The Echoes of Ireland’s Bloody Sunday in Renee Good’s Murder

Like Renee Good’s murder in Minnesota, the Bloody Sunday massacre in Ireland was notable for both the blatancy of the crime, carried out in broad daylight, and the audacity of the lies pumped out from the highest levels of the state.

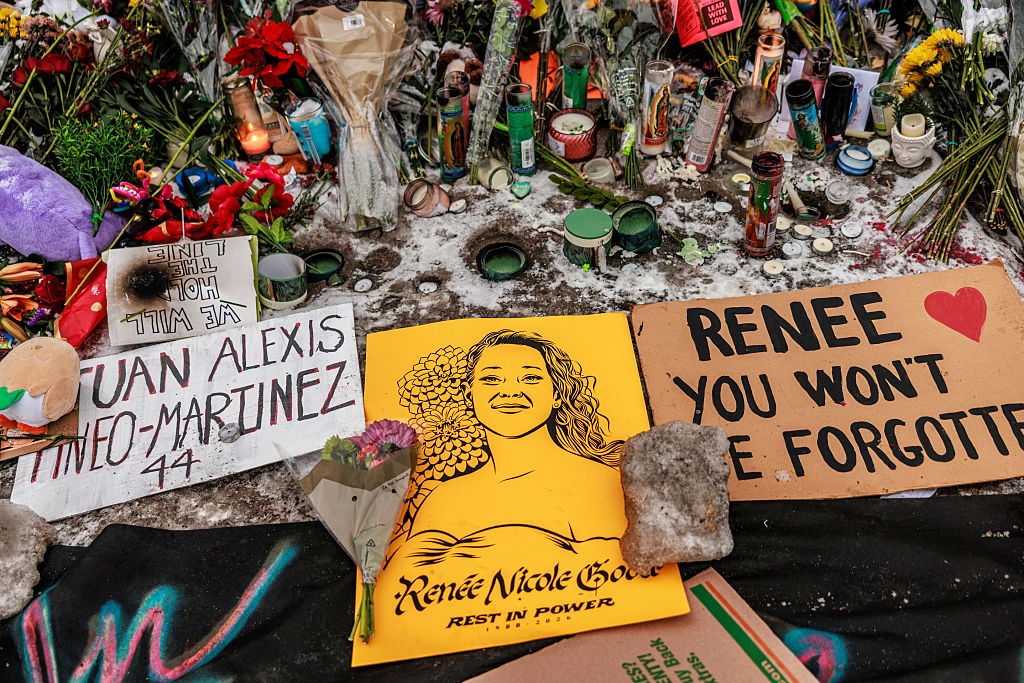

A makeshift memorial honoring Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on January 11, 2026. (Kerem Yucel / AFP via Getty Images)

Watching the murder of Renee Good in Minneapolis and the political developments that followed, it was impossible not to be reminded of the Bloody Sunday massacre in Derry. The British Army killed thirteen civilians on that day in 1972; a fourteenth victim later died of his wounds. We are still living with the consequences of the massacre.

The first parallel is the transparency of the crime, which in both cases was carried out in broad daylight. It wasn’t so easy to record events on a camera at the time of Bloody Sunday, but there were thousands of eyewitnesses in Derry that day, including representatives of the international media.

The second parallel concerns the audacity of the lies pumped out from the highest levels of the state. Trump administration officials pretended to believe that Good’s killer acted in self-defense, fearing for his life, just as British government ministers pretended to believe that the paratroopers had only pulled the trigger after coming under intense fire.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the authorities moved quickly to arrange a legal cover-up. In Minnesota, the FBI seized control of the investigation, with Kristi Noem falsely claiming that local law enforcement had no jurisdiction. In Derry, the government of Edward Heath brought in Lord John Widgery, Britain’s most eminent judge, to apply a thick coat of whitewash and exonerate the killers.

More than half a century later, the shameless mendacity of Widgery’s report is still enough to take one’s breath away. He ignored a mountain of evidence that refuted the army’s version of events. If Trump’s sock puppet Kash Patel is allowed to direct the investigation of Good’s murder, no doubt he will supervise the production of some equally brazen falsehoods, although his officers may not be able to match Widgery’s talent for rhetorical sophistry.

Provocation Before Bloodshed

There are also striking similarities of wider political context. In both cases, the authorities were deploying squads of armed men in a bid to demoralize and intimidate communities that stood in the way of their plans. The self-styled security forces were deliberately generating insecurity through provocative, coat-trailing exercises of power.

In Derry, the British Army was operating on behalf of an illegitimate, exclusionary system of government that treated the nationalist minority as second-class citizens. In a private memorandum, the British military commander Ian Freeland accurately summed up what unionist politicians really meant when they asked why his troops hadn’t moved to impose “law and order” immediately after their arrival in August 1969: “Why didn’t the Army counter the resistance of the Roman Catholics behind their barricades by force of arms and reduce this minority to their original state of second-class citizenship?”

Freeland’s interlocutors didn’t have long to wait. Well before the Irish Republican Army (IRA) had started targeting British soldiers, those soldiers were barging their way into nationalist areas, saturating neighborhoods in tear gas, and vandalizing people’s homes. They perjured themselves in court to secure convictions of young people on bogus charges of rioting.

Unionist leaders kept on demanding heavier doses of repression, culminating in the internment of suspects without trial from August 1971. The Bloody Sunday march was a protest against the internment regime. It was also an attempt by the march organizers to offer an alternative to the IRA’s campaign of guerrilla warfare as a way of resisting an unjust system. The British state managed to convince thousands of young nationalists that taking up arms against it was the only viable strategy.

In much the same way, the Trump team has mobilized Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in cities that are overwhelmingly hostile to the presence of its agents. It wants to generate fear and manufacture scenes of chaos that can be used to justify escalating repression.

Trump and his allies claim to be upholding legality while flaunting their contempt for the law — most recently by refusing to allow Rep. Ilhan Omar and two other Minnesota representatives access to the local ICE facility, in explicit defiance of an order from a federal judge. They accuse Good of obstructing masked, trigger-happy goons who won’t identify themselves, as if that were a crime worthy of execution in itself (“stalking,” no less).

Omar’s involvement points to another echo of Bloody Sunday. Just as Omar has become a hate figure for the US right, the left-wing MP Bernadette Devlin faced a virulent backlash from British conservatives after she was elected on a civil rights platform in 1969. When the British home secretary Reginald Maudling lied about the Derry massacre in the House of Commons, Devlin punched him. The British media expressed far more outrage about Devlin’s punch than it did about the shootings in Derry.

Political Competence

There are two important differences between the situation in the North of Ireland in the early 1970s and the situation in the United States today. First of all, there is no equivalent of the IRA waiting in the wings, for all the lurid rhetoric of the Trump administration about “violent left-wing networks” and its efforts to present “Antifa” as a terrorist organization rather than a loose political subculture.

It was possible for the IRA to launch a full-blown insurgency against the state because of a very particular set of circumstances, circumstances that do not exist in the contemporary United States. At this point, it seems far-fetched to imagine a much smaller organization in the mold of the Weather Underground or West Germany’s Red Army Faction entering the stage and leading the struggle against Trumpism down a bloody dead end.

On the other side of the political barricades, the government of Edward Heath and the civil servants who worked for it had a much better sense of statecraft than Trump and his associates, having had to deal with several anti-colonial uprisings in the postwar decades. In the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, Heath belatedly decided that it was no longer viable to prop up the unionist government in Belfast and imposed direct rule from London instead.

He soon unveiled a reform initiative that was designed to bring nationalists who were opposed to the IRA campaign back inside the political tent. Heath’s move came too late to stop the IRA from achieving a critical mass of support, but it was enough to keep that support within limits. Although the state forces continued to kill civilians after Bloody Sunday, their violence was more selective and more attuned to the need for plausible deniability.

The Trump team shows no sign of being able to perform that kind of political footwork. From Trump himself to Noem and J. D. Vance, the leading figures in this administration are impulsive, inexperienced, and strikingly immature. If they had been in charge of the British state in the 1970s, there would have been several more Bloody Sundays, and the time-hallowed United Kingdom would probably be a fading memory by now.

Nor is it simply a question of the individuals directing the respective state machines. British governments always had to be mindful of the international context. While the United States was London’s Cold War ally and its presidents were usually sympathetic to the British position in Ireland, there was always an Irish American political lobby in Washington that could be activated if Britain went too far.

There is no foreign power standing over the Trump administration, ready to apply pressure to bring it to heel. That sense of impunity is part of what makes the current moment in American politics extraordinarily dangerous. The shrill, bloodthirsty rhetoric of Vance and Noem over the past week may contribute to a decisive Republican defeat in the midterm elections later this year. But how much damage will they have already done by that point?