China Came Late to Capitalism but Early to Its Pathologies

In China, the number of single-person households has increased along with rates of loneliness. In this respect, China is not unique. It is simply suffering from the same social dislocation affecting all advanced capitalist states.

Job seekers and recruiters at a job fair in a shopping mall in Beijing, China, on November 18, 2025. (Andrea Verdelli / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Is China just another case of modern industrial development? It is tempting to talk about the country’s economic and social transformation in the context of “late industrialization” in the West Pacific. After all, China’s miraculous ascent to the summit of the manufactured goods trade over the last two decades was preceded by other growth “miracles.” Japan, Korea, and Taiwan (as well as some smaller southeast asian states) all seem to have created similar paths to export-led growth in which industrial policies created capital-intensive and high-tech manufacturing sectors that displaced their European and American competitors in global value chains. China could just be the latest, most spectacularly successful, “developmental state.”

This is plausible. But a few things sow doubt. One thing that stands out is the genuinely “hybrid” nature of China’s economy, where a one-party state socialism and a vast system of investment programs and subsidies enable hyper-intensive competition between firms and regions that drives both innovation and lower prices and costs. In other words, both the degree of capital coercion and the severity of consumer market forces distinguish it from its predecessors in the region.

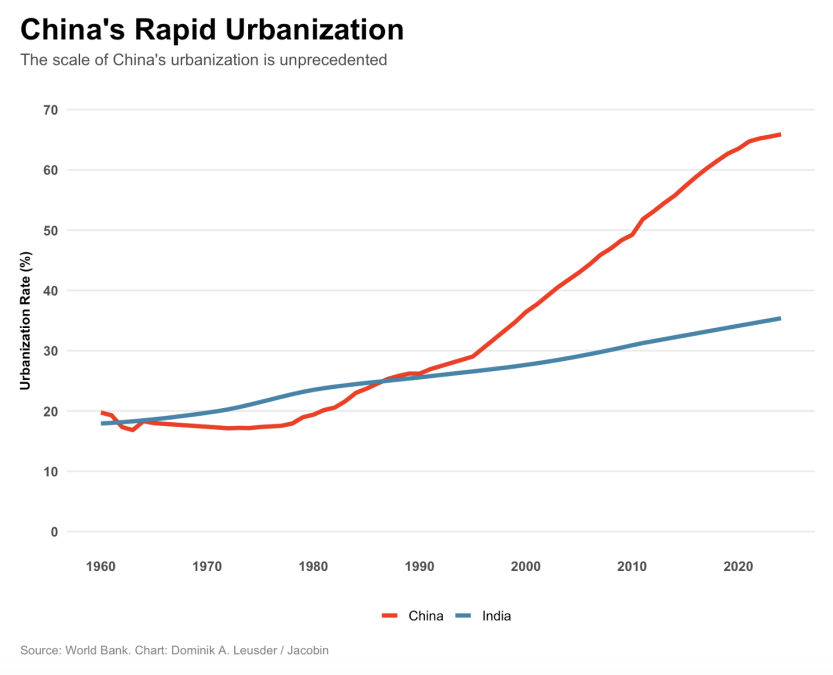

The scale of development, too, is different. It cannot entirely be written off as a reflection of China’s natural endowments. For one, past a certain point quantity can become quality. A country’s large labor pool, for instance, can enable labor-intensive manufacturing and create economies in domestic markets before upgrading to capital- and skill-intensive sectors. But size doesn’t guarantee anything. India entered the 1980s with higher rates of urbanization but has since been left in the dust as its industrial development stalled and is now showing signs of prematurely reversing (Figure 1).

By contrast, China’s urbanization is arguably the single most dramatic process of material and social transformation of the postwar era. Over the course of three decades, around half a billion people migrated into new cities, where 90 percent of all currently inhabited housing was built since the 1980s. This process also accounted for most of the country’s carbon emissions, with one estimate attributing 74 percent of the growth in household consumption–related emissions to urbanization. The grand infrastructure projects and material culture of these cities have become a source of envy.

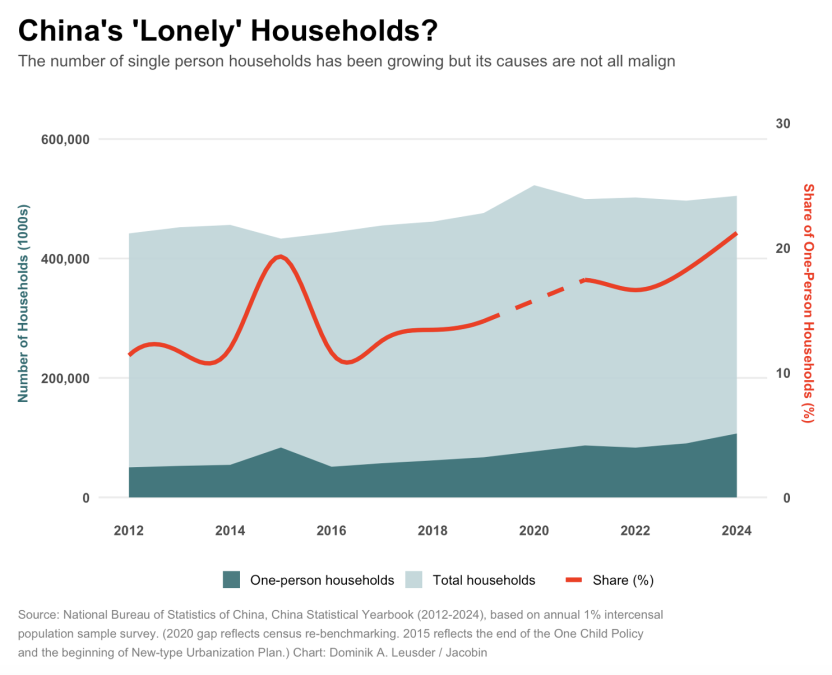

But transformations on this scale always create the conditions for new social crises. One trend that has caught attention recently is the “miniaturization” of Chinese households. The number of households with single inhabitants has grown markedly since 2012, rising to 107 million, or over 21 percent, of all households nationally in 2024 (Figure 2). A 2020 national census paints a more urgent picture, registering around 125 million people living alone.

This development has raised concerns over loneliness. A few young developers responded by creating an app named “Are You Dead?”, where users failing to manually “check in” for two consecutive days will trigger the app to alert their emergency contact. Though little more than a social experiment, it reflects anxieties very familiar to other industrial societies as they approach or experience economic maturity: mass loneliness and alienation and rising social cleavages.

In China as elsewhere, these trends develop in concert with slowing growth and social mobility amid rising inequality and precarity. And in China as elsewhere, it is young people in urban areas who are the worst affected. The generational buzzwords like tang ping (“lying flat”) or bailan (“let it rot”) find their equivalents in sampo or n-po in Korea, or satori or hikikomori in Japan. To speak of the “loneliness epidemic” in the West is to risk lapsing into cliché. All of these express the same disillusionment with materialism in the face of economic stagnation.

Whatever the uniqueness of its political economy, China seems no less prone to the pains of economic maturation. To the extent that the recent demographic data reflects a malign trend, they are part of a general pattern of social outcomes seen across advanced economies.

During the Biden administration, policy makers began talking about what they termed “K-shaped’’ economic recoveries in which different segments of the economy diverge after a recession, one growing, the other stagnating or falling. This talk had the effect of obscuring the fact that these simply entrench the already existing structure of “the dual economy.”

Within China, but also advanced capitalist states, a distinctive pattern is developing in which modern high-productivity sectors are flourishing, while low-productivity services or informal sectors stagnate and experience persistent underemployment and barriers to labor reallocation. The former are dominated by asset owners and capital holders (now also the highest income earners) who thrive amid asset price inflation, while the latter sectors comprise much of the wage-dependent population chafing under worsening cost-of-living pressures, exacerbated by the increasingly large consumption shares of the wealthy.

This inequality-driven bifurcation is in fact particularly pronounced in the successful East Asian trading economies, with the competitive high-tech manufacturing economies on top still benefitting from more exploitable and wage-repressed labor. What’s more, the owners of large export-driven businesses benefit from the persistent currency weakness, which further undermines the spending power of the average household.

If anything, the “late industrializers” have developed this particular kind of dysfunction more quickly and severely than many Western counterparts (the United States’ festering social crisis is in a category of its own). Among other things, this “premature economic maturation” is likely a function of lower levels of social protection and of the fact that “late” development benefits from newer technologies, ideas, institutions, deeper global markets, etc.

But these latent crises are also undeniably a sign of great success. The more dramatic and speedy the capitalist development, the greater the severity of the social dislocations that generate these dual-economy patterns.

The trend of single households in China is a perfect illustration of said patterns. While some emphasize the role of lower fertility rates and changing attitudes toward marriage and divorce, recent empirical research locates the main causes elsewhere. The two key insights about one-person households are that they are predominantly the rural old and the urban young, and that their distribution is curvilinear with regards to local development (that is, people living alone are concentrated in both the least developed and the most developed prefectures, less so in the “middle”).

This implies that the trend is largely due to the compositional effects of the rural-urban mass migration that attended China’s great urbanization push. Put simply, the young moved to the big city and left behind empty nests in the countryside. Overwhelmingly, these young people found better jobs, educational attainment, and social mobility. In this context, living alone was more often about the new-found ability to put off starting a family, which benefitted women in particular.

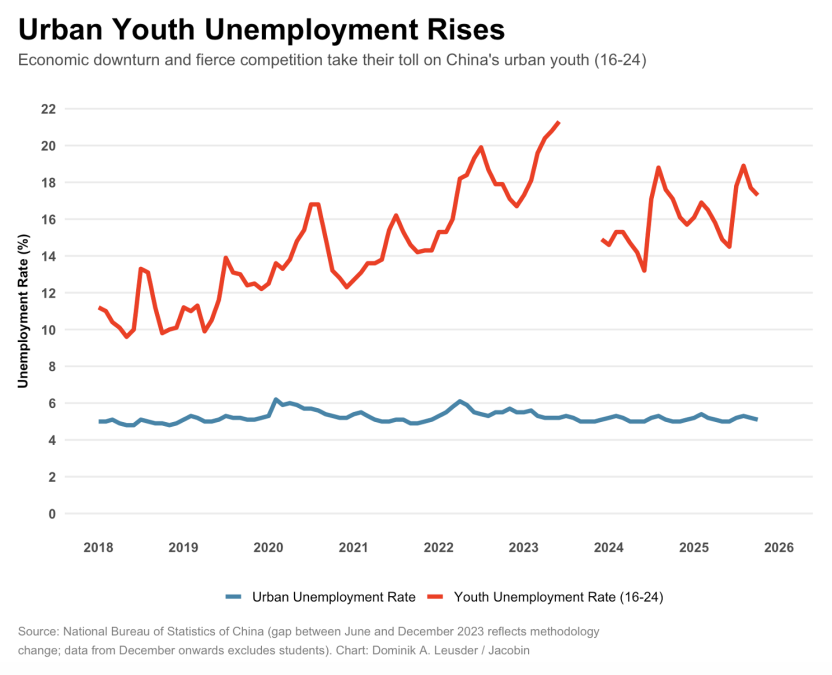

Then, amid the economic downturn from 2020 onward, as opportunities for social advancements evaporate, many young people get stuck. Those who just get by with several jobs are lucky: the youth unemployment rate diverged sharply from the headline figure, and it is probably not a good sign that the government discontinued the relevant data series after it reached just under 22 per cent in 2018 (Figure3). For comparison, the current rates in Italy and Germany are around 19 percent and 7 per cent respectively. On top of that, young people in more developed prefectures see the financial benefits of higher educational attainment eaten up by higher housing costs.

This is because, despite an epic real estate crash, many young people still pay 30–50 percent of their monthly income on rent. Meanwhile, price-to-income ratios remain among the world’s highest, implying at least 30 years but in big cities up to 122 years worth of full income to be able to purchase a 90-square-meter apartment. As in the West, the top two income deciles own the majority of assets (~63 per cent by a 2020 estimate) and housing assets play an outsized role.

Urban living remains cramped and unsuited to long-term cohabitation, let alone family planning. Recent commentary in the official political theory journal of the Communist Party of China, Qiushi, suggests that 40 percent of households live with less than 30 square meters, while 7 per cent less with less than 20. In this environment, the insecurity and lack of belonging as migrants affect women in particular, which is why fewer women than men live alone in the more developed prefectures.

Much of this seems awfully familiar. These are the commonplace dysfunctions of economic “maturity” attained through “uneven and combined” capitalist development in the neoliberal era. And while China’s domestic policies and mode of integration into the global economy were decidedly not neoliberal, it is the structure of global inequality — driven principally by the mobility of short-term financial flows globally and the oligarchic aggrandizement of wealth that feeds those flows (aka neoliberalism) — that allows China’s elites to maintain the domestic patterns of inequality that create the “dual-economy” dysfunction.

And its current trajectory is set to worsen this situation, with net exports contributing over 50 percent of annual GDP growth and a deeply undervalued currency worsening this reliance at the expense of household purchasing power.

But while in Western Europe, North America, or Japan, these malign trends come on the heels of years of stagnation and growing political dysfunction, in China they follow the largest and fastest improvement in living standards for the greatest number of people in world history. There is no contradiction here. It is simply the price of being late, which is part of what explains the extent of China’s success. So, is China just another “case” or is it exceptional? All signs point to both.

The good news, then, is that China might be becoming more normal. The bad news is “normal” is no longer anything to smile about.