Ukraine’s Forbidden Frescoes

Ukrainian painter Mykhailo Boichuk and his circle of socialist artists perished in Stalin’s 1930s repression, destroying much of the movement’s beautiful public murals in the process. Today what remains of their work is a symbol of hope in dark times.

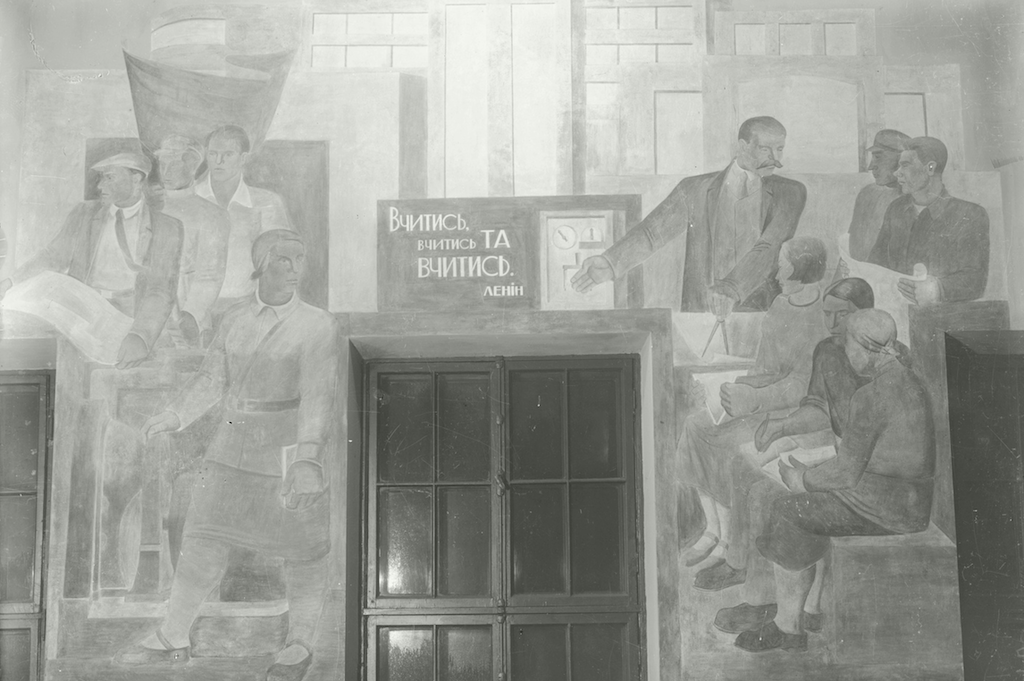

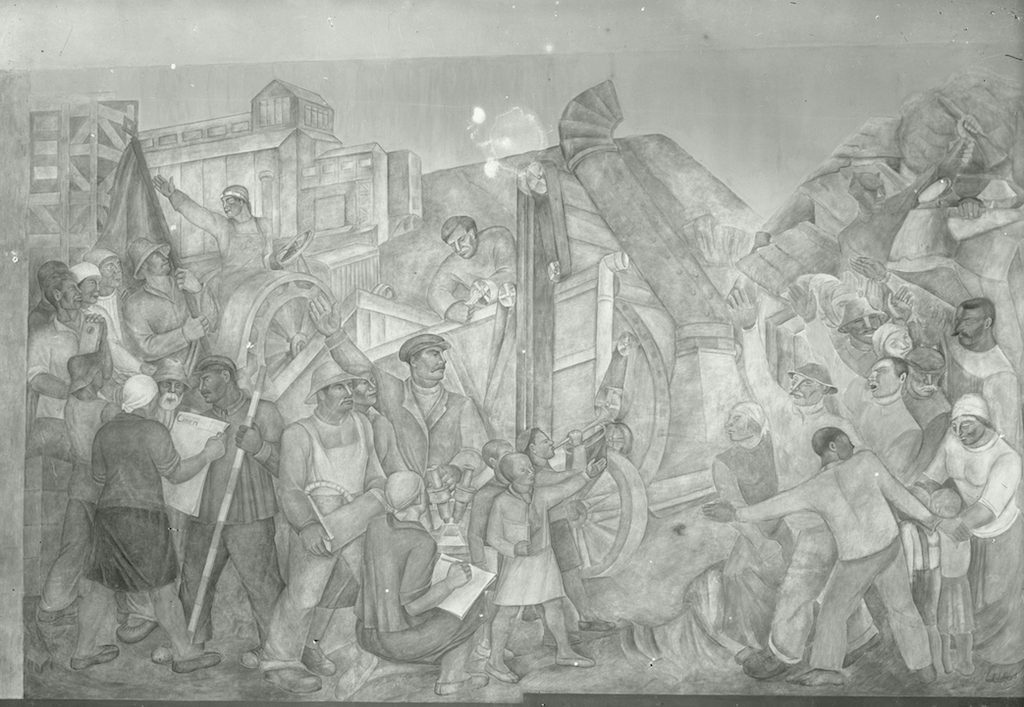

Fresco in Ukraine, ca. 1920s–’30s.

A woman’s face emerges from the many exposed layers of plaster. The cheeks have lost their glow. The crack that cuts through the fine contours and has claimed one eye is only scarcely closed with mortar. This fragment of a once much larger — but destroyed — mural today adorns a wall inside the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture in Kyiv.

Despite the regular screeching of air raid sirens over the city and the roar of explosions, the woman’s disfigured face — and the fresco’s destruction in general — is not due to the Kremlin’s current war of aggression against Ukraine. Rather, it stems from similar campaigns of violence at the hands of Moscow in the 1930s, nearly a century ago.

The wave of repression at that time swept away the Boichukists — the circle of artists behind murals like this one. As the leading figure in monumental art in Soviet Ukraine in the 1920s and 1930s, Mykhailo Boichuk had kickstarted an entire movement by this time while teaching at the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture, which he cofounded in 1917.

“Always in close collaboration with colleagues and students, he created groundbreaking murals in many places in Ukraine. Often these were epic compositions covering several square meters in sanatoria or theaters,” says Ukrainian art historian Katia Denysova from Tübingen University.

The works promote the Soviet project that Boichuk and his artist followers ardently believed in. “They created Soviet and proletarian art, but always with a local flavor. The murals were aimed at a Ukrainian audience — especially at the peasant class, which at the time made up the largest part of the population. They often used specific Ukrainian patterns or depicted the traditional costumes of villagers. It was important that ordinary Ukrainians could decode the frescoes and understand the message of progress. The Ukrainian element — the focus on Ukraine and its traditions — was typical of the Boichukists,” says Denysova.

This is not to say that the movement should be seen as narrowly nationalistic or exclusionary. “Indeed, Boichuk supported the development of internationalism through the recognition of universal aesthetic elements that he argued were present in all national forms,” writes art historian Angelina Lucento.

In a short span of years, his movement took off in a number of disciplines — above all murals and fresco paintings, which by the early twentieth century had long been forgotten.

Today, however, apart from some fragments recovered in the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture as well as in the former worker’s club of the State Political Administration (GPU) in Odesa, none of these murals survive.

“Amazing to Experience”

According to Lucento, by 1930 the Boichukists’ reinterpretation of traditional folk patterns, rural motifs, and, to a lesser extent, scenes of factories and burgeoning industrialization had made them the most influential artists in the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. Prestigious commissions to decorate new public buildings with giant frescoes poured in. While the murals support the new socialist form of government with a distinct Ukrainian profile, they hark back to motifs from Byzantine art, whose primary means of expression were in fact frescoes and mosaics, thereby creating an exciting dynamic and unique imagery.

“They must have been amazing to experience. To actually stand in front of these huge works created by some of Ukraine’s best artists. To move through the spaces and get an understanding of the proportions. Of the colors. In the preserved black-and-white photographs, it’s not always easy to get an impression,” says Denysova.

“They were commissioned to decorate an entire sanatorium near Odesa, where they created a formidable interior. They decorated walls with frescoes and ceilings with special ornaments on a grand scale. No doubt they were impressive to look at. But we no longer have that opportunity.”

The Masks Slip

Dark forces doomed the murals of the Boichukists to disappear forever. They were scraped off walls, hammered away, or painted over. The Soviet commissars went to work with such zeal that after Ukraine’s independence in 1991, local art historians and restorers have only managed to bring a few fragments back to light. A pair of uniform boots on a wall in Odesa or the face of the woman in room 250 at the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture.

When the secret police arrested the movement’s three most prominent members — Boichuk, Vasyl Sedliar, and Ivan Padalka — in the autumn of 1936, Boichukism came to an abrupt stop. During the trial of the three, the masks slipped irrevocably: the artists’ conviction that Ukrainian socialism should develop out of the republic’s own national aesthetic and not according to directives from Moscow turned out to be an illusion.

How did it come to this? Denysova searched for the answers in her PhD thesis, which she handed in last year. “It may seem surprising because to a certain extent they actually did what the Soviet regime wanted them to do. But there are several reasons: Not least because of the Holodomor, the regime distrusted the peasants as a class — especially Ukrainian peasants — and considered them disloyal and non-compliant. Therefore, art should no longer appeal directly to the rural population, as the Boichukists did. Rather, the focus shifted to industrial workers,” explains the art historian, using the Ukrainian word for the 1932–33 famine that resulted from the regime’s forced collectivization of agriculture.

“In the Soviet Union, religion was banned. The fact that they created murals with religious undertones and used a technique known from the decoration of churches, indeed, worked within a tradition of religious art, namely the Byzantine, gave them more difficulties during the interrogations,” she adds.

Russian Chauvinism

However, according to Denysova, the most important reason for the fall of the Boichukists was a third preceding factor: growing dissatisfaction in the inner circles of the Kremlin with a particularly progressive policy regarding non-Russian nationalities.

Introduced by the new socialist leadership in the early 1920s, the measure Korenizatsiya entailed a kind of affirmative action concerning the non-Russian republics of the Soviet Union. It was intended to end centuries of tsarist oppression against national minorities. The initiative laid the foundation for artistic and cultural prosperity in Ukraine, which the Boichukists both benefited from and contributed to. But the political winds shifted and during the 1930s when Joseph Stalin’s wing of the Communist Party gained more and more influence. And soon the regime’s views on art and national autonomy changed.

“It was absolutely fine for the Boichukists to create murals with Ukrainian symbolism and content in the 1920s,” says Denysova. “But when nationality politics took a different turn in the following decade, they ran into problems.”

The group around Stalin feared Ukraine’s increasingly self-conscious artistic and intellectual elite — and that the ethnic Ukrainian intelligentsia would only increase its influence in the rural population and outshine the party. This powerful faction in the Kremlin increasingly saw Korenizatsiya as a potential driving force for a counterrevolutionary and anti-Soviet uprising. From there, the need arose to control and standardize art much more effectively. And as an additional tool to consolidate his power in the Soviet Union, Stalin resorted to extensive Russification. Korenizatsiya was dismantled.

“Russian chauvinism returned. Russianness was installed as the driving force of the Soviet project in the 1930s, which the Boichukists were very much against,” says Denysova. “They believed that Ukraine had its own culture and they didn’t want to be forced to submit to Soviet Russia — or to traditions in Russian art that were different from Ukrainian.”

Ukrainophobia and Terror

Just how dangerous the regime considered Boichuk’s art to be is clear from the interrogation protocol: it contains a surprisingly multifaceted discussion of the role of art in society between executioner and victim.

“The interrogators were highly suspicious that Boichuk and his students had contact with international art movements, that they allegedly preferred Western influences to Russian ones. They accused them of really being separatists, which they claimed was reflected in their works,” explains Denysova.

During several interrogation sessions, the inquisitors asked again and again about the work of the Boichukists. They wanted to expose the allegedly bourgeois-nationalist ideology behind their frescoes and kept asking about details regarding the form and content of their motifs. Thus, the intelligence officers’ Ukrainophobia and desire to do away with Korenizatsiya not only struck Boichuk as a teacher. The specific sources of inspiration he encouraged his students to use in their works were also targeted. To the interrogators, the content of an image seemed as much a threat to the USSR as the Ukrainian artists behind it, according to Lucento. In short: the Boichukists were suspected and accused along with the particular Ukrainian forms of expression they used.

One very specific and particularly weighty accusation led to Padalka’s downfall: that he allegedly “led the struggle for Ukraine’s immediate separation from Russia.”

The trial of the Boichukists arose from a heated debate in previous years about what socialist art should look like. A radical social experiment unfolded after the revolution and the break with the Russian tsarist regime in 1917 — and a dispute about how artists should contribute characterized that time.

Secret Depots

The Soviet secret police was notorious for using the most brutal means to get prisoners to confess. And Lucento estimates that the Boichukists were probably tortured. As a rule, accusations took an absurd and paranoid form. Freely invented charges of monstrous crimes served as a thin cover for the real purpose: to eliminate anyone who might disagree with the party line, which in those years meant with the group around Stalin. It was precisely in the years 1937 to 1938, shortly after the arrest of the Boichukists, that repression in Soviet society reached an almost unimaginable extent during the so-called Great Terror. This wave of repression hit Ukraine hard.

“All Ukrainian intellectuals, who actively embraced the idea of Ukrainian autonomy — that Ukraine has its own culture and language — paid a high price for that belief because it was no longer acceptable to the regime,” says Denysova.

The inquisition against the Boichukists ended with death sentences. Boichuk, Sedliar, and Padalka were executed in July 1937 and thrown into a mass grave outside Kyiv.

Others from the movement followed. In December of the same year, the Soviet secret police executed the front man’s wife, Sofiia Nalepynska-Boichuk — an outstanding artist in her own right. Several members of the movement were sentenced to years of imprisonment in Gulag penal camps in the far reaches of the Soviet Union. The regime ordered not only the murals to be destroyed. The art movement’s graphics, drawings, and paintings were collected in secret depots — so-called spetsfondy — and annihilated. Denysova elaborates:

The repression of the Boichukists is a huge tragedy on a human level. But also on a cultural level, because Ukraine lost some of the most talented artists who could have continued to work and enrich the world around them. The fact that so many of their works were destroyed means that we have been deprived of an important part of our history as a nation. It’s a huge loss of our cultural heritage and a blind spot in our collective consciousness. We don’t have as much material about the group as we could and should have had in order to study them properly and truly admire their work.

Mutilated

A closer look at the mural fragment of the woman’s face at the Kyiv art academy reveals both innocence and beauty, despite the persistent attempts to deny her existence. The lips swell dully. Something unfathomable lies in the features. Behind the veil of pale chalk, bravery, anger, and sorrow also seem to find expression. With the missing eye, she could be one of tens of thousands of Ukrainians mutilated and disabled by the endless Russian bombardments in the Kremlin’s ongoing war of aggression.

From the murder of the Boichukists and the annihilation of their art, there is a direct historical link to the current Russian regime’s efforts to destroy Ukraine’s culture and its attempt to crush its independence. Following the invasion in February 2022, Russian forces are targeting museums, libraries, art collections, and historical monuments, among others.

“The parallel to what is happening today is all too clear. The war against Ukraine is rooted in unchecked Russian imperialism and chauvinism — in a failure after the collapse of the Soviet Union to come to terms with Russia’s imperial past and chauvinistic tendencies. They permeate the entire Russian society. This is particularly evident in the academic world, where researchers very consistently avoid fields of study such as decolonization and postcolonialism. They haven’t even begun to deal with that legacy,” says Denysova.

In the preserved black-and-white photographs, scene after scene of the murals replaces one another. Motifs of progress and freedom from oppression. Adorned by a socialist slogan. Clearly recognizable as Ukrainians and full of anticipation, children, women, and men walk toward the future. The authors pose in front of several frescoes. Brushes in their hands. Concentrated looks. Proud of their work. High above ground on improvised scaffolding. Beret on a slant. The context has changed, but their artistic ability still stands as a symbol of Ukrainian resilience and independence in dark times.