Khalid Bakdash and the Tragedy of Syrian Communism

Khalid Bakdash became the first communist MP in any Arab country when he was elected to the Syrian parliament in the 1950s. Bakdash’s party was once a major political force, but it faded into irrelevance after forming a coalition with the ruling Baʿathists.

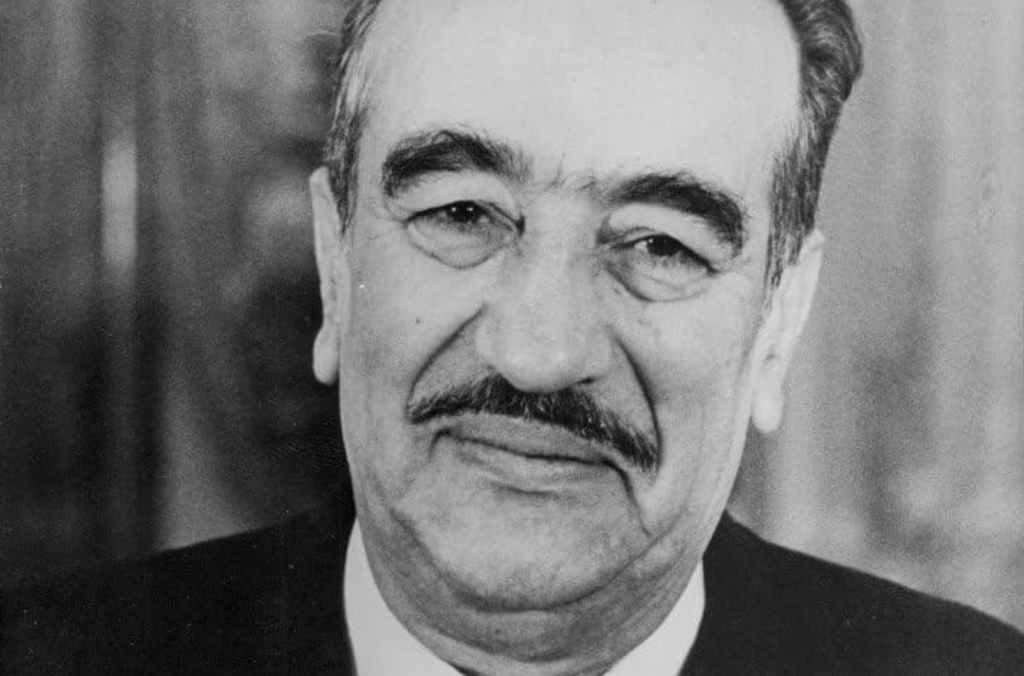

Khalid Bakdash became the most significant communist leader not merely in Syria but throughout the Arab world. (Syrian Modern History / Wikimedia)

The fall of the Assad regime last December, after fifty-five years of hereditary dictatorial rule, was as momentous and unexpected as its beginning and endurance since the 1970s. Amid the unprecedented and uncertain transformations that Syria is undergoing today, what significance do left-wing ideas still have for postcolonial Syria?

Rosa Luxemburg recognized in her 1913 work The Accumulation of Capital the constitutive influence of colonialism on the destructive formation of ninetenth-century capitalism. The Italian Marxist historian Domenico Losurdo has criticized Western Marxism for its blindness to the colonial question and its theoretical Eurocentrism (as well as its dismissal of Joseph Stalin’s legacy). Yet his books are limited to a critique of the Western canon itself.

In the period between Luxemburg and Losurdo, African and Asian communists have been largely absent from the theoretical narratives of international communism, and even more so from analyses of the specific conditions against which they struggled. Focusing on the checkered legacy of Syria’s Khalid Bakdash (1912–95) in all its global, regional, and local dimensions is a way of revisiting the wider history of the Arab communist movement.

Bakdash was the towering figure of Soviet-aligned communism in a region struggling with colonialism and its legacies, including low levels of industrialization, sectarianism, patriarchy, and neo-feudalism. Bakdash’s political life encapsulates the constraints and contradictions of communism during the Arab Cold War, the transition from Stalinism to independent Marxism-Leninism at the regional level, and the communist splits and persecutions at the national level during the period of Assadist rule over Syria.

Bakdash became the most significant communist leader not merely in Syria but throughout the Arab world, creating a Stalinist personality cult around himself. In the words of the late historian Tareq Ismael, “He ruled the party in the name of Khalid Bakdash, not in the name of communism.” The party that Bakdash forged supported the Assad regime until the very end, as did some left-wing groups worldwide in the name of anti-imperialism. How can we account for today’s situation while avoiding the temptation to read the present backward, whether in apologetic or defiant, accusatory or dismissive terms?

The Eastern International

Born in Rukn al-Din, a predominantly Kurdish quarter in Damascus, Bakdash earned a scholarship to attend Damascus’s elite Anbar School from 1925 to 1929. He proved to be an outstanding student who already displayed the charisma and oratorical skill that would soon propel him into the world of communism. He joined the Communist Party of Syria and Lebanon (CPSL) as an eighteen-year-old law student.

Bakdash soon led a coup against the party’s founders for being too Francophile and too workerist as well as insufficiently nationalist. He was the political child of the Third International and Moscow’s cadre academies. After leading the purge of the party’s old guard in 1932, Bakdash volunteered to go to the Soviet Union to study Russian and the national question.

The sources on his life in the Soviet Union are scant. He may well have encountered Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev’s subversive ideas of Muslim national communism and visited Baku University to meet Bandali al-Jawzi, a well-known Palestinian professor and author of the first Marxist book on The History of Intellectual Movements in Islam, published in 1928.

Thanks to Masha Kirasirova’s remarkable archival research, we do know that Bakdash enrolled at the Comintern’s Communist University of the Toilers of the East and later studied at the Institute of Marxism-Leninism. In Moscow, Bakdash was trained in historical materialist methods, Popular Front organizing, and the ideas of state socialism. He also learned to master party bureaucracy and report-writing. Soon he established himself as the gatekeeper of the Comintern’s Arab section.

Among Bakdash’s contemporaries in Moscow were other future leftist statesmen, Third World leaders, and communist writers. They included Vietnam’s Hồ Chí Minh, China’s Deng Xiaoping, and Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta as well as M. N. Roy, the founder of the Mexican and Indian communist parties, and the Trinidadian Pan-Africanist George Padmore. The Turkish poet laureate Nâzım Hikmet, the African American Harry Haywood, the Iraqi Yusuf Salman Yusuf (Fahd), and the Palestinians Bulus Farah and Muhammad Najati Sidqi were also present.

During Bakdash’s leave from Damascus, the CPSL was run on his behalf by Farajallah al-Hilu and their mentor Artin Madoyan, whose memoirs provide many of the details of our account. A professional among amateurs, he was ready to turn Marxist-Leninist theory into Stalinist praxis upon his return to Syria.

In 1943, Stalin dissolved the Comintern. This was also the year of Lebanese independence, and the party split into a Lebanese and a Syrian (SCP) branch. In his writings, Bakdash gives the rationale for this split on the grounds that the two countries were at different stages of development.

Bakdash’s SCP justified collaboration with nationalist parties and notables during and after World War II on a similar basis, arguing that Syria was not ready yet for the stage of the rule of the proletariat. He ran on a reformist platform in Damascus that did not mention socialism, and his way of campaigning for national independence was barely distinguishable from that of his rivals. Bakdash appreciated Arab and Islamic heritage and quoted Quranic injunctions to mobilize his audience in this period. His party put revolutionary class struggle on hold and emphasized instead the party’s national character.

The Palestine Question

Neither the Lebanese nor the Syrian branch of the party won a seat in these wartime elections. Nevertheless, after the defeat of fascist Germany, the popularity of the communists grew across the Arab world. By some counts, party membership in Syria reached 18,000. Then came the Soviet Union’s shock decision to vote for the partition of Palestine at the UN in November 1947.

Bakdash forced his party to follow the Soviet line and was criticized heavily for his obedience. On the eve of the UN vote, the party’s headquarters in Damascus was set ablaze. Al-Hilu and many other comrades argued that their chairman’s decision was not only morally objectionable but also a betrayal of the party line since 1924 and entirely out of touch with the Arab masses. They implored him not to sacrifice the foundational Arab communist principle of national liberation at the altar of internationalist pressure.

Bakdash defended his decision, viewing the Palestine question merely in Soviet anti-imperialist terms. He overlooked the colonial question at stake, presenting his dissenting comrades with a utopian vista of Arab and Jewish workers, peasants, and communists who would join forces to overthrow the ruling reactionary classes.

In the hour of the greatest practical need, Bakdash misjudged the nature of the Zionist settler-colonial project as a distraction from the greater British-American threat to the region. Bakdash’s loyalty to Stalin meant that Arab communists would be stigmatized as instruments of foreign powers for years to come.

The Arab Cold War

The Nakba made three-quarters of the Palestinian population homeless in 1948. Arab governments were blamed for their inability to defend the land of Palestine. Syria experienced three coups the following year alone, the Egyptian monarchy fell in 1952, and the Hashemites were ousted from their Iraqi throne in 1958.

At the regional level, Syria became the big prize of the 1950s, in what Malcolm Kerr called the Arab Cold War. Ideas on Arab identity, nation-building, and state-building in Syria were as diverse as the global, regional, and local actors involved. Bakdash played an important role in keeping Syria immune to Western overtures and maintaining close ties to the Soviet Union beyond the period of Stalin’s rule.

In January 1951, he delivered a twenty-page position paper on democratic socialism to Communist leaders in Syria and Lebanon that gained much attention inside and outside the party for its surprising ideological rigidity. In the context of the anti-communist dictatorship of Adib Shishakly in Syria, Bakdash enjoined his comrades to reconnect to basic communist principles and remember the party’s long-term socialist goals.

Bakdash argued that because Syria was in an “extremely backward” region and so “far removed from Marxism,” national liberation should be sought in stages: first, by putting an end to “imperialist political and economic domination and its agents,” and by “liquidating the remnants of feudalism in our country.” Then the party should work to “strengthen the popular democratic regime” and mobilize the peasants and workers in (and between) elections in order to create the “conditions necessary for the realization of socialism in the country.”

The party needed to move beyond “making noise” and focus on building a comprehensive infrastructure in order to persuade the Arab masses, especially in rural areas, that communist alternatives suited them better than the existing regimes or parties claiming to be “socialist, such as the Arab Socialist Party, the Islamic Socialist Front, the Baʿth Party in Syria and the Progressive Socialist Party of Jumblat in Lebanon.”

Internationally, the party should maintain a strategic alliance with the Soviet-sponsored international peace movement, while being critical of its naive optimism. Regionally, the party “must work constantly . . . against the aggressive schemes of the Anglo-American imperialists aiming to occupy our land, and against the treason of our rulers.”

The United Arab Republic

Observers of Syria generally regard the period between the fall of Shishakly in 1953 and the union with Egypt in 1958 as the country’s democratic years. In the 1954 elections, the only free ballot to take place in Syria, Bakdash won a seat as the first communist ever elected to an Arab parliament. He became a key player in Syrian and regional politics.

The popularity of the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, especially after his victory at Suez in 1956, posed a threat to communists in the region, and Bakdash was among the first to smell the danger. When Baʿathists first mooted the idea to unify Syria with Egypt in late 1957, the prospect split the communists, both at the base of approximately 10,000 members, and in the party leadership.

Al-Hilu and many others supported the union on the grounds that Nasser’s Arab nationalism served as a vehicle for social emancipation. Bakdash rejected the scheme, knowing Nasser was neither a friend of parties in general nor of communism in particular. Instead, Bakdash proposed a federalist “minority report” for Syro-Egyptian relations.

Less than a year into the formation of the United Arab Republic (UAR), Bakdash’s fears were confirmed. All Syrian parties dissolved, and Egyptian officials treated Syria as a vassal state. UAR authorities also arrested, tortured, and killed his comrade al-Hilu. The three ill-fated years of unification produced the ideological irony that the Stalinist Bakdash, who survived the UAR in exile in Beirut, turned out to be the defender of Syrian democratic principles against Egypt’s takeover of Syria.

From the mid-1960s, Marxist-Leninist splinter groups, samizdats, and reading circles proliferated across the world, often independently of or against the Soviet Union and China. The resounding Israeli military in the June 1967 war against Egypt and Syria marked a turning point for the Arab world in general, and for nationalists and Marxists in particular. The Palestinian cause radicalized a new generation of refugees and students to take up arms.

At the same time, the defeat provoked the established generation of leftists to reconsider the premises of political praxis. In Syria, the eminent philosopher Sadiq al-’Azm pathologized the Arab “militant’s mind.” The influential theoretician Yasin Hafiz identified “anachronistic ideology” as the cardinal analytical sin of Syrian communists.

National Power Politics

A military coup in March 1963 was the beginning of six decades of Baʿathist rule over Syria. At the time, it seemed to be just one more military intervention in domestic politics. After internecine strife in the Baʿath Party, Hafez al-Assad took power in 1970 and went on to rule the country until his death three decades later.

Bakdash dissolved the Communist Party that he led into the Baʿathist-led National Progressive Front. Established in 1973, this front aimed at co-opting the Syrian left. Bakdash became a defender of Assad’s policies — and of violent repression, including that directed against Communists and the Left more broadly.

This aggravated a process of disintegration in the SCP. A group of communists around Riad al-Turk broke away to form the Syrian Communist Party–Political Bureau. They accused Bakdash of monopolizing decisions and subordinating the party to Soviet interests. Any disagreement with Bakdash meant expulsion, leading to repeated splits within the Syrian Communist Party.

Al-Turk died just a year before the fall of the Assad regime, after a lifelong struggle for a free and democratic Syria that included two decades in prison under the rule of Hafez al-Assad. His organization changed its name to the Syrian Democratic People’s Party in 2005. The Syrian Communist Party, by contrast, remained allied with the Assad regime until its fall in December 2024.

In the early 1970s, theory-oriented communist reading circles emerged in Syria. The Syrian Communist Labor League (Rabita al-’Amal al-Shuyu’i) bound these circles together in opposition to, and independent of, established communist parties.

The Communist Labor League criticized Bakdash for his reading of revolution as ongoing social progress in alignment with the national bourgeoisie and under Soviet guidance. It similarly dismissed the SCP–Political Bureau’s understanding of revolution as merely democratic and therefore reformist. In contrast, Rabita al-’Amal al-Shuyu’i’s evolving concept of revolution derived from a reading of class struggle that seems to have been inspired by the work of Louis Althusser.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Syria witnessed widespread oppositional unrest, triggered by the Syrian army’s intervention in Lebanon in 1976. The Communist Labor League criticized the Assad regime as well as the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood that opposed it.

The league considered the regime to be a corrupt fascist dictatorship that acted against the interests of both the popular classes and the Palestinian cause, while the brotherhood was antidemocratic and sectarian, and its use of violence objectionable. From this perspective, both were different expressions of the same petty bourgeoisie. The league argued against understanding Syrian society through the framework of sectarianized identities and against relying on Islam as a viable source of opposition or emancipation.

After Hama

In 1982, the Syrian regime killed tens of thousands of civilians in what is remembered today as the Hama Massacre. Thousands more were assassinated, imprisoned, or forced to leave Syria. In the words of the former SCP–Political Bureau member and intellectual Yassin al-Haj Saleh, what happened in Hama in 1982 was “the endpoint, not to the conflict with Islamists, but to any political rights for all Syrians.”

For Bakdash, the revolution was the state, and the state was the revolution. Over time, his political radius shrunk from internationalist beginnings to localist endings. The very state that Bakdash had envisaged at the beginning of his political career and participated in by taking his SCP into the National Progressive Front was the state that went on to decimate the ranks of communist revolutionaries in Syria.

Bakdash remained loyal to Assad, defended Stalinism, and opposed Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika as a Western conspiracy aimed at destroying socialism. At the end of his life, he installed his wife Wissal Farha Bakdash and later his son Ammar as his successors. Ammar Bakdash, who had followed in his father’s footsteps to study economics at Moscow State University, left Syria after the fall of Assad and died shortly afterward in Greece.

Nevertheless, throughout decades of authoritarian rule, revolutionary ideas have persisted in Syria until today, a year after Assad’s ouster. The experience of Syrian communism cannot be reduced to the legacy of Bakdash. It has remained a living and contested current in Syria’s intellectual and political life. Revolutionary ideas have persisted and continue to shape discussions in cultural production and intellectual circles, in labor organization, in underground newspapers, and prisoner networks, both inside the country and across the diaspora.