Minneapolis Is Going on Offense Against ICE

We spoke to a Minneapolis organizer about the community-organizing infrastructure there in response to ICE, why targeting corporations that profit from ICE is working, and how other cities could do the same in their fight against ICE terror.

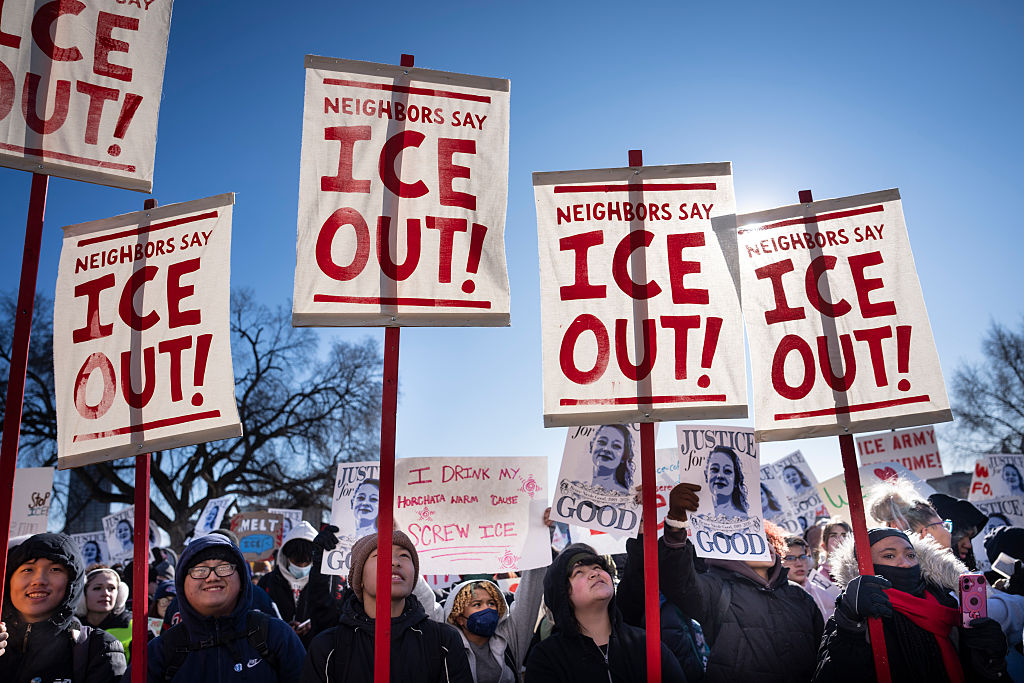

A campaign led by the Twin Cities Sunrise Movement has led to an impressive string of local victories, including getting a local Hilton to refuse service to ICE. (Bridget Bennett for the Washington Post via Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Eric Blanc

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Border Patrol’s terror campaign in Minnesota has taken the lives of Renee Good and Alex Pretti and led to the abduction of five-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos, among countless others. Minneapolis has answered with an astonishing surge of courage. Neighborhood Signal chats and daily community-watch patrols have turned sidewalks into lines of mutual aid and defense, while the January 23 statewide general strike proved a willingness on the part of residents to stop business as usual in defiance of ICE’s violent repression.

The Twin Cities Sunrise Movement has pushed the resistance onto offense, targeting the Hilton hotels that quietly house ICE agents. This campaign has led to an impressive string of local victories, including getting a local Hilton to refuse service to ICE, sparking outrage from the Department of Homeland Security and the subsequent capitulation of Hilton nationally to the administration.

Jacobin’s Eric Blanc spoke with Aru Shiney-Ajay, Sunrise Movement’s executive director and a lifelong Minneapolis resident, about Minneapolis’s organizing pushback and how ICE’s opponents can go on the offensive nationwide by pressuring companies like Hilton, Enterprise, and Home Depot to stop collaborating with the agency.

What has it felt like to be a Minneapolis resident and organizer these past two months?

It feels like living in a war zone. I was really reluctant to say that at first, but every few hours I get a Signal message about ICE — usually within walking distance of me. Two weeks ago, I had a friend who had a gun pointed at their head by ICE agents, and I have friends who’ve been dragged out of their cars and detained. It feels like you’re walking around and at any moment you could be grabbed and kidnapped. It’s come to a point where something as simple as recording an interaction with ICE can be met by being shot, which is a really different level of fear to carry around.

At the same time, it’s also the most organized community I’ve ever experienced anywhere. We’ve hit a density in Minneapolis where over 4 percent of every single neighborhood is in a Signal chat at the neighborhood level — and it might be higher, because those are just the Signal chats we’re centrally tracking. In St Paul, there’s a neighborhood called Frogtown. It’s heavily Hmong. Every day, we create a rapid response Signal chat for people actively patrolling in Frogtown, and every day by 11 a.m., that chat hits its limit of a thousand people — which is to say that, at any given moment in one neighborhood, there are a thousand people out patrolling.

Can you speak more about the sense of community that has emerged?

I feel more from Minnesota than I’ve ever felt. And I’ve grown up here. But now I know as I’m walking down the street that I have hundreds of people who will swarm to help me if needed, and that I will swarm to help them.

There are these intense protest moments — like the number of times you pick someone up after they’ve been tear-gassed and use snow to wipe the tear gas from their face. But there’s also this everyday feeling of solidarity, because everyone is walking around with whistles. If you hear a whistle, suddenly people start swarming toward you. I’ve never felt so backed up. It feels like we’re all on a giant team together as a city. It’s incredible.

It’s like building a muscle of solidarity across race, across class. It’s something the Left talks about a lot, but I’ve never experienced it like this. And it’s truly ordinary people — it’s not majority organizers or activists. It’s people who’ve never organized a day in their lives but know something wrong is happening and want to do something.

Can you speak more about the fear and how people have overcome it?

Part of it is that it starts really small, and then the small things become more risky, and you don’t want to give them up. Standing and recording with a phone was what we were first training everyone to do. Monarca Unidos, an immigrants group here, trained something like 24,000 people on legal observer roles: standing and recording with a phone.

Everyone was prepared to do that, and then that became risky. But it was an identity people had taken up — “I can stand here and record with a phone” — and people didn’t want to back away from that.

Another example is that delivering groceries to undocumented people who can’t risk going outside was floated as a low-risk thing you could do. But in the last week, ICE agents have started following around white people carrying grocery bags, because they think that will lead them to undocumented people.

So now the people delivering groceries — which, again, is a very low-risk thing — have been trained to know that in case ICE grabs them, they should never write the list of addresses down digitally. You write it on a physical piece of paper, and if ICE grabs you, you eat the piece of paper.

That type of thing is motivating courage right now. What we’re doing is very basic: it’s giving people food and walking around recording on our cell phone. And when you’re not allowed to do that — when that becomes high-risk — there’s a sense of, my basic rights are being violated.

Obviously it’s harder to go and directly confront an ICE agent. That’s high-risk. But delivering groceries shouldn’t be high-risk. It violates people’s sense of dignity and basic rights, and that’s what creates courage.

Progressive unions and community organizations in Minneapolis called a day of “no school, no shopping, no work” on January 23. How was it?

I was really proud. I was walking through the crowd and felt like crying in a lot of moments — it was a lot of people. I know several people, including some immigrants, for whom it was their first protest. I know a lot of people who called out sick from work, too — hairdressers, drivers, all sorts of different people. I saw a lot of small businesses closed — not usually large ones. But that was very touching.

It was a fantastic start. We have a lot further to go to actually flex our muscles by shutting down the economy. But even popularizing the idea that regular people have control over how society works was essential. Real general strikes that can shut down an economy don’t happen in a week — it’s going to take a lot more work. But what we did was incredible.

Can you speak about the work the Twin Cities Sunrise Hub has been doing around hotels?

We’ve seen incredible rapid response networks across Minneapolis and the country. That’s fantastic and necessary. But Sunrise’s assessment was: we also need an offensive component. Because how are we going to stop ICE from doing what it’s doing?

The framework we use is “pillars of support.” What are the literal ways that support ICE’s ability to get around and operate in our city? Back in November, we did an analysis and identified a couple pillars: rental car companies, hotels. We also identified transportation on the roads, restaurants, and food delivery to the Whipple Building, which is where they’re operating deportations and detentions. There are any number of supports. Then we narrowed it down: Which do we have the most control over and access to, so that we can nonviolently interfere with them?

Starting in late November and early December, we decided to go in on a hotel campaign. We built extensive infrastructure to identify where ICE was staying, then started showing up in the middle of the night and making noise outside.

The logic is simple: if you make noise outside hotels, ICE agents won’t want to stay there, and hotels won’t want to house them. If enough hotels don’t want to house ICE, then they don’t have somewhere to stay. It’s both about actual logistics and also socializing the idea that ordinary people are running institutions that support ICE to operate.

I’m excited to do this for hotels but also to have people understand the logic enough that they start thinking about it everywhere ICE interacts: rental car companies, restaurants. It’s been working really well with hotels in general, and Hilton in particular.

Anti-ICE protesters are having a rolling noise demo and protest in downtown Minneapolis targeting hotels where federal agents are reportedly staying — the Canopy by Hilton and the Renaissance Minneapolis Hotel. Police have just arrived as we are posting this. pic.twitter.com/BK5nxs1BG3

— UNICORN RIOT (@UR_Ninja) January 10, 2026

We had one hotel publicly refuse to house ICE, which became a big national news story when DHS went after them. That’s a hotel we were targeting, and it was mostly because of our pressure. We had two more hotels temporarily shut down to avoid housing ICE and keep staff safe.

We’ve had two other hotels say they are kicking ICE out because they want to avoid noise demonstrations. We think that’s happening elsewhere, too. There are several other places where managers or hotel staff told us ICE left after noise demonstrations because they don’t want to be woken up in the middle of the night.

So it’s working — and we need to scale it up in Minneapolis and nationally. The real thing we want is for hotel companies to withdraw support for ICE. Ideally it’s not manager by manager, but creating a wave of hotels that are doing it is the first step.

How do you see the role of employees — white-collar or frontline workers — at these companies?

The workforce organizing piece is key. Immigrants are running a lot of these hotels. From our experience, a lot of hotel workers don’t want ICE there, and they request noise demonstrations at their hotels, or they let us know when ICE is staying.

We’re very clear with organizers and participants that we never direct anger at hotel staff, who aren’t the reason ICE is staying in the hotels, and we never engage in property destruction. There’s an opportunity for collaboration and strategy with workers — unionized workers in particular — to figure out which hotels to kick ICE out of.

Can you speak more about your strategy of going on the offensive? Because a lot of people right now are trying to figure out how we can stop ICE. And what we’ve seen, beyond the important local defense and know-your-rights work, is mostly a lot of one-off protests or vague calls online to boycott companies. What you’re doing seems different.

I think about it as leverage and power: looking everywhere ordinary people have leverage and seeing where we can pull those levers.

Under a functioning democracy, you play the game of public opinion. If you convince the majority, then you can get legislation or win an election. But what we’re living under right now is not a democracy. In many ways, the feedback loop from public opinion to outcomes has been broken for a long time. It’s broken because of money in politics, because of the setup of our Senate, because of gerrymandering. And now they might just try to steal the election outright.

Public opinion still matters. It’s important that we have majorities on our side. But we’re fooling ourselves if we think public opinion alone will translate into victories, or that the midterms and 2028 will be normal elections.

A lot of establishment advocacy groups seem to be hoping we’ll show America that Trump is really bad, then in the midterms, we’ll take back power — a rerun of 2018 to 2020. I don’t think that’s accurate: just look at what Trump is doing now and how similar it is to how authoritarians in other countries have grabbed power.

So you have to switch from purely persuasion campaigns to the logic of noncooperation. You have to look at the ways ordinary people are directly upholding a regime’s ability to logistically function: where the money flows but also how they eat, how they sleep, who is doing the literal work enabling everything to operate.

Corporations aren’t the only method of looking at that. There are many. Local governments are a piece. But I do think corporations are a really key one, particularly corporations that the public has a lot of access to and influence over.

A lot of the companies collaborating with ICE are shadowy and operating in the background. But there are also companies like hotels — places we all book, sleep at, and spend money at — that we can actually shift, because we have leverage over them. That’s the logic behind corporate campaigning: identifying the places where ordinary people are directly enabling Trump’s regime to function.

When you look at it that way, there are dozens and dozens of little buttons you can start to push. We’ve been brainstorming a lot of other ones, too. For example: ICE agents drive around on the roads — could we get the city government to do construction on the highway entrances in or out of the Whipple Building? Things like that. The question is: What are the concrete ways they’re moving around, and how do you put yourself in the way using every nonviolent lever you have access to?

We zeroed in on hotels because we wanted to pick something that anyone, anywhere can immediately recognize: “There’s a Hilton near me. I could book a reservation and cancel it. I could leave a bad review on Booking.com.” You want to pick campaigns that everyone has power over, because our strength comes from involving large numbers of ordinary people. If it’s just the same activists who have been doing this for years, we can’t win.

Can you speak a little bit more to how you see the question of winnability as important for this? Because there’s a tension: if our only criteria for choosing targets is going after those that are most central to ICE’s functioning, you would start with the hardest targets: Palantir and Amazon.

But while it’s important to educate people about their role, it’s not clear to me that we can start there with our campaigns, because Palantir and Amazon will likely be the last two companies to break from the administration, precisely because they’re so deeply tied to ICE.

Winnability is key. When you’re organizing a population against dictatorship, it’s important to understand what the main emotional barriers are that stand in people’s way. In a lot of countries, that ends up being fear. I look a lot to Otpor in Serbia as an example: they identified fear as the main barrier and said, “What’s the antidote to fear? The antidote to fear is humor. We’re going to be funny in all of our actions so that people aren’t scared.” It was great.

I don’t think the main barrier in the US is fear. It’s skepticism. Most people don’t believe in our ability to change things. So one of the most important things for organizers right now is to pick campaigns that are ambitious, tangible, and winnable — wins that aren’t so small they feel meaningless but are still actually achievable. Because one of the biggest things we need to prove to ordinary people right now is that we really do have power over how the government operates, and over what happens in our society.

Winnability is always important, but it’s particularly important in the United States at this moment. That’s part of why we were picking hotels and Hilton: Hilton’s business model makes us directly relevant to how they make money in a way that’s really helpful for applying pressure. Similarly, this was true of the Disney+ subscription campaign around Jimmy Kimmel and the Tesla Takedown. It’s about identifying where there’s direct leverage — where we can interfere with how they make money in ways that can significantly damage their brand.

And I agree about Amazon and Palantir. I don’t think it’s bad to tell people about them. But I do think there’s a danger of overwhelming a lot of people right now. So many people tell us, “I don’t know where I’m supposed to shop. I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. Any interaction I have is bad.” That can be paralyzing. It doesn’t move people into action, and it doesn’t get people into organized formations. We need to build and deepen our momentum.

It’s much more effective to say, “Let’s go after one or a few targets at a time. Let’s actually knock them down, then move on to the next ones,” instead of, “Here’s a list of fifty companies you shouldn’t shop at and fifty things you have to feel guilty about doing as you go about your everyday life.”

I think the first step is to go after companies that ICE is physically interacting with, because that’s easier for someone who’s not on their phone all the time following politics to understand and see. That means hotels, car rental companies, and places that allow ICE to stage in their parking lot or directly enter their workplaces — which concretely tends to mean Hilton, Enterprise, and Home Depot. Those targets feel more clear and urgent to ordinary people than companies that are financially supporting ICE through contracts (or that have so far refused to take a public stand against ICE).

For each of those three companies, the demands are clear: stop housing them, stop renting them cars, stop letting them stage from your locations, and stop letting ICE into your workplaces.

And some of this is moving. There have been a lot of protests at Target in Minneapolis, which makes sense because the company is based in our city. There’s a meeting with Target’s CEO that I believe is happening this week about Target becoming a Fourth Amendment workplace, which would make it much harder for ICE to enter. That could be really great and a big step forward.

I agree it’s crucial to have a few winnable but ambitious campaigns like that. Beyond those three targets — Hilton, Enterprise, and Home Depot — do you think there’s anything else organizers could be doing to pressure other companies?

One really important and basic step folks can take immediately in their towns is to demand that every business, including small businesses, refuse to let ICE into their workplace. One fantastic element of neighborhood organizing becoming more offensive in Minneapolis is that twice this week, when I was sitting in different coffee shops, someone came in and asked the coffee shop to become a Fourth Amendment workplace and put up a sign on their door about closing on January 23 and never allowing in ICE.

When ICE agents show up to a Mexican restaurant in Minneapolis trying to get food and nose around,but they’re told to get the hell out by the owner and staff! They were told not to come back unless they have a Judicial warrant signed by a Judge! 👍 pic.twitter.com/s5R0vRDP0E

— Suzie rizzio (@Suzierizzo1) January 15, 2026

So many businesses I walk into in Minneapolis have that sign on the door — “ICE Is Not Allowed in Here” — which is fantastic. That’s not the same as a corporate target, because it’s often easier to move singularly owned businesses. But it’s a really important neighborhood-level tactic.

It seems like a big national organization like Indivisible or MoveOn could print a bunch of “ICE Is Not Allowed in Here” signs and ask all their supporters nationwide to go talk to every local business about posting the sign.

It’s not hard. It’s easy to walk into your coffee shop or corner store and say, “Can you put up the sign?” It’s within their rights, and it’s not a crazy ask for most business owners — it’s intuitive. It’s sort of the next step to the incredible mass mobilization work Indivisible has already been doing. They have a huge amount of leaders in every corner of this country, and here in the Twin Cities, they’ve been one of the groups helping drive key campaigns.

What are the other tactics you’ve seen be effective in Minneapolis?

For hotels, beyond noise demonstrations in the middle of the night, we’ve also been booking and canceling reservations, which we know is making them freak out about their bottom line. There’s a hotel downtown that we’ve booked out through May, which hopefully means ICE agents can’t book it because it’s full — and it also means the hotel is losing money.

We’re starting to review-bomb them on Booking.com. And we’re currently pursuing a strategy where we pressure the city council to revoke the liquor licenses of hotels that are housing ICE. That could be a really smart pressure point. Liquor licenses are revoked in stages, so if you revoke one or two, it can quickly spook the others into falling in line. Fortunately, we have a very sympathetic city council that is actively looking for ways to get in the way of what’s going on with ICE.

For local government, in Minneapolis and everywhere else, the key point is that hotels are licensed, and there’s a vast network of bureaucracy that exists for a city to function. This is the time to use that bureaucracy for good: find every permit, license, traffic ticket — anything that enables a business to function — and make it clear that right now ICE is murdering citizens of Minneapolis and terrorizing communities across the country. If a business is going to support that, then they shouldn’t get the support of the city.

Nonviolent tactics that waste a company’s time or money are really effective. For Enterprise, we’ve made and canceled car reservations, saying the roads are too icy. I’m also interested in slow-driving blockades of Enterprise locations: driving at two or three miles an hour with fifty cars surrounding an Enterprise so ICE physically can’t get in or out to book their cars. We haven’t tried that yet, but it could be an interesting tactic.

What can unions and nonprofits do to support going on the offensive against ICE?

I see a lot of established organizations unsure how to respond right now, and corporate campaigning is actually a very clear way to plug people in and build momentum. Sometimes it can even be digital. If all you have is a giant email list, tell everyone on that email list to book and cancel reservations at Hilton every single day. That’s a good use of people’s time and energy.

So my advice is: pick a strategic target — or a couple targets — and go all-in. If you have a base that can mobilize in person and do things like noise demonstrations or show up at an Enterprise location and cancel reservations, do that. If you don’t have a base that can show up in person but you have a list or a social media presence, there are digital tactics that are genuinely useful here, too. It’s a straightforward thing to join, and the more the merrier. But we need to get beyond one-off protests against companies — what we need is a focus on sustained pressure campaigns at strategic and winnable targets. Explaining the logic to people of focusing on breaking ICE’s pillars of support is crucial.

The union question is important. It’d be great if unions set up tip lines to get information about which locations ICE is using for hotels and car rentals. And I do think ULP [unfair labor practice] strikes are an interesting idea for workers in places that are getting targeted. This is a labor issue. Workers are in unsafe conditions right now: they’re getting grabbed at work, and they’re getting grabbed on their way to and from work. These are genuinely unsafe conditions, especially if you’re a person of color in Minneapolis — regardless of whether you’re a citizen or not. Logistics workers like truck drivers also have a huge amount of potential disruptive power to stop things like food deliveries to ICE’s staging centers.

For unions that are serious about protecting workers and democracy, there’s a worker-centric approach that’s extremely relevant right now, and it could interfere with corporations’ ability to uphold ICE.

Even if people aren’t in a union, they still have all sorts of individual and collective rights and leverage at work. Workers at a nonunion Hilton, for instance, can still put up pressure against ICE — it’s harder without support from an established union, but it’s doable. And this moment could be an opportunity for those in the labor movement who are seriously thinking about defeating authoritarianism and organizing the whole working class to say nationwide: Do you work at a Hilton, Enterprise, or Home Depot? Are you scared because of ICE? We’re going to support you to stay safe by fighting back. There are organizations like the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee that are eager to support any worker in these companies or others who want to fight back at work against ICE.

People are hungry to get involved. They are really scared, and they want to know their rights. But, above all, there’s a level of “I’m ready to do things” that feels really unparalleled, at least in Minneapolis. And it’s going to spread to the rest of the country as ICE expands, as people fully understand what’s happening, and as we keep up the momentum through wins along the way.