From Recovery to Union Renewal

What happens to worker power when the most pressing struggle in workers’ lives isn't against the boss but against addiction?

Used syringes at a needle exchange clinic on February 6, 2014 in St. Johnsbury, Vermont. Spencer Platt / Getty

Labor movements emerge from class conditions. This seems easy enough to accept but too general to provide solutions to US labor’s problems. If we turn to history, it would be hard to argue that major advances or retreats were caused by just one factor — be it economic, political, or organizational — rather than many. Most important labor histories, from E.P. Thompson’s Making of the English Working Class to Jefferson Cowie’s Stayin’ Alive, center on the idea of multiple causality, or what Louis Althusser called “overdetermination.” These authors drill down beneath quantitative indices of social change to the qualitative dimensions of everyday life. They find — again and again — that cultural practices, such as “blue Monday” among nineteenth-century craftsmen, or “disco sucks” events in the 1970s, helped accelerate or inhibit working-class action.

So far, however, most of our contemporary thinking on union decline and renewal has sidestepped this question (with notable exceptions, like the work of Paul Buhle). We focus heavily on unions’ internal structures and organizing strategies while integrating accounts of political economy, labor law, and worker demographics. A common, unstated assumption is that if only the right organizing model, legislative reform, or economic conjuncture presented itself, workers would burst forth in a new wave of membership and militancy. What is left unexamined are the ways precarious employment and the rise of a host of substitute activities have reshaped workers’ practices, identities, and their willingness to take collective action.

In 2015, I went to Woonsocket, Rhode Island, with these questions in mind. It was a storied center of textile production in the early twentieth century and of militant, social-democratic unionism in the 1930s and 1940s. But it had fallen on hard times, suffering the ravages of deindustrialization and failed attempts at renewal, though over a longer time frame than Flint or Detroit.

My visit was not purely academic. During my teens, I had lived in a neighboring town where people looked down on Woonsocket. Earlier, growing up near Lowell, Massachusetts, I spent almost every school trip touring its textile museum’s sanitized version of mill life. And before that, my grandfather and his generation had worked in Rhode Island mills. Though decades removed, his family’s culture still bears the marks of hardship, solidarity, and relative gender equality imprinted by that first wave of industrial capitalism.

When I walked Woonsocket’s largely empty Main Street with its iconic “Bienvenu” sign and scattered former factories, therefore, it was with more than a detached analytic gaze. I spoke with many residents — sixty, so far — and asked them about things I knew: work, wages, unions, politics. Everyone had something to say.

Artie, a forty-eight-year-old out-of-work carpenter told me, “These are hard times, bro. I’ve probably built a million houses, I’ve been a productive part of society, and for what? Some fucking asshole up in Boca Raton?”

Theresa, a forty-two-year-old single mother who had escaped an abusive relationship only to find a cold shoulder on the job market relayed her experience: “I filled out an application and they weren’t hiring anybody who didn’t have a college degree. They wanted people who are ‘future-oriented,’ they don’t want riff-raffs.’’

And Amanda, a mom in her twenties who had moved from Massachusetts for the cheap rent, recounted similar struggles applying for aid: “They denied me every single time saying that I make too much money. But when I open my fridge, I have no milk — like, I can’t afford to get it. I feel like I am always stuck under something. I’m stuck under the things that I can’t have.”

Deprivation was not hard to find. Nor were expressions of resistance and favorable views of unions. But beneath economics lay a deeper source of suffering that I was ill-equipped to understand. It provided both joy and pain in ever-shifting doses, and though more private in practice than union or political activism, it had clear social dimensions. I am speaking, of course, of opioid addiction.

Artie, who came from a “drug addict family” and said, “I do drugs and smoke weed,” was also adamant that “I’m not a heroin head; I’m not a fucking junkie.”

Theresa, who was on methadone when we spoke, found that heroin “helped me do what I’ve got to do. It gets me get through the day. If I could afford it, I would still be doing it.”

And as Kevin, a twenty-nine-year-old former convict and meat-packer explained it: “A few of my friends passed away this year because of the dope. Everybody is doing it — everybody. It’s the culture.”

Drug use and abuse were pervasive in the lives of Woonsocketers — their own, their friends’, their families’. It was a practice more immediate than wage exploitation and the struggle against it more salient than that against employers or the state.

At the level of culture, where identity is formed socially through channeling desire, substance dependence seemed to have replaced wage dependence, and recovery to have replaced unionism. This dynamic, buttressed by the confluence of union decline and overdose death at the national level, confounds most approaches to union renewal. It suggests that workers’ loss of power is no longer simply a deficiency to be corrected, but a problem that has bred its own answers. Responding to these answers in a way that overcomes shame while tapping the moral energy of recovery should be a central task of union activists.

Figure 1: Union Decline and Overdose Death Rates in the US, 1973–2016

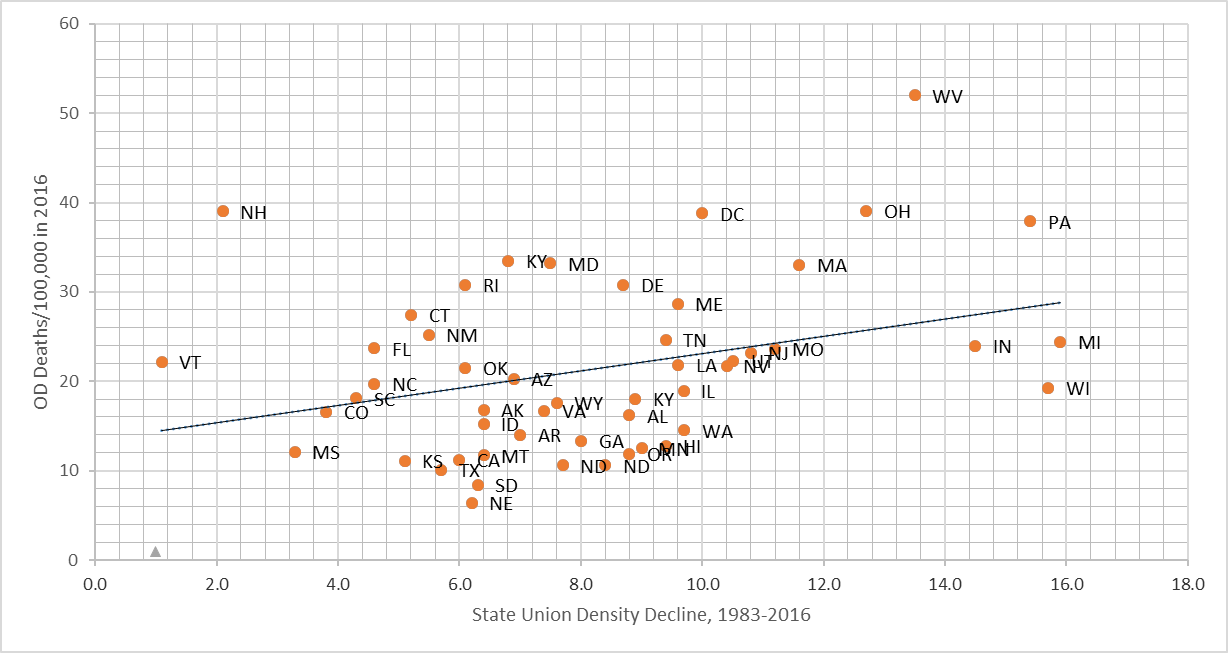

Figure 2: Union Decline (1983–2016) and Overdose Death Rate (2016) by US State

Sources: Hirsch and Macpherson 2018; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2017.

Precarious Work, Distant Unions

When one thinks of New England labor, Woonsocket doesn’t usually come to mind. Places like Lawrence, Lowell, or Fall River might come first, followed by Manchester, Worcester, or Providence. Indeed, Woonsocket is diminutive compared to these peers: its population peak of 50,000 in 1950 was less than half of theirs.

But its primary industry — woolen and worsted textiles — had a longer, skill-dependent shelf-life than cotton-centered production. While those better-known cities’ labor movements were hobbled by the early flight of cotton in the 1920s and experienced the 1934 textile strike as a rearguard defeat, for Woonsocket it inaugurated an impressive rise of worker power under the Independent Textile Union (ITU).

The wolf finally came for woolen and worsted too, as employers headed south in the 1950s. But the intervening years allowed Woonsocket’s mostly French-Canadian working class to take part in the CIO upsurge and taste its material gains.

“[T]hese workers,” argues Gary Gerstle in his seminal history, “made the city … into what Fall River and then Lawrence had once been — the bastion of organized labor in New England.”

Under the leadership of Franco-Belgian socialist Joseph Schmetz and American-born Lawrence Spitz, the ITU organized 84 percent of Woonsocket’s workforce, achieved record wage gains, and sought to wrest control of daily life from employers and the clergy with an ambitious cultural program that Gerstle calls “working-class Americanism.” Though delayed by ethnic insularity and church-enforced piety, class, in something close to its Marxian form, happened in Woonsocket.

And class has continued to happen there, in ways less liberating. Unions have largely evaporated and work, for many, has become intermittent and low-wage. Jobs were something subjects endured and were compelled to constantly seek but were not a stable source of bonding or identity. Even more so unions: none were current members and only a handful had ever been, though many had relatives who were.

The unifying experience of work, once central to the formation of union consciousness, was broken if not absent entirely.

April’s history was illustrative. “I dropped out in ninth grade,” she told me, “and from there I’ve done all kinds of small tedious jobs like babysitting, mostly retail and customer service. That pretty much sums it up, that’s my life. Most of it has always been short term.”

I then asked if she’d had any experience with unions: “No, I don’t know anything about them,” she replied, “I don’t like the unions where you pay dues and stuff. I thought about working at Stop n’ Shop because there’s a union but I don’t understand it, so I don’t want to put myself in a situation that could make things worse.”

Dan had a longer and more checkered career than April. “I started off bouncing around different schools and not having much of a work history, just bouncing from one job to another,” he explained. I asked how his current search was going: “It’s not easy,” he said, “because it’s like a new digital age with the resumes, everything is all computer instead of paper applications. Nowadays there’s a lot of people who are working for less money, instead of for what they should — especially people that don’t have a college education.” Dan had no experience with unions and made no mention of them.

Fred had no such experience either, but wished he had. “I’d love to be part of a union, to know that I’m safe if something came up — that’s the kind of security I do not have.”

Fred had moved to Woonsocket from Worcester, Massachusetts with his pregnant girlfriend. Though under thirty, he had type II diabetes and no tertiary education.

“I was living in Worcester and I got a job offer down here for store cleaning.” Before that Fred had worked as a temp for Labor Ready. “At Labor Ready,” he explained, “they know they can replace you, so you will find some people that don’t treat you too good.”

Jeff had been in and out of jail for robbery and drug charges but had sworn off both after the birth of his daughter six years before. His record hobbled his job search, however.

“Sometimes you get that hard month,” he said, “sometimes you have an easy month. Not having steady work and only doing small-time jobs here and there — you get by but you’re still scraping, and scraping isn’t enough. I always have this feeling of impending doom.”

Attachment to the formal economy or even to a craft or occupation that could provide “ontological security” had declined considerably in post-industrial Woonsocket. A predictable result of deindustrialization, the subjective effects of this process have rarely been followed to their conclusion. Workers left behind by such shifts are not merely surplus: April, Dan, Fred, and Jeff are still exploited by capital on an as-needed basis, and their role as consumers is far from negligible, though supported more by public assistance and informal income than by formal earnings.

Yet when work is no longer dependable and its forms increasingly vary — customer service, construction, cab driving, you name it — it ceases to be a dependable site for effort expenditure and identity formation. Precarious workers find alternatives. Barry, Artie’s similarly jobless older brother, described his own experience:

I was always a hard worker, boom, boom, boom. If I took too long of a lunch break my motivation would start to go out the window. When I’m working my mind is also working but it’s kind of relaxing. When I’m sitting and I’m stagnant, my mind races, then I fall into a depression. I’ll say “to hell with it!”

I used to have a bad drinking problem and that’s what mainly got me into trouble. The guys that I hung around with they all used drugs, drank heavily, and partied hard … I burned years like that off my life. Now I’m forty-nine and it’s like “Damn, what the hell was I thinking?” And I find myself — I feel like, damn, I don’t what to think anymore.

From Precarity to Substance Abuse

Alongside fragmented work and absent union experience, subjects described, over and over, the continuity and immanence of substances. Many were not themselves addicts but all witnessed heavy, endemic use in their immediate surroundings.

As wage work had become unreliable for social bonding and libidinal output, seeking, consuming, and selling drugs had remained constant. Substance use appeared to replace work as the most unifying daily practice; resisting it appeared to replace unionism.

Corinne’s interaction began in childhood. “My parents are both junkies,” she told me. “They were good parents though, always emotionally there, just addiction gets annoying.” Corinne had dabbled in opioids herself: “I did heroin only a handful of times and I was like ‘this is stupid’ so I stopped.”

But she opined on the reasons for its use around her: “I think it’s a hard time,” she said, referring to the economy. “And it’s easy — people get depressed, it’s easy to grab a bottle or do heroin and just not think for a little awhile. That is why I did it.”

Sara, like Fred, had also moved to Woonsocket from Worcester. Herself a recovering addict who was now married and trying to live clean, she had moved to Woonsocket because she thought it would be better for her two kids. She was largely disappointed.

“When we lived in Worcester,” she explained, “it was like you would walk down the street and people would ask me if I was working [as a sex worker]; they would ask me if I wanted drugs. Now in Woonsocket I’ve tried to connect with people that I see have kids and I find out they do drugs with their kids — not with their kids, but they are home watching them and not really paying attention.”

Cami, however, had a different experience of Woonsocket. Born in Massachusetts to Puerto Rican parents, she had traversed much of southern New England in cycles of addiction. “I can’t even count how many times I was in rehab,” she told me, “how many times I’ve seen substance-use counsellors. But I finally surrendered and went into rehab November 2015. It changed my life in a really big way because I was able to stay clean.”

Since then she had moved to Woonsocket from Providence and found a supportive environment for recovery. “That’s something I love about Woonsocket,” she explained, “they have like this little system going on and people support each other and look out for each other. It’s really cool.”

Carl felt the same. A fifty-five-year-old man of Haitian descent who had been addicted for much of his life (though never to opioids) and was HIV-positive, he found Woonsocket to be a safe, “rural” haven for his recovery. As we spoke in the office of a local nonprofit where he was receiving job training, he explained to me his history:

I came to Rhode Island in the mid-nineties to better myself, to get an education and so forth, but I lived in Providence and got caught up in drugs. So I went into rehab and then moved to Woonsocket [four years ago] to get away from my family, who used alcohol or have a party mindset …. It has been very much helpful to live here in Woonsocket.

Carl had been sober for four years at that time, had regained housing after long bouts of homelessness, and was studying toward an associate’s degree. He credited his time in Woonsocket and the same nonprofit, which had also aided his recovery, with this turnaround.

These stories suggest two things. First, they display the depth and pervasiveness of substance abuse in general and opioid abuse in particular among key groups of contemporary workers. They show this in a way that is not simply parallel to other pursuits, such as work, family, or hobbies, but central and in many ways a replacement.

But second, and in response to such ubiquity, they display a reorientation of resistance toward their own habits and those of users around them. Either way, this struggle is internal: internal to the self among recovering addicts; internal to working-class communities among nonusers.

Class-based resistance, so clearly seen in the strikes and protest of Depression-era Woonsocket, has thus not entirely disappeared in the twenty-first century. It has in large part been redirected toward substances, the new agents of dependence, rather than employers.

From Recovery to Union Renewal?

One moral from this story might be that the rust-belt working class is too drugged or immersed in personal struggles to mount credible movements against capital, be they labor-based or otherwise. Without indulging in conspiracy theory, there is an established pattern of subaltern groups deemed “superfluous” by elites succumbing to mass addiction and hastening their own demise.

Such a pattern, if true of Woonsocket and similar places, might implicate at least a subgroup of workers in unknowingly serving the ends of capital, much as Paul Willis, in his 1977 ethnography Learning to Labor, found working-class “lads” reproducing themselves as manual laborers.

But such pessimism is not the only nor even the most convincing lesson. The energy and commitment many in Woonsocket put toward resisting or overcoming addiction both individually and collectively speaks for working-class agency over subjection.

In historical perspective, this can be seen as a displacement or desublimation of struggle against once-salient employers to now-salient drug use. The question for union activists is whether and how such energy could be (re)directed toward organizing.

Here, the West Virginia teachers’ strike is instructive. In 2016, West Virginia was by far worst hit by the opioid crisis — in Figure 2, its dot occupies the top rung, displaying an overdose death rate of 52 per 100,000. It also experienced one of the steepest declines in union density since the early 1980s, a sharp contrast to its long tradition of mine-worker unionism.

Yet in February 2018, teachers across the state launched one of the most successful mass strikes in recent history. Some, like one South Charleston high school teacher, directly referenced the degradation of addiction: “We’re feeling a cumulative effect of West Virginia’s bad economy. All the economic desperation in the state, the opioid crisis — kids bring that with them into the classroom …. There’s a feeling that the whole state is ready for a strike.”

To be sure, teachers occupy a more stable stratum and are less vulnerable to opioid abuse than the unemployed or semi-employed whose children they teach. But their collective efficacy and widespread support in addiction-addled West Virginia speak against complacency as the only possible outcome.

The task for union activists who seek to reinvigorate these communities will be to address these practices as they exist and forge links from class-internal recovery to class-external resistance. This might take the form of incorporating language from recovery programs in workplace-based organizing. More broadly, it might consist in community-based initiatives that provide collective support for addiction recovery (or avoidance) while pointing to its wider social causes and solutions. The latter extends well beyond traditional trade unionism but is not inconsistent with the holistic approach of many worker centers — a model which, despite limitations, unions have tried to learn from.

As preliminary as these lessons are, they suggest that job loss, union decline, and opioid addiction are bound by more than coincidence. Woonsocket’s story points to drugs as a conspicuous replacement for wage dependence and recovery as something similar for unionism. It reminds us that there are deeper registers to working-class life than the higher frequencies of wages, conditions, and NLRB elections. To those who would bypass the messiness of culture in pursuit of these more tangible “deliverables” the answer is simply: it ain’t like that.