Jeffrey Epstein Wanted More War

New revelations show that Jeffrey Epstein’s interests extended far beyond money and sex with underage girls. Epstein used his influence to push aggressive solutions to geopolitical problems, particularly against America’s and Israel’s traditional adversaries.

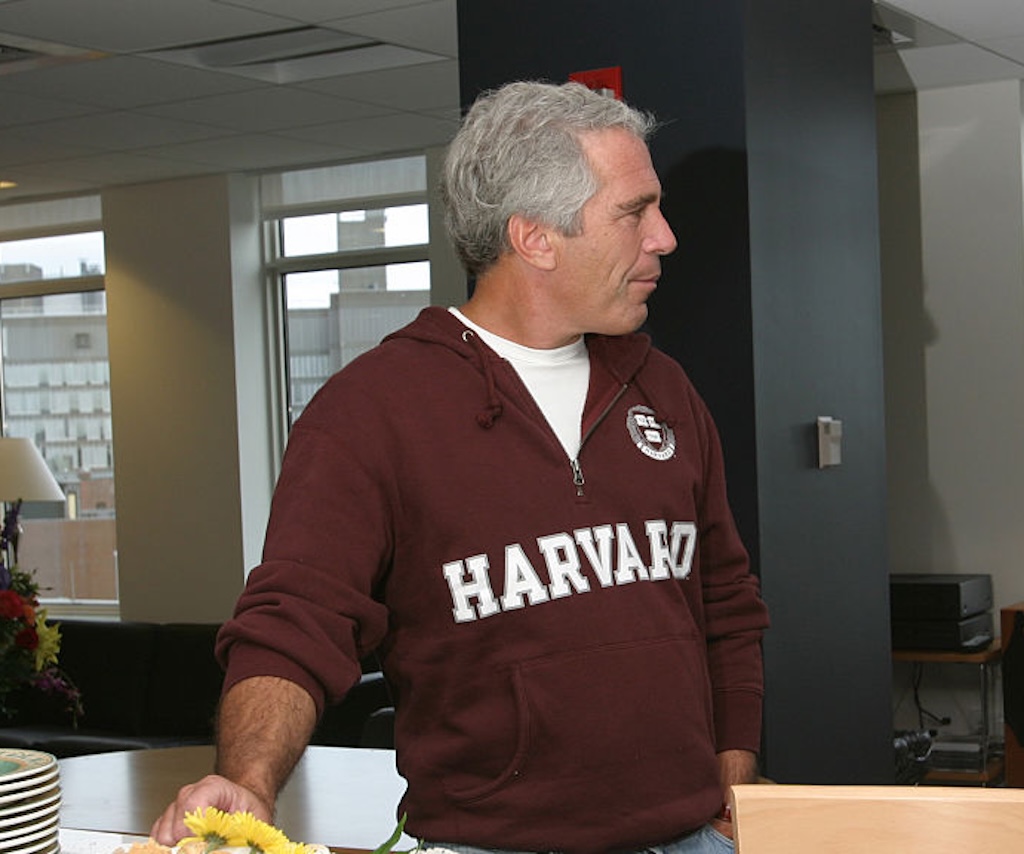

Newly released documents show billionaire sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein advising powerful figures like Steve Bannon and Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak on Iran, Syria, and China — usually advocating a hawkish foreign policy. (Rick Friedman / Corbis via Getty Images)

As more details come to light about Jeffrey Epstein, the billionaire sex trafficker is increasingly suspected of having used his wealth, influence, and connections to shape the way political power is used, particularly when it comes to foreign policy. If true, what kind of foreign policy did he favor and what goals did he hope to achieve?

We can catch a glimpse of the answers from the tens of thousands of Epstein-related files released last week by the House Oversight Committee, which show Epstein messaging with a variety of influential and powerful people on a slew of foreign policy topics. Over the years, Epstein exchanged emails with former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak opposing the Iran nuclear deal and favoring military action against Syria; expressed concern about Israel’s intensifying turn away from the two-state solution; and counseled Donald Trump adviser and China hawk Steve Bannon on how the Trump administration could best take on this leading global rival of the United States, to name a few notable topics.

The disclosures add to our understanding of Epstein’s still-murky role as a global power player, and what he actually used the influence he had amassed for. Simply put, if Epstein was using his connections to powerful people with some kind of aim in mind, it was decidedly not to make the world a better place.

“History Repeats Itself”

In the files, Epstein appeared to favor more aggressive solutions to geopolitical problems — particularly when it came to traditional adversaries of Israel, a country whose politics and national security the sex trafficker took a keen interest in, these and other disclosures show.

In 2013, for instance, as the escalating Syrian Civil War threatened its Iran-friendly strongman’s continued grip on power, Epstein encouraged former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak — a close associate and friend with whom he had been working to sell and develop Israeli weapons — to add to the mounting pressure on then-President Barack Obama to militarily involve the United States.

“Time to write the wait ‘until too late’ op Ed???” Epstein emailed Barak on August 31, 2013. That was the day that Barack Obama delivered a major speech responding to news that then-Syrian president Bashar al-Assad had deployed chemical weapons against his own people, something Obama a year earlier had said would trigger a US military response.

Epstein went on to advise Barak on what such an op-ed might look like. “I would use the opportunity to compare it with Iran,” he wrote. “The solutions become more compelx [sic] with time not less.” Bizarrely, he added that Barak “might point out the gassing of ‘women and children’ is an expressions from the 20th centry [sic],” and that “women are no longer equiv to children.” (Here and elsewhere, Jacobin has cleaned up Epstein’s often nonsensical punctuation for clarity. His spelling remains intact.)

As that email suggests, Epstein took a similar position on Iran. Despite sending a handful of more negotiation-friendly op-eds to associates over 2012 and 2013 — and despite soliciting Noam Chomsky’s supportive views on the Iran nuclear deal, which he then snarkily forwarded to Barak — Epstein, like the former prime minister, did not favor what became Obama’s signature foreign policy accomplishment of resolving the nuclear Iran issue through diplomacy. (Barak did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)

In February 2013, Epstein emailed another friend and associate, Larry Summers, seven articles about Middle Eastern geopolitics, the top one being a Wall Street Journal op-ed charging that Iranian leadership wasn’t serious about a deal and merely viewed negotiations as a pretense for buying time to develop a nuke. The subject line of Epstein’s email to Summers was “prep for dinner, israel pres briefing,” an apparent reference to then-Israeli president Shimon Peres (Epstein used “pres” as shorthand for “president” in at least one other email).

Peres was a longtime friend of Summers dating back to the Bill Clinton administration, and Barak has claimed that Peres was the one who had introduced him to Epstein. Still, it’s not clear what dinner or briefing the email was referring to. Peres did not visit the United States until the following year, though both he and Summers were at the World Economic Forum in Davos a month earlier, and Summers was a guest at Peres’s annual presidential conference a few months later in June.

(Jacobin reached out to Summers seeking clarification about this, including whether the meeting involved Peres and where and when it took place, but has not yet received a response.)

In any case, Summers, a former economic adviser to Obama, was at the time an influential voice even outside the administration. Later that year, he was highly favored by both the president and his team to be Federal Reserve chair, and only dropped from consideration when he voluntarily took himself out of the running.

As Jacobin reported earlier this week, Epstein had, at Barak’s request, edited one of his op-eds on the US-Israel relationship in 2014. He left telltale signs of his changes on the revised product: a trail of basic spelling and grammatical errors and inexplicable punctuation. Many of the passages in Epstein’s edit containing these errors concerned the threat of Iran.

“But I believe new opportunities are there for the taking. This opportunity, which might not occur again for generations ,is the potential to reshape our relationships with the Arab Moderates based on our common concerns . Extremism, Terror and Iran,” went one passage, its punctuation left intact here.

In another set of emails, it is former prime minister Barak — just two years out from serving as Israel’s defense minister — who is the one pushing a hawkish position on the Iran deal onto Epstein. In April 2015, Barak sent Epstein an email with the subject line, “Bill Clinton on Virtues of North Korean Nuclear Deal – History Repeats Itself.” The email linked to a video of Clinton espousing the benefits of a deal to curb the now nuclear-armed and bellicose North Korea’s own nuclear ambitions, echoing a common pro-war argument at the time that the Iran deal would lead to the same outcome.

Barak had sent Epstein an earlier email making the same point, titled “Bill Clinton 1994. Food for thought,” but had mistakenly attached a video of a CNBC interview he had recently done on the subject. The United States should give Iran an ultimatum to give up its nuclear enrichment program “or else,” Barak said in the interview, and could “destroy the Iranian nuclear military program over a fraction of one night.”

Years later, with Trump as president, Epstein expressed unease about possible US-Iranian rapprochement. “I told you this would happen. It’s going to get a lot worse before it gets better,” Epstein emailed in response to an extract from a May 2017 New York Times report about how the Iranian election victory of a pro-diplomacy reformist over his hardline anti–nuclear deal opponent would bolster Iranian outreach efforts to the West.

“Trump threatened Iran ;),” Epstein wrote to Bannon in July 2018, after Trump had made headlines with an all-caps tweet threatening Iran’s new president. “Yes, I saw that and immediately remember our conversation,” Bannon replied. The following evening, after Trump announced that “we’re ready to make a real deal” with Iran, Epstein called it “nuts.”

When Bannon informed Epstein a year later that Trump’s eldest son had been summoned to a meeting with the Senate Intelligence Committee over potential perjury charges, Epstein dismissed the story’s importance. “Focus on Iran,” he wrote.

“I’m all over Iran,” Bannon replied.

“They are very very bad guys,” Epstein wrote. “Patient smart spread Shia.”

The One-State Solution

Epstein’s hawkishness on Iran put him firmly in line with the Israeli political establishment, but there was one policy area where he dissented from the Israeli government at the time: the two-state solution.

Epstein appeared concerned that the increasingly right-wing Netanyahu government’s abandonment of the two-state solution was imperiling Israel. “It seems few people paying attention to Palestinians,” he emailed Noam Chomsky in December 2015. “Maybe next generation. Israel going further right it appears.”

While it’s possible to dismiss the email as Epstein simply telling Chomsky what he wanted to hear — at one point, he told Bannon that Chomsky had phoned him with jailed leftist Brazilian former president Lula da Silva (“What a world”) even as he was quietly backing Bannon’s work to put his far-right opponent Jair Bolsonaro into power — the concern pops up elsewhere, like in one of the error-riddled passages in Epstein’s edit of Barak’s op-ed.

“The real big threat to the Zionist Project is not the ‘two state solution’ but rather the ‘one state solution’ which will lead inevitably to either a non Jewish or a non democratic, potentially ever bleeding State,” the passage, with its errors left intact, reads. “Still,this is the vision the Israeli extreme Right shares unknowingly with the Hamas (and with all due differences with the lunatic, Post Zionist fringes of the Israeli Left).”

Years later, Epstein shared a Tom Friedman column that similarly argued that Israel was now instead pursuing a “one-state solution,” which, among other things, was leading to a more uncertain future for the Middle East.

“Good summary,” Epstein commented.

This, besides his personal relationship with Barak, may explain Epstein’s claimed involvement in the 2019 Israeli election, reported by Jacobin earlier this week. Epstein had told Bannon shortly before his arrest that he had been behind Barak’s decision that year to come out of retirement and launch a challenge aimed at removing Netanyahu from power and putting in place a more liberal alternative — one that, incidentally, would have theoretically meant a return to an official policy of pursuing the two-state solution.

“China China China”

But the country that featured most heavily in Epstein’s private discussions contained in the files wasn’t Israel; it was China.

The subject of the United States’ chief geopolitical rival clearly loomed large for Epstein. Among the influential contacts he had collected was Robert Kuhn, an investment banker and intellectual whose overriding personal interest seemed to be in extracting funding from Epstein for a science docuseries he wanted to make, and he regularly plied Epstein with his China analysis before pivoting to talking about the project.

Another was billionaire hotel magnate Tom Pritzker, cousin of Illinois governor J. B. Pritzker, and executive chairman of the hawkish Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). The two regularly exchanged messages about meeting up, emails show, and in 2016, Pritzker sent Epstein a presentation at a meeting of the Aspen Institute, an annual gathering of largely hawkish national security establishment heavy-hitters.

Chat logs show Epstein repeatedly trying to get a skeptical Bannon to meet with Tom Pritzker.

“Can we use CSIS for anything? Tom has GREAT relations in China,” Epstein messaged Bannon in July 2018.

“Tom is totally sold out to China — CSIS carries,” Bannon replied.

“No space between yours and Tom’s view on China,” Epstein insisted.

It was in his private chats with the virulently anti-China Bannon that the country most often came up, with Epstein often framing China as a serious threat that had to be defeated. He relayed to Bannon in September 2018 that “my French govt guys” agreed with him “that China for the very first time is following an imperialistic strategy, well thought through. Covered in nice ‘silk.’” As evidence, he pointed to China’s entry into Iran, Venezuela (“brilliant move”), and “djubuti,” a characteristic Epstein misspelling of Djibouti, where China set up its first overseas military base in 2017 (“highly dangerous,” he told Bannon).

Epstein bounced between certainty that China was falling apart and warnings that it was a formidable foe. China is “a unified nationalist economic country” whose forty-year-long strategy is “right on track,” Epstein told Bannon in July 2018, relaying “intel” he had gotten; “they have manpower to marshall,” he wrote, and “don’t mind suffering to achieve their goals.” The country was “stronger, plays weakened,” was the opinion of his “China guys,” Epstein relayed to Bannon later that summer, alluding, not for the last time, to one of the lessons in The Art of War.

“They said China stronger today than when we started?” Bannon replied.

A few months later, Epstein gave him some slightly different intel. “I had three China guys today. I told them they should brief you,” he messaged Bannon that December. “Bottom line. Forcing china to turn ineard [sic] is counterproductive to containment. . . . It was decribed [sic] as both stronger but much more brittle.” A few hours later, he reiterated the point: “Brittle. Key.”

“Yes brittle key,” Bannon replied.

In one May 2019 exchange, Epstein sardonically chided Bannon for his insistence that the Trump administration would “break” China.

“They have North Korea, 3 trillion in reserves. People that work 29 hours per day. A command structure that is efficient. Not sure what breaking them means,” Epstein wrote.

“It’s a group of peasants trying to run a world economy — Xi barely has high school education, completely panicked when they read thru the deal — already leaking oil,” Bannon replied.

“My meeting the other day was around how these peasants looked into their own systems, found the NSA cybertools that we had inserted and then used them against us interests,” Epstein wrote back. “Ohh. Yes., I forgot. We have [then-Treasury secretary] Steve Mnuchin, and Ludlow,” he wrote, likely a misspelled reference to then-National Economic Council director Larry Kudlow.

The two men had a similar exchange days later, when Bannon insisted China would struggle in the face of a US-launched trade war. “I will simplify: they are looking down the barrel of an economic shotgun,” Bannon wrote.

“Yes but their finger is on the trigger. It is not simple at all,” Epstein replied.

Looking at the situation from the vantage point of 2025 — after a Trump-led trade war in earnest against the country rebounded disastrously on the United States, exposing its dependence on Chinese imports and forcing several embarrassing climbdowns from Washington as a result — Epstein looks like he had the better of the argument.

Nevertheless, one day later, Epstein was telling Bannon that China’s “slavery system is doomed,” pointing to its real estate bubble and what he viewed as its impending collapse. “They need to clean up their internal financial mess and will attempt to blame it on Trump,” he wrote. “It won’t work.”

Epstein told Bannon he agreed the United States was “at war” with China and had “been for years,” only fought with nontraditional weapons like technology and currency. But he also seemed to believe in encouraging that war.

“Your deplorables need an enemy,” he wrote in March 2019. “China China China.”

“Yes yes yes,” Bannon wrote back. “I’m the evangelicalist [sic] on this one.”

In one exchange earlier that month about Bannon’s appearance on Anderson Cooper’s CNN show, they strategized how to encourage such a war through the corporate press. “Turning him to your China side could be easier than one thinks. They need an enemy, China fits the bill,” Epstein told Bannon. “They need the new eyeballs. Big targets. Russia not useful, Trump dead for a while. Health care over. China perfect piñata.”

“Yes yes yes,” replied Bannon.

At the same time, Epstein repeatedly questioned Bannon’s preferred strategy of using trade (“a diversion that they love”) and tariffs (“a non event”) to take on China. “Ok, so if I understand, you want to win by knock out or tko,” he wrote to Bannon. “Their system is brittle. You guys should decide if trade a huge slow moving sledge hammer is the best way.”

Instead, he suggested the Trump administration would be more effective by looking at “attacking their propaganda,” and repeatedly urged him to “point out” or “call out China on currency” — in other words, to point out that China was artificially suppressing the value of its currency to give itself a trade advantage. He urged Bannon to pursue the “great opportunity” that India, with its similarly anti-China views and manufacturing potential, offered, and proposed to set up a meeting with far-right Indian prime minister Narendra Modi two months before he was arrested, noting that “his focus wants to be stopping China.” “Please,” replied Bannon.

Epstein’s views on China fit firmly into establishment thinking. On Russia, however, he took a different tack. “Trump is right in trying to bring them into a partnership,” Epstein told a delighted Bannon in July 2018. “Putin has been kind so far not to point out how the US involves itself in others elections, hasn’t pointed out assassinations to overthrow govts, coup funding,” he elaborated. “Russia a potential friend,” he told Bannon a year later.

The Man Behind the Curtain?

The latest disclosures about Epstein make the billionaire no less an enigmatic figure than before. They reveal a man who, in his conversations about foreign policy, contradicted himself, mirrored what the influential people he collected wanted to hear, and seemed to be driven by a variety of motives.

Yet arguably more important than why Epstein favored certain policies is what those policies actually were. More often than not, that meant a more hawkish posture toward US and Israeli adversaries, a posture that has often not served the United States or its people well. For those convinced Epstein was improperly influencing US foreign policy through his various activities, it should be a disturbing find.