The Housing Crisis Is Solvable

British Columbia’s housing crisis is severe, but its root causes are familiar: exclusionary zoning, under-building, and chronic neglect of nonmarket housing. Economist Alex Hemingway’s proposals show how governments could reverse course, in BC and elsewhere.

British Columbia’s housing crisis reflects the same policy failures seen in high-cost cities around the world. The housing crisis persists not because solutions are unknown, but because governments refuse to act at the scale required. (SeongJoon Cho / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The magnitude of the housing shortage is huge and the problems chronic, but the housing crisis is solvable.

Throughout British Columbia (BC) and Canada, the housing crisis is marked by high rents and prices, a scarcity of homes, displacement, homelessness, and the quiet exclusion of people from entire neighborhoods.

While a boon to some, high housing costs are a millstone weighing on many households, a drag on the economy, and a barrier to progress in a range of other policy areas including poverty, affordability, climate action, and childcare.

The crisis is multifaceted, but three key areas of action stand out as fundamental to address it:

- Nonmarket housing: a major expansion of public investment is needed.

- Overall housing supply: tackling a severe shortage of homes including market housing.

- City-level roadblocks: ending apartment bans and other municipal barriers to housing.

We have seen a flurry of housing policy from different levels of government in recent years that aims to address precisely these issues. Yet there’s less to this flurry of activity than meets the eye. Reforms target the right levers — nonmarket housing, more supply, and zoning reform — but fall short in scale and implementation.

With the right policies in place, real progress could be made relatively rapidly.

Nonmarket Housing: Far More Investment Is Needed

While market housing supply is important, the market alone cannot solve the housing crisis. It is essential to significantly increase public investment in nonmarket housing to meet the needs of the people worst affected by the housing crisis, including those with low and modest incomes and racialized and indigenous communities.

For decades, Canada has underinvested in public, nonprofit, and co-op housing.

The result is that today only about 3.5 percent of the country’s housing stock is social housing, which is half the OECD average. While there’s been some reinvestment in recent years — both federally and provincially — it’s nowhere near the scale that’s needed after decades of neglect.

The federal government did once invest substantially in social housing — building roughly sixteen thousand new units per year in the 1970s and ’80s — but funding cuts in the 1990s saw that investment wither. And the provinces — including BC — did not fill the gap.

The consequences have included rapidly growing waitlists for social housing and the proliferation of homelessness in one of the world’s richest countries. Failing to ensure people can meet their housing needs comes at enormous social and economic costs.

To meet the backlog of need — and to significantly increase the amount of nonmarket housing in the overall housing system — BC should build at least twenty-five thousand new nonmarket homes each year. This would be an ambitious undertaking, and all levels of government would need to contribute. But it can be done if the necessary funding and political will are in place.

The provincial government currently targets only 4,500 new nonmarket homes per year. This is a major improvement from the previous BC Liberal government but not nearly enough. In turn, the new federal Build Canada Homes program is expected to create only an average of about 5,200 new homes per year spread across the entire country, according to the Parliamentary Budget Officer. In fact, the same report projects that overall federal housing funding will decline by 56 percent by the 2028–29 fiscal year as programs expire and cuts in Budget 2025 take effect.

Throughout Canada, including in BC, public investment in nonmarket housing is nowhere near where it needs to be.

To ramp up nonmarket housing production, the BC government should significantly increase capital grants to projects under programs like the Community Housing Fund to ensure that good nonprofit housing projects aren’t left unfunded. In turn, the federal government should step up with much more robust funding for social housing Canada-wide.

The province should also take the initiative itself to develop housing projects at a much larger scale, using a self-supported debt model to reduce the impact on government budgets. While rental income can defray some costs, subsidies, grants, and land contributions are crucial to achieve deeper affordability, especially for supportive and rent-geared-to-income housing.

To pay for stronger investment in nonmarket housing, BC should tax a portion of the staggering levels of land wealth in this province, particularly at the high end of the housing market. Indeed, the value of land under detached houses alone in Greater Vancouver was $744 billion in 2024 and residential property values in BC increased by $1.7 trillion over the past two decades.

Why the Rent Is Too Damn High: Scarcity and the Housing Shortage

The shortage of housing supply is a fundamental element of the crisis, alongside the shortage of nonmarket homes. We need far more homes of all kinds, including private market housing.

For some, the housing shortage is obvious; skepticism remains. A few key indicators can help us see both the rate at which we’ve actually been building homes and the scale and significance of the housing shortage in BC and Canada.

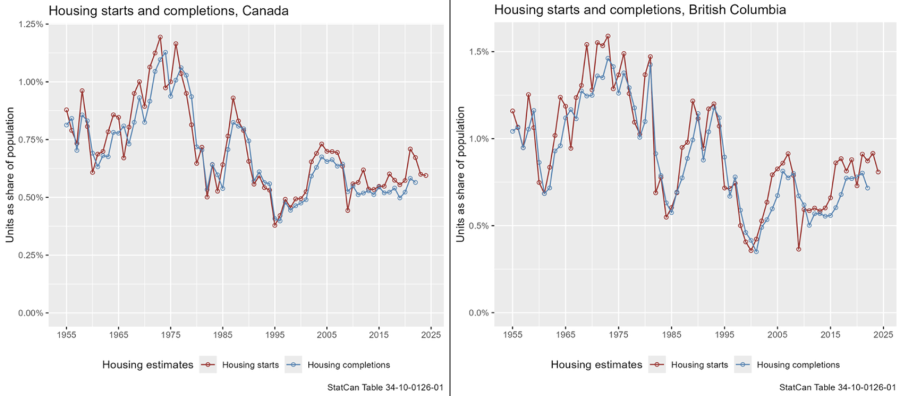

It’s often claimed that housing has been built at a rapid rate—and yet things haven’t improved. In reality, on a per-capita basis, housing starts and completions in BC and Canada have long been substantially lower than the levels of the postwar decades (see Figures). Even without adjusting for population, Canada only recently matched the peak in raw housing completions of the 1970s (in what was a country with a far smaller population at the time).

One clear indicator of the resulting housing shortage is persistently low rental vacancy rates in many Canadian cities over a long period of time. A balanced or healthy vacancy rate would be at least 3 percent, yet in the country’s most expensive cities rates have typically been well below that level for decades — often under 1 percent in Vancouver. Low vacancy rates present a huge problem for renters, especially for those with middle and low incomes as they give landlords enormous leverage.

When vacancy rates are low, reflecting a scarcity of homes, this tends to drive up market rents. When vacancy rates are higher, rent increases slow or rents fall. This is a consistent pattern over decades that is observed in a wide range of cities across Canada, as Jens von Bergmann’s analysis shows.

This year has seen a welcome uptick in vacancy rates and a decline in asking rents in some cities like Vancouver and Toronto, driven by increased supply and slower population growth. But lasting improvements in vacancy rates and rents will require a sustained, structural increase in new housing creation. The population effect — largely driven by recent lurching policy swings in immigration — is likely to be temporary, while the latest data show new housing starts trending downward.

Chronic housing scarcity and high rents also prevent many people from forming the independent households they would like to establish. Instead, people are forced to pool their income to afford housing. This takes many familiar forms: young adults living with parents longer, unwanted roommates, and unwanted multifamily household arrangements. Such living situations can be by choice, but data show they are more common in high-rent cities.

This phenomenon is referred to as “suppressed household formation” or “doubling up.” In Metro Vancouver alone, estimates suggest there are 130,000 to 200,000 suppressed households. This represents a huge pent-up demand for additional homes among people who live in the region, not accounting for those already driven out by high rents or who would like to move here.

As Jens von Bergmann and Nathan Lauster point out, even if the entire housing stock was socialized tomorrow, Canada would still face a severe shortage of homes, underscoring the need for both nonmarket and supply-side action.

Homelessness and housing scarcity are also closely linked. As one team of US-based housing researchers put it, “homelessness is a housing problem.” Careful analysis finds that rates of homelessness across cities track closely with housing shortages as measured by vacancy rates and rents. Their data show that even economically depressed cities like Detroit, where rental vacancy rates are high, have far lower homelessness rates than richer cities like New York or San Francisco, where housing is scarce and vacancy rates are low.

Ending homelessness will require a major expansion of nonmarket affordable and supportive housing, alongside strong tenant protections and income supports. But it also requires addressing overall housing shortages, which appear to play a key role in determining how many people are pushed into homelessness in a given region. When housing supply is scarce, it is the most vulnerable who are squeezed out of the system.

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation estimates that Canada needs to roughly double housing starts over the next decade to about 480,000 new units per year. Analysis by independent experts similarly suggests that Metro Vancouver needs to roughly double housing construction — amounting to about 600,000 new units over a decade.

Yet, as a recent Parliamentary Budget Office report notes, “the [federal] government has not yet laid out an overall plan to achieve this goal” of doubling homebuilding. The weak trajectory of housing starts tells the same story. Canada is nowhere near on track, and the policies needed to deliver this scale of construction remain largely absent at the municipal, provincial, or federal levels.

City-Level Roadblocks: Apartment Bans and Exclusionary Zoning

Cities control some key policy levers that determine whether governments and developers can build both nonmarket and market housing at scale.

Yet in cities like Vancouver, exclusionary zoning policies effectively ban apartment buildings on three quarters of residential land. The most expensive forms of low-density market housing (detached houses) can be built virtually anywhere, but not apartment buildings (the case of multiplexes is discussed below).

These apartment bans damage housing outcomes in several ways, as I have discussed in a previous analysis. First, they severely restrict the number of new homes that can be built in most neighborhoods and increase the cost of scarce apartment-zoned land. In a housing shortage, public policy should ensure that land where apartments are permitted is plentiful — not scarce and expensive.

Second, even where cities allow apartments, they typically require developers to navigate lengthy rezoning processes that delay housing being built and increase costs. For example, in Vancouver, nonprofit housing developers estimate that a rezoning process can easily cost $500,000 to $1 million. This undermines affordability in projects that do proceed and renders many others financially unviable.

Apartment bans also accelerate tenant displacement. By blocking apartments in wealthier detached-housing zones, cities funnel new development into areas with older apartment buildings. That pressure drives demolitions and pushes existing renters out of their homes.

Exclusionary zoning further confines apartments to arterial roads, exposing renters to noise, pollution and car traffic that harms health and well-being. When cities block apartments across large swaths of their core, they push development outward instead, increasing sprawl, lengthening commutes, raising per capita infrastructure costs, and worsening climate pollution.

Housing policy failures at the city level also lock people out of high-productivity urban centers, excluding them from job opportunities and higher wages. This, in turn, hurts economic productivity and widens inequality.

Cities cannot deliver an ambitious build-out of nonmarket housing or double overall homebuilding while apartment bans and other municipal-level roadblocks remain in place.

What’s Possible — And What’s Being Blocked

Two examples help show what’s possible when exclusionary zoning no longer stands in the way — and what cities block when they keep it in place.

First, the Squamish Nation’s Sen̓áḵw project — a large, indigenous-led housing development on reserve land in Vancouver — shows what happens when exclusionary zoning simply doesn’t apply. The Nation is building 6,000 rental homes near downtown Vancouver, including 1,200 below-market units. This scale of construction is possible because of the Nation’s leadership — and because reserve lands do not fall under the city’s exclusionary zoning rules.

Second, Auckland, New Zealand demonstrates what meaningful broader zoning reform can do. After the city significantly loosened exclusionary zoning, homebuilding surged. Between 2016 and 2021, Aukland approved 22,000 more homes than historical trends would have predicted, while inflation-adjusted rents stabilized even as they rose elsewhere in New Zealand. One study found that rents in Auckland would have been 28 percent higher without upzoning and another analysis suggests that rents at the lower end of the market eased even more than the median.

The Auckland findings are consistent with the broader research on the effects of adding new housing supply. One of the clearest mechanisms operates through “moving chains”: when new market housing opens, higher-income households move into it, freeing up older units and setting off a ripple effect that reaches more modest parts of the market. Researchers observed exactly this pattern in Helsinki, finding that “new market-rate construction loosens the housing market in middle- and low-income areas even in the short run.” Evidence from the United States and Canada points to the same basic dynamic.

The benefits are even more pronounced when governments build new social housing. These units offer immediate affordability, while the moving chain effect frees up older homes.

Solving the Housing Crisis

If the goal is to actually end exclusionary zoning, cities like Vancouver must allow at least six-story apartments by right, without discretionary rezoning, everywhere detached houses are currently legal. Indeed, allowing low-rise, single lot apartments broadly across cities would reduce project costs and create new homes faster. Auckland’s reforms also suggest that this would improve construction productivity and competition among home builders.

Cities must also eliminate barriers that function as de facto apartment bans, including frontage requirements that block single-lot apartments and onerous fees that undermine housing viability. Many of Canada’s most expensive cities increasingly rely on hefty fees levied on new apartments to fund public infrastructure. The result is fewer homes built and higher rents and home prices — shifting costs onto renters and first-time buyers while driving up per capita infrastructure costs that dense housing would otherwise reduce.

Yet even modest federal efforts to reduce these barriers have foundered. A recent commitment to cut development fees in half and replace lost municipal infrastructure funding has been significantly watered down.

The housing crisis is the product of public policy choices: decades of chronic underinvestment in nonmarket housing, sustained under-building, and exclusionary zoning that blocks apartments across most residential land in the country’s most expensive cities. Those policies can be changed.

Solving the housing crisis requires scaling nonmarket housing to match the backlog of need, building enough homes of all kinds to restore and sustain healthy vacancy rates, and ending apartment bans and other municipal “poison pills” so projects can proceed by right, faster and at lower cost. There is no shortage of housing policy announcements these days. But there is a shortage of follow-through and scale. The question is whether governments keep slow-rolling reforms that largely preserve the status quo of scarcity — or build a housing system designed to deliver abundant, affordable homes for all.

The housing crisis is solvable, but it will not be solved by half measures.