Gary Dorrien Is Christian Socialism’s Greatest Champion

The theologian and historian Gary Dorrien has made it his mission to chronicle and revive the tradition of Christian democratic socialism. His work reminds the American left of our project’s spiritual dimensions.

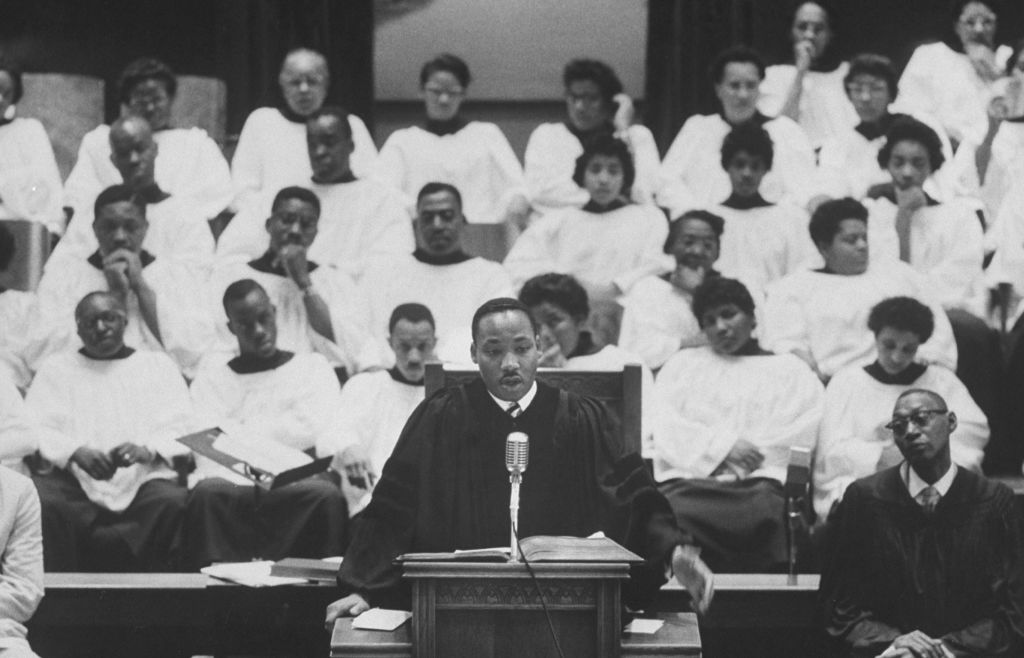

Christian socialism is one of the most powerful currents in American left history. Theologian and historian Gary Dorrien has spent his career making sure we don't overlook its contributions and potential. (Donald Uhrbrock/Getty Images)

Conservatives have often accused socialism of being a materialistic and spiritless philosophy. The most popular version of the charge is that socialists focus on making a happier world for all because they can’t imagine anything more spiritually demanding than the pursuit of happiness. The great reactionary author Fyodor Dostoevsky captured the critique brilliantly in his novella Notes from Underground, imagining a world where secular leftist reformers remove all the sources of pain and spiritual agony, and hypothesizing that human beings would smash it simply to feel liberated from a lifetime of mechanical gratification.

The great religions of the world impose serious moral demands on us, asking us to contemplate the eternal rather than the merely transitory and profane. Socialism’s atheism and materialism, the argument goes, are no substitute for that.

The charge belies the fact that many of the most spiritually sensitive and thoughtful souls in modern history have felt the pull of socialism. This should come as no surprise. As the social democratic philosopher Charles Taylor notes, the egalitarian and universalistic ethics of the modern world in fact make far more demands on us than the hierarchical and selective ethics of many on the Right. Theologians and religious activists like Paul Tillich, Martin Luther King, R. H. Tawney, and Jane Addams all saw in socialism a way of taking seriously humankind’s most important demonstration of spiritual commitment: the realization of eternal justice within time.

In the United States, few have done more to keep the flag of religious — and especially Christian — socialism flying than Gary Dorrien. Currently the Reinhold Niebuhr chair of social ethics at Union Theological Seminary in New York, Dorrien has spent years canonizing and illuminating the tradition of Christian socialism specifically and the religious roots of social democracy generally.

Gary Dorrien, Seer of Christian Socialism

In his spiritual autobiography, Over from Union Road, Dorrien describes growing up in working-class Michigan as a formative experience. Not coming from an especially religious family, a key moment in his life was encountering L. D. Reddick’s biography of Martin Luther King Jr, Crusader Without Violence. He was struck by King’s combination of activist energy and intellectual rigor. This led Dorrien to his own life of religious intellectualism and political activism for democratic socialism.

Reading the Bible seemed impossible to me — what were you supposed to do with the sprawling mass of whatever it was? Start at Genesis and just keep reading? That approach broke down twice. The artwork, however, was another matter entirely, reinforcing my fixation with the cross, as our family Bible had artwork depicting the stations of the cross. Reddick was long on narrative and mercifully short on intellectualism, which was not how I experienced King’s book Stride Toward Freedom (1958). His chapter on what he studied at college and seminary sailed far above my head, a parade of Walter Rauschenbusch, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, Mohandas Gandhi, Reinhold Niebuhr, and some personalist philosophers and theologians. This book planted the seeds of who I became.

Growing up, Dorrien absorbed an immense array of books, which planted the seeds of his later encyclopedic style. Like many theologians and philosophers, Over from Union Road spends a lot of time on major literary encounters: Immanuel Kant, G. W. F. Hegel, Martin Heidegger, Alfred North Whitehead, black liberation theologians, socialist thinkers from Marx to young Niebuhr, and more. These became the inspiration for enormous works of his own, many of them historical, which chronicle the emergence and development of Christian leftism in the United States and elsewhere. One of his most substantial contributions is chronicling this story theologically. Dorrien’s intellectual and social histories bring well-deserved attention to figures who deserve to be better remembered and more carefully studied by nonreligious leftists too.

In Social Ethics in the Making: Interpreting an American Tradition, Dorrien discloses a still little-known history of left-Christian intellectuals in the United States across more than seven hundred pages, including figures like Reverdy C. Ransom and Paul Tillich. Founded in the 1880s, proponents of the “social gospel” founded a tradition known as “social ethics.” They rejected what they saw as the crass individualism and materialism that ran rampant through society during the Gilded Age, and included members from all religious denominations, who brought their distinct attitudes and convictions to bear on the material.

Born in Flushing, Ohio, Ransom became a pioneer in applying social ethics to the condemnation of racism. Declaring that a man like John Brown “appeared only twice in a thousand years,” Ransom stressed that “the situation for blacks in the USA was terrible and desperate . . . yet it was also distinctly promising, filled with redemptive possibilities that reverberated to the ends of the earth.”

The passionate, angry Ransom cuts a very different figure from the ultrascholarly Paul Tillich. Born in Germany in 1886, Tillich seemed destined for a life of middle-class propriety — until World War I, in which he served as an army chaplain. In The Spirit of American Liberal Theology, Dorrien describes how the war “burned a hole in Tillich’s psyche, subjecting him to four years of bayonet charges, battle fatigue, nervous waiting, the disfigurement and death of friends, two nervous breakdowns, and mass burials at the western front with the Seventh Division.”

Afterward Tillich was forever changed. In the 1920s, he and his wife embraced a life of bohemian experimentalism in socialist Berlin, for which many have criticized him from a religious standpoint. He became attracted to the democratic socialism of the German Social Democratic Party and was horrified by the rise of Nazism. In The Socialist Decision, Tillich called on Germans to make a “decision” for socialism and against the blood-and-soil nationalism of fascism. This activism made Tillich a marked man in Nazi Germany, and he was forced to flee to the United States. Tillich became world-famous for major works like the multivolume Systematic Theology and shorter guides like Dynamics of Faith.

Tillich was revered — and sometimes mocked — for his combination of otherworldly intellectualism and accessible spiritual writing that popularized ideas like God as the name for “what concerns man ultimately.” But his religious socialism remained integral, even if it had to be quieted down in the context of Cold War America. Dorrien notes how “Tillich’s theology of religions thus rephrased his original theology of religious socialism” in its description of justice as a universal principle common to all faiths, the denial of which is “always demonic.”

Retrieving American Democratic Socialism

More recently, Dorrien’s work has turned to canonizing the great figures in the European social democratic and American democratic socialist traditions — most notably in two big books for Yale University Press: Social Democracy in the Making and American Democratic Socialism. The latter is the more significant of the two. Social democracy and socialism remain well-known traditions in Europe, with figures like Karl Marx, Eduard Bernstein, R. H. Tawney, and Rosa Luxemburg all making seminal contributions. But the canonical history and figures in American democratic socialism remain obscure, even to many American leftists. This makes American Democratic Socialism probably the most politically salient of Dorrien’s works.

Dorrien aims to dispel two important clichés in American Democratic Socialism. The first is that Americans were never attracted to socialism because the country’s innate prosperity inoculated ordinary citizens against it. Dorrien soberly notes that from the slave system in the American South to the Gilded Age slums of Chicago and New York, there has always been more than enough suffering in America to catalyze a major socialist movement.

This leads to the second cliché, which is that there were no serious efforts to build a mass socialist party or movement. Jacobin readers will of course be familiar with the saga of Eugene Debs and Norman Thomas’s Socialist Party. In the 1910s, Debs won hundreds of thousands of votes for the socialist ticket on the strength of an antiwar, pro-free-speech platform. In the 1930s, Dorrien describes how Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal sapped much of the Socialist Party’s leftist energy. But he complicates the usual story of the New Deal buying off the potentially revolutionary lower orders by pointing out how Roosevelt invited Thomas to the White House and urged that he “supported most of what they wanted, except nationalizing the banks.” After much of the signature New Deal legislation passed, Thomas worked to remind grateful audiences that many of its “programs came from the Socialist platform.”

One core takeaway from Dorrien’s book that links it to his broader project is the enduring significance of religious socialism in the United States. Among the most successful left-wing pushes of the twentieth century was the civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s, led by spiritual leaders like Dorrien’s beloved Martin Luther King Jr. Dorrien traces the eclectic roots of King’s Christian socialism: his “socialist worldview” drew on a dizzying array of influences, including Walter Rauschenbusch, W. E. B. Du Bois, Mordecai Johnson, A. Philip Randolph, J. Pius Barbour, the early Reinhold Niebuhr, Benjamin Mays, Walter Muelder, and Bayard Rustin. King, per Dorrien, was committed to educating “the public about Socialism versus Communism.”

King’s first crusade was for racial justice and an end to Jim Crow. But near the end of his career, he began linking racism to the corrupting influences of capitalism and imperialism, describing the three self-reinforcing evils of society as racism, materialism, and militarism. Each had a corrosive effect on the soul of America, and King worried they were leading the country down a dark path. Toward the end of his life, he had become too radical for the Democratic Lyndon B. Johnson administration, which expected him to toe the line on the Vietnam War. But King felt called to oppose his country’s militaristic imperialism.

A Search for Roots

Dorrien’s work is a showcase of what socialist scholarship ought to look like. Despite his erudition, he is appropriately humble about his place in a long tradition with deep roots. His work is very rarely stamped by a pronounced individualism; even his autobiography shows the need to think with others. No surprise he describes his outlook as an “I-we-we-I” one, in which the living and the dead take on far greater significance than any individual intellectual or spiritual creation.

But this kind of labor is vital in itself. In Hijacked, the philosopher Elizabeth Anderson notes how, despite its influence, the canon of social democratic and democratic socialist thinkers remains largely unknown even to educated people. Far from just a gap in our knowledge, this has distinctly ideological implications. Without an awareness of the history socialists draw upon — the shared problems faced, overcome, and remaining — it becomes far harder to understand what it means to be a socialist at all. The impact is to cut the movement off from itself.

What Dorrien has accomplished over a long career is essentially a restorative task. Most obviously, he’s done much to clarify the tradition of Christian and American democratic socialism, which remains unclear to many. But more to the point, Dorrien has helped North American socialists recognize ourselves as part of a proud heritage characterized by passionate commitments to social justice coupled with an inward conviction of spirit.