The Florida Socialists Who Knew Working-Class Solidarity Was the Foundation of Freedom

May Day is not a holiday for Florida governor Ron DeSantis, much as he might pose as a working-class champion. For a more robust vision of freedom, we can look to the Florida Socialists and Tampa cigar workers of Eugene Debs’s day.

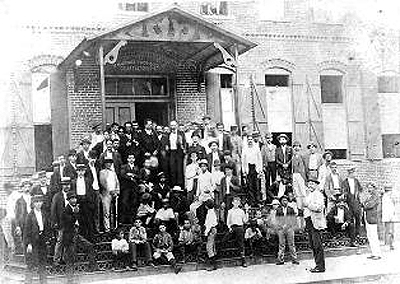

Interior of an Ybor City, Florida cigar factory, circa 1920. (Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library via Wikimedia Commons)

On a fall day in 1902, in a working-class town not far from where Florida governor Ron DeSantis would grow up, West Tampa cigar workers walked off the job to protest what they viewed as an assault on their freedom. Factory management had obstructed the cigar workers’ lector, or reader, who read to them as they crafted their highly coveted, hand-rolled product.

This was no minor affront.

The lector was the very emblem of the Tampa-area cigar workers’ proud status as free, autonomous workers. They — not the factory owners — handpicked the lector. They — not the factory owners — chose what the lector would read: novels, the news, or, most enraging to management, radical material.

The business establishment’s attack on this totemic figure — which culminated in the violent deportation of the lector himself — sent cigar workers across greater Tampa into the streets, brandishing signs in Spanish and Italian. The explosion of mass solidarity forced management to relent. The workers would keep their reader, at least for the time being.

El lector could hardly be more alien to Ron DeSantis’s Florida. While DeSantis frequently touts his working-class Italian roots, scorns well-connected elites, and drapes himself in the garb of freedom, the Tampa cigar workers would have scoffed at his anti-union, free-market populism as counterfeit liberty — a surefire way to press workers further under the thumb of swaggering employers.

Many of the cigar workers sympathized with or were card-carrying members of the Socialist Party of America. They and other Florida Socialists of the era — tenant farmers in the cotton-growing North, timber workers in the Panhandle, trade unionists in and around Jacksonville — saw working-class solidarity as the lifeblood of freedom, and democracy in the factory and the fields as the solvent to petty tyrants.

DeSantis, the son of two Rust Belt parents, cites his working-class background when explaining the origins of his crusading, freedom-focused philosophy. Early in his new book, The Courage to be Free, DeSantis declares that he’s animated by “blue-collar values,” unlike the “entrenched elites” that come out of places like Yale and Harvard Law (his two alma maters). He spoke in a similar register at his second inaugural address this year, using the words “freedom” or “free” fourteen times and “liberty” four, dwarfing even his favorite bête noire, “woke” (three).

So what does freedom look like to DeSantis? A sort of pre–New Deal society with a weak welfare state, weak regulatory state, and, crucially, weak labor unions.

As a US representative from 2013 to 2018, DeSantis voted to axe Medicare and Social Security spending, applauded lifting the retirement age to seventy, and helped found the social spending–phobic House Freedom Caucus. As governor he has taken aim at Florida’s teachers unions, one of the few bastions of organized working-class power in a “right to work” state with just 4.5 percent of the workforce unionized. The Florida Legislature, at DeSantis’s urging, is currently considering legislation to make it easier to decertify public sector unions and harder to collect dues.

To DeSantis, freedom’s nemeses are “woke” media outlets, bureaucrats, and corporations — not because, say, companies constantly stomp on workers’ right to organize, but because some businesses now feel compelled to use anti-racist language. Likewise, being part of “the elite” doesn’t mean having a flush bank account or exercising direct control over workers’ livelihoods, but instead betraying a dash of social liberalism. As DeSantis writes in his latest book, Clarence Thomas is not a member of the ruling class, and “some who acquire great wealth, be it an oilman from Texas or an automobile dealer from Florida, are also part of the ‘outs’ because they do not subscribe to the prevailing outlook and philosophical preferences of the ruling class.”

One story from DeSantis’s book is illustrative. Working a summer job as an electrician’s assistant, DeSantis is sent home because he’s wearing “worn-out boots” that aren’t up to code. Rather than fault his employer for not supplying him with safe attire, DeSantis fumes about “the federal government’s regulatory Leviathan” — also known as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), an agency formed thanks to bottom-up pressure from the labor movement.

The Tampa cigar workers and their Florida Socialist Party brethren had a more realistic appraisal of who held power in society and who was a threat to the freedom of ordinary people. The state party dated its inception to a February 1900 speaking appearance by Eugene V. Debs, the most famous US Socialist of the day, in downtown Tampa. Debs thundered through a two-hour address on “Labor and Liberty” as the thousands-strong crowd, the Tampa Tribune reported, “filled all the available space in Courthouse square . . . and overflowed into courthouse windows, neighboring roofs and tree-tops.”

Florida Socialists won the most adherents in manufacturing-heavy Tampa and Jacksonville, but there were dozens of other branches scattered across the state. In the tiny northeast town of Hastings, black tenants and farmhands used the party local to set up a cooperative store in a bid to break the yoke of peonage. When the hamlet of Gulfport — across the bay from Tampa — incorporated in 1910, its mayor and four of five city councilors claimed Socialist Party membership and, rejecting the nostrum that private investors knew best, fashioned a democratic economic development that built up the city’s water works along with a Citizen’s Ice and Cold Storage.

But Tampa’s local was perhaps the most effervescent in the state, mixing seamlessly into the burbling elan of working-class neighborhoods like Ybor City. There, with cigar factories looming in the background, working-class clubs and cultural centers proliferated; political debates, speeches, and rallies rang out; prolabor newspapers of various languages and ideological stripes churned off the presses; and Socialists racked up impressive vote tallies. Italians, Spaniards, and Cubans and Afro-Cubans lived in close proximity and worked alongside each other in the cigar factories. Trolleys running through the neighborhood flouted Jim Crow laws.

The cigar workers, classic artisans, were the beau ideal of the community. They set their own hours, drank café con leche on the job, and even cut the workday short if there was a neighborhood baseball game. Interviewed decades later, one former cigar worker and Italian immigrant glowed: “I did love it because I had plenty of freedom. . . . If there was a ball game, I quit and go.”

The cigar workers struck repeatedly in those early decades of the 1900s, jostling for democracy on the factory floor. They fought for uniform wages across factories, resisted employer attempts to crush their unions, and, of course, battled to retain their beloved lector. Factory owners, in tones that Ron DeSantis could surely appreciate, angrily insisted on their right to govern the workplace as they wished, free from the collective meddling of workers.

The electoral highwater mark of Florida’s Socialist Party came in 1912, when Eugene Debs placed second in the state in the presidential race, besting both Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. World War I–era repression tore the party apart, and routed strikes spelled the end of the cigar workers’ cherished freedoms. In the 1920s and ’30s, the final lector platforms — the “advanced pulpits of liberty,” in Jose Marti’s memorable description — were razed. The business owners had won.

Ron DeSantis, too, is winning today. Eager to “make America Florida,” he’s all but certain to run for president while flying the freedom flag. But in a political and economic system where workers hold vanishingly little power, his is less an anti-plutocratic agenda than a platform of plucking out disfavored elites and plopping in traditionalist ones.

The Tampa cigar workers might have asked in response: What kind of freedom and for whom? The labor liberty of the lector and the organized worker, or the union-busting freedom of the factory owner? Working-class solidarity, or DeSantis’s hollow populism?