The Forgotten History of Socialism and the Occult

Socialism has a well-earned reputation as a secular, rational movement. But not all socialists throughout history were quite so grounded.

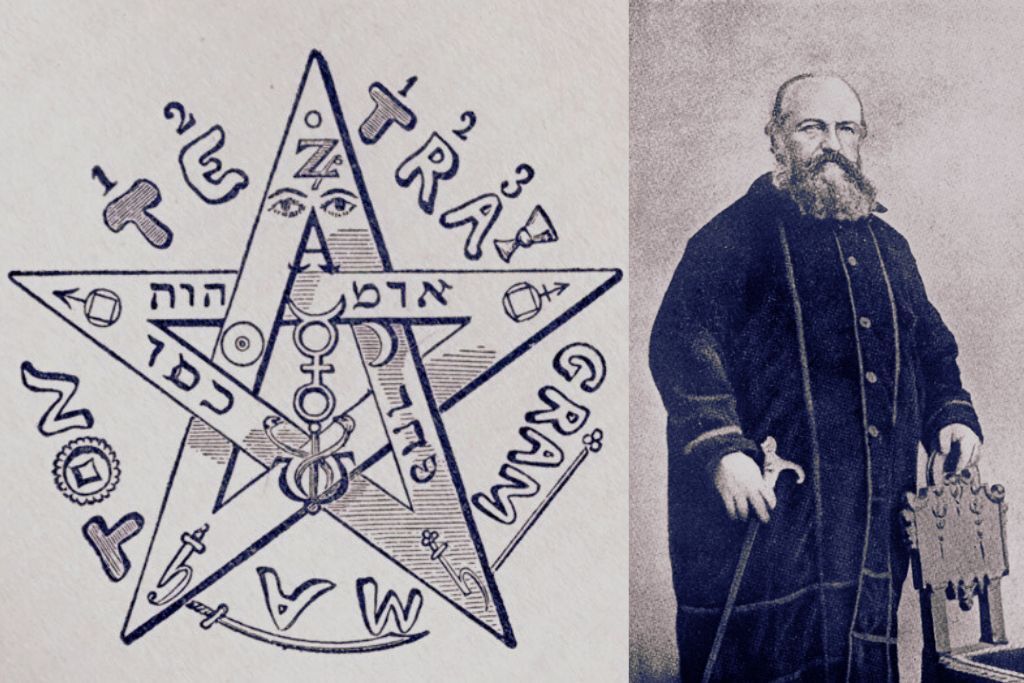

French occultist and socialist Eliphas Lévi and his pentagram design. (Project Gutenberg)

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels are the names that usually come to mind when people hear the word “socialism.” These two were not, however, the originators of socialism, but rather of a particular variant rooted in an objective analysis of economic conditions and class interests. They took great pains to distinguish their “materialist” socialism from the “utopian” socialism of their predecessors.

The utopians, Marx and Engels argued, lacked rigorous engagement with the actual productive forces and class antagonisms of their time. They were pseudo-religious and quasi-mystical, sounding more like prophets than scientists. They excitedly drafted blueprints for ideal cities, but “the more completely they were worked out in detail,” wrote Engels, “the more they could not avoid drifting off into pure phantasies.”

The materialists won the debate. When we talk about socialism now, we mostly refer to a tradition that draws on Marxist concepts: the proletariat, the bourgeoisie, class consciousness. Largely forgotten is the lexicon of, for example, the utopian Saint-Simonians: social regeneration, universal association, woman-messiah.

If today’s socialists know little about early socialist philosophies, they know even less about the fascinating relationship between utopian socialism and occultism. Non-Marxist socialist currents in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were closely intertwined with esoteric occult movements. Where one was found, the other was usually near at hand. Though we may be loath to admit it, socialist history featured more than a few séances amid the strikes.

The dialogue between socialism and occultism began in France in the early 1830s, when pre-Marxist socialists initiated a search for hidden knowledge and universal laws that they hoped would liberate humanity. It continued in the United States in the 1840s and 1850s, where utopian socialist communes served as refuges for spiritual seekers who fled traditional churches but retained their belief in supernatural phenomena and the divine revelation of hidden mysteries.

By the early 1870s, materialist socialism was making inroads in the American working class. The Knights of Labor had just been founded, marking the arrival of the trade union movement, and Marx’s class struggle–centric International Workingmen’s Association (IWA) was gaining traction. Oddly, one IWA local became helmed by an abolitionist, suffragette, and famous spiritual healer named Victoria Woodhull, who decided to run for president in 1872 under the group’s banner. Marx himself grumbled about Woodhull and her “middle-class” faction of “spiritists” whom he regarded as “swindlers” and “riff-raff” leading the movement astray.

How did a psychic medium end up embedded in a Marxist organization to begin with? We can only understand this episode by recognizing that, while the materialist ideology of the IWA was at this point worlds away from the esoteric theories of spiritualists, socialism and occultism occupied very tight quarters for many decades. Occasional run-ins of this sort would continue until the materialist parameters of the labor movement were officially established and the siren song of fascism beckoned occultists rightward. Up to that point, it was not uncommon to encounter dyed-in-the-wool socialists who dabbled in fortune-telling or attempted to make contact with the dead.

Socialism and French Occultism

In 1825, the year of his death, the French social reformer Henri de Saint-Simon published a book called Nouveau Christianisme (New Christianity). As esotericism and religion scholar Egil Asprem writes, Saint-Simon’s project was the “rejuvenation of Christianity by ridding it of corrupt priestcraft and establishing a progressive, ‘positive’ religion dedicated to the perfection and regeneration of humanity — here, on earth. Crucial to this task was the elevation of the poor.”

Adherents to Saint-Simon’s ideas were the first to be called “socialists.” But while socialism became axiomatically associated with secularism in later years, its passionate forerunners during France’s July Monarchy period were anything but. Religion scholar Julian Strube explains:

The Saint-Simonians and other socialists saw themselves struggling against a social fragmentation and “coldness” that had supposedly resulted from 18th-century atheism and materialism. In their eyes, those circumstances were responsible for the disruption of the social bonds, as they were the driving force behind the egoist “mercantilism” suffocating the lower classes.

The emergence of capitalism corresponded with a process of disenchantment that seemed to suck all the magic out of the world. The Saint-Simonians were, in protest and defiance of this icy alienation, interested in mounting a counteroffensive suffused with warm, romantic feeling. Strube reveals how overtly and intensely religious their movement was:

The Saint-Simonians saw themselves as the heralds of a new Golden Age that would overcome the social fragmentation and realize a harmonious unity of religion, science, and philosophy. They declared themselves a “church,” the église saint-simonienne . . . [and] regarded themselves not as the theoreticians of a politico-economic doctrine, but as “apostles” preaching the revelations of their “prophet,” Saint-Simon.

In 1848, two world-altering events happened: Marx and Engels debuted their materialist brand of socialism with the publication of The Communist Manifesto, and Europe erupted in a series of revolutions that dragged socialism into the realm of real, high-stakes politics. Thereafter, materialist socialism was on the rise and utopian socialism on the wane. But utopianism’s tail was long, having produced many ideas, thinkers, activists, and real-world experiments that would persist for decades.

It also produced another strain of thought altogether: occultism.

As Strube shows, occultism emerged in France not merely after utopianism but straight out of it. The widely regarded founder of occultism, Alphonse-Louis Constant, pen name Éliphas Lévi, was deeply involved in the pre-1848 Saint-Simonian socialist movement. Indeed, he debuted his ideas about Kabbalistic magic in a French socialist journal.

Constant’s first radical publication in 1841 had been La Bible de la liberté (The Bible of Liberty), which Strube describes as “an extravagant mixture of socialist, mystical, Romantic, and feminist ideas,” par for the course among Saint-Simonians at the time. In the 1850s, Constant, now writing under his pseudonym, published works including Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (Transcendental Magic), Histoire de la magie (History of Magic), and La clef des grands mystères (The Key to the Great Mysteries). These became the foundational texts of the esoteric movement, heavily influencing later occultists like Madame Helena Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley. Quite simply, the founder of occultism was a socialist.

Strube’s interrogation of Constant’s work finds no ruptural pivot: rather, his ideas flowed somewhat seamlessly between utopian socialism and eclectic esotericism, both of which concerned themselves with the pursuit of hidden universal laws that, once revealed, would liberate humanity. Marx and Engels found those laws in the dynamics of class struggle and the internal contradictions of capitalism; Éliphas Lévi found them in the secret correspondences between Hebrew letters and tarot cards, the androgynous Baphomet who reconciled all cosmic opposites, the astral light that recorded every human thought and action like a universal memory bank, and the conviction that Jesus Christ was actually an initiate of Egyptian mysteries who had discovered how to manipulate these invisible forces — all of which could be mastered through ritual magic to achieve nothing less than the regeneration of humanity and the establishment of a universal theocratic socialism ruled by initiated magi.

The relationship between non-Marxist socialism and esotericism persisted into the late nineteenth century. French esotericists continued to publish in socialist journals, where they also warned against the movement’s ambition and vitality being eroded by the “low politics” of the materialists. The materialists’ response to them, meanwhile, ranged from outright hostility and ridicule to a kind of amused curiosity tempered by comradely advice to focus on practical matters.

When the most influential esotericist organization of the late nineteenth century, the Theosophical Society, founded its first chapter in France called the Isis Lodge, it held its inaugural meeting in the offices of the Revue socialiste — an ecumenical socialist journal that also published Engels’s famous broadside against the utopians. The Isis Lodge was founded in 1887 by Louis Dramard, who had previously written an article in the Revue exhorting fellow socialists to recognize “the intrinsic value of occultism.”

Dramard died shortly thereafter in the Maghreb fighting for the rights of Algerian workers. He died every bit as much a socialist as an esotericist. He was hardly singular. As embarrassing as it may have been for the materialists of the era, there were plenty of earnest socialists who believed a better world lay beyond capitalism — and that uncovering the hidden laws that bind humanity and cosmos would hasten its arrival.

Socialism and American Spiritualism

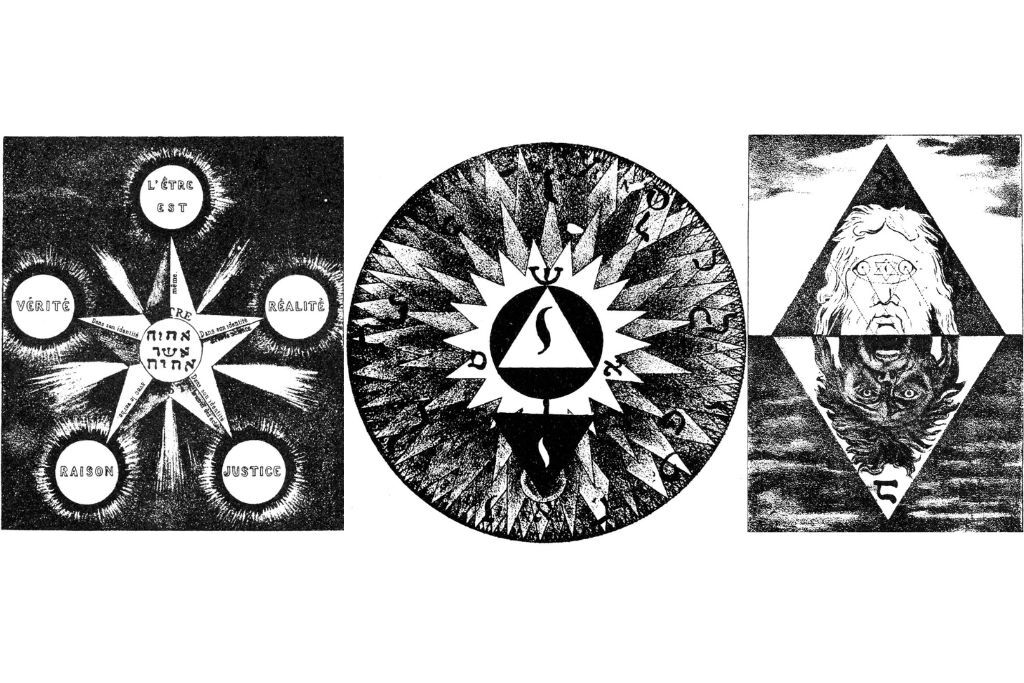

Across the Atlantic, it was not Saint-Simon whose followers blended occultism and socialism but his contemporaries, the French utopian Charles Fourier and his Welsh counterpart, Robert Owen. The two were directly and indirectly responsible for the creation of dozens of communes, many of which doubled as centers of spiritualist experimentation.

Owen came to an esoteric belief system called “spiritualism” only in his eighties, having long embraced a more secular utopian socialism that emphasized planned egalitarian communities. In the final years of his life, he “saw spiritualism as a natural extension of his cooperative principles — a belief in the interconnectedness of all beings, transcending the physical plane.”

But his was not a life full of crystal balls and Ouija boards. In addition to his interest in cooperativism, Owen was heavily involved in the early British labor movement and the precursors to trade unions. Marx spoke approvingly of Owen on many occasions.

Though Fourier’s philosophy was far more idiosyncratic than Owen’s, in the typical French style of the period, neither was he an occultist. His primary belief was that humans, alienated from their labor, could organize society in a more rational way that would promote harmony, equality, fraternity, and pleasure in work and leisure alike. To that end, he proposed the creation of “phalanxes,” or communal societies, organized around key rational principles.

Nevertheless, Fourier did take it upon himself to blend science and religion in pursuit of a grand “theory of universal harmonies.” Beyond the basic tenets of his thought, one finds in Fourier’s writings many whimsical flourishes, like his enumeration of “the twelve passions” driving humanity and his detailed taxonomy of personality types.

Fourier’s French adherents wasted no time, even during his life, making a quasi-religion out of his philosophies and interpreting them in esoteric ways. As early as 1832, his follower Just Muiron was claiming that Fourier’s ideas were in sync with those of figures like Franz Mesmer, a trance healer (from whom we derive the term “mesmerize”), and Emanuel Swedenborg, a Christian mystic who promoted a cosmology of multiple heavens and hells corresponding to spiritual states. Fourierists would debate the proper place of spirituality in their ideology for decades, with internal critics accusing the esotericists of “blasphemy to logical progress.”

In the United States, where real-world Fourierist and Owenite experiments abounded, several factors converged to proliferate esoteric beliefs and practices. The first was the rising number of post-Christian spiritual seekers, usually Protestants who had left their traditional churches but had not embraced thoroughgoing secularism, leaving them wandering in pursuit of a replacement. Many were attracted to the ideas of the aforementioned Swedenborg; one Fourierist commune in Massachusetts, Brook Farm, was replete with Swedenborgians. For these commune-dwellers, egalitarian social experimentation and spiritual syncretism were part of the same grandiose millenarian project.

The second critical influence was the growth of American spiritualism, the same belief system that counted Owen as a late-in-life convert. Spiritualism was born in 1848 — the same year as the European revolutions and the publication of The Communist Manifesto — when the Fox sisters of upstate New York claimed to communicate with spirits through mysterious rappings, sparking a movement that spread rapidly across the United States. The movement found particularly fertile ground among progressive reformers, as spiritualist circles became venues where women could speak publicly as mediums and assert spiritual authority in an era that otherwise denied them political and religious leadership.

Many prominent suffragists and abolitionists, including Susan B. Anthony and Sojourner Truth, participated in spiritualist activities, viewing communication with the dead as compatible with their campaigns for earthly justice. One abolitionist spiritualist recorded a supposed conversation he had with the ghost of an enslaver this way:

Qu – Do not the colored and the white races associate in the spirit world?

Ans – They are all there and can associate if they wish.

Qu – Are you in anywise disquieted in consideration of your having held slaves in life?

Ans – I do not believe as I used to, but I always treated them kindly, and that is a happy thought. Good night Reverend Pierpoint.

The overlap was so pronounced that anyone interested in socialism during this period would have inevitably encountered spiritualist ideas, as the same lecture halls, newspapers, and social networks that promoted cooperative economics also hosted séances, trance speeches, and debates about the spirit world’s endorsement of social reform. In this radical milieu, the boundaries between political organizing and spiritual experimentation were remarkably porous, with reformers moving fluidly between discussions of labor rights, women’s equality, racial justice, and messages from the beyond.

Brook Farm, the Massachusetts commune populated by Swedenborgians, only existed for six years, from 1841 to 1847, but in that short time the community experimented with séances, table-turning, and a practice called psychometrics, which involved divining information from talismanic objects. At one séance, writes Edmund Berger in Cosmonaut, a resident practicing psychometry “encountered the spirit of Fourier himself and reportedly carried out a conversation with him.”

Brook Farm was far from the only place where utopian socialism and American spiritualism were colliding. In Yellow Springs, Ohio, for example, a couple who was married in a Swedenborgian ceremony established an intentional community that was dedicated to hydropathy, a movement of spiritual “water cures.” As Berger points out, the couple opened the Memnonia Institute, as it was called, on Fourier’s birthday. Also in Ohio, Berger notes, a visitor to a commune called the Prairie Home Community was surprised to hear residents, engaged in the hard work of their chores, “converse so freely upon Phrenology, Physiology, Magnetism, Hydropathy,” and the like.

Across the country, Fourierist and Owenite communes dabbled in the American variant of esotericism. These utopian socialists were on a journey to discover radical alternatives and reveal ultimate truths that might help humanity live more freely and harmoniously, and they did not restrict their epic search to the earthly realm. Materialist socialism was also taking root, but despite their wildly different orientations, the two traditions were not yet occupying completely separate social and intellectual milieus. Rationalist forces dedicated to advancing class struggle were amassing — but even the working-class Knights of Labor had a decidedly occult ring to their name, inspired as they were by secret societies like the Freemasons.

Materialist socialists may be uneasy with this irrational, anti-modern strain in our movement’s history, but facts are facts. For several decades in American socialist history, certain self-identified socialists were more likely to hand you a book by Andrew Jackson Davis, a famous clairvoyant and spiritualist author also known as the “Poughkeepsie seer,” than a copy of The Communist Manifesto.

Exorcism by Marxism

In the decades that followed, the United States and Europe saw several more convergences of socialism and occultism. For instance, when the socialist Edward Bellamy published his wildly popular utopian socialist novel, Looking Backward, in 1887, it inspired a new flurry of utopian socialist activity. Bellamy clubs were established across the nation, many chartered by none other than the aforementioned esotericist Theosophical Society.

“Just as spiritualism and Fourierism were intertwined,” writes religion scholar Dan McKanan, so the Bellamyite socialists “built on the organizational structures of Theosophy, a partial successor to spiritualism that relied on the revelations of mysterious ‘Mahatmas’ rather than of dead spirits for its cosmology.” Theosophy was by now fully immersing itself in eastern esoteric concepts, hence the “Mahatmas.” But it had not yet relinquished its hold on the remnants of utopian socialism.

In time, however, Marxism’s growing hegemony lent socialism a distinctly materialist and secularist flavor, and the pairing became increasingly difficult to justify. When utopian socialism died out, occultism was left politically adrift. But not for long: European and American fascists were growing increasingly interested in the ideas of Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society.

Certain preoccupations of Blavatsky’s, including her theories of “root races” and the spiritual evolution of humanity through distinct racial stages, seemed to justify the hierarchies central to fascist ideology. Indeed, the Nazis’ use of the swastika owed to the Theosophical Society’s popularization of that eastern symbol in occult circles. Likewise, the Nazis’ use of the term “Aryan” is a reference to an ancient race that Blavatsky claimed was spiritually superior and destined to lead human evolution.

Occultism has long since lost serious purchase among socialists, thankfully, only occasionally making rare appearances on the non-materialist left. Examples of its resurfacing range from the apocalyptic, like Jim Jones’s commune-turned-death-cult Peoples Temple, to the anodyne, like some progressive leftists’ penchant for astrology. But there’s no question that esotericism is far more at home today on the far right.

Nazi and neo-Nazi movements have routinely drawn on Nordic paganism, runic symbolism, and völkisch mysticism to construct their ideological foundations. From the occultist Thule Society’s influence on early Nazism to contemporary groups like the Odinists and Wotanists, the far right has consistently elevated pre-Christian Germanic spirituality (or their eclectic recreations of it) as a supposed alternative to “foreign” Abrahamic religions.

The esoteric strain in modern fascism comes and goes in cycles, and it seems to be waxing again. Today’s far-right violent extremists are indebted less to the Turner Diaries than to James Mason’s Siege, an eclectic mix of Satanism, sadism, nihilist accelerationism, and fascist loathing of supposed social inferiors. Occultism is right-coded in other ways too. Of particular interest is the emergence of esoteric themes on the tech right, from adherents of the cybernetic Kabbalist philosopher Nick Land to “technopagans” and alleged “Aleister Crowley cults” in Silicon Valley.

Occultism may have emerged from utopian socialism, but so, too, did Marxist materialism. Where the latter flourished, the former stood no chance at survival. A parable to illustrate the principle: Upon his release from prison in 1967, America’s most famous self-styled esoteric prophet and cult leader, Charles Manson, tried to recruit followers on Telegraph Avenue, a countercultural hotspot in Berkeley, California. There, he met with limited success. The explicitly socialist Free Speech Movement was fresh on everyone’s minds, and the street boasted not one but two Marxist bookstores. So Manson crossed the bay to try his luck with the hippies in the Haight-Ashbury district, which was essentially a giant ad hoc commune during the Summer of Love. His prospects improved, and the Manson Family was born.

There may be some wisdom in the early utopian socialists’ esotericism — particularly their observations about the coldness of capitalism and the need for a certain humanistic warmth in anti-capitalist resistance. Nevertheless, materialist politics have also functioned as a necessary prophylactic, encouraging political productivity by keeping socialists focused on earthly dynamics and battles to be fought in this world. Our movement is better off for esotericism’s drift rightward; the Right is welcome to distract itself with necromancy while we engage in rational political and economic analysis to strengthen the workers’ movement. The history of socialism and the occult suggests that Marxism is an effective exorcism.