Democrats Lost Working-Class Voters’ Trust

Thanks to decades of failing to seriously address the economic struggles of ordinary Americans, the Democratic Party brand has cratered in the Rust Belt and is increasingly flagging with working-class voters of all races.

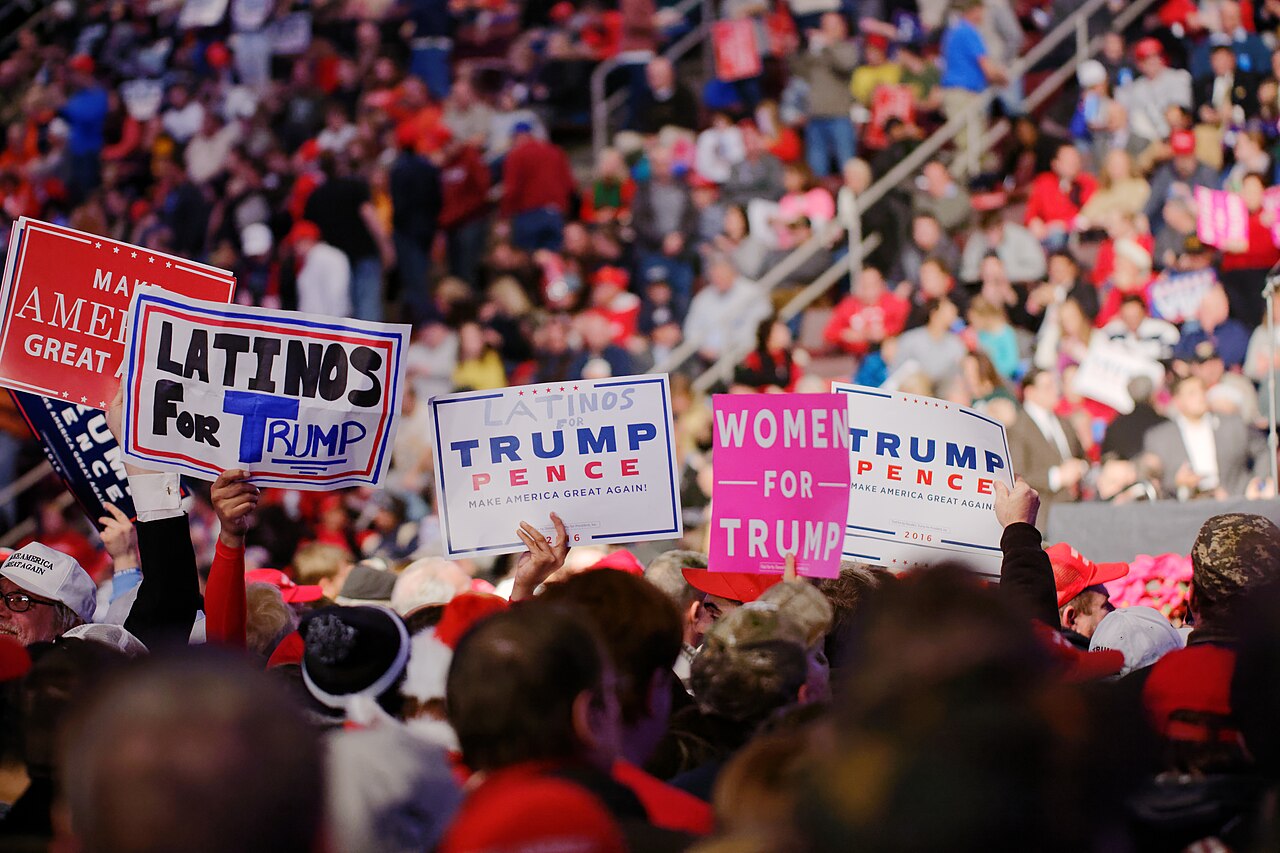

Donald Trump supporters hold signs in support of him at a rally in Hershey, Pennsylvania in 2016. (Michael Vadon / Wikimedia Creative Commons)

- Interview by

- Rachel Rybaczuk

As the 2026 midterm elections approach, the question of why Democrats have increasingly struggled with working-class voters — and why Donald Trump’s Republican Party has been able to make inroads with them — is becoming more urgent. This question has long occupied the Center for Working-Class Politics, who published the results of an exhaustive survey this fall on the attitudes of working-class voters in the Rust Belt.

The survey found that voters are hungry for candidates running on ambitious, economic populist platforms. It also found that voters tend to penalize candidates merely for identifying as Democrats, showing the extent to which the party brand has been tarnished in the region.

Center for Working-Class Politics director Jared Abbott recently talked about the report’s findings with sociologist Rachel Rybaczuk on her podcast Shifting Terrain. The two discussed how and why the Democratic Party has lost many working-class voters.

That loss of working-class support has not been confined to the Rust Belt, however, or to white voters, as was once imagined; more and more Latino voters have also been moving to the Right. To understand this trend, Rybaczuk also interviewed René Rojas, an assistant professor of human development at Binghamton University and a Catalyst editorial board member, who has recently analyzed Latinos’ role in the 2024 election. This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

The first thing we learned is that Democrats have a toxic brand in the Rust Belt, and we wanted to see just how important that might be in elections. So we tried to get the strongest candidates that we could find in terms of reaching working-class voters in the Rust Belt.

We put together these profiles of candidates that were economic populists: they’re talking about the harms that are [caused by] elites and the need to raise up working-class folks and give them a shot at a better future and so on. We made different candidates Democrats, and we made some independents.

They were exactly the same except for the partisanship of the candidate, and that one fact alone dramatically penalized candidates in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio. There’s something about just being a Democrat, which is not necessarily putting Democrats completely out of contention, but which is dramatically penalizing them.

We wanted to know why and what we could do about it. And we found that when you ask people, “What do you think about when you think of the Democratic Party?”, a lot of people do talk about the party being out of touch culturally and being too woke and too extreme and that sort of thing.

But more than that, people focused on the [idea that] Democrats are just not trustworthy. They’re not a party that people believe would actually deliver on the things that they say they’re gonna deliver on, and they’re not a party that working-class people think actually represents their interests.

Part of our goal then was to figure out what are the types of policies that Democrats and independents for that matter could run on, which might be most compelling to working-class voters. So the last part of our survey was to do a test of twenty-five different economic proposals, and we forced people to choose which of these is most important to you, which do you think should be prioritized the most.

We found that regardless of partisanship, regardless of class, regardless of geography, and so on, there was a set of robust progressive economic proposals — everything from capping prescription drug prices to trying to ban members of Congress from engaging in stock trading, and even more expansive programs stopping corporations from involuntary layoffs of workers without just compensation — that polled very well, basically across the board.

The punchline there is that while Democrats have this major reputational problem, one of the ways in which they’re gonna be able to regain some of that trust is offering a set of clear, economic, bread-and-butter proposals, which show working-class people that Democrats really care about them, and that they’re focused like a laser on making a better future for working-class voters.

Have you thought about the results of this research and reconciling those things over time — looking historically, in addition to how we got to where we are right now?

Historically, starting back in the 1930s under the administration of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, the Democratic Party has been the party associated with and in fact delivering all kinds of benefits, from Social Security to basic labor protections and union rights.

That started to change with the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, which had the effect of gutting many communities, particularly in southern towns that had textile manufacturing and other sorts of manufacturing that could be sent to Mexico.

Even before that, in the 1980s, as European and Japanese competition for manufacturing got stronger and stronger and communities throughout the Rust Belt were losing jobs, the Democrats didn’t do very much to try to stop it. They didn’t help unions very much.

All this came together to create a toxic brew in which, many working-class people just didn’t trust the Democrats anymore, as they moved away from a focus on working-class issues and toward a greater focus on highly educated voters, starting with the Clinton administration.

What about the Republicans? They haven’t delivered for working-class people. And they keep promising; at least Donald Trump does. But whatever he says, “we brought jobs back to this John Deere factory” and so on — you look into the details, and you find that that’s not true at all.

His message starting in 2016 was so powerful and so different from what people had been seeing before from Democrats or Republicans. His affect really connected with people on a visceral level: saying, “You guys have been getting screwed for decades, and I’m gonna offer something different. I’m gonna come in and undermine all of the powers that have been keeping you guys down for so long and drain the swamp.” He literally used language that he took from speeches by Richard Trumka, the president of the AFL-CIO.

That messaging really struck a chord with people and [still is], even though he’s not really delivering for people very much. A lot of voters have just decided that he’s their only salvation, and he’s a businessman — he’s a disruptor, and they can trust him. And they’re willing to give him a lot of latitude.

But I think that is really powerful: even just symbolically: “I hear you. I feel you. I’m mad. I’m angry like you are.” That’s not something that Democrats had really been offering, and that really stuck a chord.

I’m not saying the other things didn’t matter, in terms of his use of racism and xenophobia. Those were really important to the story as well. But I do think that they’re all bundled up in this package of anti-elitism and, “We’re fed up, and we’re not gonna take it anymore, — and this guy’s an asshole, but he’s our asshole.”

So along those lines, thinking about the Republicans, what have they said concretely that you think is appealing to working-class voters?

Part of it is negative portrayals of the Democratic Party. That’s very powerful. Republicans are extremely effective in finding those inflection points, those issues that they can magnify into central issues in American politics. Like, say, trans women in women’s bathrooms or something like that, which they clearly poll-tested maybe a decade ago and discovered that this would be an important thing for them to latch onto to try to vilify the Democrats as being extreme and out of touch.

And they have a much better media echo chamber than the Left does. They have decades of experience with alternative media that the Left has in a much more limited way.

They’ve been focusing on addressing immigration, which was a big problem that the Democrats just simply didn’t address in the Biden administration until it was too late, essentially. The other thing is that they’re able to put forth this idea that they care about working people, and that they have a focus on bread-and-butter issues and on trying to make the economy hum again and do anything that they can to create economic opportunity for the American public: “We’re gonna do anything we can to bring back jobs, even if it means tariffs; we’re gonna do anything we can to create economic opportunity.” It might be bullshit in reality, and I think it is, basically. But it’s been pretty effective in reaching working-class voters.

I understand, and I believe that people are responding favorably to the survey asking about these economic populist platforms or positions. But the things that are so powerful are about immigration, and this sort of cultural value of who’s in and who’s out, and trans athletes or trans women in bathrooms. So which is it?

It’s both. There were a lot of people that initially were just pissed off that the Democrats were not delivering for them economically, and it’s all caught up in the fact that the Democratic Party image and the focus of the party culturally became much more focused on college-educated folks. And the liberals basically had a completely dominating worldview in much of the mainstream media for a really long time.

Those things come together to create a sense of alienation from and feeling condescended to by Democrats. And I think that a lot of these policies around trans issues and immigration are, to many folks, another example of, “Democrats don’t care about me. They care about these other people.”

Does that mean that there are no people who are completely motivated by anti-trans attitudes or anti-immigrant attitudes? Obviously not. I don’t think we can say it’s one or the other of these two things. Because in many ways the economic piece of this gets sort of transmuted into the cultural aspect of it, even on something like immigration.

René, you coauthored an article with Maribel Tineo titled “The Latino Rebuke.” I thought the article was a persuasive explanation of this push and pull of the cultural and economic forces at play, with a particular focus on working-class Latinos, a group that generated many headlines following the 2024 election. Does this research that you’ve done on the Latino voter have broader implications for working-class voting patterns across race?

I think it does. It should help illuminate how we understand not only how Hispanics or Latinos are voting, but how all types of working people are voting.

[A typical way to explain] working-class support for MAGA has been to attribute this shift to white workers’ racism, that they can’t help but support Trump when he comes on the scene, even if it goes against their interests. So they started to make similar claims about Latinos: they too are sexist; they too can be xenophobes; they too can be caught up in white-supremacist ideologies.

We just found that was unconvincing, going back many generations. Latinos have always reported more socially conservative opinions around, for instance, same-sex marriage back in the nineties, and on reproductive rights and abortion. Those positions — those cultural orientations, if you want to call them that — didn’t translate into far-right-wing political attitudes in voting behaviors. So what needs to be explained is the shift, and if their cultural attitudes aren’t really changing, there must be something else at work that’s moving them in this other direction. I think a large part of that is quite reasonable frustration with what’s on offer in American politics.

What did the Democrats offer the Latino voter over the years that brought them to vote Democrat that changed? And what did the Republicans say that was so compelling this time to swing the vote as much as it did?

If they’re increasingly rejecting the Democratic Party, that didn’t mean that they’re going to automatically flock to Trump and MAGA. There’s got to be something positively attracting them to right-wing populism. I think, interestingly, a lot of it was articulated around immigration.

We want to be very careful about how we make this argument, but essentially — during these elections in particular, but increasingly now for some time — when it comes to reaching out to Latinos, Democrats have been leading with the issue of immigration. MAGA is a threat to immigration. They’re treating your people, your cousins, what have you, badly. They’re rounding them up, locking them up, and we expect you all to come together as a monolithic bloc. Because you share some kind of mythical pan-ethnic connection and a desire to defend immigrants against xenophobia.

It turns out that that’s not what was first in mind. That wasn’t the priority of Latino voters, and they were looking for something more substantive to help them meet their needs in increasingly challenging times.

What did the Republicans offer that was so compelling?

In the absence of a set of welfare policies that can protect Latinos — if they’re unable to hold onto their jobs, or if their wages are cut — then Latinos, like all other workers, are going to lean toward more individual, more competitive strategies.

Policies, for instance, that promise to limit the entrance of new competitors, possible immigrant workers, competing for those precarious jobs will look more appealing in the absence of better alternatives. Promises to revive certain sectors of the American economy — remember that even with the decline in manufacturing, Latinos remain disproportionately represented in those blue-collar jobs.

What’s happening in my view is that they’re ditching the Democrats and they’re trying out something else. It does not mean at all that they will be permanently committed to white supremacy, to xenophobia. Again, when other things aren’t working out, they’re testing the waters. They’re testing membership in the MAGA coalition to see if it might help.

We can all understand that the economy has changed over decades, though what’s striking to me is that, you know, [a right-wing refrain has] been, “Immigrants are taking your jobs.” Now recent immigrants are also afraid of immigrants taking their jobs.

You increasingly see immigrant Latinos adopting anti-immigrant views, and that seems like a contradiction, but it really needn’t be.

It makes a lot of sense. Naturalized citizens, immigrant citizens, voted at higher rates for Trump than native-born Latinos. One way to think of this is to say, “She’s an immigrant. Why would she adopt anti-immigrant views?”

But that person isn’t necessarily making her calculus in those terms. It might be totally rooted in, an assessment of her own situation, her own interests: I need to hold onto this job, and I need to make sure my wages at least don’t decline any further for my sake, for my kids’ sake. Now, let me think about how to go about doing that. What the Democrats are offering don’t seem to offer much in terms of helping me do that.

But wait a second. Here’s MAGA. And I’m not against immigrants, but if we can restrict the inflow of possible competitors, that might help me, that might help my own interests.

René points out the failure of a culture-focused explanation for working-class Latinos’ swing to the right. He makes a strong argument for messaging and action around jobs and the practical needs of working people, something the Democrats have failed to do.

Jared, something I learned in season one of my podcast talking with Sarah Jaynes, the director of the Rural Democracy Initiative, is that voters who are conservative are open to various policies one might consider more progressive, but once they’re labeled Democrat, they’re not interested anymore.

This also comes up in your research, and the insight isn’t new. Why is it taking so long to be understood and acted on by politicians?

It’s not that easy to fix. If you’re a Democratic politician, you’re limited in your options for how you address it without just leaving the party.

Dan Osborn, the Nebraska candidate for Senate in 2024, who’s running again, was able to run on certain things that have not been coded as Democratic, and he’s an independent candidate. So he got a really favorable hearing among Nebraskans because he had these policies, like the right to repair — which is something that enables people to basically be able to fix everything from farm products to iPhones in a way that they’re not able to right now and would be a big help to people across the country. That was something that Democrats have kind of been talking about, but only a few. And it wasn’t coded as Democratic, like the Green New Deal or something like that. You combine that with the fact that he himself wasn’t a Democrat, and then he gets a fair hearing.

But how does a Democrat do that? That’s the question. Sometimes they need to find policies that are not coded as Democratic, but ones that are still solidly progressive. Medicare for All is generally popular, for instance, but it’s very Democratic-coded to many voters. There are things related to health care that we don’t call Medicare for All that are gonna be really popular among those voters. So that’s part of the story, how you frame the policies.

The other part of it is, you need to put some distance between yourself and the Democratic Party establishment. We talk about Jared Golden or Marie Gluesenkamp Perez; these are not the most progressive folks in Congress, but one thing that they do really effectively is talk about how both parties are out of touch. All they care about is the folks in their district and delivering for working-class people, and more Democrats need to do that.

Marie Gluesenkamp Perez in particular — watching her ads, they really align with this presentation of working-classness and appearing working-class, and how powerful that is.

Our research shows that actual working-class candidates do much better among working-class voters than middle-class candidates do. Whether or not you are legitimately working class is a separate issue. But generally, when we say that somebody’s a working-class candidate in a survey, they get a five-, six-, or seven-point bump relative to candidates who are otherwise very similar.

We also see this showing up in real election results. We just did an analysis of candidates from 2010 to 2024, where we found that those who present themselves as working class in their messaging do significantly better in communities that have high percentages of working-class voters than those who do not.

That’s not a magic bullet, but it’s a really important part of the story. Only 2 percent of members of Congress and about 3 percent of people who run for Congress have a working-class background. So that’s an area where we can make real improvements.

How did you present working-classness? To people taking the survey, did you just simply say, this is a working-class candidate, or were there characteristics of working-classness you presented to give them that persona?

We just did as simply as the occupation: “This is a schoolteacher,” or “This is a manual worker.” We gave a bunch of different occupations that were working class, and all of the results are pointing in a similar direction: that the representation as working class really matters. Recruiting more working-class candidates, as some places are doing, is going to be a really important part of the toolkit here.

I spoke with Les Leopold, who’s a collaborator in this research that you’re talking about. He and I talked in a previous episode about unions and building worker power. He was clear that workers need political power and proposed an independent political party, but he did talk about the survey results, how favorably people saw this independent — should we call it a third party? What is your take on this in practice?

There are plenty of places where there’s just no chance that a Democrat’s going to get elected. And those are places where having more independent candidates, like a Dan Osborn, can make a real difference and could actually help to get more working-class-focused candidates elected — and even beyond that, help the broader process of getting working-class politics back in local, small-town and rural communities. It’s part of a broader process that great organizations like the Rural-Urban Bridge Initiative and others are doing to try to create civic associations and rebuild the spaces for working-class people to organize and advocate for themselves that have been eviscerated by the basically disappearance of unions from small-town and rural America.

Is there anything more you want to say about working-class social and economic attitudes, political attitudes, or working-class voters broadly?

Two things. One is that, contrary to what a lot of these centrist reports you’re seeing say — that working-class folks are more conservative on economic issues than middle-class folks — that is not true. Our report shows that systematically. Working-class people are more progressive on a host of issues, and that tells us that the economic issues are the ones where, if we can raise the salience of these issues relative to more divisive social and cultural issues in the electoral scene, then that’s where Democrats are going to succeed and excel.

On the other hand, working-class people are not these crazy reactionaries that sometimes they’re portrayed as by the “basket of deplorables”–style language. Which is how Hillary Clinton described half of Trump voters in 2016. The reality is that working-class voters have become more progressive across all social and cultural domains over the last twenty or thirty years, compared to the previous period. So there’s a huge opening here for reasonably progressive policies that the vast majority of Americans would agree on that Democrats could run on.

We don’t have to throw in the towel and say, “Working-class people are conservative. We just need to move to the center.” No, there are lots of progressive, practical policies around social and cultural issues that working-class people overwhelmingly agree with. For instance, a path to citizenship for folks that have been here and played by the rules — like 75 percent of people agree with that in some surveys.

How do you account for the research findings you just cited? How are they capturing that particular conclusion?

We found that 10 to 20 percent of 2020 Trump voters agree with a more-or-less Bernie-style, economic populist platform on economic issues. Even with the 2020 electorate, which I think was more ideologically conservative than the 2024 Trump electorate. Even then, we’re seeing a percentage of folks in the Trump coalition that is way larger than the margins that we need to win in all the key swing states, who fit that profile of people that could be reachable by Democrats — if they have messaging around social and cultural issues that is culturally competent to working-class voters while still being progressive and defending communities and their right to a safe and and secure life for them and their families, and that also taps into strong economic populism.

You’ve been thinking about working-class voters for a while, and the Center for Working-Class Politics recently released a report based on a survey of 3,000 voters across Pennsylvania, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin. What did you learn from this research?