Indonesia’s Rulers Are Whitewashing the Crimes of Suharto

In the 1960s, the Indonesian dictator Suharto was responsible for one of the twentieth century’s bloodiest political massacres. Under the rule of Prabowo, the country’s government is suppressing the memory of Suharto’s crimes while vilifying the Left.

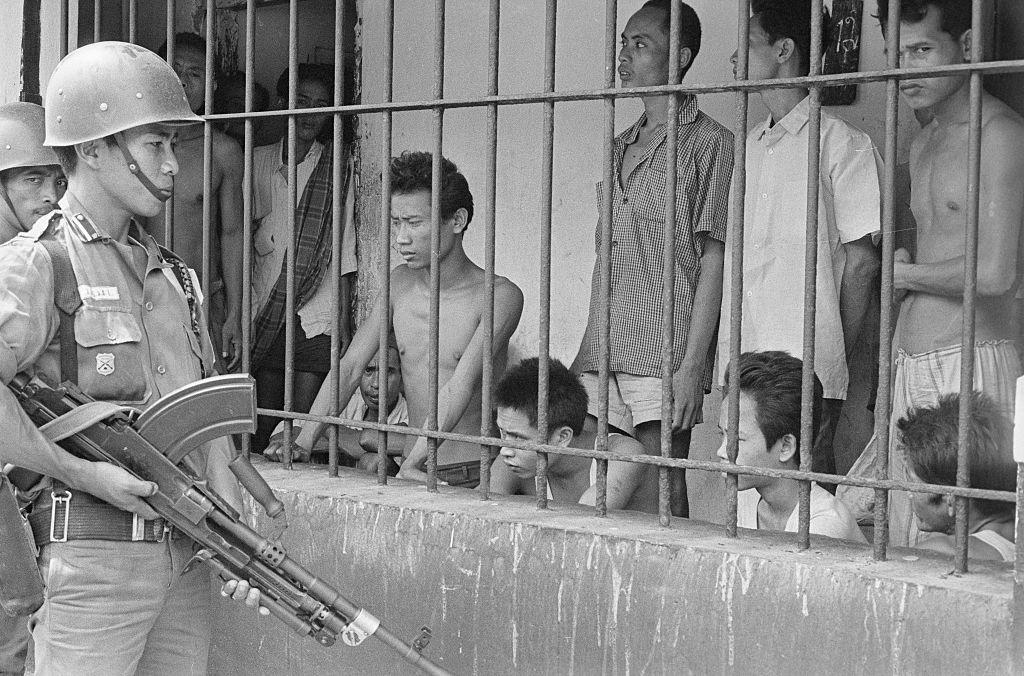

A soldier watches over suspected Communists held at Tangerang, a suburb of Jakarta, circa 1965. (Getty Images)

Working in the Ministry of Truth, Winston Smith obediently repeated the INGSOC slogan, “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.”

While I can’t confirm that Fadli Zon, Indonesia’s minister of culture, has read George Orwell’s 1984, it seems likely that he would have at least encountered it during his high school education in Texas or on his path to a PhD in Russian literature. In any case, his record in President Prabowo Subianto’s increasingly authoritarian administration has been shockingly Orwellian. Nowhere is this more evident than in his previously secret project to revise Indonesia’s official national history.

Originally set for release on August 17, 2025, a “gift” to mark eighty years of Indonesian independence, the planned ten-volume oeuvre will radically distort the historical record. Fadli’s project will consign significant contributions from women, ethnic minorities, and left-wing political movements to a memory hole, along with acts of treason and horrific human rights violations committed by prominent right-wingers.

Rehabilitating Suharto

A pro-regime student organizer under the Suharto dictatorship that held power from 1966 to 1998, styling itself as the “New Order,” the bespectacled Fadli now occupies the office of minister of culture and is one of Indonesia’s more polarizing figures. Known for his populist theatrics, far-right nationalism, and Sinophobia, Fadli has long flirted with historical mythmaking.

Now, with the launch of his controversial project to “revise” Indonesia’s national history curriculum and state-supported narratives, he is attempting something far more dangerous. It amounts to the rejection of more than twenty-five years of democratic reforms and increased academic freedom, and a return of the Suharto dictatorship’s propaganda machine. The project comes as political analysts, civil society organizations, and activists are raising the alarm about the government’s increasingly repressive actions.

Although Fadli has framed the initiative as a corrective effort to decolonize Indonesian historiography and purge it of alleged foreign distortions, it is, in fact, a thinly veiled crusade to rehabilitate the New Order legacy, demonize the Left, and entrench a narrow ethnonationalist and patriarchal vision of Indonesia’s past. In the process, it threatens to undo decades of hard-won efforts by progressive historians, civil society actors, and survivors of state violence to foster a more inclusive and democratic understanding of Indonesian history.

Bonnie Triyana, a historian and member of parliament for the opposition Democratic Party of Struggle, has expressed alarm that major events, including human rights violations, were missing from the drafts that he had seen. He stated that such a project should be an open process involving a wide range of historians and academics, rather than a government-commissioned effort. Triyana accused Fadli’s work of lacking transparency.

Asvi Warman Adam, recently retired Research Professor of Socio-Political History at the National Research and Innovation Agency, has written extensively about the political engineering of history under the New Order dictatorship and has built historiography from the perspective of the victims. The respected senior scholar has condemned the project as a politically motivated whitewashing of history to promote President Prabowo’s increasingly authoritarian rule. Adrian Perkasa, a young postdoctoral researcher currently at the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, is concerned that the project will marginalize women’s history and exclude ethnic and regional minorities in its Java-centric narrative.

Yosef Djakababa of Jakarta’s International Relations Department Universitas Pelita Harapan noted that the outline of Fadli’s project leaves out the 1958–61 PRRI–Permesta Rebellion. Originally a putsch led by disaffected colonels in Sumatra and Sulawesi against the Javanese-dominated central government in Jakarta, the movement set up the rival Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia with CIA backing, challenging Sukarno.

Sumitro Djojohadikusumo was a central leader who secured American funds for the rebels and served a minister in the treasonous regime. After over thirty thousand civilians and soldiers died in insurrection, he fled into exile. When Suharto seized power in 1966, he returned as the dictator’s chief economic strategist, running the so-called Berkeley Mafia and opening the country for US investment. The fact that he was President Prabowo’s father likely accounts for Fadli’s omission of this major event.

Ghosts of the New Order

It should come as no surprise that Fadli’s revisionist campaign places the 1965–66 anti-communist massacres at its center. These events, in which upwards of a million alleged leftists and Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) sympathizers were slaughtered and a larger number imprisoned, tortured, and raped, remain one of the bloodiest and least accounted-for episodes of the twentieth century.

For decades, the Suharto regime’s narrative, which claimed that the PKI had attempted a coup of its own and that the ensuing purges were necessary to preserve the nation, was officially enshrined as truth. In arguably the world’s most successful propaganda campaign, the New Order propagated its official history in school curricula, a robust collection of monuments and museums, feature films, and the naming of streets and airports across the archipelago — an imprint that remains to this day.

Following Suharto’s fall in 1998, this version of history came under intense scrutiny. Investigative journalists, historians, and survivors unearthed troves of evidence revealing the scale of the killings, the complicity of Western powers, and the orchestration of violence by the military and militias.

Works like Joshua Oppenheimer’s Oscar-nominated films The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, as well as The Jakarta Method by journalist Vincent Bevins, introduced Indonesia’s hidden genocide to a global public. While Westerners such as Oppenheimer and Bevins have the privilege to engage with this dangerous history without facing serious danger, many Indonesian scholars, activists, and artists have risked their physical safety to correct the historical record. The mainstream consensus seemed to be making room for this dark history.

But now, with Fadli’s project, we are witnessing a state-backed attempt to reverse that process of reckoning. His newly formed National Historical Reconciliation Council is stacked with pro-military academics, Suharto apologists, and conservative Islamic figures. It has already begun publishing white papers that downplay the scale of the violence and reassert the PKI’s guilt. In recent speeches, Fadli has rationalized the killings as a necessary cleansing to protect the Republic.

A “Patriotic” Curriculum

The most immediate impact of Fadli’s campaign will be felt in classrooms. Drafts of the new national curriculum obtained by Tempo and other independent outlets reveal a wholesale revision of the standard account of Indonesian history. The revolutionary contributions of left-wing organizations like Lekra (the Institute of People’s Culture) and the labor movement are minimized or excised entirely. The new framework recasts the role of Sukarno, once revered as the architect of a pluralistic and independent Indonesia, in ambivalent tones, presenting him as an indecisive figure whose flirtation with communism nearly doomed the nation.

In their place, the new curriculum lionizes Suharto and the military, portraying them as disciplined saviors who preserved unity in the face of Marxist anarchy. The anti-colonial struggle is reinterpreted through a lens of martial valor and cultural resilience, obscuring the complex alliances among secular nationalists, communists, and Islamic modernists that actually defined the independence movement.

Even more troubling are the changes to the understanding of colonialism. Fadli’s committee emphasizes precolonial harmony and “Asian civilizational values,” suggesting that European imperialism was an unfortunate but morally clarifying event that strengthened Indonesian identity.

This historical fantasy erases the brutal extraction of wealth and the dehumanization of indigenous peoples that underpinned Dutch rule. It also whitewashes Indonesia’s precolonial history by presenting it as a romantic fantasy of cooperation and downplays Indonesia’s postcolonial entanglements with global capitalism and Western military power.

Nationalism as Cultural Weapon

Fadli and his defenders claim that his project is a necessary corrective to “liberal bias” in historical scholarship. When grilled at a House of Representatives hearing in July, he asserted that his goal was “not to forget history, but to ensure that it serves as a constructive lesson,” and called for a focus on the “positive” side of Indonesian history.

But this argument rings hollow. Since when has Indonesia’s national curriculum ever leaned left? Even during the Reformasi period, teaching about the massacres of 1965 remained taboo. Survivors were still harassed, blacklisted, and stigmatized, and there were no significant state reparations. The truth, insofar as it emerged at all, came from grassroots efforts: oral history projects, independent documentary films, and university seminars held outside official frameworks.

What Fadli offers is not a “national” history but a hegemonic one: a state-sponsored myth of eternal unity, righteous violence, and ethnic authenticity. In this, he follows a pattern familiar across the Global South, where right-wing populists — from Narendra Modi in India to Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines — have wielded history as a weapon to silence dissent and reassert patriarchal, militarized visions of the nation.

Fadli’s invocation of “cultural sovereignty” is similarly suspect. Far from resisting foreign influence, his revisionist project aligns neatly with the interests of international capital and the Indonesian oligarchy. By vilifying the Left and glorifying military order, the revised history paves the way for more authoritarian governance and deeper collusion between the state and extractive industries. This is not about decolonizing history — it is about recolonizing it in the name of capital and control.

Erasing the People’s Memory

One of the more insidious aspects of the project is its effect on collective memory. If Fadli’s curriculum is implemented, an entire generation of Indonesian students will grow up learning a sanitized, nationalist version of their country’s past. This is a story that erases the poor, the landless, the laboring masses, and the women of Gerwani, the world’s largest feminist organization in the early 1960s, who were raped and murdered in 1965.

There is widespread concern that Fadli will try to eliminate the history of the 1998 violence against democracy activists and ethnic Chinese in the dying days of Suharto’s New Order. Prabowo, who was a general at the time, was dishonorably discharged for his role in kidnapping, torturing, and disappearing activists. In June, Fadli suggested that the well-documented mass rape of Chinese women in 1998 was merely a “rumor.” Bonnie Triyana and his colleague Mercy Chriesty Barends challenged him on this dangerous historical denial in a committee hearing a few weeks later.

This is a theft of memory, and with it the possibility of justice. Without historical truth, there can be no meaningful reconciliation. Without acknowledgement of past crimes, the victims and their descendants are condemned to perpetual silence.

And yet, as history shows us, silence can be broken. If there is a silver lining to this dark chapter, it lies in the growing resistance to Fadli’s efforts. A coalition of progressive historians, student groups, and cultural workers has begun organizing teach-ins and publishing counter-textbooks online. Survivors’ organizations are holding public vigils and reading the names of the disappeared. International solidarity networks are amplifying the alarm.

Hopefully they will seize this moment not only to oppose Fadli’s revisionism but to advance a radical vision of Indonesian history: one that centers the struggles of workers, peasants, women, and indigenous communities; one that tells the truth about imperialism, militarism, and genocide; one that equips the next generation to fight for a more just and democratic future.

History is not a dead archive. It is a battlefield, and right now that battle is underway in Indonesia. What is at stake is not merely the past, but the possibilities of the future.