The Case for America With Some Chinese Characteristics

China and the US are currently locked in a dangerous rivalry, but things don’t have to be this way. We spoke to Dan Wang, the author of a new book which argues the two nations should learn from one another.

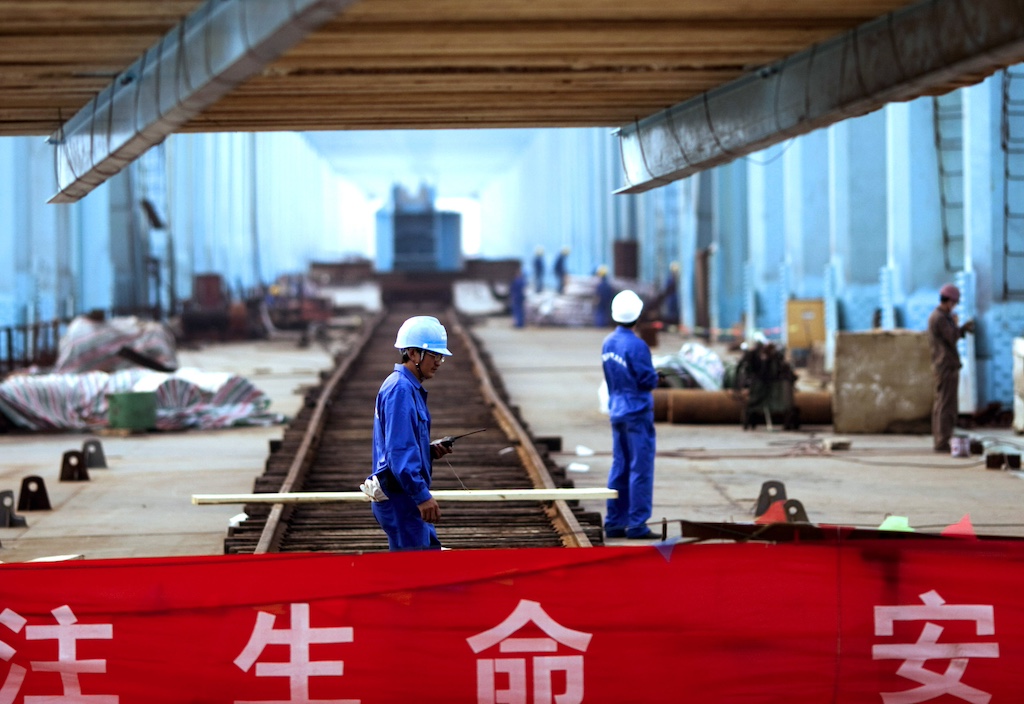

Construction workers building the high-speed rail network in Nanjing, China. (Benjamin Lowy / Getty Images)

- Interview by

- Daniel Cheng

The United States is by most metrics the richest country in human history, yet it fails at performing tasks that nations with a fraction of its GDP excel at. The quality of roads, trains, and other forms of infrastructure are poor across the country, and Washington’s political system is gridlocked by parties without any vision for how to enact change.

In his recently published book, Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, Dan Wang offers a critical look at the People’s Republic and asks what the United States can learn from it. While he makes no attempt to look away from China’s suppression of civil liberties, he acknowledges that the United States could learn a great deal from the Communist Party’s ability to rebuild society in a way that improves the living standards of the majority. Wang spoke to Jacobin about the origins of what he calls China’s “engineering state” and why the United States, despite having many other advantages, is held back by a society run by and for lawyers.

The main argument of your book revolves around China being an engineering state and secondarily the US being a lawyer society. Can you just explain what these terms mean?

I spent six years living in China from 2017 to 2023 and the major events of that time included [Donald] Trump’s first trade war, Xi Jinping’s darkening political ambitions, and Zero COVID, which I lived through. Thinking about these two countries at a time when they are being confrontational with each other, I decided that twentieth-century labels like socialist, neoliberal, or democratic weren’t very useful for explaining the present moment.

So I try to come up with a new framework. I call China an engineering state because since the 1980s, Deng Xiaoping has really tried to promote a lot of engineers into the Politburo and at various points some of China’s most senior leaders have had degrees in engineering. And the issue with engineers is that they tend to treat construction as the solution to every problem. That’s why you have so many homes and coal plants and solar and wind and transmission lines and bridges and highways everywhere. A lot of my book is also about how the Politburo can’t stop themselves from just being physical engineers.

They’re also fundamentally social engineers. I spent a lot of time thinking about the One-child Policy, Zero COVID, and the ways the Communist Party tries to Sinicize China’s ethno-religious minorities. The engineering state involves both physical engineering as well as engineers of the soul. And I contrast that with the lawyerly society.

The issue with lawyers is that they block nearly everything, good and bad. So you don’t have stupid ideas like the One-child Policy, but you also don’t really have functional infrastructure or any homes across America. That’s the dichotomy I offer as a kind of playful device to get us beyond terms like socialist or neoliberal to understand these two countries.

Physical Engineering and Social Engineering

It seems like in your view China’s physical engineering is mostly positive and the social engineering aspect is mostly negative. You recount all the downsides of social engineering very well in this book, with all the horrors of the One-child Policy and Zero COVID. Do you think these two forms of engineering have to go together? Can China or other societies take all the great aspects of the physical engineering without the social engineering?

I think the short answer is “probably,” but the slightly-longer-than-one-word answer is “maybe not.” So the “probably” is that I’m speaking to you now from Copenhagen. I spent the past month in what one might call a borderline socialist paradise where things work really well. Every few years they build a new subway line. Every other year, they need to build a new bridge. These costs aren’t excessive. This is infrastructure that goes where it needs to go, and the city feels highly functional. One of the things I believe is that the US shouldn’t try to emulate China wholesale. There are many other countries that it could draw on as a better model, like Denmark. If the US could get construction costs on the level of Japan or Spain, that would be amazing. You don’t have to go full China in order to build a lot.

Now, the reason I think “maybe not” is that these great powers aren’t very good at acting rationally. Edward Luttwak coined this term “great power autism” by which he meant if you’re a superpower, you tend to really ignore a lot of things and focus on a few things. I think it’s not an accident that these two countries really are hyperspecialized in the sense that the US is mostly run by lawyers and China is mostly run by engineers. So could this happen in principle? Sure. But I think this is probably not going to work out.

Something I fully agree with you on is that I think it is definitely the case that being physical engineers is mostly good. To have a lot of construction of necessary infrastructure and homes and power and manufacturing is mostly good. There are certainly problems with a ton of waste, financial problems created from excessive construction, and carbon emissions to produce cement for bridges to nowhere. But I think that it is pretty good to have functional infrastructure, smoothly running cities, and a very robust manufacturing base. The tragedy of China is that the engineers can’t stop themselves at only physical engineering because, sooner or later, they view the population as just another building material to be molded or torn apart.

Domestic Pessimism Despite High-Tech Success

You talk a lot about how the Chinese engineering state has made a lot of significant progress in high-tech manufacturing with industrial policies like Made in China 2025. But despite this, sentiments within China are growing increasingly pessimistic. You describe the phenomena of rùn, young Chinese fleeing to better futures. Meanwhil, in the US, we see people sharing all these videos of robots dancing, electric vehicles, and amazing high-speed rail. What do you think about the gains of all this high-tech manufacturing and its relationship to the general population? And why does there seem to be a disconnect between all this technological progress and the general sentiment of the population?

High-tech manufacturing creates a tremendous amount of political prestige for the government, but it hardly makes life better for most people. Something like semiconductor manufacturing or aviation is not going to employ more than a few hundred thousand people in each sector. It’s a little bit different with electric vehicles because automotive manufacturing would employ many more. But generally, the story of high-tech both in China as well as in Silicon Valley is that these tend to create some degree of national power. They strengthen the American government as well as the Chinese government; they create some degree of political prestige for the governments; they create fabulous wealth for a few lucky people; but generally high-tech in neither Silicon Valley nor China has trickled down in terms of very substantial job creation or spreading the wealth among the people.

However, that’s not a reason to not pursue these sorts of things. If you are a resident of any big first-tier Chinese city today, your life would be somewhat better than the lives of people in third-tier cities. But a lot of people are pretty tired of Chinese work culture. Nine-nine-six [9am to 9pm, six days a week] is not totally real, but it’s pretty real.

If you’re working for a state-owned enterprise, the conditions are not that much fun because there’s so much politics there. If you’re working for one of these big internet platforms, nine-nine-six is much more real. And if you’re working as a clerk at a bubble tea shop or as a barista in a café, you’re maybe having more fun there, but your income is not astonishing. This leads to a lot of people feeling increasingly disconnected from the top ranks of a leadership that is increasingly gerontocratic. People are also increasingly disconnected from the major prestige projects that the Politburo likes and that the population doesn’t feel are tangibly connected to them.

Your book highlights the differences between the engineering state and the lawyerly society, but at the same time, you say that American and Chinese people are similar. Given the tensions between the US and China, what do you see as the future of US-China relations? Are you optimistic or pessimistic?

Here is where we have to wonder where these framings of optimism and pessimism go. If we are optimistic about the US and China becoming partners in some way, maybe that’s generally pessimistic for the world because we can expect them to bully more regional powers like the Europeans, the Japanese, and the Taiwanese. Maybe the worst thing for these nations would be for Donald Trump and Xi Jinping to buddy up and threaten the rest of the world.

I think one of the things that we have to first confront is that the worst thing in the world would be for these two superpowers to meet in a confrontation. World War I had many millions of deaths. Conservative estimates put the number of casualties caused by World War II at something close to fifty million. And we certainly don’t want another war, which would be orders of magnitude worse.

I think one of the great tasks that is in everyone’s interest, even for those who think that China doesn’t really affect them, is to avoid that sort of global confrontation. Short of that, I think the options out there are some sort of partnership between them. I think that’s quite unlikely even though Donald Trump is the most pro-China member of the White House.

Or are they going to be able to engage in some sort of simmering competition that never boils over? Maybe there is some way in which we acknowledge that these two countries have very deep fundamental frictions and problems with each other. There are going to be frictions and that these frictions will need to be managed in some way.

Do you think there’s a way in which the US and China learn to get along, but by creating regional imperial spheres of influence? For example, the US deciding to not get involved in the South China Sea or Taiwan and letting Beijing ride roughshod over these areas?

I think a lot of the US political establishment is pretty intent on maintaining its presence in the Asia-Pacific. The US has treaty allies in East and South Asia. Many East Asian countries really want to keep the US on their side. I think that even if China achieves a kind of narrow objective of only dominating the South China Sea and having the rest of the leaders of Asia regularly go to Beijing to kowtow for the emperor’s pleasure, that is still a pretty undesirable scenario for the US. I think it’s legitimate for the US to work in concert with these other Southeast Asian and East Asian countries to really try to make sure that Beijing doesn’t dominate.

China is nominally a communist country that supports workers, but you’ve also described it as one of the most right-wing regimes in the world. To what extent do you think it might be accurate or appropriate to define China as left-wing or even socialist?

I think that China is certainly a Leninist regime that is ruled by a cadre of paranoiacs who view their task as dragging the population into some form of modernity. But I think there are some ways in which China is just a classically right-wing regime.

Xi Jinping has been on record saying we can’t give handouts to our citizens because welfarism would only make people lazy, which makes him sound like Ronald Reagan. This is a state that enforces traditional gender roles in which men have to be macho and women have to bear their children. This is an ethnostate in which, you know, even if you’re Chinese but not Han, you could have a pretty difficult time living in China. This is a country that hardly allows immigration.

If you’re north of sixty, it becomes increasingly difficult for foreigners to stay in the country. There are some ways in which China is socialist. If we take a look at the means of production, quite a lot of important upstream industries are state-owned, namely sectors like energy, telecoms, finance, and aviation. But I think it is difficult to label this country Marxist, in part because it arrests union organizers and tries to disrupt Marxist reading groups.

We should be fully comfortable with calling it Leninist, but it is difficult to call it socialist given how little economic redistribution it actually engages in. My short tagline is that China is a Leninist technocracy with grand-opera characteristics: a lot of these party congresses feel like Wagnerian operas where you have less noise but greater downfalls. It feels mostly right-wing to me.

You mentioned all these negative right-wing aspects of the Chinese government. For our readers who are predominantly leftists or socialists, is there anything that you think they should learn from China?

I think that China provides a good operating model of abundance. Not great, but a good operating model of abundance. I quite like the recent review in Jacobin of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book. Abundance does need a muscular government able to build and overcome some aspects of the bureaucracy. You cannot have an inactive government to build something like subway lines or train lines. That will always entail some degree of rationalist engineering thought as well as some degree of displacement. The only question is how to balance these sorts of things.

I think you cannot decarbonize the economy without doing many of the same things because decarbonizing the economy requires a tremendous buildout of solar, wind, and transmission lines and all of these require quite a lot of land. And so we cannot achieve a lot of these goals of abundance without having a muscular state.

But again, China is a good operating model of abundance, not a great one, because it overstates the discretion of the state. I think what we need is to just reach European levels of cost. We don’t need to go full-on China, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t look at China to learn a few things.

One more thing to add on to that is that having a robust manufacturing base was really, really good in the early days of the pandemic. Western producers struggled to make things as simple as cotton masks and cotton swabs in sufficient quantities. This is something that the Chinese have not struggled to do. For all the fearsomeness of the American military-industrial complex, they have not been able to produce munitions after giving a lot to Ukraine. Every class of naval ships by the US Navy is behind schedule by months or years. Something in America has deeply rusted between both the government and the corporate sector. And this is where, in terms of building, engineers are better.