The Testament of Ann Lee Is the Wild Shaker Musical You Crave

When it comes to The Testament of Ann Lee, you’re either someone who wants to see a long, sometimes harrowing musical about the woman who founded the Shaker religion, or you’re most definitely not. Hopefully you are.

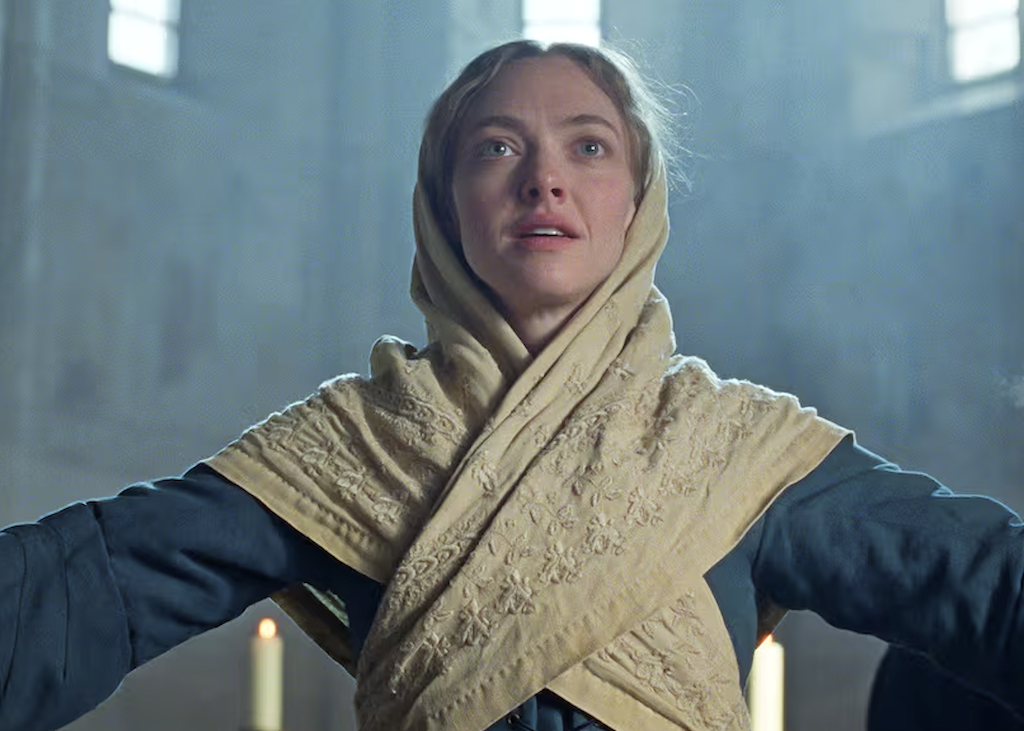

Amanda Seyfried in The Testament of Ann Lee. (Searchlight Pictures)

The most common reaction to The Testament of Ann Lee is to note that you’ve never seen a movie like it. True enough!

It’s about the founding of the Shaker religious movement by the title character, an eighteenth-century Englishwoman who came from laboring-class poverty and found spiritual inspiration in the Evangelical revival of the era. Ann Lee suffered such trauma in her marriage, with all four of her children dying in infancy, that it led her already intense religiosity to the idea that celibacy was the only way to achieve gender equality and unite errant, carnal humanity with God.

Directed by Mona Fastvold and cowritten with her longtime partner, Brady Corbet — who also collaborated on the script for The Brutalist (2015), which he directed — The Testament of Ann Lee dramatizes how Lee (Amanda Seyfried) was inspired by an alternative, woman-led religious group called the “shaking Quakers” because of their loudly vocal, full-body participation in confessions of sins and ecstatic communal dance. It’s these increasingly mesmerizing, rhythmic, angular “musical numbers,” brilliantly choreographed by Celia Rowlson Hall (Vox Lux), mostly set to traditional Shaker hymns scored by Daniel Blumberg (The Brutalist), that create the film’s most sensational impact. The film was a wow at many film festivals — I tried repeatedly to see it at the Toronto International Film Festival, but every screening was sold out — and it did well enough in limited theatrical release to earn it a wide release.

Lee begins preaching her breakaway Shaker beliefs at a time when women were not generally allowed such public assertiveness. Defiant in the face of violent attacks and a period of grueling imprisonment, Lee’s visionary faith brings her a small following who believe she is the second coming of Christ on earth, in female form. Her brother William (Lewis Pullman) is her devoted right-hand man. Ultimately, they opt to leave England behind and sail to America, a land supposedly free of religious persecution. Basing themselves in rural New York State, they build the utopian Shaker movement, which also embraces racial equality. But their strict commitment to nonviolence during the American Revolution brands them as traitors in the eyes of many.

Even critics who don’t like The Testament of Ann Lee acknowledge its uniqueness and offer high praise for Seyfried’s remarkable performance. She carries the film with intense conviction, sings beautifully, and dances as if she’s genuinely moving into a spiritual trance. She’s been nominated for many Best Actress awards, including the Golden Globes and Critics’ Choice Awards, though the film was strangely shut out of Academy Award nominations.

Although the film has large flaws in its pacing, I liked it. This is partly out of my own dark, morbid, unkillable religious streak that I presume was inherited from some of my seriously wild-eyed backwoods forbears. Anything dealing with the “Burned-Over District” — a swath of New York State that got scorched in the nineteenth century by the intensity of charismatic preaching and religious fervor that overtook the region — has got my undivided attention.

This era of feverish, vision-seeing religiosity emerged from the first and second “Great Awakenings,” fervent new eighteenth- and nineteenth-century systems of belief, including Shakerism, that emerged from Britain and Europe and swept through North America. The Burned-over District era gave us the Mormons, the Seventh-day Adventists, and the Spiritualists. Radical reformist politics accompanied several of the “awakening” religions and inspired abolitionist, feminist, prohibitionist, and vegetarian movements, along with utopian experiments in communal living.

Representing such rival religious movements in The Testament of Ann Lee is a character played by Tim Blake Nelson. He’s a preacher in a doomsday sect who is frantic when the world doesn’t end during a total eclipse of the sun, as he predicted. He and his followers go back to the drawing board and give Shakerism a try.

Oddly enough, the least successful element of The Testament of Ann Lee is her visions. Lee sees them from early childhood on, and without exception they’re represented to us in the most banal way. A montage of religious paintings by old masters, some lame snake in Garden of Eden imagery, and a dull flash of a CGI angel are weak sauce typical of modern Western filmmakers. Whenever these people deal with a biographical character whose extraordinary accomplishments were directly motivated by signs and messages from God, these directors wimp out in the most contemptible fashion. The 2019 film Harriet, featuring a riveting performance by Cynthia Erivo as Harriet Tubman, has visions so pallid they’re like something out of a pamphlet for New Age spa treatments. And the less said about the inane visions attributed to Nat Turner in Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation (2016) the better. Especially because the real Turner described the bloody, mind-blowing images that overcame him and inspired his insurrection, and they were faithfully transcribed before he was executed. All you’d have to do to achieve powerful cinematic effects is have the elementary guts to treat his descriptions as part of your script and film them.

Future directors of films about eighteenth- and nineteenth-century revolutionary religious visionaries, I have just this to say: if you can’t take the heat, stay out of the kitchen.

A deplorable cop-out like that points to other weaknesses in the film, which, again, suggest a failure of nerve, or perhaps of imagination, in the director. After a while the Ann Lee story suffers from a certain sameness that has to do with a refusal to take on the scarier aspects of following a charismatic woman who, if we trust this version of events, never had any doubts about her own awesome status in the world as God’s daughter, the Christ, his chosen representative on earth.

There’s just one moment in the film that hints at it. While on board a leaky ship headed for America, Lee and her followers are practicing their admittedly noisy version of worship on deck and exasperated sailors and fellow passengers begin shouting “Shut up! Shut up!” like characters from Monty Python. Seyfried as Lee casts a baleful glare out of pale saucer eyes toward the hecklers that makes you realize why charges of witchcraft were flung at Lee. Not just for typical misogynistic reasons but out of straightforward fear of someone who seems to have ominous powers as a seer and leader beyond what can be accounted for in ordinary life.

Fastvold and Corbet structure the tale so that it’s told by Lee’s devoted follower and friend Mary Partington (Thomasin McKenzie), and her worshipful attitude toward Lee in her sufferings and triumphs prevails. Lee seems to have endured no Christ-like doubts about the extremes of her faith or the severity of her trials, no “My God, why hast thou forsaken me?” moments. And there are no serious schisms or betrayals within the community.

A couple of young Shakers in love who find they can’t do without sex leave the fold early on, and Lee’s husband also refuses to stay the celibate course, but otherwise the internal workings of the Shaker community are strangely smooth sailing. All the strife comes from the outside and it’s largely represented by faceless, depersonalized male ruffians who assault the Shakers in unruly mobs.

Still, it’s often a beautiful work, shot on glowing 35mm film (and blown up to 70mm), and reverent about the spare but lovely rural way of life of the Shakers. It’s late in the film when we finally get a look at the Shaker aesthetic of simple but rigorous design, reflecting their dedication to hard work, quiet orderliness, and careful craftsmanship. It’s so opposed to the typically ugly, chaotic, materialistic clutter of life in the United States, it may give you a spiritual pang.

And no doubt those Shaker “dance numbers” are weirdly thrilling.

But you don’t really need critics to tell you whether you want to see The Testament of Ann Lee or not. The sparest description will convince you. You’re either someone who wants to see a long, detailed, sometimes harrowing biography of the woman who founded the Shaker religion — a religion that’s so faded out of contemporary life, it has only two surviving members — or you’re most definitely not.