The Decline of the American Empire

Neoliberalism lives and shouldn't be given a premature obituary, but the American empire has entered a decadent phase.

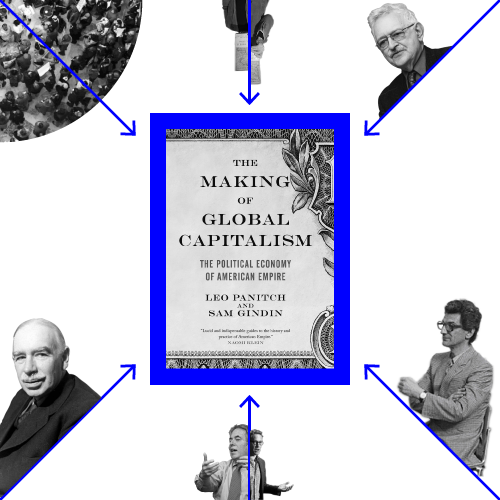

(Remeike Forbes / Jacobin)

These are comments delivered at a panel on The Making of Global Capitalism by Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin. Jacobin published a symposium on the volume earlier this year.

I want to start by saying that I greatly admire this book, and pretty much everything these two guys have done over the years. Unusually for the genre, I meant every word of the blurb I supplied for it. A while back, I was on a panel with Radikha Desai, on which she argued that the US empire was not really much of a success compared to its British predecessor, which made me wonder what planet she’d been living on. (Given the stars of this panel, it can’t be her residence in Canada that led to this strange conclusion.) The thing has been incredibly successful on its own terms, and Leo and Sam are excellent at pointing out some of the mechanisms of its success, like the skillful incorporation of the second tier powers like Western Europe and Japan (I could say Canada as well, but it’s something of a special case). They have a high standard of living, and can even ride a moral high horse now and then while the US military does the dirty work of imperial policing. Of course, life in the third and fourth tiers of the empire is another story — one of debt and profit extraction and the occasional CIA-sponsored coup.

And the ability of the US planning elite to transcend immediate national interests to promote the health of the global system has been extremely impressive. Just to pick one example of something I found profoundly clarifying, I never really understood US strategy around Middle Eastern oil. Noam Chomsky likes to quote a 1940s planning document on what a strategic prize control of that oil is, but once the producing countries nationalized that oil in the 1970s, it didn’t seem like the US derived any great economic or strategic advantage from its influence and power in the region. After all, we produce far more hydrocarbons domestically than most of the second tier countries, and our immediate neighbors produce plenty as well. Leo and Sam offer a much more satisfying explanation: the US interest is in the free flow of oil for the health of the global system.

And then there was support for the rebuilding of Japan and Europe after World War II — and in more recent decades, the encouragement of European unification. Narrow self-interest would have viewed these actions as the nurturing of potential competitors to US business — and it’s turned out that way, they are. But again, the health of the global system demanded it, and the planners rose to the occasion.

Of course, I had to come to the “but” part of this little commentary, and here it is. You may have noticed that at the beginning I said the US empire “has been” very successful on its own terms. And I said the planners “rose” to the occasion. The choice of verb tenses gives a clue to where I’m going: are the best days of the American empire behind us? I’m phrasing this as a question because I’m not fully sure of the answer. The claim was made without a question mark in the 1970s and 1980s, and ended up looking foolish in the 1990s. More recently, a lot of analysts used the financial crisis of 2008 — it’s a little hard to believe that Lehman Bros. collapsed five years ago, and, as Martin Wolf pointed out in the Financial Times the other day, we still live in Lehman’s shadow, making it at once old news and a current event — to pronounce the death of neoliberalism, but the thing soldiers on. Enormous state resources were successfully mobilized to keep the banks not merely afloat, but dominant. Neoliberalism lives, at least for now. One should be on guard against publishing premature obituaries, both for empires and regimes of accumulation.

But I do want to list some reasons why I think the empire has entered a decadent phase. A couple of years ago, word reached Leo that I’d given a talk in Ottawa that sounded declininst, and he was alarmed. Until then, we’d seen pretty much eye to eye on the incorrectness of the declinist line, and he was concerned that I was embracing unsound doctrine. Sorry, Leo, I’m going to be unsound for a bit.

Several things strike me as signs of rather profound rot. Let’s start with the narrowly economic — specifically investment.

(If I had time I could talk about the rise in US foreign debt, a trend that survived the Great Recession. Some argue that the continue ability of the US to sell its debt is a sign of strength — which it is, until someday, foreigners decide not to buy any more, and then it isn’t anymore. Remember that Alan Greenspan said during the housing bubble that there was no reason to worry because things were going well so far. But back to investment.)

US corporations are highly profitable and flush with cash. At last count (Z,1 Release) , US nonfinancial corporations had nearly $16 trillion in financial assets on their balance sheets, almost as much as they have in tangible assets. The gap between internal funds available for investment and actual capital expenditures — what’s called free cash flow — is very wide at around 2% of GDP. That’s down from the high of 3% set a couple of years ago, but still higher than at any point before 2005. Instead of investing — and remember, profitability is quite high — corporations are shoveling cash out to their shareholders. Through takeovers, buybacks, and traditional dividends, nonfinancial corporations are transferring an amount equal to 5% of GDP to their shareholders these days — again, down some from recent highs, but very high by historical standards. This reflects the victory of the shareholder revolution, a crucial component of the neoliberal era of the last three decades, which established the fact that making shareholders happy is the principal reason for a public corporation’s existence. And that happiness is measured over the very short term: more money, now. The future, well, we can worry about that some other time. Alfred Marshall famously defined interest as the reward for waiting, but American capital has lost all patience (not that interest rates these days offer much of a reward).

The lack of interest in investing for the long term is visible in the national income accounts as well as corporate accounts. What matters for the accumulation of real capital is net investment — the gross amount invested every year less the depreciation of the existing capital stock. We’ve just gotten numbers for 2012, and they’re remarkably low. (See tables 5.2.5 and 5.2.6 here.) Private sector net nonresidential fixed investment (as a percent of net domestic product, or NDP) fell below 1% in 2009. It’s recovered some, to just over 2% last year, but that’s half the 1950–2000 average, and lower than any year between 1945 and 2009. We won’t have 2013 numbers until August of next year, but it’s looking like they’ll stay in this depressed neighborhood. Two things are responsible for this: low levels of gross investment to start with, and a skew of investment towards short-lived, quick return goods.

Public investment is even weaker. Net investment by all levels of government was just under 1% of NDP in 2012, the lowest since 1949 (following the postwar demobilization). Federal net investment was very close to 0% of NDP. Though state and local net investment was positive, but at the lowest level it’s been since the late 1940s.

When measured in real dollars, the trajectory of net investment has to be described as a collapse from which we’ve barely recovered. Net domestic fixed investment of all kinds in 2012 was 54% below its 2005 peak. Public investment was down 43% from its 2004 peak. Residential investment was down 89% from its 2005 peak. Private nonresidential fixed investment was 32% below its 2008 peak. In most cases, real net investment is at late 1970s/early 1980s levels — that, even though real GDP has more than doubled over the last three decades.

I suppose we could talk for hours about the differences and commonalities between an owning class and a ruling class, but what this net investment story tells me is that we have an elite interested in nothing other than short-term enrichment. At that, it’s been very successful. As we learned the other day, 95% of the growth in income between the end of the recession in 2009 and last year went to the richest 1% of the population. But it looks like it’s taking the money and running. It doesn’t seem to have much faith in the future.

Which takes me to the political, and then the psychological, sphere. It is amazing to watch the US Congress seriously flirt with defaulting on Treasury debt. It makes you have to rethink everything you thought about capitalist power and the state. I doubt they’ll actually default — there will be some last second deal to raise the debt ceiling, temporarily, but we’ll probably be back here again soon. It’s something of a mystery to me whom the current Republican party represents — surely it’s not classical Wall Street interests, because they wouldn’t be playing chicken with the status of Treasury bonds. But those Wall Street interests, and their friends in the Fortune 500, don’t seem to be sitting the back-benchers down for a lecture on their class duty. (Or if they are, the back-benchers aren’t listening.) The contrast with the planning elite that came out of World War II that Leo and Sam write about is stark.

And now onto the psychological realm. I’ve been thinking lately about what we might call the neoliberal self. Gone seems to be the classically bourgeois executive ego, a relatively stable, if sometimes anal-retentive structure to guide the subject through life. In its place is a much more fragmented thing, adaptable to a world of unstable employment and volatile financial markets — but unable to think seriously about long-term things like social cohesion or, god save us, climate change.

The material basis of this transformation looks to be the replacement of the relationship by the transaction, to steal the language of corporate governance. Workers are told to run their lives like little entrepreneurs, moving from one ill-paying short-term job to another, or maybe holding two or three at a time. And at the top of the society, we see the erosion of the planning function, and any rationality beyond the most crudely instrumental. It’s been a long time since I read Polanyi, but this seems to me a perspective on the social rot produced by market-regulated societies, from the macro level of investment down to the socially shaped psychology of how we think and feel. I don’t see how the imperium can long survive this sort of pervasive rot.