The Warner-Netflix Deal Is Worse Than You Think

Netflix is after far more than the Warner Bros. movie studio — it wants to destroy cinema as we know it.

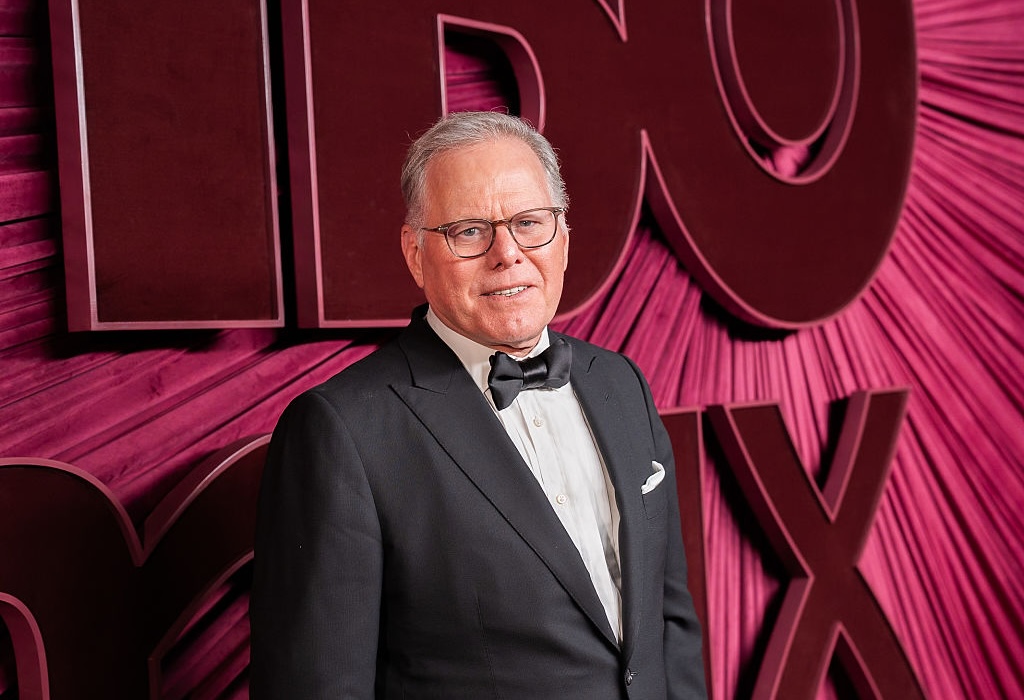

When Discovery merged with Warner back in 2022, CEO David Zaslav planned major cutbacks to Turner Classic Movies, firing 80 percent of the staff and likely planning deeper cuts in the future. (David Jon / Getty Images for HBO Max)

The news that Netflix would be acquiring Warner Bros. for $82.7 billion dollars has been met with widespread concern among the entertainment industry as well as in Washington. Politicians on both sides of the aisle, from Elizabeth Warren to Mike Lee, have expressed concern over the possible consolidation of two of the biggest movie and television conglomerates in the world.

Most of the anxiety is rightly focused on fears that the merger would result in outright monopolization leading to thousands of lost jobs, a reduction in the number of movies and TV shows that get made, and a possible death blow to the already teetering movie theater business. And while all of those are likely outcomes of a merger, the damage from this deal could actually be even worse.

Some of the lesser-discussed aspects of Warner’s business are in jeopardy as a result of this deal, which could have a devastating effect on the world of cinema as a whole. In short, by buying Warner Bros. — which includes Home Box Office (HBO) as well — Netflix will also be purchasing a number of legacy projects that it has already spent years trying to destroy. If the merger is completed, Netflix will likely succeed in strangling key efforts at film conservation, jeopardizing the history and future of the art form.

Turner Classic Movies Is a Cultural Treasure — and It’s All but Certain to Die Under Netflix

In the terms of the deal, Netflix would be acquiring a newly formed Warner Bros. that primarily consists of Warner’s movie and TV studio, HBO, and the HBO Max streaming platform. The other major chunk of the company, cable networks like Discovery Channel and CNN, would be spun off to an independent company.

With one major exception: the cable channel Turner Classic Movies (TCM) is, in fact, included in the Warner Bros. side of the split. TCM is a treasure for film lovers, introducing young viewers to a thoughtfully programmed collection of classic films and forgotten greats.

This year alone, TCM programmed thoughtful tributes to stars who passed away, like Gene Hackman, Robert Redford, and Diane Keaton. Its Two for One series invited directors, actors, and top film critics to program a double feature, placing their classic library in conversation with the artists of today. TCM franchises like Noir Alley and Silent Sundays continue to spotlight incredible American films that were lost to time. The TCM Festival in April featured a tribute to VistaVision, a high-resolution film format introduced in 1954 but largely abandoned by the early 1960s, which also served as a testing ground for the projectors later used to screen new prints of this year’s acclaimed Leonardo DiCaprio film One Battle After Another, shot in the format. VistaVision, beloved for its impressive high-resolution imagery, is now undergoing a renaissance with recent critical favorites like The Brutalist and Yorgos Lanthimos’s Bugonia being shot on the format, as well as upcoming films like Greta Gerwig’s Narnia series and Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s Tom Cruise film.

It is also, most likely, not a very profitable enterprise. Movies playing on TCM have sharply limited commercial breaks and get low fees from cable providers, who must pay a certain amount to every channel for the rights to air it. What’s more, cable TV itself is in a death spiral — largely thanks to Netflix itself.

TCM has already been on the chopping block once. When Discovery merged with Warner back in 2022, CEO David Zaslav planned major cutbacks to the network, firing 80 percent of the staff and likely planning deeper cuts in the future. TCM was saved only by the intervention of acclaimed filmmakers Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Paul Thomas Anderson.

But having to rely on a CEO’s good graces is not a sustainable way forward for TCM, and things will only get worse with the changeover. Netflix is trying to kill the cable industry and likely has no interest in running a cable channel. If it keeps TCM at all, it will be as nothing but a brand — an icon for a section of Netflix showing old movies.

This is already how it works on HBO Max. Instead of TCM’s thoughtful curation, excellent supplemental content like interviews and introductions, and history-spanning commitment to surfacing lesser-seen films, TCM on HBO Max simply presents users with a haphazard dump of old movies, with no idea how to navigate it or what to look for. It focuses on headliners, classic movies like Citizen Kane and Singin’ in the Rain, which certainly are great films but only comprise one small part of TCM’s mission.

This would only get worse under Netflix’s vaunted algorithm. Instead of underseen classics — contextualized by filmmakers, professors, and critics — users would simply see what the algorithm wants them to see. In other words, something like Netflix’s current home page.

TCM is too important a resource to be left to the profit motive. It should be spun off as a nonprofit, absorbed by an organization like the American Film Institute, or simply nationalized. While there’s nothing quite like TCM, many countries have national cinema funds. Organizations like the National Center for Cinema and the Moving Image (CNC) in France, the British Film Institute in England, and Telefilm in Canada are tasked with both the preservation of old movies and the funding of new ones. A nationalized TCM could be the first step in creating the kind of organization that doesn’t just preserve old films but also gives crucial funding to artists shut out from the Hollywood studio system — a system that seems to be breaking down before our eyes.

Warner’s Vast Archive of Treasured Cinema Is Under Threat

As a century-old studio, Warner Bros. is responsible for the preservation and upkeep of thousands of movies, ranging from all-time classics to movies that have largely been lost to time. Studios keep nearly everything related to a film, from the original negative of the finished work to test prints and outtakes, even publicity stills.

There are major concerns about entrusting Netflix with these materials. For starters, while one would assume advances in digitization have helped film preservation, the opposite is actually true. Digital files degrade more quickly than physical film and are more endangered by environmental conditions like temperature, humidity, and other factors.

Additionally, a key part of film preservation is the restoration of old movies, an expensive and laborious process. Currently studios fund this work because they can release the restored movies in theaters for repertory screenings or sell it on Blu-ray or DVD. Netflix has no interest in either.

On the topic of movie theaters, Netflix CEO Ted Sarandos has made his opinions known. In the past, he’s called the communal experience of a movie theater “an outmoded idea.” While Netflix does send a few of its movies to a very limited number of theaters, Sarandos begrudgingly admitted Netflix was forced to do so in order “to do some qualification for the Oscars.”

The only value of a theatrical release for Netflix, then, is satisfying Academy Award requirements. That has meant small, token theatrical releases for 2025 Oscar contenders like Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein or Sundance hit Train Dreams. But Warner’s film preservation work over the last few years has included brand new 70mm prints of Boogie Nights and North by Northwest, both of which toured theaters around the country. There were 4K restorations of everything from classic Tom & Jerry cartoons to Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. And meanwhile, the Warner Archive DVD label released Blu-rays of a wide range of forgotten westerns, noirs, musicals, screwball comedies, and other old Hollywood movies. None of this work has any value to Netflix, where an older movie would simply be added to their massive sea of content and disappear just as quickly.

With both theatrical and physical media releases ruled out by Netflix ownership, a forgotten older movie, restored to its former glory, has almost no value to the company. As it is, Netflix barely has an interest in programming even popular old movies. The company went viral earlier this year when it was revealed that the earliest movie on the service was 1973’s The Sting. Why would they go to the expense and effort it takes to restore an old movie when it would simply disappear into their ocean of content?

We’ve seen an example of how this can play out after a major entertainment merger in the streaming age. When Disney acquired Twentieth Century Fox’s legendary film library in 2019, it promptly stopped allowing repertory cinemas to screen Fox’s classic movies. This meant that the enormous number of classic Twentieth Century Fox titles now under Disney control — rep mainstays like Alien, Planet of the Apes, The Sound of Music, Die Hard, Fight Club, and Home Alone — were simply taken out of circulation on the big screen for years, only recently returning.

At a time when one of the few genuinely exciting trends in the world of cinema is the growing popularity of repertory theaters screening old movies on film, taking a major library off the market would be yet another blow to the theater industry that Netflix is apparently keen to destroy entirely. As movie theaters have struggled with finding creative solutions to the problem of Hollywood’s substandard (and decreased) output, repertory cinema has been a rare bright spot. Theaters like Metrograph in New York, the New Beverly in Los Angeles, the Philadelphia Film Society (PFS) in Philadelphia, Coolidge Corner Theatre in Boston, and Music Box Theatre in Chicago have thrived as young cinephiles have flocked to see old movies on the silver screen. Recent rereleases of films ranging from Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (only in IMAX 70mm) to Jaws to Kill Bill have enthralled moviegoers. Even more important, studies show that the supposedly “YouTube-addled” Gen Alpha actually prefer the theater experience to streaming, despite what Sarandos might say about the communal experience of a movie theater being “outdated.”

Rather than trusting Netflix to be stewards of such an important piece of America’s artistic and cultural landscape, they should turn over control of the archive to an institution like the University of California, Los Angeles, which already does a great deal of film preservation, along with the rights to license movies for rep screenings and physical media releases, the way Warner itself has assumed control of a number of old studio libraries.

Physical Media Is the Antidote to Our Streaming Dystopia — and a Growing Part of Cinema Celebration

Speaking of DVDs and Blu-rays, one lesser-known side of Warner’s business is Studio Distribution Services (SDS), a DVD and Blu-ray production company that it owns half of along with Universal. SDS puts out all Warner Bros. and Universal movies on disc, so if you own the 4K physical releases of Sinners, One Battle After Another, or Oppenheimer, you own something SDS made.

It also works with a number of outside partners, making discs for independent studios like Neon (Parasite and Anora), Blumhouse (Get Out and Happy Death Day), and Shout Factory, a distributor that puts out special editions of older catalog movies ranging from Bullet to the Head to the Oscar-winning Spotlight to hundreds more.

Netflix, in essence, would be buying a 50 percent share of one of the biggest players in a business that it is actively trying to destroy. While the company made its mark by initially beating Blockbuster at its own game, renting DVDs in a far more user-friendly way than the old video behemoth, Netflix founder Reed Hastings was clear-eyed about his company’s ultimate goal: “We’re not in the DVD business. The only reason why we have these DVDs is to scale the customer base for what we ultimately want to do, which is streaming.”

Of the thousands of movies released by Netflix, only around ten have received a physical release. This makes sense when you consider its business model. Instead of getting a licensing fee from a onetime disc purchase, Netflix’s model ensures you send them money every month, regardless of whether you actually watch any of their movies or shows.

While physical media may not seem as important to the medium as film preservation or theatergoing, it’s every bit as vital in the streaming era. First, streamers like Netflix frequently shuffle what’s available on their service, whether due to rights deals, viewer interest, or the machinations of the algorithm. Only by buying a physical copy of a movie can one be assured they’ll always have the opportunity to watch said film.

Second, physical releases play a vital role in the life of the modern cinephile. As Hollywood releases fewer and fewer challenging movies, people who do not live in a big city might not have access to a theater like Metrograph or Music Box. However, thanks to the Criterion Collection, Vinegar Syndrome, and similar independent distributors, they’re guaranteed a steady stream of exciting and challenging catalog releases every week lovingly packaged and printed on a high-resolution disc. Criterion in particular has become the cherished custodian of a number of legacy films, directors, and movements vital to our culture.

It’s not just availability though — it’s a question of quality. While streaming technology is remarkable, the video quality still lags far behind what you get with a 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray disc. Limited bandwidth means the actual files that Netflix streams to you must be severely compressed, leading to lower-quality visuals. And for older movies, like the kind in Warner’s massive film library, Netflix removes the film grain and then adds a fake digital version back in since the real grain is unpredictable and inflates file sizes.

But just as importantly, we’ve learned over the last few years that streaming simply devalues art in the minds of most people. Just look at a company very similar to Netflix: Spotify. Spotify delivers millions of songs at a remarkably low price to the consumer who no longer needs to buy a CD or record to listen to music. But as a result, artists make mere cents off of each listen to one of their songs, while music fans have been trained to no longer think of albums as complete, connected works of art but rather song farms for playlists. Instead of walking over to your shelf to browse a collection of treasured vinyl records and CDs, you’re left only with the algorithm to guide your listening.

Playing Defense

Let’s be clear: the best outcome is no merger at all. Whether Netflix succeeds in acquiring Warner Bros. or the studio ultimately goes to a rival like Paramount Skydance, thousands of people will lose their jobs, fewer movies and TV shows will get made, and the ones that do get through will be even blander and more intellectual property (IP)–driven than ever before. Given that audiences seem to finally be rejecting safe but tepid franchises like Marvel and Disney’s animation remakes — even Wicked: For Good, a sequel to a massive hit from last year, has underperformed — Netflix’s acquisition of Warner Bros. would be a massive step backward at a time when the industry can least afford it.

But while it may not be possible to avert a merger, it is vital to at least limit the damage that will be done in the event of such a deal. It isn’t just the future of cinema at stake. A company like Netflix assuming control of a company like Warner Brothers also threatens the entire history of the art form.

Mostly, we tend to think of Hollywood as a business conglomerate, run by suits who are focused on creating slop that will appeal to the broadest audiences possible. And while that’s not entirely wrong, there’s a large group of people who work for film studios in roles that involve highlighting forgotten work, celebrating the history of cinema, or carving out space for genuinely exciting artists to practice their craft. TCM, Warner’s archivists, and the collectors and nerds who watch old movies all work together to protect the legacies of artists from the past.

This delicate system shouldn’t be destroyed by a tech company that wants nothing more than to get their hands on Warner IP like Harry Potter and Batman. And it shouldn’t be subjected to the whims of an economy that drives corporations toward dramatic mergers and major acquisitions in order to keep the stock price high. Cinema is a dirty and cynical business, but it’s also one of the most vital forms of American art of the last century. If we don’t set up a robust system of film preservation, freed of the whims of a market now turning against artists like never before, then we risk losing the entire history of the art form.