Black Workers in the US Have Been at the Forefront of the Fight for Freedom

The story of the African-American working class is the story of democratic struggle: of pairing the fight against racism with the fight against economic exploitation to push the US to become a freer and more just society.

A group of men and women gather at the Parkway Community House to discuss labor and civil rights issues during World War II, Chicago, Illinois, circa 1945. (Chicago History Museum / Getty Images)

When sixteen-year-old Minnie Savage boarded a train from Lee Mont, Virginia, to Philadelphia in 1918 with nothing more than a sandwich, she told no one of her plans. The promise of jobs and opportunity in the North was too enticing. And the conditions in Accomack County, Virginia, were especially difficult for a young black girl. Only a few years earlier, in 1907, a white mob had attacked the town’s African-American neighborhood after rumors of black laborers’ plans to demand better pay from prosperous white farmers.

Savage found work in Philadelphia. But the North had its own challenges, including many that resembled life in the Jim Crow South. Shut out of most jobs in the city, Savage was forced to toil as a cleaner at a local drugstore. The work was grueling. Each day, she scrubbed the floor of the drugstore on her hands and knees.

Savage’s experience mirrored those of millions of other black people who left the South during the Great Migration. One of those traveling to the North was Bruce Murphy, historian Blair L. M. Kelley’s grandfather. He arrived in Philadelphia around 1918, also from Accomack County.

Weaving in her family history, Kelley’s Black Folk: The Roots of the Black Working Class powerfully charts the course of the black working class from the era of slavery to the mid-twentieth century. While she acknowledges that no one book could capture the full depth and diversity of the black working class, Kelley’s book is admirably sweeping in narrative and scope. By reclaiming the stories of black workers in the United States over centuries with richness and care, Kelley’s Black Folk does justice to the memory and legacy of the countless black men and women who toiled in deplorable conditions to make a life for themselves and their loved ones.

And as Kelley stresses, this is not solely a story about individual — or family — accomplishments. It is also a story about how the labor of black people — as workers and as freedom fighters — pushed the United States toward embracing democratic ideals. “Their fights against racism and against labor exploitation,” Kelley writes, “were always one.”

From Slavery to Sharecropping to Laundry Work

Kelley begins her narrative in the nineteenth century, when four million black people were enslaved in the United States. Through the life of her ancestor Henry Rucker, an enslaved blacksmith in Elbert County, Georgia, Kelley shows the significance of community formation as a survival tactic under a vicious system that denied black people’s rights and personhood. As Kelley points out, these men and women found ways to sustain themselves by fashioning ties outside of the control of white slaveholders. During these years, Kelley argues, black people “learned the basics of what it would be like to be part of a working class by earning at the margins of enslavement.”

In the aftermath of slavery, black people were relegated to the most menial positions in US society. Sharecropping, which closely resembled slavery, left freed black men and women (as well as poor whites) in a seemingly never-ending cycle of debt and dependency. Laundry work — one of the most common occupations for black women, who made up 65 percent of the profession — was enormously taxing and poorly paid.

Yet black men and women resisted their exploitation, pushing for more autonomy and better conditions where they could. Kelley tells the story of Sarah Hill, a laundress living in Athens, Georgia, during the first half of the twentieth century, to highlight the important role of washerwomen in the years after the Civil War. Rather than submitting to demands that they work under supervision in white homes, black laundresses like Hill chose independence — they worked from their own homes, protecting them from further exploitation as well as the predations of white men.

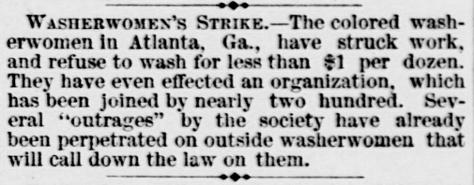

In the most well-known act of resistance, black washerwomen joined together to contest working conditions and discrimination in Atlanta’s 1881 washerwomen strike. In July of that year, twenty black women formed the Washing Society to advocate for better pay, respect, and less interference from white employers. The group quickly grew to over three thousand members with broad support among African Americans. The women maintained their solidarity in the face of arrests, reprisals, and attempts to break their control over the industry, demonstrating their ability to stand against municipal and business interests.

Kelley details other episodes in the long history of black working-class women’s labor activism. She notes, for example, how black women joined other members of the working class in Richmond, Virginia, during a general strike in 1873. She details how African-American businesswoman and teacher Maggie Lena, a daughter of a washerwoman, organized a 1904 boycott there against segregated public transportation that “bankrupted the city’s main streetcar Cottrell Laurence Dellums company.” Through these examples and many others, Kelley compellingly argues that black women have been key protagonists in the US working class.

Labor Rights and Civil Rights

The connection between black labor and the struggle for black citizenship rights is especially clear in Kelley’s discussion of the Pullman porters. Recounting the story of, one of the organizers and leaders of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Kelley shows how the Great Migration was “a search for everyday dignity.”

After almost losing a brother in the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, Dellums decided to relocate from Corsicana, Texas, to San Francisco in 1922 and search for job opportunities. On the way, he met a Pullman porter on the train west who counseled him to get off in Oakland and provided him with directions to a home where he could stay. After first finding work on a steamship, Dellums secured a position as a Pullman porter in January 1924. Three years later, he was fired by the Pullman Company for his support of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This marked a turning point in his life: Dellums (the uncle of the late leftist congressman Ron Dellums) soon became a full-time organizer for the union and ultimately a close ally of its leader, A. Philip Randolph.

Established by Randolph in 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was the first major twentieth-century union led by African Americans. Its members were workers at the Pullman Company, established by George Pullman in 1867. The nation’s largest employer of African Americans, the Pullman Company maintained a racial hierarchy on passenger trains through a tiered labor force. White conductors were placed in positions of authority, while black porters provided service to passengers on the trains.

The Brotherhood challenged low wages as well as the dehumanizing working conditions of the porters. As Kelley explains, the efforts of Dellums, Randolph, and other porters not only paved the way for improved conditions at the Pullman company. They also helped to “improve the lives of the Black working class writ large.” What’s more, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters played a central role in the creation of a national movement against racial oppression — best exemplified through A. Philip Randolph’s leadership of the 1940s March on Washington Movement and porter E. D. Nixon’s crucial organizing in the 1955–56 Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Kelley’s discussion of the Pullman porters provides a window into some of the intricacies of the black working class. As she explains, the Pullman porters may have been more educated and better paid than many other black workers of the period. Many even saw them as part of the middle class. But the economic exploitation they endured on Pullman cars, tinged with racism, placed them squarely in the working class. Within the segregated communities of the North and South, Kelley makes clear, a materialist definition of class cannot be divorced from race. While Black Folk is about the working class, its subject is living, breathing people rather than abstract categories.

She goes one step further to suggest that we also cannot ignore gender. The black domestic workers and maids who take center stage in the book — largely absent from public discourse, despite representing two-thirds of black women’s employment in the workforce in 1930 — were denied federal protections and shouldered the negative stereotypes directed at black families. Isolated from their families through live-in arrangements, black domestic workers were more susceptible to labor exploitation as well as sexual assault.

Yet black women found ways to band together — on their commutes, in what little leisure time they had, through childcare, and through clubs, churches, and unions. Motivated by the belief that “a broken America could be made better,” Kelley argues that these women negotiated for better conditions and “used what they had to craft a vision of what a better life could look like.” Black workers continually recreated the communal ties and organizing potential that sustained a culture of resistance.

The Real Working Class

In the final section of the book, Kelley turns her attention to black postal carriers. Examining the lives of Hartford Boykin, his father Isaac, and William Harvey Carney Jr, Kelley describes how federal positions opened for black Americans after the Civil War in recognition of their military service, but decades of racial violence and Jim Crow tyranny led to the relegation of black civic workers.

Black postal workers responded by creating the National Alliance of Postal Employees — first for railway postal workers in 1913 and later, in 1923, for all black postal workers. According to Kelley, this organization provided a base for black postal carriers “to center the fights of laboring men and women in broad calls for justice.” The union also lent them a layer of protection against economic retaliation, making it possible for African-American postal workers in the 1940s to help organize voter registration drives in Alabama and Georgia, and protest segregation.

With rich storytelling and innovative research, Black Folk refutes popular conceptions of the worker as universally white and male, elevating the lives of those too often ignored in media and politics. These individuals, Kelley asserts, represent “the canary in the coal mine” for the dehumanization of all laborers under capitalism, while also modeling resistance. Black workers built on the traditions of previous generations and banded together to improve social and economic conditions — not only for themselves and for their families, but for all workers across the country.