Why the Left Should Care About Population Decline

Population decline is not just about human extinction. Before it ends, human civilization will grow increasingly unpleasant — and communal ideals associated with left-wing politics will become increasingly difficult to sustain.

The population-decline scenario is one where life gets worse and worse long before it ends. (Deb Cohn-Orbach / UCG / Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Much of the current talk about population decline fixates on how low birth rates ultimately doom humanity to extinction. The demographic math is grim. To simplify, imagine a population of one hundred and a total fertility rate of around one child per two adults, as in parts of East Asia and Europe. The next generation has fifty people, then twenty-five, twelve, six, three, and that’s that. It takes time, but the trend reflects exponential population decay and a slow fade from history.

There is a debate brewing on the Left about how much we should care, with some contending that population decline is a serious problem and others unruffled by the matter. Liz Bruenig summarizes one side of the debate this way:

Should humankind continue? If the answer is yes, then we’re already dealing in the realm of pronatalism, where the good of childbearing is taken for granted—and differences in approaches would likely come down to policy particulars. But if the answer is no, then all of politics is moot anyhow. The cause of humanity’s future is too important to cede to a political right with questionable intentions, or to be ignored.

Nathan Robinson voices a different perspective:

Personally, I do not think it is obvious that we have any obligation to ensure humankind continues indefinitely. . . . If the human population shrinks over time, it is a matter of perfect indifference to me. I want the people who do exist in the future to be happy and to live well, but I have no opinion on how many people there ought to be. If, in the very long run, our species goes extinct, I do not think that is a matter of moral concern.

Robinson’s position is interesting, and it might be reasonable to care little about the extinction of humanity. I would personally feel a lot happier about a million years of communism, but one can grant that it is a bit of an airy debate.

Set humanity’s eventual demise aside for a moment, however. Robinson says that he wants “the people who do exist in the future to be happy and to live well,” but this is not how it will transpire. Long before any final extinction, unmitigated fertility decline will cause humanity’s prospects to grow dimmer and the remaining people’s lives to grow increasingly difficult and unpleasant.

There are four major reasons to foresee such erosion. First, the welfare state becomes harder to fund as the number of claimants increases and the number of payers decreases. Second, large collective projects become harder to fund because their costs are fixed and must be divided by a smaller and smaller group of people. Third, a smaller group of people means that the good things that come from specialization can be lost. And fourth, the factors above, and other ones listed below, mean that a declining population may be a less solidaristic one.

The end will not be a bolt out of the blue, like the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. No, the population-decline scenario is one where life gets worse and worse long before it ends.

A Camping Trip Gone Terribly Wrong

Let’s explore these dynamics in microcosm.

In his little miracle of a book Why Not Socialism?, Marxist philosopher G. A. Cohen invites the reader to imagine society as a camping trip with a group of friends.

They set up camp, share equipment, split chores, and enjoy meals together. What Cohen wants us to observe is that this familiar and intuitive way of organizing a trip mirrors the core principles of socialism: shared ownership, mutual aid, and distribution based on need. It would be strange for a camper to find success fishing one morning and then consume the trout alone. And it would be strange for another camper to discover an apple tree and then build a fence and charge the others for access. Socialism is a sensibly organized camping trip, while capitalism is a poorly organized one.

Cohen’s society-as-camping-trip analogy is also useful for understanding the problems introduced by population decline. Let’s imagine a camping trip with a few families, thirty or so people, who’ve gone camping together every summer for as long as anyone can remember.

But in our scenario, the number of campers begins to decline precipitously, with a dwindling proportion of children and a growing proportion of seniors. This is precisely what happens to society as populations decline. And in the case of the camping trip, we can see clearly how it causes the arrangement to come unglued. Over time, as a result of these changes, the trip becomes more burdensome, less fun, and eventually quite bleak.

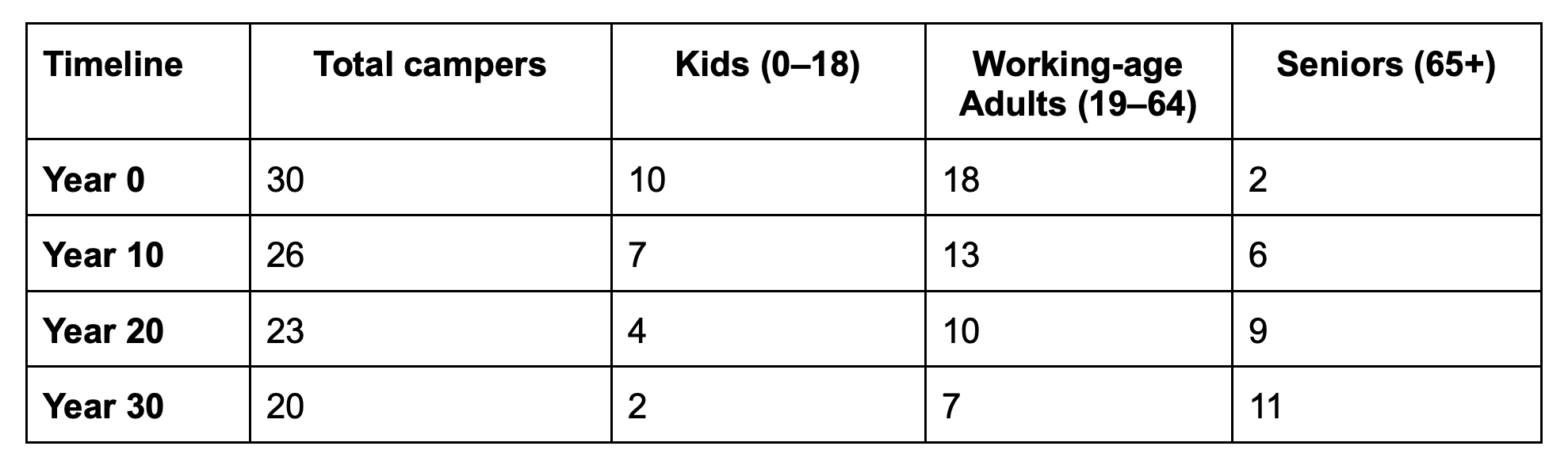

To visualize the scene, I’ve mocked up some contrived numbers in the table above. The implied birth rates are too low, and this is not even the kind of toy model that demographers call a “cohort-consistent” projection. Still, the stylized numbers capture the core dynamic: under standard textbook assumptions, a society with very low fertility will both age and shrink.

We see in the table that over the years, the number of seniors grows and the number of adults falls. This means that the ratio of adults to seniors falls as the adults get steadily outnumbered. The number of kids also falls, but the overall “dependency” ratio (the number of dependents below age nineteen and above sixty relative to the number of adults) is still rising. Finally, the size of the camp as a whole falls too. We allow for some mortality and attrition each decade, but otherwise, people get older over the years, and a very low birth rate means they are not replaced.

At first, there is some balance between adults, children, and seniors. But by year ten, warning signs appear. There are fewer kids around, which might be perfectly fine for some, but it does become a less playful camping trip. And the remaining kids themselves are unhappy about it. Soccer becomes impossible; tag doesn’t quite work. In material terms, the impact is clearer: the lack of children means there are fewer adults as the years wear on. And the adults of past years get older.

There are some consequences for the distribution of work. For one, each adult has more of it. The elderly are around, but it’s hard for them to set up camp. It’s hard to go searching for wood. It’s hard to bend over to clean dishes in the lake. The working-age adults do all that, but they also have more care work to do. Some start to grumble. Everyone wants the older campers to continue participating, but their needs tend to grow, and this becomes taxing as they shift closer to the majority.

There are consequences for collective projects too. After years of camping, the group might want to make good on old plans for a big communal food shelter for shared food prep or even a fishing boat. If the campers return to the same site each summer, perhaps they want to build a composting toilet or sanitation facility. These projects become less feasible. Some plans only require resources rather than increasingly scarce physical labor, but this is a problem too: the camping trip isn’t just getting older, it’s also getting smaller, and projects with fixed costs will be divided by a falling denominator.

There are other consequences for quality of life. In prior years on the camping trip, the group was big, and the knowledge base was diverse. There was someone who knew all of the different types of plants, which was useful for foraging and avoiding poisonous leaves. Someone else was an expert in knots, useful for building shelters, securing gear, and setting traps. Another knew how to navigate by the stars when GPS failed. Someone could smoke and preserve fish for the whole week. The campers still know basic CPR, but there used to be a nurse in the mix. The campers can still cook, but there are fewer good cooks. As the group dwindles in size, the know-how deteriorates. In time, Cohen’s trip worsens; it becomes more of an expedition than a vacation.

Four Problems

The camping example clarifies the four major problems posed by population decline. The first is that the proportion of workers falls relative to nonworkers in society. Just as the trip over time becomes increasingly burdensome for working-age campers, so too does an aging population produce the real-world result where the work of society is heaped on fewer shoulders. In rich countries, the welfare state relies on a large tax base of workers, and those revenues start to dry up. Meanwhile, age-linked spending — pensions, health, and long-term care — rises mechanically as cohorts retire, live longer, and constitute a bigger portion of society. Productivity increases could soften the effect, but tax-and-transfer systems require revenue from workers, and the whole apparatus of the welfare state will strain under the twin pressures of fewer payers and more claimants.

The equivalent process inside families is straightforward. If you’re a millennial or Gen Xer, you may remember many classmates from three-child families; in your own cohort, such families are rare. The implications for care work are significant: the task of supporting aging parents shifts from three sets of shoulders to perhaps only one or two, maybe none.

Second is the issue of fixed capital investments. Just as the campers struggle to justify investments in sanitation, in the real world, big public projects suffer in the event of population decline. This is another example of how it gets worse before it ends. Ambitious projects often entail fixed costs, and when populations decline they become less affordable.

Think about subway systems. There is a reason why we find these in places like New York City and not Madison, Wisconsin. The per-person costs of these systems are too high in sparsely populated locales. A fishing boat and sanitation facility become less affordable with fewer campers, and the same will be true about a range of projects we ought to care about: public radio, new infrastructure projects, environmental retrofits, high-speed rail systems. All of these have high fixed costs that become affordable with larger populations. The bigger the population, the better in quality these projects can be.

Scale unlocks a world of goods that do not survive well in miniature. To start: centralized wastewater treatment systems, regional flood-control works, district heating, national research labs, level‑1 trauma centers and NICUs, international airports, mobile crisis teams, public recycling and composting. But also: full symphony orchestras, public broadband, public libraries with archives, big museums, late-night cafes, good and diverse food options, subculture. All of these trappings of a functional and enjoyable society get harder to maintain as populations decline.

It’s true, of course, that small is beautiful. A tiny halal butcher, a single-screen art-house theater, an anarchist library, a lesbian bar — these are lovely things. But often, small and beautiful depend on a critical mass; without size, they languish and disappear.

Third is a point about the erosion of specialized but collectively available knowledge. Recall that in the camping trip, expertise declines as the group shrinks. It is easy to see how this plays out in society as a whole. Already, small towns often lack the medical expertise required for specialized ailments and rare diseases. Declining populations means that, on the whole, we will be unable to devote our energies to narrow but useful forms of knowledge. It is a good idea to have some people devote all their time to, say, just one strain of some deadly virus. But as society gets small, all doctors become generalists, all chefs become short-order cooks, all engineers become mechanics. The tragic effects apply broadly. If we care about high-speed rail or new forms of clean energy, a bigger population facilitates the detailed division of labor and expertise to realize and maintain it.

And fourth, as time goes on, social cohesion and communal ideals can degrade. If greater burdens fall on a small group of adults, those adults may begin to defect from the group. They will ask why more and more of their labor and income should be extracted and redirected. They may abandon collective projects, and cooperative attitudes may begin to diminish. All economies require reciprocity — including but not limited to the communal ideal — but a spirit of reciprocity is founded on reciprocity in practice. And the dynamics described in the problems above point to a disgruntled working-age population: they are outvoted by an older population, their own projects are less likely to transpire, and more of their resources shift to elder care. Altogether a weakening of social cohesion makes democracy less stable.

Cohen argues that what we observe on the ideal camping trip can be called “communal reciprocity.” It is “the antimarket principle according to which I serve you not because of what I can get in return by doing so but because you need or want my service, and you, for the same reason, serve me.” Social cohesion and a sense of duty to one’s community are not the kinds of things Marxists have spent much time worrying about. They feel insufficiently materialist. But these abstract commitments are the cement of society, and they can diminish as workers come to constitute a falling share of the population.

Beyond these four problems, there are still other reasons why a society with an aging and shrinking population may become more conservative and less socially cohesive. An older population may have shorter time horizons; rationally they may not want to devote their tax dollars to big projects that pay off decades down the line. Many forms of clean energy take years to come online. Why reduce current income to fund a new hydroelectric dam or nuclear reactor that takes twenty years to come to fruition?

Additionally, setting cultural forces to the side, older people are more likely to have investments, homes, and life plans that they might not want to upset, which is why they may be more hesitant to support big social and economic upheavals. Young people are typically at the core of large-scale social transformations, and a society with fewer of them may have less energetic and perhaps less radical social movements. Moreover, political, social, and even cultural institutions may ossify: with fewer young entrants, they may be dominated by incumbents who are perfectly happy about their existing shape and who resist transformation or even experimentation.

There are still more reasons to worry: a declining working-age population could mean that the voices of labor movements grow fainter. And as populations decline, public goods will be underutilized. When subways, libraries, and public schools empty out, there will be pressure to dismantle them. These effects can be uneven: there may be hollowed-out regions where public goods disappear entirely.

Other People’s Children

The Left is uneasy about the population debate for good reason. The Right is pronatalist because they see it as a path to gain leverage on what they’re really after: reducing reproductive freedom, buttressing traditional gender norms, or ensuring that white people have enough babies to dominate the future.

These, however, are not the arguments from people on the Left who worry about population decline. And worrying about population decline need not cede ground to the right-wing projects of nativism and reproductive unfreedom. Bad arguments in favor of apple pie (it’s a crucial helping of one of the essential food groups, fruit!) do not discount the good arguments for it (apple pie tastes good). That Elon Musk wants to fund sustainable forms of energy does not demolish the notion per se.

Others on the Left argue that population decline is good because it means fewer emissions. I do not want to sidetrack too much, but on closer inspection, this appears to be untrue. In most rich countries, per capita and absolute emission levels have fallen despite growing populations in the past couple of decades. And the explosion in solar power in recent months shows that energy systems can shift much faster than population does in either direction. It is also the case that a strategy to reduce emissions by way of fertility decline will be too slow; to have an effect, this approach would have to literally delete people from the planet. Climate solutions exist in our current policy toolkit and do not require recourse to person removal.

My argument can be summarized by the view that other people’s children are public goods. This means that new people are broadly good for society; they bring benefits beyond those narrowly enjoyed by the parents.

Other people’s children can, in fact, be understood as public goods in the technical sense of the term. The term refers to goods that are (1) “nonexcludable,” meaning you can’t prevent others from benefiting from them and (2) “nonrivalrous,” meaning one person’s use doesn’t reduce what’s available for others. When left entirely to the private sphere, public goods can be underproduced, so to speak.

In the classic case, a lighthouse is a public good because you cannot exclude other boats from benefiting from the light, and when others see the light, it is not diminished. By contrast, a hot dog from a street vendor is not a natural public good — when you consume it, you can exclude others, and your consumption does sadly reduce its size. There are lots of public goods out there that are undersupplied if left in private hands: education, health, clean air, clean water, a healthy stock of fish, good-quality information, and so on. In the modern world, other people’s children qualify too.

In a recent piece in the New Yorker, Gideon Lewis-Kraus illustrated the point when he described the decline of children’s sports in South Korea. He reported on a school with a ping-pong-playing robot — when you have no friends around, kids will play with machines. Long before society ends once and for all, children’s sports will come to an end, because children’s sports depend on other children. We see this happening in our camping trip model: before society ends, friendship for children ends. This is an example of why children are public goods; their existence benefits everyone, not least other children.

This is also at the core of the points about fixed costs, the division of labor, and the welfare state: society has a stake in other people’s children in a way we do not in other people’s pets. People, even those without an interest in having children themselves, benefit from other people. In much the same way that it is better not to live on a desert island, having people around makes life good.

This way of thinking about children also contrasts with writers in the family abolition literature, who argue that the nuclear family forces all of the enjoyment and suffering of kinship into a hidden and private sphere. These authors are right to point to the importance of supporting a diversity of alternative forms of family and care. But my argument here suggests that even the private sphere of the family generates unintended benefits to the public.

With these considerations in mind, we ought to rethink public policy to make having children a lot less costly and a lot easier. This is far from a solved problem, but among other things, it requires big cash transfers to young people, especially generous and egalitarian forms of parental leave. There is no reason to think that policies that make it easier to have children cannot be built in ways that secure the autonomy and flourishing of those who are going to have them. This kind of public policy also means that government ought to build, fund, and support the construction of new homes: one of the factors behind the baby boom of the mid-twentieth century was the housing boom, which made the prospect of raising children less daunting. These kinds of policies have direct and indirect benefits: direct because they are good for people today, and indirect because sufficient scale makes for a better life for the people of the future.

Some on the Left say if society ends, it ends — so be it. But it’s not just that the human story will one day be over. As with death in organisms, things often break down first, steadily getting worse as the end comes into view. Before it ends, it gets darker, harder, less joyful.

Hell is not other people. Quite the opposite; it’s what happens without them. If nothing else, that obliges us to regard other people’s children as bound up with our own fate, meeting them not with perfect indifference but with reciprocity and solidarity.