How the Democratic Party Was Hollowed Out

Democrats appear incapable of mounting a real opposition to Donald Trump. Their weakness is the result of a decades-long hollowing out of the party, in which organized labor has been displaced by a panoply of interest groups and nonprofit organizations.

The Democratic Party’s transformation into a network of policy clientele organizations has left it incapacitated as an opposition party. (Tasos Katopodis / Getty Images)

The first few weeks of Donald Trump’s second presidential term began — as did so many events that defined his first four years in office — with a nationwide search for categories. How best to describe the mass firings of civil servants, the impoundment of billions in congressionally appropriated funds, the disappearances and arbitrary detentions, and the refusals to abide by court injunctions on these maneuvers? A coup or a constitutional crisis? A pushing of the office’s boundaries or a rupture of the separation of powers? Questions like these haunted the pages of the Washington Post and Foreign Affairs and interviews on public radio, to say nothing of the listservs of legal scholars. These were, by this point, quite familiar lines of inquiry. They would not have been out of place in the voluminous pop social science and history titles that materialized on the shelves of airport bookstores to process Trump’s first term, books with stark monochromatic covers and titles like How Democracies Die.

If the questions were echoes of the past, the reality they aimed to classify was not. The first few months of 2017 were characterized by chaotic but ultimately halting attempts of an administration not quite ready to step into the void of power. The weeks that followed Trump’s second inauguration revealed an administration with a semblance of a playbook for seizing the state — articulated by presidential transition teams like the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 blueprint. The plans brought with them a more coherent cadre of leaders vetted by Trump’s political operation, in contrast to the motley gang of Republican functionaries who surrounded the president in 2017. At the center of these operations was the richest man in the world, Elon Musk, who had (until his messy breakup with the president) been allowed unfettered access to the technical interface of federal agencies — including access to payment and personnel management systems. These differences were reinforced by a new legal climate; in its decision in Trump v. United States (2024), the Supreme Court had extended the doctrine of presidential immunity to all of a president’s official acts. If the boundaries on the executive were a series of doors pretending to be walls, they were open. By late February, it was hardly out of place for Trump to write on his personal X and Truth Social accounts that “he who saves his Country does not violate any Law.”

Perhaps no difference was quite as stark as the initial absence of a visible political opposition. Leaders of the Democratic Party appeared incapable of metabolizing the assault on the political arena that was to come. House minority leader Hakeem Jeffries summed up the party’s early “play dead” strategic posture in a February press briefing: “What leverage do we have? Republicans have repeatedly lectured America — they control the House, the Senate, and the presidency. It’s their government.” In the ensuing months, public protest actions have ramped up somewhat, as federal employees have been sacked by the tens of thousands, hundreds of billions in federal grants were terminated, and noncitizens were disappeared to ICE detention facilities or, worse, a gulag in El Salvador. Still, even if the second coming of the Trump “resistance” has managed to surpass the scale of the first, its impact is blunted by the absence of an initial focal-point march of the sort that brought five hundred thousand persons to Washington, DC, in January of 2017. Even when millions of Americans do turn out at nationwide protests, as they did in early April 2025, newspapers around the country bury protest actions on back pages. In any case, the most visible and impactful forms of opposition have not come from the opposition party itself.

Yet if Democrats have proved reluctant to take up the role of loyal opposition, it is not — as liberal pundits had feared — a reflection of the so-called normalization of Trump, much less public approbation for his approach to governance or the consolidation of a new Republican majority. Nor is it merely the case — as the party’s critics have alleged since at least the last decade of the twentieth century — that Democrats and their allies in the liberal commentariat have simply lost the talent for telling stories that resonate with working-class voters rather than consultants and professors. While party leaders do appear allergic to political formulas that involve anything that could be labeled as populist — witness the marginalization of Tim Walz during the 2024 campaign — weak PR is better understood as a symptom.

Among other things, weak PR is symptomatic of a political party structure that has become, in the words of Daniel Schlozman and Sam Rosenfeld, hollowed out in recent decades — incapable of controlling key functions like candidate selection, fundraising, and the formation of policy, which are increasingly delegated to a network of outside groups, the media, and wealthy donors. Although hollowing is the dominant pattern in the party systems of wealthy democracies, it has manifested in highly divergent ways. For its part, the Republican Party has become — at both the elite and mass levels — a network of ideological movement organizations oriented around an amorphous set of ideological principles ranging from a radical retrenchment of redistributive spending and an increasingly exclusionary position on immigration to the preservation of traditional values and family structures. Democrats’ hollowing, by contrast, has involved the displacement of organized labor by an increasingly dense field of interest groups and nonprofit organizations. The common link between these groups is not their commitment to a set of ideological principles or identities but their attachment to public programs. The nature of these programs varies widely, and includes major social expenditures (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid), rights regimes (the Voting Rights Act), and a host of distributive programs ranging from Community Development Block Grants to National Science Foundation awards.

It stands to reason that the Democratic Party — once hollowed out — should take the form of a loose network of policy clientele groups rather than committed ideologues. In the long run, not only did Progressive Era reforms like the merit system and the secret ballot short-circuit local systems of patronage and weaken the power of party leaders; the New Deal provided a vast array of new social services that were largely insulated from the control of party machines. As the state absorbed these traditional party functions, so too did it advantage relatively new forms of organization — pressure groups, lobbies, social welfare organizations — in making claims on government. The fragmentation of the political landscape continued apace as the federal government’s investment in social programs grew during the Great Society, which both triggered the formation of policy-focused interest groups and poured federal resources into nonprofit organizations, which became critical conduits of welfare service provision. By the early 1970s, Congress had also begun to construct a “litigation state,” which incentivized private lawsuits as a means of enforcing new federal regulations on everything from civil rights to environmental protections. This transformation further fragmented power by spurring the creation of a large number of public-interest legal organizations that pushed political conflict into the legal domain. The organizational substructure of the Democratic Party was now a loose assemblage of policy experts, lawyers, and advocacy organizations.

Officially, these groups had allegiances to the beneficiaries of the programs that were their raison d’être — and not to political parties. Yet Democrats’ firm control over the legislative branch during the ascendence of what political scientists Karen Orren and Stephen Skowronek call the “policy state” made it the de facto party of the policy clientele groups — an increasingly large tent that eventually grew to encompass everything from identity-based organizations to high finance. The Reagan revolution and its assault on the central ideas and political alignments of the New Deal regime flung these clientele groups ever more firmly into Democrats’ arms.

But the partnership has yielded little in the way of either political stability for Democrats or policy gains for the “stakeholders” whom the clientele groups claimed to represent. For their part, as the political scientists Dan Galvin and Chloe Thurston argue, Democrats have come to treat policymaking as a substitute for party building. Yet programs — especially of the technocratic, market-oriented variant that attract the affection of the party’s intelligentsia — do not make for durable electoral alliances. If anything, the Democrats’ late programmatic style has only further severed the links between party, state, and mass electorate.

Perhaps more important, policy clientele groups are poorly situated to either articulate broad public demands or to engage in collective action to secure them. Not only do they lack the structural power of labor or capital; they also lack the mass-membership bases necessary to bargain with elected officials within the Democratic Party. When confronting political conflicts, they are more apt to seek out piecemeal victories or to preserve existing gains rather than expand the political horizon. That these organizations, even when they have dues-paying members, are rarely constituted as member democracies further limits both their incentives and capacities for engaging in sustained political conflict. They are built to preserve the legislative status quo ante. When this proves impossible, they will find themselves at an impasse.

And so while the Trump administration’s assault on the administrative state is likely to strike at the rights and benefits policy clientele groups cherish, these organizations have found it difficult to organize a tenacious counteroffensive that extends beyond the courts. Even if they are successful at litigation, assuming the Trump administration does not simply ignore court orders, this provides Democrats with few incentives to reshape their agenda. Uniting the far-flung and fragmented constituencies affected by Trump’s assault on democracy will depend in part on whether Democrats can be moved to transcend the politics of programmatic liberalism and embrace an alternative political formula. This formula should be built on centering appeals on the material concerns of the working class and generating solidarity through organizational work at the smallest units of political geography.

The Old New Politics

On a frosty day in January 1995, Ted Kennedy — then beginning his sixth term as the “lion” of the US Senate — was speaking at a lunch at the National Press Club, and he was on the warpath. His party had just suffered severe losses in the 1994 midterm elections, and its leadership, now under the helm of the conservative New Democrats (a group that included President Bill Clinton), was preparing to tack further to the right. Kennedy would have none of it. Liberals enjoyed wide public support on issues like universal health care, cash benefits for the poor, and the issues that mattered to working families in Massachusetts towns like New Bedford and Fall River. If Democrats ran for cover, “sheepishly acquiescing” to Republican caricatures of their values, they would lose, and would deserve to lose. “The last thing this country needs is two Republican parties,” Kennedy said. He would lose this battle for the soul of this party, as Democrats would play a leading role in the assault on anti-poverty programs and the growing privatization of much of the welfare state.

Afoot here was something more than an ideological battle between the last vestiges of the New Deal coalition and the neoliberals gaining ground in center-left parties in rich democracies around the world. Rather, the Democrats had been organizationally hollowed out. In the decades that led up to their loss in the 1994 midterms, Democrats — via a combination of institutional reforms and ruptures in the New Deal coalition — could no longer play a leading role in organizing democracy. Following changes in nomination procedures and campaign finance laws, the party effectively delegated candidate recruitment and campaigning to well-heeled outside organizations. Policy planning was now the object of an increasingly dense network of think tanks and narrow, memberless interest groups. This rendered the party not only an increasingly marginal presence in voters’ lives but incapable of solving coordination problems and setting a broadly appealing public agenda. That Kennedy’s causes enjoyed wide public support while his party did not was thus one foreseeable outcome of these changes.

Still, hollowness was not the only distinguishing characteristic the Democratic Party acquired during the closing decades of the twentieth century. As the New Deal’s loosely patched-together coalition of Northern white-ethnic urban political machines, labor unions, and Jim Crow enclaves gave way, the party attracted a booming base of educated and increasingly affluent professional-class liberals. These were quite literally the children of the same postwar labor-market institutions, housing policies, and arrangements for the financing of higher education that had given birth to the sprawling suburbs in which they dwelled.

If professional-class liberals left a stamp on the Democratic Party — both as an electoral base and a leadership cadre — their legacy has been a highly contradictory one. In recent decades, public opinion has reflected an enduring proclivity toward operational liberalism, with broad swaths of the population supporting policies ranging from universal health insurance to universal prekindergarten programs. Nevertheless, liberalism itself — as social identity and public philosophy — has become increasingly associated with an admixture of paternalistic tone-policing and technocratic or economistic policy fixes that fail to deliver on lofty promises of shared prosperity. The 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is a perfect embodiment of these policies. Despite resulting in significant gains in health insurance coverage for nearly nineteen million Americans, the policy’s infrastructure hinged on a combination of clunky, opaque market mechanisms and means-tested programs that were difficult for consumers to navigate. The program’s individual-market reforms also initially relied on a tax incentive that, rather than providing the uninsured with a generous state source of insurance, imposed a penalty for those who did not purchase private coverage — a working example of neoliberal paternalism. Little wonder that the program’s approval rating failed to crest 50 percent until Republicans threatened legislative repeal in 2017.

At the helm of the Democratic coalition, professional-class liberals can be counted on to design programs that bury popular benefits in a web of complex tax credits and public-private partnerships, awash in abstruse policy concepts that few voters — even reliable party supporters — can recognize. But these critiques of technocratic thinking could just as easily be applied to the consultant class of the Clinton and Obama administrations as they could to the more patrician architects of the New Deal. The difference of course is that professional-class liberals have — whether knowingly or not — shed even the pretense of reforming capitalism that their ancestors maintained. In a pair of bracing histories of the party, Lily Geismer has illustrated that the managers and policy wonks who increasingly dominated the upper ranks of Democratic leadership have retooled New Deal commitments to address poverty and material insecurity as instruments for labor discipline and capital accumulation.

Yet as Geismer ably demonstrates, if the Democratic Party’s transformation did not happen from the top down, nor did it simply emerge from the bottom up. It was instead a transformation of the meso-level, one rooted in a vast coalition of professional organizations that came to define the Democratic Party’s coalition — both as intense demanders of public policy and as a training ground for the party’s future elected officials, fundraisers, and top managers. These organizations were at the core of what came to be known, in the parlance of 1970s political science, as the New Politics. Narrow, issue-specific activist organizations supporting environmental regulations, consumer protections, and social justice not only upended the old politics of party-driven brokerage; they hauled in new, postmaterialist concerns — the province of professional-class voters and issue activists. In place of the quiet, transactional bargaining of prior decades, these organizations injected a new serum of moralism into the public sphere. This tone was communicated not through interactions on doorsteps or at factory gates but via new technologies of direct mail, polling, and, within a few short years, cable television. At the mass level, smaller but more informed “issue publics” became the target of political communication, while large swaths of the party faithful could be enrolled as consumer-members of groups like the Sierra Club, the National Association of Rail Passengers, or the National Low-Income Housing Coalition.

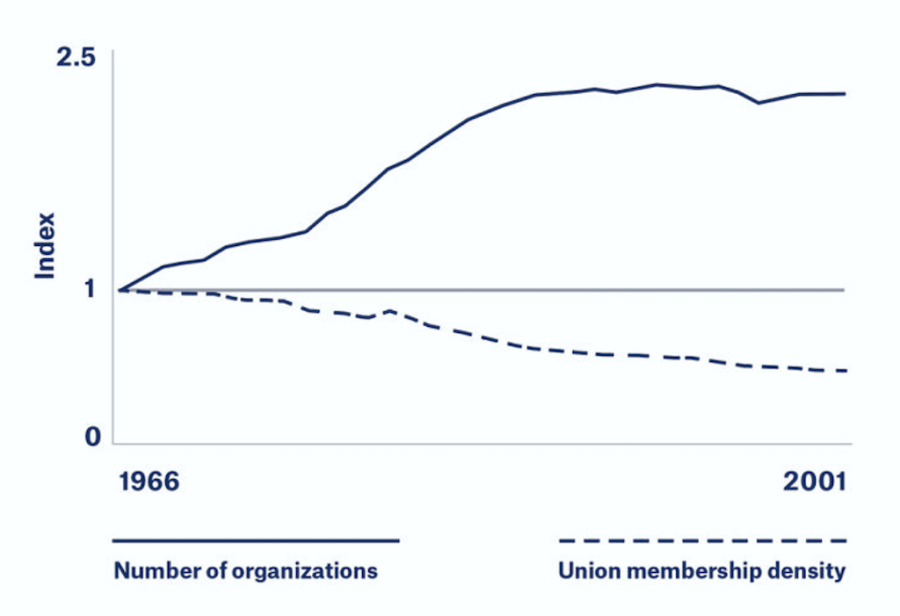

The two major parties, however, attracted two different kinds of issue networks. Whereas Democrats assembled a fragmented assemblage of group-based interests, Republicans’ organizational coalition was built around a more coherent set of ideological groups whose stated goal was to limit the scope of the federal government. This asymmetry has much to do with the policies Democrats themselves had created. To understand why, it is helpful to trace how these groups emerged in the first place. During the early postwar years, American politics was defined by a relatively limited and stable interest-group system, dominated by peak business groups and trade associations. The ratio of profit to nonprofit groups established in Washington, DC, was three to one. Yet by the 1960s, a growing number of social movements, activist networks, and policy professionals coalesced to produce a landmark series of policy changes — what the political scientist Bryan Jones and his collaborators call a “great broadening” of government’s role in American life. The expansion of government programs underwrote an explosion in the number of organized groups. For the first decade of the broadening, the thickening of the interest-group system was defined by policy clientele organizations in the mold of AARP but on a far smaller scale (see the solid line in graph below).

Capital’s agents in Washington — initially caught flat-footed by these developments — soon caught up. Between 1975 and 1985, the number of organizations representing the finance and domestic commerce sector increased by a third. These organizations soon proved far more effective in the political arena. Between 1998 and 2012, the ratio of business lobbying expenditures to the expenditures of diffuse interest groups and labor unions increased by two-thirds.

These changes in the system of organized interests were mirrored by a decay in union density, the most reliable indicator of working-class power (see figure 1). Union membership declined from 24 percent of wage and salary workers in 1973 to just above 10 percent in 2023. The imprint of this change on the political arena was significant. Between 1969 and 1982, the AFL-CIO received the most TV news coverage of any group or association in American politics, and the United Auto Workers was sixth. Neither was in the top twenty in 1995, nor was any labor union, save the Major League Baseball Players Association. While union members number in the millions today, the national political arena is increasingly dominated not by labor coalitions but by organizations speaking on behalf of narrow slices of policy beneficiaries. Of these, only a small handful have a mass-membership base. Even where they do exist, these membership bases are largely treated as passive donors or consumers rather than participants in political struggle.

Labor was an enduringly important part of the Democratic coalition through the early decades of the twenty-first century. Yet union leaders confronted a newly fragmented bargaining environment where it was far easier for other groups in the party’s coalition to develop greater independence, preventing labor from playing a central role in interest aggregation. In this context, labor struggled to build congressional majorities to support far-reaching social programs, to say nothing of legal changes to shore up labor’s vulnerabilities. As labor’s disruptive capacity waned, the Democrats now faced the challenge of brokering a coalition whose member organizations had few points of intersection with one another, limited ties to large swaths of the electorate, and, perhaps most important, no access to sources of structural power.

Lineages of the Policy State

That Democrats have become the party of the policy clientele organizations has not, all things considered, attracted much notice as a source of political vulnerability. In fact, the explosion of groups that have grown in the shadow of the policy state is more routinely cited as evidence of the party’s political successes. Among political scientists it has become an article of faith that policies have the potential to remake politics. Arguably the first to articulate this formula was E. E. Schattschneider, whose 1935 book, Politics, Pressures, and the Tariff, illustrated how protectionist policies helped to grow the industries that became its “fighting legions” when tariffs came under attack. Policies could just as easily destroy interests, Schattschneider wrote: “The losers adapt themselves to the new conditions imposed upon them, find themselves without the means to continue the struggle, or become discouraged and go out of business.”

This insight has had profound implications for theories of economic democracy. If a national pension plan creates its own powerful support constituencies, its existence will no longer depend on the labor unions, social movement organizations, and left parties that created it in the first place. Thus, as Paul Pierson was later to show in his seminal Dismantling the Welfare State?, even as “left power resources” — unions and electorally formidable mass-membership left parties — were depleted in the latter decades of the twentieth century, the social programs that left parties had helped to create stood firm in the face of neoliberal governments’ efforts to destroy them. Less than a decade later, Andrea Louise Campbell’s How Policies Make Citizens uncovered a wealth of evidence on how Social Security shaped political behavior at the mass level. Following the expansion of the program’s benefits between its passage in 1935 and the early 1960s, senior citizens’ resources and incentives for participating in politics exploded, as did membership in new organizations like AARP. These organizations helped to solve seniors’ collective-action problems, reducing the costs of political participation and providing members with selective incentives that ranged from the material (discounts on goods and services) to the solidary (social engagement) and purposive (political advocacy). Not only did the policy transform seniors from a relatively inert voting bloc into a powerful one; the “senior lobby’s lightning quick reflexes” laid to waste countless efforts to cut benefits.

This formula — new policies create new politics — contained at least a few wrinkles, as its exponents freely admitted. First, all policies make a new politics, but not always in a way that promotes political efficacy and social citizenship. Means-tested programs whose primary beneficiaries were politically weak and could be framed as undeserving do not create a powerful base of supporters at the mass level. Instead, their political endurance hinges on coalitions with more powerful economic actors. In the case of food stamps (later renamed SNAP), this was the agricultural lobby. Where Medicaid — the largest source of health insurance for low-income and disabled Americans — was concerned, this was a combination of state governors, health care providers, and, increasingly, private managed-care companies that mediated the relationship between the patient and the state.

Second, policies can also be designed in a way that prevents winners from recognizing their gains. As major social benefits in the United States are concerned, direct social programs like Social Security are the exception to the rule. While the American state came to have a far more important role in the lives of citizens during the course of the twentieth century, it was not through the highly visible Works Progress Administration–style projects of the New Deal but via indirect means: grants in aid to state and local governments, tax deductions for the interest on home mortgages, subsidies for employers who provide employees with health insurance and for college students who take out private loans. By the early 2010s, Suzanne Mettler had given a name to this vast but invisible archipelago of programs: the submerged state. Its invisibility meant that its beneficiaries did not become politically mobilized. If anything, Mettler concluded, the submerged state only helped to depress public support for government, especially where redistribution was concerned.

Third, if new policies created both winners and losers, the experience of losing rarely meant being knocked out of the competition for good. While the Tax Reform Act of 1986 may have nixed special tax privileges for hundreds of narrow lobbies, it did little to prevent them from getting back in the game. Within a decade, the losers had regrouped and secured new tax breaks. Similarly, while the Obama administration and congressional Democrats carefully crafted the Affordable Care Act to garner support from the insurance and health care industries, its passage only animated opposition from the losers: conservative ideological groups and organizations representing the small-business sector, which spent the next decade attempting to hobble the law’s implementation and erase it from the statute books.

Fourth, to the extent that policies create new politics, they tend to be defensive politics, as the beneficiaries of existing policies fight to preserve gains they have already made from attempts at retrenchment. Yet as Pierson’s student and later collaborator Jacob Hacker first argued in a landmark 2004 American Political Science Review article, the status quo is not a fixed point. Rather, policies must be routinely updated in response to changes in their environments — not only must Social Security payments be adjusted for inflation; they must be modified to account for fluctuations in the landscape of private pension benefits. Failure to do this results in what Hacker calls policy drift.

Since the 1970s, employers in the US largely shifted away from providing defined-benefit pension plans to offering defined-contribution plans, whose benefits are contingent on worker contributions and the rate of return. Because Social Security now stands as the only source of guaranteed retirement income insulated from market pressures, it has become a far more important source of income for retired workers than it was initially intended to be. For one in seven retired workers, Social Security now represents 90 percent of their annual income. For four in ten retirees, it provides at least 50 percent. While AARP and other senior organizations have been successful in preventing cuts to Social Security, they are far less successful at articulating a positive vision for adapting the program to prevent its slow erosion.

Policy Clienteles and Collective Action

Arguably the most common interpretation of these four complications to the “policy makes politics” formula is a technocratic one: if they are designed correctly, emancipatory social programs can create a landscape of organizations that help to compensate for the decline in the Left’s traditional power resources. As this theory goes, when policies confer adequate levels of benefits to a sufficiently large (hence politically powerful) constituency, they will trigger an endowment effect that mobilizes beneficiaries against efforts to retrench the welfare state. Those benefits will also provide beneficiaries (and the organizations that represent them) with material resources that can be converted into political action in the form of campaign contributions as well as the time necessary to attend meetings and the requisite level of canvassing and phone banking. And when social programs are highly decommodifying — when they emancipate workers from a dependence on the market — they have the potential to generate a sense of solidarity that strengthens social cohesion and allows for the endurance of left party coalitions for the longue durée.

There is a great degree of truth in this interpretation. If the voluminous literature on comparative social policy has taught us anything, it is that the United States government’s allergy to universalism and decommodification, as well its fetish for means-tested programs, low-profile tax credits, and indirect service delivery, has tended to accentuate the passive, anti-political character of American median voters.

Yet a preoccupation with policy and program among scholars, pundits, and political strategists comes at a cost. In particular, it oversells policy clientele organizations’ capacity to sustain the class compromises contained in social policy arrangements. Like all participants in the political arena, policy beneficiaries can only succeed in accomplishing their goals if they can solve the collective-action problem. That is to say, because they wish to protect a public good — say, adequate Social Security payments — they must find ways to coordinate action, mobilize resources, and sustain engagement despite having diverse interests and incentives to free ride. For several reasons, their ability to face these challenges will not stretch far beyond the maintenance and defense of narrow programmatic gains in the course of normal politics. Policy clienteles are less disposed to broad-based political action to stake out new terrain by pushing against the status quo to expand the range of available benefits or broadening eligibility. Nor are these organizations well designed to respond to frontal assaults that transcend normal politics — the sort of lawless gutting of benefits on display in the actions of the second Trump administration.

There are several distinct problems here. First, policy clientele organizations rarely possess a mass-membership base. Only about 10 percent of organized interest groups in Washington even have dues-paying members. Those that do are virtually never member democracies. While AARP boasts thirty-eight million members, these individuals have no ability to vote for leaders or to shape the organization’s policy decisions. This stands to reason, as members’ low, $20 annual dues payments make up only 15 percent of the organization’s annual revenues, which are drawn largely from royalties and partnerships with businesses that provide products and services, including insurance plans, to its members. AARP thus largely functions as a consumer organization. Even when it can mobilize a portion of its members to take collective action, it has virtually no monopoly on their loyalties. Medicare beneficiaries can be persuaded just as easily by AARP to phone their representatives in Congress as they can by managed-care companies that run Medicare Advantage plans, which routinely threaten that seniors will lose coverage if Congress tries to more tightly regulate the plans’ more predatory behaviors. Where public pensions are concerned, any cross-class solidarity AARP has managed to create has been punctured for the last five decades by the rise of private individual retirement accounts. While the organization helped to hold off attempts at privatizing Social Security during the George W. Bush administration, the political landscape for pensions remains fractured along class lines. Low-income retirees are far more likely than their high-income peers to support enhancing the generosity of Social Security benefits.

Second, policy clientele organizations’ disconnection from a member base enables them to pursue policy agendas that contradict their members’ interests. There is no better example of this than the AARP’s support for the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act, which provided a limited privatized add-on prescription drug benefit and accelerated the penetration of private managed-care companies into the Medicare program.

Third, even when policy clientele organizations can defend the interests of their members, they have incentives to do so in a narrow, risk-averse fashion. As analyses of disease-based advocacy organizations suggest, groups with large patient bases can and do aggressively leverage their numbers to advance key congressional committees. Nevertheless, these groups still tend to seek out “noncompetitive, distributive political environments.” Rather than forming coalitions with other organizations to push for structural changes in the US health care system, these organizations mobilize for narrow boosts in allocations within the National Institutes of Health budget. Similarly, when confronting proposals to introduce Medicaid work requirements during the first Trump administration that had the potential to disenroll millions of program beneficiaries, disease-based organizations were far more likely to push for narrower exemptions from the requirements for their members than to call for blocking the introduction of the requirements completely.

Fourth, regardless of the design of the program that they exist to defend, policy clientele organizations lack an obvious source of structural power. When compared to workers, policy beneficiaries have less capacity to disrupt economic activity through strikes or work stoppages. Unlike capitalists, broad policy beneficiaries have no control over investment or production. If anything, the power of policy clientele groups rests on their ability to rally beneficiaries to engage in the electoral arena by flooding the phone lines and inboxes of legislators and, in some rare instances, camping out in front of their offices to protest. Because they lack access to important choke points in the economy, the costs of successful collective action for these organizations exceed those of either firms or unions. Those costs are higher still when a benefit that a clientele organization seeks to preserve does not face an immediate threat, and the organization instead attempts to secure access to new benefits or to alter a policy in response to drift.

Relatedly, the benefits that policy clientele organizations seek to protect can be more diffuse than those located in a collective bargaining agreement. When compared to wages, working conditions, and fringe benefits, changes to even relatively simple universal social programs can be more difficult for voters to trace. The problem intensifies when benefits are delivered through a complicated web of public-private partnerships, as any survey researcher who has asked respondents whether they are on Medicaid surely knows.

In sum, even if policy clientele organizations can defend the programs that brought them to life, they lack important organizational advantages that both parties and unions — the traditional power resources of the Left — have long possessed. Whereas labor unions no doubt face challenges associated with organizing and mobilizing mass memberships, policy clientele organizations not only lack labor’s structural power; they are often disarticulated from a mass base and have organizational incentives that promote risk aversion and the pursuit of narrower policy gains.

The Failed Marriage

Although policy clientele organizations constitute important parts of the Democratic coalition, they have a difficult time exercising political leverage within the party. This is because they are rarely able to bargain with the most valuable chips on the table. While these organizations may be able to subsidize legislative activity with information and expertise, they rarely have access to mass-membership bases. Even when they do, their relationship with those members is often quite limited; few have the committees on political education long relied upon by organized labor. As a result, clientele groups cannot easily promise Democrats that they will be able to unlock important voting blocs in exchange for favorable action on their policy agendas. And those claiming to represent mass constituencies lack extensive campaign war chests that the most powerful organized interests in Washington possess. As a result, they have proven largely incapable of keeping the Democrats from drifting to the right.

The case of health financing reform is illustrative here. In the decades that followed the passage of Medicare and Medicaid, Democratic Party leaders continued to advocate for what was then called a national health insurance plan — a precursor to the Medicare for All proposals of recent years. Yet by the initial years of the Clinton administration, Democrats had abandoned this approach in favor of a market-based, employer-centered system that aimed to expand coverage through managed competition among private insurers. When that proposal proved no more capable of swimming through the maelstrom of insurance-industry countermobilization, the policy failure reinforced Democrats’ shift toward market-based health care solutions that became the backbone of the Affordable Care Act of 2010, otherwise known as Obamacare. Yet even on this more limited terrain, progressive health advocacy organizations like Physicians for a National Health Program and Healthcare-NOW were incapable of successfully lobbying for a modest but politically popular public option, which was rejected by the Obama administration and centrist gatekeepers within the party. A decade later, during the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 election cycle, a similar fate met grassroots efforts to place a Medicare for All plank on the party’s platform. While Bernie Sanders’s delegates to the 2020 Democratic National Committee DNC did manage to secure a compromise plank on “Achieving Universal Affordable, Quality Healthcare,” this plank did not live to see the party’s 2024 convention.

Even when policy clientele organizations have proved themselves capable of changing the Democrats’ ostensible agenda, the party has taken advantage of what the political scientist Kathleen Bawn and her colleagues refer to as the “electoral blind spot” to treat symbolic victories as if they were substantive. During negotiations over the Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration cut a deal with the pharmaceutical industry to prevent Medicare from negotiating drug prices. As prices rose over the next decade, patient advocacy organizations continued to push progressive Democrats to introduce price-control legislation. Gradually, Democrats began to take up the issue of prices but embraced legislation in which effects on prices were guaranteed to be muted at best. The language eventually incorporated into the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 allowed Medicare to negotiate the price of only a handful of drugs on an implementation timeline that was highly delayed.

Of course, policy clientele organizations did have some role in preventing the legislative repeal of the Affordable Care Act in 2017. Yet defensive coordination proved an easier task. First, it did not require persuading Democrats to shift their positions to the left. Indeed, Democrats were predictably unified in their opposition to repealing one of the party’s signature legislative achievements. Second, the coalition to defend Obamacare was composed not only of the policy’s direct beneficiaries but a phalanx of state governors, providers, and insurers that mediated the relationship between beneficiaries and the federal government. Finally, these support efforts benefited from the fact that, even when using the budget reconciliation process, Republicans had narrow margins in both the House and Senate as well as extensive internal conflict over the precise contours of the repeal legislation.

One could tell a similar story regarding the effectiveness of policy clientele organizations in altering the Democratic Party’s positions on any number of issues. Another set of examples can be drawn from efforts to reform higher education financing in the wake of the Great Recession. During the Obama administration, student interest groups pushed for regulations of predatory lending practices of for-profit colleges via the so-called gainful employment rules. Yet not only did industry pressure water down these regulations prior to their publication; they were rolled back almost entirely during the first Trump administration. Congressional Democrats failed to mount a serious pushback. While the Biden administration managed to reinstate some of these regulations, they were as good as dead by the time Trump returned to office in 2025.

By this point, a new and arguably far more politically savvy cadre of organizations succeeded in bringing the issue of student debt cancellation to the Biden administration’s attention. Debtors’ unions, notably the Debt Collective, were successful at winning a scaled-down debt-relief plan via an executive order. Yet these groups differed from traditional policy clientele organizations in a number of ways. Rather than organizing individuals around a benefit, they organized individuals around the shared economic condition of indebtedness. Perhaps more important, they framed their claims on the state not in terms of narrow policy gains but on the abolition of debt and structural changes in the political economy. Finally, whereas policy clientele organizations rely on lobbying and legal action, the tactics of groups like the Debt Collective were movement oriented, ranging from political education to debt strikes. In the near term, the victory proved to be short lived. Joe Biden’s plan became the subject of a lawsuit that eventually made its way to the US Supreme Court, which struck it down. By 2023, Democrats lacked the legislative majorities to make more enduring change possible. In the end, Biden’s approach to student debt was to expand the existing system of income-driven repayments but cap monthly payments at 5 percent of discretionary income. Nevertheless, at a critical juncture, the public debate about debt relief had shifted, with cancellation becoming a credible option. Survey results revealed that majorities of Americans supported plans for debt forgiveness.

Despite defeat in the courts, the Debt Collective’s relative success in appealing to the Biden administration helps to illustrate both the strength of membership-based organizing and, in turn, the weakness of traditional lobbying. Policy clientele organizations’ lack of strong ties to mass bases of members robs them of leverage with Democrats. Yet it also means that Democrats’ policy-based electoral appeals do not yield the returns that the “policy makes politics” formula is assumed to imply. The proof of this can be found in the considerable list of states whose electorates handed Trump at least a plurality of votes while also approving, among other things, expanding Medicaid coverage (Nebraska, Montana, Idaho, and Utah in 2018; Missouri in 2020; South Dakota in 2022) and guaranteeing abortion rights (Missouri and Montana in 2024).

Indeed, absent extensive organizational work to assist voters in making the link between party and policy, programmatic gains cannot substitute for party building. It is a long-standing feature of American public opinion that voters’ operational preferences for public expenditure can coincide with philosophical preferences for limited government. These disconnects have only been strengthened by the hardening of partisan identifications, which are now a stronger and more enduring source of identity than religious confession. For a policy victory secured by Democrats to result in electoral benefits, it would need to blast through the concrete of party identification. This would mean that the policy would need to have legible material benefits that voters would realize quickly.

The late programmatic style of the Democratic Party has yielded policies with the opposite effect. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are only the most recent examples of this submerging of public benefits. Consider the IRA’s low-profile tax subsidies for electric vehicles and clean energy, barely recognizable to consumers as a benefit resulting from a federal program, or the IIJA’s extensive support for broadband expansion as well as roads, bridges, and public transit investments — all of which are delivered through the private sector or state and local governments. As the political scientists Dan Galvin and Chloe Thurston have argued, even when policies have visible benefits, converting those benefits into party support would require voters to understand and favor the benefits of a new policy, link that policy’s benefits to a party, develop durable attachments to that party, and then vote accordingly. Even in the face of a Works Progress Administration–type program, this is simply unlikely.

In the wake of Democrats’ 2024 election losses, it is tempting to interpret the attenuated link between policy benefits and partisan electoral returns as proof that efforts to eke out progressive policy gains were not worth the effort. But this would misapprehend the reason for the disconnect. The kinds of policy feedback effects necessary to stabilize vote share across elections cannot be generated by parties that lack extensive connections to mass electorates. Neither the constellation of no-membership clientele groups nor the party apparatus itself is designed to build a party-policy linkage in voters’ minds. This not only makes it difficult for clientele organizations to tug Democrats away from their drift rightward but blunts the electoral impact of any working-class policy gains the party ultimately can sustain. These returns only help to underwrite a belief among the party’s leadership cadre that there is little electoral percentage in policies that advantage working-class voters, allowing Democrats’ retreat toward affluent suburbs to continue unabated. As the states that have historically made up the party’s strongholds lose population relative to Republican redoubts, there are obvious — and grim — implications for narrow presidential contests.

Resistance Without Reconstruction

Beyond abject horror at the administration’s authoritarian flex, professional political observers confronted the first few weeks of the second Trump term with a sense of outrage at the absence of more visible signs of outrage among Americans. By April 2025, even conservative New York Times columnist David Brooks could be found calling for a “national civic uprising.” In the face of Trump’s “shackling” of the “greatest institutions of American life . . . we have nothing to lose but our chains.” Yet even as protest activity ticked up to levels not seen during the first Trump administration, many of the most consequential actions unfolded in federal courtrooms, whose dockets swelled with challenges to Trump’s activities coordinated by states, local governments, federal employees, nonprofit organizations, and the policy clientele groups most directly affected by the administration’s blitz. The legal strategy ran into some immediate problems as it soon became apparent that the Trump administration had little intention of complying with some court orders directing the return of immigrants who had been wrongfully deported to an El Salvadoran mega-prison or preventing Musk and his team at the nebulous shadow agency known as the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) from illegally halting federal grant payments.

Yet for all its limitations, litigation had one advantage: it did not require the same level of collective action as other actions in the public sphere. Professional organizations scrambled to organize national Zoom meetings and “Days of Action.” Yet coordinating these responses proved difficult, especially given the reticence of Democratic leadership to take on a central role. Within a few weeks of the chaos, activist organizations like MoveOn and Indivisible had coordinated thousands of phone calls to House Democrats’ offices. Party leadership bristled at the implication that they were standing passively by. Rather, they wished to convey the image that the blame for government failures belonged with the majority party. According to one Democratic House member who declined to be named, “There were a lot of people who were like, ‘We’ve got to stop the groups from doing this.’ . . . People are concerned that they’re saying we’re not doing enough, but we’re not in the majority.”

By this point, “the groups” had become a kind of all-purpose epithet for the loose web of activist organizations that had developed over the previous several decades to challenge party leadership from the outside. Yet with the decay of traditional parties, such activist organizations — whatever their ideology or orientation to party politics — were now perennial features of the political scene. The emergence of professional-class social movement organizations, the sort that organized the 2017 Women’s March as well as a number of subsequent protests and campaigns, was a defining feature of the first Trump term. The organization known as Indivisible, founded in 2017, offers an object lesson here. Its roots can be traced to a PDF guide prepared by four former congressional staffers, each of whom had roots not only in the Democratic Party itself but in the complex of policy clientele organizations and nonprofits within the party’s orbit. Despite their relatively high levels of political and social capital, these policy professionals rejected institutional politics in favor of loosely coordinated grassroots strategy. This involved only a limited amount of formal organization. The group’s guide — widely circulated thanks to several celebrity Twitter accounts — provided a template used by nearly four thousand local organizations that outlined tactics ranging from demonstrations at congressional town halls to sit-ins and die-ins at congresspeople’s offices in response to Republicans’ 2017 bid to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Soon after claiming victory on the defeat of the ACA repeal, however, local and national Indivisible organizations began to splinter, and they proved incapable of organizing around what became the most significant driver of growing income inequality during the Trump era: the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. It was by then time to begin preparing for the 2018 midterm elections, an effort in which local Indivisible groups came to be highly engaged. In contrast to the national organization’s sheen of progressivism, the greatest beneficiaries of Indivisible organizations’ energies were moderate Democrats. Here, then, was a pattern: new grassroots organizations could provide valuable defense against shambolic legislative efforts to eliminate social programs. Yet on offense, they found themselves pulled in many directions at once. Despite Democrats’ success in the 2018 midterm elections, a positive agenda for defeating Trumpism proved elusive.

There is now a small literature devoted to debating the apparent depth, durability, and political imprint of the professional class’s movement awakening during the first Trump administration. And in the fashion of the social scientists who were highly enmeshed in these organizations, these books and articles merely suggest that the legacy of “resistance” politics is a matter for debate. What seems beyond question, however, is that these movements emerged out of the failure of the policy clientele organizations that supplanted the old politics of parties and unions. The invitation-only world of Democratic Party politics could now no longer suffice even as an acceptable career prospect for its leaders in waiting.

But if the likes of Indivisible represented a rejection of existing political forms, they nevertheless struggled to transcend their role as Trump antagonists, a role that their heterogeneous internal memberships practically made their destiny. Political expedience necessitated the formation of fluid, informal networks that had no obvious way to propel the simultaneous tasks of fundraising, grassroots mobilization, and agenda formation. Local Indivisible chapters could not count on regular showers of cash from deep-pocketed donors, which were concentrated at the national level. Once Biden took office, movement organizing could more easily be absorbed or held in abeyance until the unthinkable happened for a second time. Yet such organizations could not be expected to perform a purpose they were not built for. They lacked the scale and brokerage capacity to solve the coordination problems the Democratic Party had been incapable of solving. And though they likely helped to animate the Democrats’ midterm successes, they could not resolder the party’s links to large numbers of working-class voters.

Thus, as the chaotic weeks of Trump’s second term wore on, the clash between Democratic Party elites and activist groups over how best to respond to the increasingly lawless sacking of the administrative state and the assault on civil rights would continue. By late spring, a coalition that stretched to two hundred organizations, ranging from the American Civil Liberties Union to the Communication Workers of America, planned a day of protests that would ultimately mobilize millions of Americans. These events had been planned for months to coincide with Trump’s June 14 military-parade-cum-birthday-celebration, but they accrued new meaning as the administration attempted to juice its deportation numbers by snatching undocumented workers off the streets of Los Angeles and as it commandeered the California National Guard and deployed hundreds of marines to Southern California to quell the protests that followed. As public support for the protesters rose, some Democrats — including the mercurial California governor Gavin Newsom — seized on the moment, locking in on a more coherent message of opposition to authoritarian overreach.

Just the week before, however, a coalition of centrist Democrats gathered in Washington, DC, for a billionaire-funded WelcomeFest, an event whose central purpose was to admonish any principled opposition to the Trump administration in favor of a politics anchored by the careful fence-sitting, poll-watching, and triangulation that have been the Democratic leitmotif for decades. As speaker after speaker emphasized, it was not the party’s billionaire financiers or the last vestiges of the New Democrats but “the groups” that had led the party to electoral ruin. Whatever the outcome of this intraparty conflict, it may prove to have little bearing on the administration’s path of destruction or its political endurance. Neither the organizers of WelcomeFest, nor the network of traditional policy clientele organizations, nor indeed “the groups” are, at present, poised to easily reorient the conflict to make legible the consequences of tariffs, the DOGE coup, and the devastating implications of Trump’s budget for millions of working-class voters.

A New Look?

On February 18, 2025, Ken Martin — fresh from a victory in a hotly contested race for the chairmanship of the DNC — issued a five-page memorandum with the subject line “Democrats Will Fight Against Trump’s War on Working People.” Released on the same day Martin began a multistate tour to meet with state party leaders and local candidates, the memo laid out what he saw as Democrats’ most urgent task: “Repairing and restoring the perceptions of our party and our brand.” “It’s time,” Martin said, “to remind working Americans — and also show them every day — that the Democratic Party always has been and always will be the party of the worker.” The scene for this new beginning was a diner in Pittsburgh’s Strip District, where Martin met with members of the United Steelworkers.

That restoration hinged on refiguring the political calculus, Martin suggested. In a stark contrast with Democrats’ 2024 presidential rhetoric, the new chair ditched the ambiguous banner of democracy (a word that did not appear in the memo) for a more materially grounded alternative: “union power.” “As an organizer, I know, alone, no one person can take on the ultra-wealthy and the powerful,” Martin said. “But by joining together in a union, working people have secured better wages, workplace protections, health care, and the weekend. Because here’s the thing: unions expand opportunities for all workers — not just those who are members.” Consistent with this formula, Martin’s memo reinterpreted the first weeks of the new Trump administration as class warfare by enumerating the ways in which the president “and his billionaire backers are hell-bent on attacking working families and dismantling the unions that protect workers in order to enrich themselves.”

Martin’s pivot toward the material consequences of the Trump–Musk putsch reflected what was becoming the top-line interpretation of Democrats’ electoral struggles. “Too many people right now feel like our party has forgotten them, that they have been left behind,” he told steelworkers at the diner in Pittsburgh. “They’re working their asses off, and they can’t get ahead, and that’s what we have to really recognize. My brother who’s a union carpenter, he voted for Democrats his whole life. And then in ’16, and ’20 and ’24, he voted for Trump. My father-in-law who’s a beef cattle farmer in southern Minnesota — same deal.”

This opening was much in keeping with Martin’s pitch to the DNC during the race for chair. In his public appeals during that contest, he had gone so far as to quote Florence Reece’s 1931 labor anthem “Which Side Are You On?” “Are we on the side of the robber baron, the ultra-wealthy billionaire, the oil-and-gas polluter, the union buster?” he asked. “Or are we on the side of the working family, the small business owner, the farmer, the immigrants, the students? Let me tell you: I know which side I’m on.”

If articulating this new look (or rather the rehabilitation of an old look) for Democrats was ultimately to become Martin’s most visible signature, his presentations to DNC members also made clear that he saw branding as somewhat meaningless in the absence of broader organizational transformations. Of the ten elements listed in Martin’s proposed “New DNC Framework,” “Democratic Brand Identity” was the last. In what could easily become a postscript to Schlozman and Rosenfeld’s Hollow Parties, Martin’s priorities centered on party building. This meant, among other things, reinvigorated funding to state party organizations via Democrats’ existing State Partnership Program, a new effort to build community-level party organizations as well as new youth-oriented clubs. Rather than describing the party as a means of brokerage for existing policy clientele organizations, Martin’s framework imagined a party composed of its own local organizations capable of connecting voters to leadership.

Martin’s call for party renewal was in harmony with what is becoming a conventional wisdom among political scientists. Having been reduced to the status of a brand and an election-season vote procurement operation, the theory goes, parties have divested themselves of their most important capacities: the ability to mediate the relationship between the rulers and the ruled and to organize a number of voters adequate to the task of bringing about substantial change. The Democrats’ renewal thus requires more than replenishing the resources of withered state and local party organizations. It demands regular face-to-face engagements with voters on a regular basis to root the party in daily life through meetings, speaker series, and leisure activities. To generate meaningful participation, these activities must be pursued in conjunction with local civic infrastructures. These newly revived party organizations must also have channels that link public opinion at the grassroots to the national party agenda.

One might suppose that Martin’s election as DNC chair signals something about party leaders’ understanding about the urgency of organizational renewal. This remains to be seen. Yet even if Democratic power brokers were uniformly sanguine about the need to build up associational strength at the local level, the DNC is but one facet of the Democratic Party. While Martin appears to be more ambitious in leveraging the committee’s fiscal and ideational resources than his predecessors, it would still take a generational transformation at all levels of the party to build new associational structures across more than three thousand US counties.

Moreover, and perhaps more significantly, any renewal project will have to grapple with the numerous functions that have, for the last half century, been delegated to organizations outside the formal control of state and local party leaders. On the one hand, a significant share of financial contributions that would otherwise go to party organizations are now spoken for by a battery of advocacy organizations, nonprofits, and think tanks that constitute the political universe of each major political party. At the local level, it is nonprofit organizations, not political parties, that play the predominant role in service provision and political incorporation. The task of mobilizing voters between elections — especially, though not exclusively, working-class Americans — has also grown more formidable as voter identification with the Democratic Party has sunk in recent years. In a 2024 Gallup poll, the largest political bloc in the United States — roughly 43 percent of US adults — identified as independents. By contrast, 27 percent of adults identified as Democrats, a new low for the party in Gallup’s data.

In sum, any party reform or party building that occurs will play out on a political terrain already dense with activity, where competition for resources, loyalty, and energy will remain intense. Proponents of associational party building are well aware of this challenge, which is why they emphasize that parties must forge “robust links to grassroots associations in civil society.” One can no doubt locate cases of partnerships between local party organizations and civic associations. But a few fine days do not make a summer. To revive local party organizations will require serious consideration of how to offer voters, donors, and organizational partners enticing incentives for participation they cannot obtain elsewhere.

That assumes, of course, that the leaders of local party organizations are in fact interested in renewal and a robust network of interorganizational partnerships can be summoned to support such a project. In many American cities, however, the largest reserves of political energy reside in organizations and coalitions external to the Democratic Party, and often in competition with it. In Pittsburgh, for example, a rusted-out party committee could not, for all its efforts, prevent the election of Sara Innamorato, the progressive challenger in a 2023 race for Allegheny County executive. In a tightly contested primary, Innamorato relied on a robust network of support from service workers’ unions and local advocacy groups whose turnout operation Democrats simply could not match. Strong associational parties will no doubt contain internal divisions on policy and strategy, yet they cannot operate without the capacity to organize voters. In cities where the party organization is moribund, any effort at renewal will likely begin externally rather than internally, via conflict rather than collaboration.

It is too early to say whether the Trump–Musk assault on the state will be a deus ex machina for Democrats. If the first months of Trump’s second term are any indication, individuals’ understanding of the relationship between the president’s actions and disruptions to their access to social programs (or the operability of government writ large) is limited.

This cannot be attributed solely to the submerged character of many social programs in the United States, delivered through the tax code or through networks of third-party providers. Nor is the state’s invisibility the result of the complex, taken-for-granted features of government, like the quality-assurance measures thought to protect Americans’ Social Security benefits from a horde of Silicon Valley marauders. Rather, the state’s invisibility in Americans’ lives — the very thing that makes it possible for Trump to assault public programs without an immediate political crisis — has at least as much to do with the disorganization of political parties into loose networks of policy claimants and the absence of clearly articulated political programs. Illustratively, some of the largest public protests and rallies to raise public consciousness about Trump’s power grab were coordinated by individuals and organizations outside of the Democratic Party.

The events of these initial months of Trump 2.0 provide further indications that organizational renewal is likely to result from external pressures on the Democratic Party as opposed to conscious recalibrations within its ranks. The labor movement has the potential to play a leading role here. Federal workers are on the front lines of Trump’s purge, which has itself occasioned a flood of over fourteen thousand new members into the ranks of the American Federation of Government Employees in just five weeks. Greater militancy among these workers could have benefits that redound beyond federal agencies by clarifying the material stakes of the Trump assault for workers across the country. Trump’s executive orders could also animate new forms of mobilization outside the state. Attacks on federal funding at research universities, for example, could help to create new opportunities for cross-class solidarity within the ranks of academic workers. Finally, a renewed assault on the National Labor Relations Act — which has ironically come to represent a pair of shackles for the labor movement — could also lubricate experiments with alternative approaches to expanding the labor movement via sectoral bargaining at the state level. These social and economic perturbations, as much as any episode of party reform, highlight the urgency of creating a culture of solidarity that has for so long been missing from the American left.

Whether the effects of Trump’s assault on the state and the countermobilizations it animates will be cumulative is impossible to forecast. What seems far more certain at this point is that, left unchanged, the organizational structure of the new politics — which has proved incapable of playing offense at the ballot box — will find its defense outflanked as well.