

At the same time, the ancient commune becomes central to Marx’s thinking on revolution itself. The Marx that Anderson shows us in his last years is at pains to reject the notion that developments in Britain and Western Europe must be replicated everywhere in order for the transition to communism to be possible. He clearly suggests that a socialist future can emerge from the village communes if the influences bearing down on them from capitalist encroachment can be overcome:

Can the Russian obshchina, a form, albeit heavily eroded, of the primeval communal ownership of the land, pass directly into the higher, communist form of communal ownership? Or must it first go through the same process of dissolution that marks the West’s historical development? The only answer that is possible today is: Were the Russian revolution to become the signal for a proletarian revolution in the West, so that the two fulfill each other, then the present Russian communal landownership may serve as the point of departure for a communist development.

A final contribution Anderson’s study offers is the foregrounding of central themes from Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program, a new edition of which Anderson cotranslated with Karel Ludenhoff in 2023. This edition, with an excellent introduction by Peter Hudis, focuses on the problematic translation of the German term Staatswesen (“body politic”), which has been rendered incorrectly in most English translations as “state.” As Ludenhoff and Anderson note, Marx’s account of the future communist society is premised on the replacement of the state with the direct democratic control of the necessary “state functions [Staatsfunktionen].”

It is for this reason that Marx spoke of the commune in The Civil War in France as “a revolution against the state” and “the reabsorption of the state power by society as its own living forces.” Marx leaves the precise process by which the Russian commune and the industrial West would interact to modernize the commune form somewhat unclear in these late writings. Yet taken together, they should disabuse us of the idea that he saw a statist form of socialism as the alternative to capitalism.

Anderson’s study reveals a Marx markedly different from the dogmatic figure that so many critics and admirers alike have portrayed, one whose flexibility of thought, inspired by attentiveness to practices on the ground as well as immersion in a wide range of scholarly reading, should be taken far more seriously. Revolutionary Roads implicitly calls us transpose Marx’s practice to our own moment, paying close attention to different social practices and possibilities, looking not only for the evidence of regression so apparent all around us but also for the many forms of resistance to it.