Economic Insecurity in the US Has Gotten Worse Since COVID

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the US government created a formidable but temporary array of social programs that led to a sharp decline in economic insecurity. Since then, Americans’ economic insecurity has only gotten worse.

In the US, crisis-level economic anxiety is the new normal. (Robyn Beck / AFP via Getty Images)

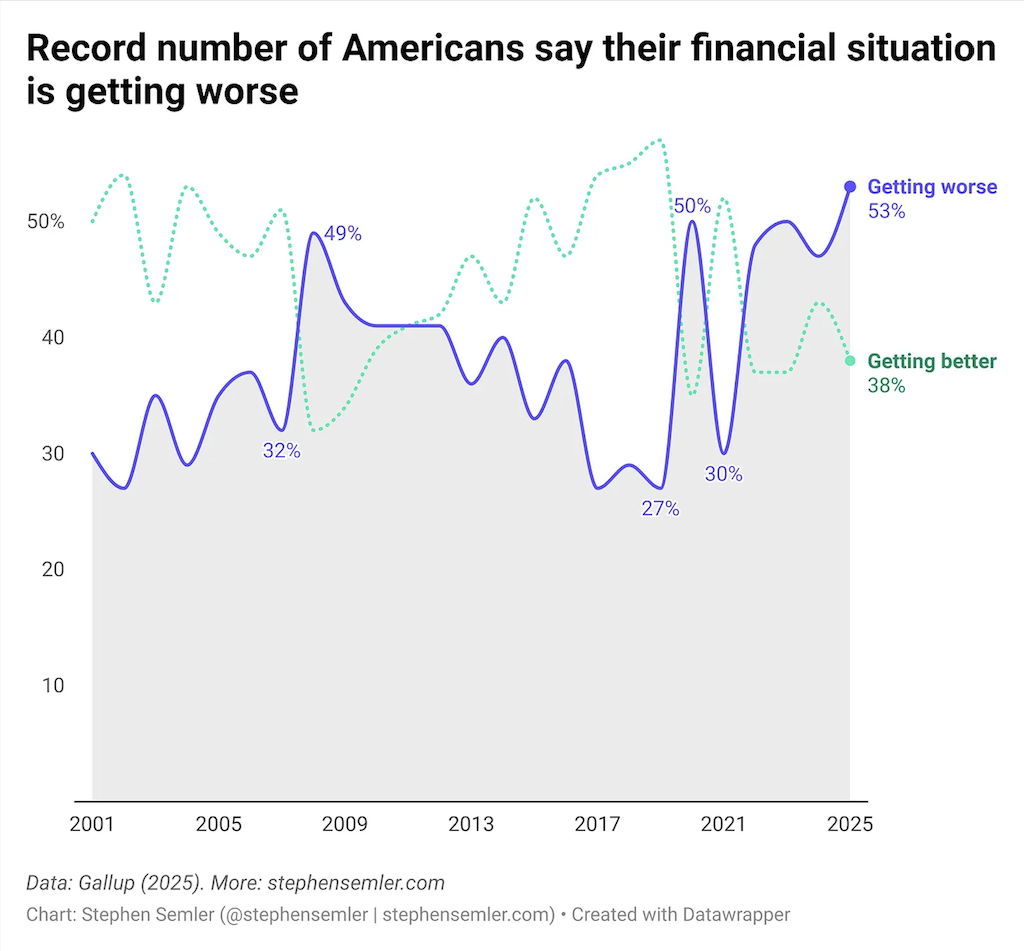

Since 2001, Gallup has asked US voters whether they think their financial situation is getting better, staying the same, or getting worse. This year, a record number of Americans answered, “getting worse.”

The 53% who said their financial situation is deteriorating surpasses the 49% who said so during the 2008 financial crisis. Responses have come within 5 percentage points of that mark just five times, and every one of them was in this decade. Crisis-level economic anxiety is the new normal.

The knock-on surveys about economic anxiety is that respondents’ answers are often shaped at least partly by their degree of optimism or pessimism about the future, and those sentiments are strongly influenced by partisanship. Members of one political party generally feel better about things when their party is in charge, and vice versa. For example, 25% of Republican voters in 2024 said their financial situation was getting better, but in 2025, 61% did (+36). At the same time, the share of Democratic voters feeling good about their financial prospects fell from 66% before Donald Trump was elected to 16% after (-50).

Out of politeness, let’s describe this partisan-obedient behavior as interesting, even though many of us actually think it’s moronic. So why take the data seriously at all? Because despite people’s interesting behavior, the data somehow still ends up making sense; as a whole, the anxiety is justified. The percentage of Americans who said their finances were getting worse shot up in 2008 (as it should, considering the financial crisis) and in 2020 (as it should, given the pandemic). The percentage falls when it’s supposed to, too: in 2021, the share reporting deteriorating financial conditions dropped by 20 percentage points. That happened because the United States stumbled into building an almost European-level welfare state through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act or CARES Act (March 2020), Consolidated Appropriations Act (December 2020), and American Rescue Plan (March 2021). The result was a disjointed but formidable array of social programs overlapping in 2021, which led to a sharp decline in economic insecurity.

Economic Insecurity

Economic insecurity isn’t the same as economic anxiety, but it’s close. Economic insecurity means being unable to reliably cover your basic necessities. Economic anxiety is distress from experiencing economic insecurity or feeling like you’re headed toward it. The former is an objective, material experience; the latter is a subjective, emotional response to that experience. It’s being insecure versus feeling insecure.

I like economic insecurity (as a concept) for a few reasons. First, it accounts for the vast but often ignored material hardship that exists above the poverty line. Second, it’s relevant. Like inequality, insecurity is liable to harm everybody but the wealthy. Third, it’s relatable, possibly even more than inequality. In my experience, people interpret their economic situation primarily by gauging how their resources align with their needs, not how their resources compare with someone else’s. Polling is required to say for sure, but I suspect the public feels more insecure than unequal.

Last election, Republicans capitalized on the widespread sense (and reality) of economic insecurity. A smart play, considering it was voters’ number-one issue. Nominally, “the economy” was the top concern, but most voters evaluated the economy in terms of the difficulty of living in it — that is, the spiraling cost of living mattered much more than the state of the stock market or GDP or even unemployment.

Democrats largely refused to acknowledge that rosy economic conditions at the national level allowed for pervasive misery at the human level. Liberal pundits claimed that widespread economic anxiety was simply bad “vibes” — something that only existed in people’s heads, the result of either partisan brainwashing or low self-esteem. I remember seeing oily and misshapen Gen Z influencers tied to the administration parrot this take on social media, always in a condescending tone, and wondering whether Democrats were trying to lose.

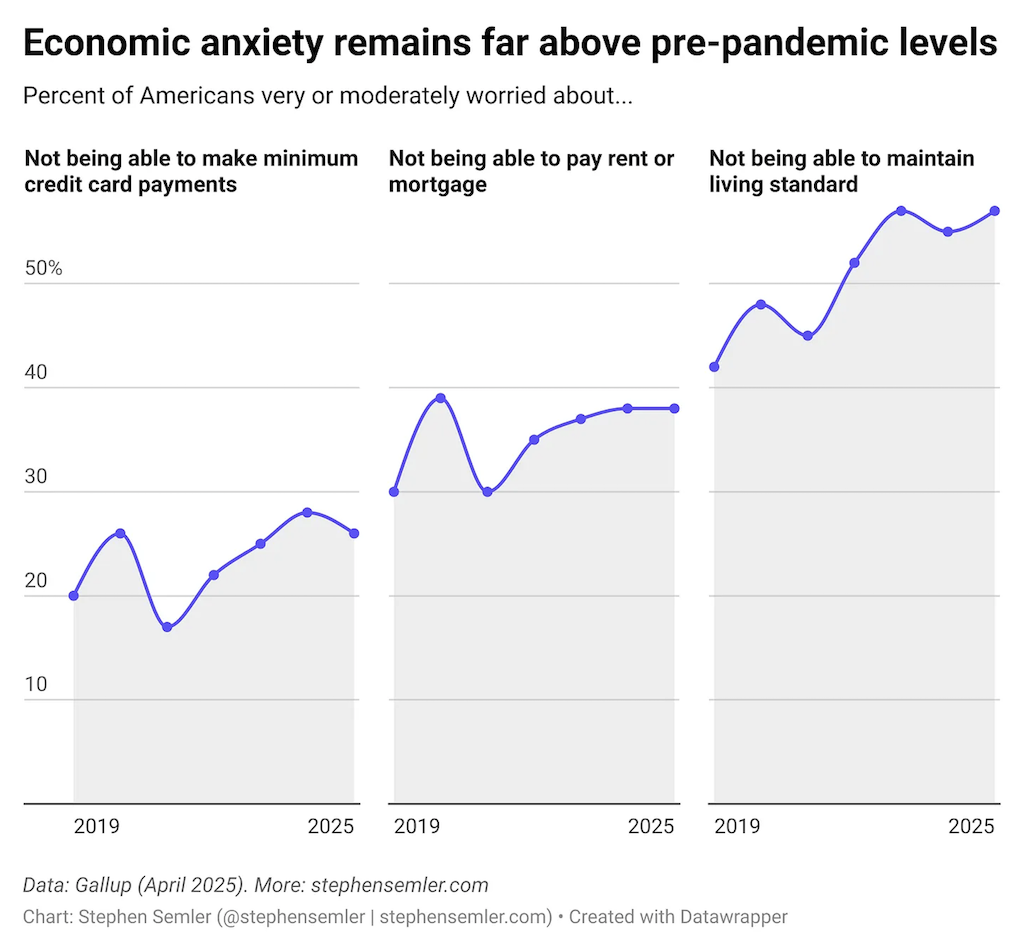

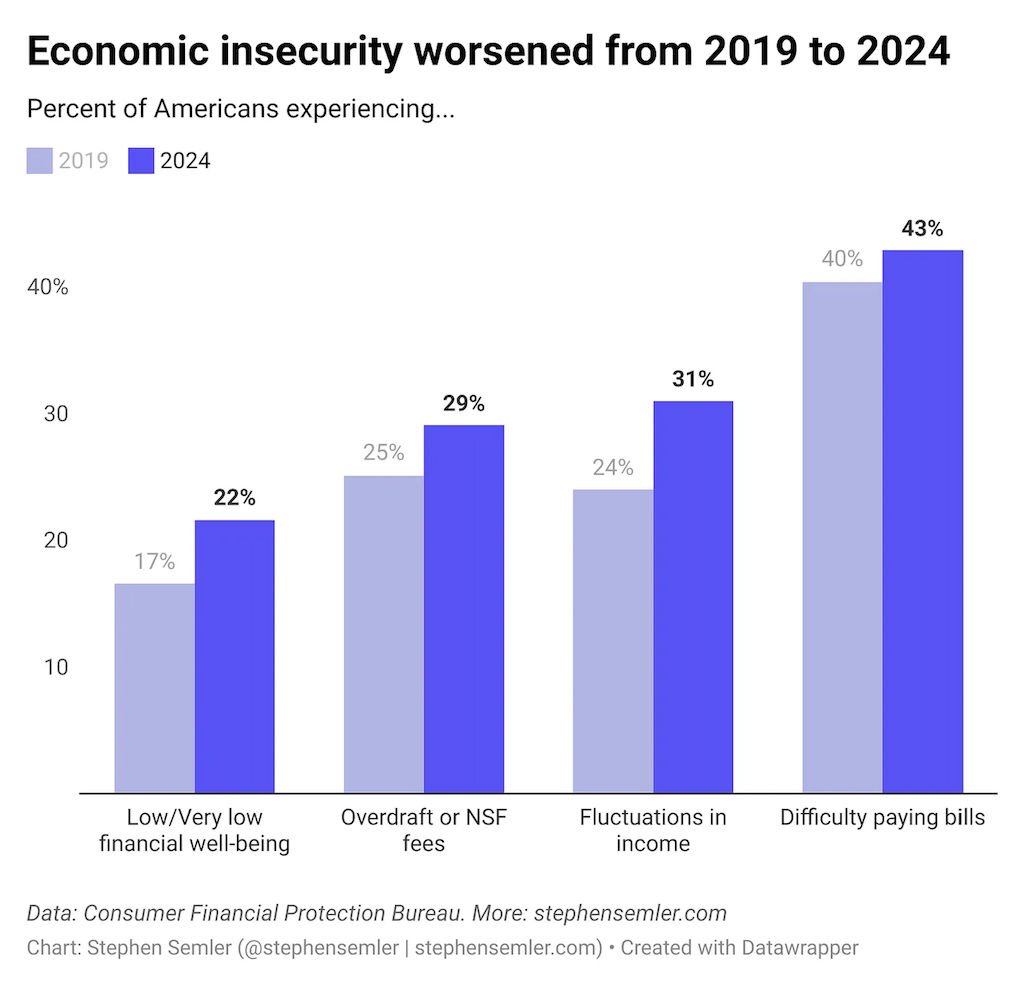

Pathologizing economic anxiety turned out not to be a political winner for several reasons, the biggest one being that anxiety was a perfectly reasonable response to economic insecurity, which there was plenty of. There are two charts below. The first shows that economic anxiety hasn’t retreated to pre-pandemic levels. The second graph helps explain why that’s the case — there’s more subjective anxiety because there’s more objective insecurity. The reason so many people think they’re worse off compared to before the pandemic is because they are.