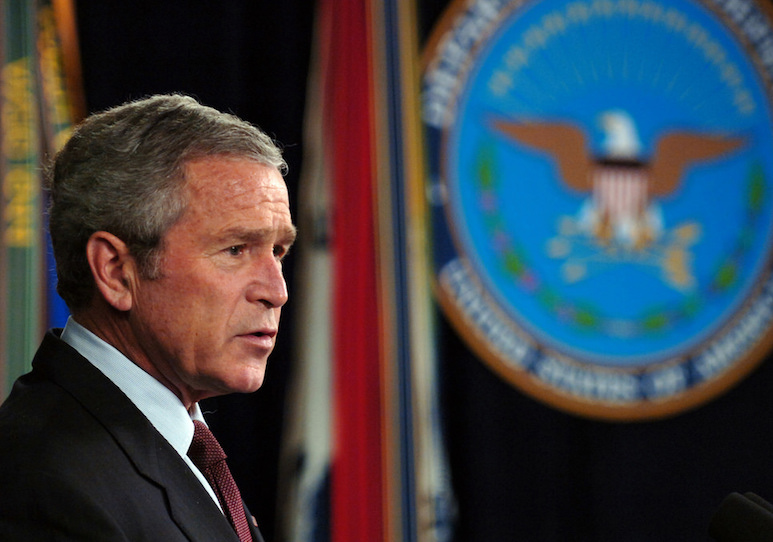

When W. Was President

The George W. Bush years were pretty bleak. The political possibilities for pushing back are much more promising today.

George W. Bush speaks to reporters at the Pentagon in January 2006. Helene C. Stikkel / Department of Defense

In the mid-2000s, I co-ran an organization called Against the War on Terror. It was about six of us in New York City, running a blog, holding teach-ins and public debates, arguing that it wasn’t enough to be against the War in Iraq or Gitmo — the only progressive position was to be against the “war on terror” itself.

That war was the real threat to liberty, not just because it was a smokescreen to push all kinds of racist persecution of Muslims and more over-policing of minorities, but because of the way it substituted the politics of fear for an actual politics of freedom. It made security the basic principle of politics, and turned the pursuit of absolute security into a war — unhinged not just from institutional restraints but also from the restraints of limiting principles, like liberty.

The only way to enjoy freedom, we said, was to accept insecurity as a cost, a welcome cost, of living together with others who were also free.

The thing I most remember about that moment is how closed the political environment was. We found a few allies (including Christian Parenti, Corey Robin, Stanley Aronowitz, and Doug Henwood), but on the whole, things were pretty quiet and fragmented outside of Iraq War politics. Democratic resistance to the war on terror was nonexistent. Liberals had signed up en masse; the main line of criticism was that Bush conducted the war on terror poorly, not that we shouldn’t be fighting it in the first place (what did it even mean to wage a war against terror?).

With the exception of the major antiwar protests — which achieved very little — it was very difficult to mount any kind of real protest politics.

The Bush-era “Muslim registration” program, which beginning in 2003 forced more than one hundred thousand foreign nationals from what eventually amounted to twenty-four Muslim-majority countries (and North Korea) to register in the US, and led to thousands of deportations, faced relatively little mass opposition. Nor did many of the administration’s other programs and positions — on refugees, asylums, torture, the 2006 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and so on. The ideological hegemony of that period — the broad-based mainstream consent and acquiescence to the war on terror — was sufficiently entrenched that opposition politics was weak and fragmented.

I’ve been thinking about that period, because in comparison, the present holds much more possibility. The Trump administration appears weak, and there’s noticeably more spontaneous resistance up and down the line, from the tepid to the more principled.

You have Republican senators publicly criticizing Trump; mayors of major cities coming out against the administration’s immigration policies; much less media acquiescence in official narratives and statements; liberal Democrats showing up at events organized by CAIR (which, though pretty moderate, used to be utterly radioactive simply because it represented Muslims); massive marches, on different policies, in consecutive weeks; and so on.

It’s not like revolution is around the corner. We’re still losing. The Democratic Party is weak and compromised, and the organizations to its left remain weak. The Republicans are still going to do a bunch of wretched stuff.

But we shouldn’t overstate just how strong and capable Trump and company are. They’re having more trouble, not less, than Bush. They’re more vulnerable, not less — and not just Trump. If the right political decisions are made, the GOP can be saddled with the albatross of Trump. And perhaps the Left can even start carving out a space independent of the Democratic Party.

It’s a better time to be doing any kind of leftist politics than it was a decade ago.