Norman Podhoretz Always Stood Out

Interacting with the neoconservative intellectual Norman Podhoretz, you felt desire. But it wasn’t a desire for ideas; it was a desire for being thought of as someone who was adept at ideas.

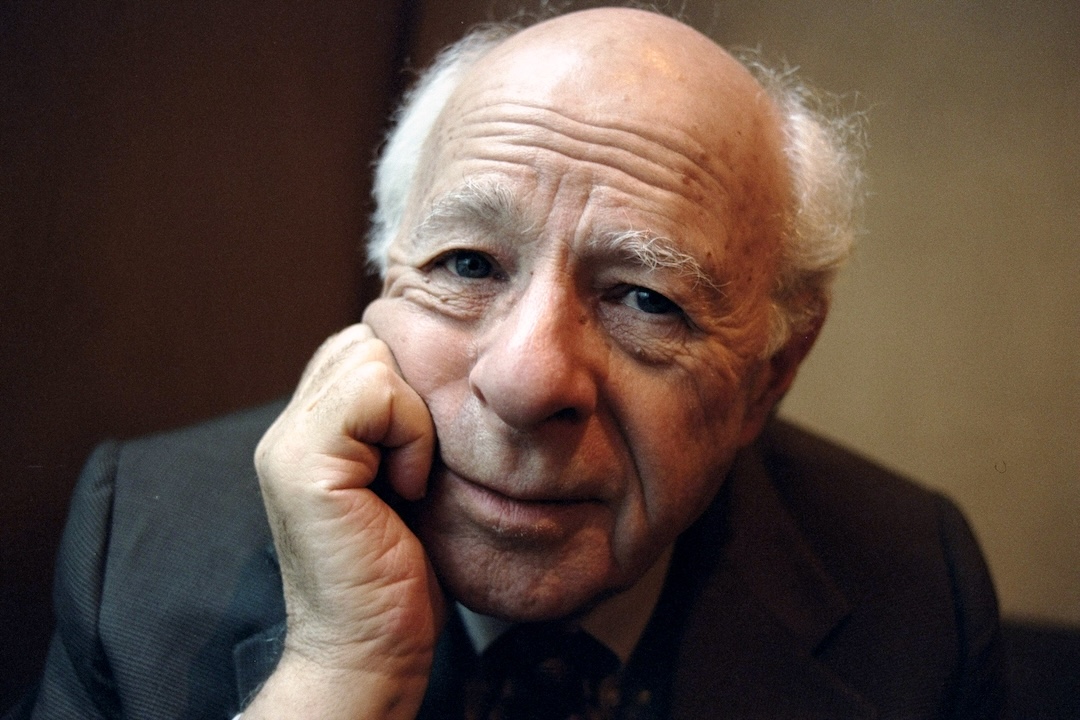

If feminists taught us that the personal is the political, Norman Podhoretz remained committed, probably to the very end, to the proposition that the political is personal, and only personal. (Jon Naso / NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

A personal word about Norman Podhoretz, the neoconservative longtime editor of Commentary, who died two days ago.

As some of you many know, back in 2000 or so, I interviewed a bunch of conservatives for a magazine piece I was doing. Amazingly, I got an interview with Bill Buckley, an interview with Irving Kristol, and an interview with Norman Podhoretz. I spoke with Buckley in his Upper East Side town house on Park Avenue, surrounded by portraits of his wife and little dishes of cigarettes. (It was more town than house; I don’t think I’ve ever been in a personal dwelling that big.) I spoke with Kristol in an ugly office in Washington, DC; I’m guessing, though I can no longer remember, that it belonged to the Public Interest, the journal he was editing at the time or had been editing until recently. And I spoke with Podhoretz at a coffee shop in the Hamptons somewhere, maybe Bridgehampton, where I think he lived.

Amid this trio, Podhoretz stood out in several ways.

First, he was the obviously the pettiest. He rehearsed his slights, he recited feuds, he remembered ex-friends more than friends. All of it was packaged in the bric-a-brac of world history — you know, the bloody crossroads where Arthur Koestler and People magazine meet — but you’d have to be a psychological naïf not to see the latent grammar in the surface script. If feminists taught us that the personal is the political, Norman Podhoretz remained committed, probably to the very end, to the proposition that the political is personal, and only personal.

Second, of the three men, he was easily the least interesting. Buckley had his undeniable charms. Though Kristol’s intellectual faculties were not what they once had been, he struggled, somewhat heroically, to understand things, and what he had done in the world, to the very end. He was a true ideologue, in the best sense of the word, trying to make the world make sense through the prism of ideas. Podhoretz was more Rumpelstiltskin, without the humor. Just an id of memory and grievance, sure, in that way some people are, that his stories were worth telling, unaware how much of a bore he really was. I have a visceral memory of trying to stay awake in the very hot coffee shop.

Last, and now I’m probably merging here his writing with his conversation, he was what the kids would call thirsty. With one exception (I’m thinking of a much younger, even thirstier journalist), I’ve never met someone who so desperately wanted to be an intellectual just for the sake of being seen as one. It’s not just the books ostentatiously referenced. It’s the groove of the references. It’s not just the name-dropping. It’s the way that the social apparatus of an intellectual scene drives, in a structural sense, the name-dropping. In any conversation with an intellectual, you can feel the hunger for or delight in ideas, whether they be political or aesthetic or historical or religious. It’s not the person’s intelligence or their agility you sense; it’s their desire. Which finds expression in conversation itself, in the give and take. With Podhoretz, you felt desire, but it wasn’t for ideas; it was for being thought of as an adept at ideas. You felt it ten minutes into the conversation. When you realized you weren’t in a conversation at all.